IF-IHC Panel Discussion on ‘Indian Perspective on Myanmar Elections and Its Aftermath’

On 13th October 2025, India Foundation in collaboration with India Habitat Centre organised a panel discussion on ‘Indian Perspective on Myanmar Elections and Its Aftermath’. The panel consisted of Shri. Rajinder Khanna, Former Additional National Security Advisor; Ms. Rami Niranjan Desai, Distinguished Fellow, India Foundation; Shri Om Prakash Das, Research Fellow, MP-IDSA; Shri Rajiv Bhatia, Former Ambassador of India to Myanmar and Distinguished Fellow, Gateway House.

The session was moderated by Shri Alok Bansal, Executive Vice President, India Foundation, who in his address highlighted that “elections possess the transformative potential to usher in prospects of peace and development.” He further noted that in today’s interconnected world, media and technology enable a two-way flow of communication, which should form the foundation of constructive engagement and progress in the region. Shri Bansal also observed that Myanmar’s governance and territorial control have long been influenced by various armed organisations, making the country’s political transition particularly complex and multifaceted.

The speakers shared nuanced perspectives on Myanmar’s internal dynamics, the conduct of the elections, and the subsequent political developments. Speakers discussed the continuing influence of the military, the challenges of restoring democratic governance, and humanitarian concerns arising from internal displacement and conflict. The discussion underscored that the situation in Myanmar remains fluid and deeply consequential for the broader South and Southeast Asian region. While the elections were expected to serve as a step towards democratic consolidation, the ensuing political fragmentation has revealed the fragility of the country’s institutions and the entrenched role of the military and armed organisations in governance.

From an Indian perspective, the discussion underscored the delicate balance that the government must maintain- upholding democratic values while safeguarding its strategic and security interests. Experts highlighted the importance of continued engagement with Myanmar’s various stakeholders. Discussants also reflected on the responses of ASEAN and other international actors, analysing the impact of geopolitical competition in the Indo-Pacific on Myanmar’s trajectory. The session reaffirmed that Myanmar’s path to peace and democracy will be long and uncertain, but continued engagements offers the best hope for positive transformation.

Upon completion of the discussion, a report titled ‘Myanmar: A Struggle for Stability,’ based on Ms Rami Niranjan Desai’s expertise and fieldwork, which incorporated visits to different parts of Myanmar was released. Link of the Report:

https://indiafoundation.in/category/report/

9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference, Ahmedabad, 18–20 September 2025

The 9th International Dharma-Dhamma Conference, jointly organised by India Foundation and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahmedabad, was inaugurated on 18 September 2025 at the University campus. With the theme “Karma, Reincarnation, Transmigration, and the Avatar Doctrine”, the three-day conference brought together over 200 scholars, spiritual leaders, and policymakers from sixteen countries that includes Armenia, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, France, Georgia, India, Japan, Mauritius, Myanmar, Nepal, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam. The conference reaffirmed its position as a premier global platform for dialogue between Hindu and Buddhist traditions, aimed at fostering harmony, interconnectedness, and a shared philosophical framework for the emerging world order.

The inaugural session was graced by eminent dignitaries including Shri Acharya Devvrat, Hon’ble Governor of Gujarat; Shri Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, Hon’ble Union Minister of Culture and Tourism, Government of India; H.E. Mahendra Gondeea, OSK, Minister of Arts and Culture, Mauritius; H.E. Tshering, Minister of Home Affairs, Royal Government of Bhutan; Swami Govinda Dev Giri Ji Maharaj, Treasurer, Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust and Prof. Dr. Ami Upadhyay, Vice Chancellor, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University.

Over the course of three days, a total of 91 research papers were presented across 15 parallel sessions, constituting a significant part of the 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference. Jointly convened by India Foundation and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, this segment provided a rigorous academic platform for scholars, researchers, and practitioners to share innovative perspectives on the overarching theme “Karma, Reincarnation, Transmigration and The Avatar Doctrine.”

Inaugural Session:

The inaugural session of the 9th International Dharma-Dhamma Conference began with an inspiring address by Swami Govinda Dev Giri Ji Maharaj, Treasurer, Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust. Welcoming the gathering on behalf of India Foundation and as the Chair of the organising committee of the 9th DDC 2025, he spoke of India as the cradle of spiritual traditions including Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Emphasizing that the foundation of Indian thought is Dharma, he noted, “Our ancestors have taught us non-aggression and moral elevation, with the eternal motto: Sarve Bhavantu Sukhinah — may all be happy. Differences may exist here and there, but the sameness of our values is far greater.” He urged participants to strengthen the ties of brotherhood, focus on unity rather than differences, and collectively face the challenges confronting humanity.

H.E. Tshering, Minister of Home Affairs, Royal Government of Bhutan, extended warm appreciation to the hosts for convening the timely dialogue. He reflected on the need to reaffirm Dharma in a world dominated by materialism and secular thought: “Dharma is the timeless source of peace, harmony, and happiness. Both Hinduism and Buddhism remind us that life is interconnected, that we are bound together in a shared destiny.” He explained how the Buddhist principle of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination) underscores this interdependence, linking karma, reincarnation, and transmigration to a shared reality of existence. Citing contemporary challenges like climate change, inequality, and polarization, he stressed the urgent need for compassion and collective action. Concluding, he invited delegates to Bhutan’s forthcoming Global Peace Prayer Festival in November 2025, framing it as a continuation of the eternal cycle of Dharma.

From Mauritius, H.E. Mahendra Gondeea, OSK, Minister of Arts and Culture, situated his country’s cultural experience within the spirit of Dharma. He remarked, “Mauritius is a living testament to the enduring relevance of Dharma in the modern world. Our multicultural society thrives on tolerance, dialogue, and respect — values deeply rooted in Dharma traditions.” Drawing on the conference theme, he underlined how karma and reincarnation can serve as guiding principles for reconciliation, non-violent diplomacy, and environmental responsibility. He noted that peace is not simply the absence of conflict but the presence of justice and shared prosperity. Recalling the words of Mahatma Gandhi — “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others” — he urged the gathering to build a new world order anchored in Dharma, compassion, and sustainability.

Delivering his address, Shri Gajendra Singh Shekhawat, Hon’ble Union Minister of Culture and Tourism, Government of India, posed profound questions on human existence, noting that civilizations flourish not by power alone but by their capacity to engage with philosophy and truth. He clarified that karma is not fatalistic destiny but the architecture of responsibility, while reincarnation teaches humility and interconnectedness. Highlighting the avatar doctrine, he explained, “When Dharma declines, the moral order renews itself through reformers, saints, and great movements. This doctrine is not just about divine descent, but about hope — a reminder that compassion reappears when the world needs it most.” He called for the application of ancient wisdom to modern challenges, from climate change to cultural diplomacy, and reaffirmed India’s commitment to preserving and sharing its spiritual heritage globally.

Shri Acharya Devvrat, Hon’ble Governor of Gujarat, in his address congratulated the organizers and emphasized that philosophy defines the true purpose of life. He highlighted the Vedas as the world’s oldest repository of knowledge and recalled the eternal dictum Dharmo Rakṣati Rakṣitaḥ, noting that Dharma alone sustains the balance between violence and non-violence, Dharma and Adharma, and guides humanity toward righteousness. Invoking Maharshi Dayanand Saraswati, he underlined the importance of the doctrine of rebirth in understanding the continuity of life and Dharma. He stressed that Dharma was created to guide human conduct in every aspect of life and explained that practical living according to Dharma means not lying if we do not want others to lie to us and not looking at another’s sister or daughter with ill intent if we expect the same for our own. He further noted that the opposite of non-violence is violence, and the opposite of truth is falsehood; when these are applied to society, whatever sustains it is Dharma, and what fails to do so is Adharma, asking rhetorically whether society could survive even a single day on falsehood.

Benedictory Session:

The benedictory session of the 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference was chaired by Mr. Come Carpentier, Distinguished Fellow, India Foundation and Co-Chair of the 9th DDC 2025, who opened the dialogue with profound reflections on the eternity of the universe. Drawing parallels with the Kalpavriksha and the Bodhi Tree, he reminded the audience that the law of karma remains central to the functioning of existence. He noted that even modern scientific explorations, including quantum physics, continue to echo these timeless insights, reaffirming how ancient wisdom remains aligned with contemporary understanding of the cosmos.

Swami Govinda Dev Giri Ji Maharaj, Treasurer, Shri Ram Janmabhoomi Teerth Kshetra Trust, India, reflected on karma as noble action that underpins life across Vedic, Jain, and Buddhist traditions. He explained the Vedic classification of karma and stressed the need for balance in life, quoting the prayer “Asato Ma Sadgamaya, Tamaso Ma Jyotirgamaya.” Speaking on the doctrine of avatars, he emphasized that incarnations arise whenever moral equilibrium falters, with their purpose being the restoration of righteousness and harmony in society.

From Thailand, Most Venerable Arayawangso, Chief Abbot of Buddhapojhariphunchai Forest Monastery (D) under Royal Patronage of HRH Princess Bajrakitiyabha Narendira Debyavati, the Princess Rajasarini Siribajra Mahavajrarajadhita, spoke of Dhamma as natural law, encompassing the laws of action, biology, and physics. Drawing from Buddha’s enlightenment, he explained central Buddhist concepts such as mano kamma (mental action), idapaccayata(conditionality), and paticcasamuppada (dependent origination), highlighting the interconnectedness of existence. Reaffirming the Four Noble Truths, he underscored the enduring relevance of Dhamma as the guiding principle of wisdom and liberation.

Mahamahopadhyaya Swami Bhadreshdas, Head, BAPS Swaminarayan Research Institute, Akshardham, New Delhi, described the conference theme as addressing the mystery of the entire universe. He emphasized that the pursuit of moksha illustrates the depth of Indian philosophical thought. Reflecting on the eternal struggle between dharma and adharma and the varied types of karma, he stressed that sincere fulfillment of one’s kartavya (duty) leaves an enduring legacy. Citing the story of Nachiketa and principles of the Bhagavad Gita, he affirmed that righteous action and spirituality form the bedrock of Dharma’s continuity.

Concluding the Benedictory session, Bhaddanta Kovida, Aggamahapandita, Aggamahasaddhammajotikadhaja, Vice Chairman of the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, Myanmar, offered his blessings. He affirmed the relevance of Dhamma as a universal guide for humanity, emphasizing its role in fostering peace, compassion, and harmony in an interconnected world.

The benedictory session thus captured the spirit of the conference, bringing together diverse traditions in a collective affirmation of Dharma and Dhamma as eternal pathways for balance, wisdom, and global harmony.

2nd S. R. Bhatt Memorial Lecture – 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference:

Dedicated to the memory of the eminent philosopher Late Prof. S. R. Bhatt, the second S. R. Bhatt Memorial Lecture at the 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference celebrated his lasting contributions to Indian philosophy and intercultural dialogue. The session provided an opportunity to reflect upon his vision of philosophy as a bridge between civilizations and a guide to spiritual awakening.

The session was chaired by Dr. Sanjay Paswan, Former Minister of State, India, who emphasized that self-discovery is realized through Dharma and spirituality, while yoga offers a vital path to stress reduction and inner balance. He reflected that every religious tradition begins as an idea, evolves into a belief, and ultimately matures into a philosophy. Citing India’s rich philosophical heritage, he noted how its scriptures and traditions have illuminated the global understanding of spirituality. He further remarked that the Dharma Dhamma Conference, as an international platform, enables diverse philosophical perspectives to converge, reinforcing that philosophy is the path to awakening the consciousness of the mind.

The memorial lecture was delivered by Prof. Geo Lyong Lee, Former President of the Korean Society for Indian Studies, South Korea, who began with a poem dedicated to Prof. S. R. Bhatt. In his address, he explored the profound influence of Ramanujacharya’s Vishishtadvaita Vedanta while drawing insightful comparisons between Shankaracharya’s Advaita Vedanta and Korean philosophical traditions, underlining their shared dimensions. He reflected on the philosophical inquiry into the origin of the universe and stressed that, in the present era, humanity’s foremost goal must be peace. He also highlighted Korea’s historical role as a significant center of Buddhism, illustrating the deep spiritual ties across civilizations.

The session concluded with a vote of thanks by Dr. Rajiv Bhatt, son of Late Prof. S. R. Bhatt, who expressed heartfelt gratitude to the speakers, dignitaries, organizers, and participants for honoring the memory of his father and contributing to the success of the memorial lecture.

Plenary Session 1 –Day 2

Chaired by Prof. Sunaina Singh, Former Vice-Chancellor, Nalanda University, the session underlined the importance of comparative reflection: Prof. Singh recalled the widespread presence of transmigration doctrines—from Vedic and Buddhist thought to Pythagoras and Platonic currents—and urged participants to situate the conference’s debates within long genealogies of thought while exploring shared parameters across traditions.

Swami Mitrananda, Spiritual Teacher, Chinmaya Mission, stressed the centrality of spiritual discipline and the graded methods of sadhana that accommodate seekers at different stages. He outlined four pragmatic stages of inner evolution—from outwardly driven action to dedicated japa practice and, ultimately, to steady meditation—and argued that if formal meditation proves difficult one may begin by dedicating all actions to the Divine or practising detached action (karma-phala vairagya). His exposition highlighted the inclusivity of Indian spiritual systems, which prescribe different practices for different temperaments and thereby make inner transformation widely accessible.

Dr. Supachai Veerapuchong, Secretary-General, BodhiGayāVijālaya 980 Institute, Thailand, described his institute’s applied work—Dhamma Yatras, SAMVAD talks and community projects—and opened with a short documentary showcasing those initiatives. He argued that the true “motherland” is where Dharma is embodied, not merely studied, and emphasised simple ethical injunctions (rooted in the five precepts) and mindful breathing as practical tools to control emotion, reduce suffering and make spiritual teachings lived realities. Drawing on personal testimony, he urged leaders to first listen, then reflect, and finally implement Dharma’s principles in public life.

Mr. Maris Sangiampongsa, Former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Thailand, traced the institutional history behind regional Dharma initiatives and reflected on his own ordination and transformation. He described how ordinary professionals—business people, civil servants and ministers—have been renewed through disciplined practice, and he presented the institute’s mission to translate Buddhist principles into everyday business ethics and collaborative models. Emphasising Asia’s centrality in the twenty-first century, he advocated applying Dhamma to foster cooperation rather than competition among nations and enterprises.

Prof. Il Soo Moon, Director, International Sati Institute; Emeritus Professor, Dongguk University College of Medicine, South Korea, introduced a neuroscientific reading of Buddhist psychology, framing mind-space as a subjectively constructed virtual field that arises during perception. Drawing on concepts such as anusati(recollection/memory image) and classical accounts in the Saṃyutta Nikāya, he explained how perceptual influxes shape mental representations and how disciplined practice can modulate these processes—thereby linking ancient doctrinal categories to contemporary cognitive neuroscience.

Plenary Session 2 – Day 2

Prof. (Dr.) Ami Upadhyay, Vice Chancellor, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Open University, Gujarat, reflected on the deep connection between Dr. B. R. Ambedkar and Buddhism, linking the Dashavatara tradition, karma, and classical dance as a medium of spiritual and cultural expression. Quoting “Yatho manah thatho bhava” (as is the mind, so is the becoming), she emphasized the importance of mindfulness in one’s actions and explained how karma makes the journey of life continuous, mirrored in the cycle of birth and rebirth.

Ms. Veena Upadhya, Assistant Secretary-General for Foreign Affairs, BodhiGayāVijālaya 980 Institute, Thailand, spoke on the role of karma and reincarnation in shaping human destiny, noting how Buddha’s visions of past lives and his conscious decision to teach highlight the inescapability of karma. Drawing on the Upanishads and Buddhist teachings, she underlined the importance of awareness, good actions, and the Eightfold Path, stressing that true peace lies within and that purification of the mind transforms life and community.

Dr. Karl-Stéphan Bouthillette, Professor, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, examined karma as both problem and paradox, arguing that in Jainism and Buddhism it was not a guarantee of cosmic justice but a mechanism binding beings to saṁsāra. He described renunciation as “ascetic resistance”—a refusal to participate in the karmic economy of worldly life. While acknowledging modern reinterpretations of karma as activism and ecological care, he warned that celebrating action may reinforce the very cycle traditions sought to escape, urging detachment, clarity, and a recognition that samsara “was never great and cannot be repaired.”

Tulku Tenzin Gyurmey Rinpoche, Founder, Thubten Shedrubling Foundation (TSF), Tawang, offered an in-depth explanation of the Tulku system in Tibetan Buddhism, grounding it in the Mahayana ideal of bodhisattvas returning to the world out of compassion. He outlined the history of reincarnation in Tibet, beginning with the Karmapa in the 12th century, and explained why High Lamas reincarnate—through karmic connections, prayers of compassion, and disciples’ requests. He detailed the rigorous procedures for identifying reincarnations, including signs, tests, and oracles, and emphasized that the system is rooted in both philosophy and devotion.

Dr. Lobsang Sangay, Senior Visiting Fellow, East Asian Legal Studies Program, Harvard Law School; and Former Sikyong (President) of the Central Tibetan Administration, spoke candidly about India’s place in history and the present. He contrasted the concept of karma with contemporary global crises such as wars, authoritarianism, and refugee flows, questioning why self-correction seems absent. He highlighted India’s ancient role as a center of knowledge and Buddhist diplomacy under Ashoka, and urged investment in infrastructure, institutions like Nalanda, and Buddhist cultural diplomacy. Warning that China has outpaced India in Buddhist soft power, he called for revival of India’s heritage to regain leadership in the global spiritual and cultural sphere.

Plenary Session 3 – Day 3

The third plenary session of the 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference deepened the exploration of the theme “Karma, Reincarnation, Transmigration and The Avatar Doctrine” by weaving together perspectives from philosophy, science, and Buddhist studies.

Dr. Satyapal Singh, Former Chancellor, Gurukul Kangri University, Haridwar, and Former Union Minister of State, India, chaired the session. He emphasized that the theme of the conference touches the very essence of life, observing that the true path to happiness lies in Dharma. Quoting Dharmo rakṣati rakṣitaḥ (Dharma protects those who uphold it), he underlined that Dharma and Dhamma are universal, transcending boundaries of faith or culture. He also drew attention to the idea of cosmic consciousness and reflected that the roots of the Vedas are, in essence, the roots of science.

Prof. Takahiro Kato, Professor, Department of Indian Philosophy and Buddhist Studies, University of Tokyo, Japan, examined the relationship between karma, determinism, and moral responsibility. He explained how Indian traditions conceptualize karma not only as individual action but also as a shared responsibility, drawing on Mīmāṁsā’s principle of beneficiary designation and Buddhist practices of merit dedication. Citing the Mahābhārata, he reflected on how Indian thought reconciles determinism with freedom, presenting a nuanced form of compatibilism in which actions are conditioned by the past but remain open to ethical choice in the present.

Dr. Anirban Bandyopadhyay, Senior Scientist, National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS), Tsukuba, Japan, brought a scientific and personal dimension to the discussion. Recalling the experience of witnessing death in his family, he connected his reflections to avatāra and reincarnation through the lens of Sāṅkhya philosophy and the debates of Maharshi Kapil. He introduced the framework of Kālacakra, describing it as the rhythm of time, existence, and consciousness, and linked these insights to modern medical science, where bodily vibrations and energy flows are central to understanding life. By presenting Kālacakra as a shared language between philosophy and science, he offered a bridge between ancient traditions and contemporary knowledge systems.

Prof. Saswati Mutsuddy, Professor and Head, Department of Pali, University of Calcutta, India, emphasized that karma forms the very foundation of existence in Buddhism, governed by the universal law of cause and effect. Quoting the Buddha’s injunction Appadīpo Bhavah (be a light unto yourself), she highlighted the importance of self-reliance and inner strength. She explained how the Pañchaśīla (Five Precepts) and the role of chetanā (intention) guide ethical action, and stressed that no karma is without consequence. She further reflected on samādhi as the active discipline of the mind, clarifying that calmness is not passivity but cultivated clarity and strength, vital for understanding reality and moving toward liberation.

Plenary Session 4 – Day 3

The fourth plenary session of the 9th International Dharma Dhamma Conference continued the dialogue on “Karma, Reincarnation, Transmigration and The Avatar Doctrine”, highlighting philosophical, cultural, and psycho-spiritual perspectives.

Prof. Ramesh Chandra Sinha, National Fellow, Indian Institute of Advanced Study (IIAS), Shimla, India, chaired the session. He emphasized the profound significance of the central theme and reflected on the depth of the concept of karma and the broader karma theory. He noted that the study of karma transcends a single tradition, representing a meaningful fusion of cultures and serving as a bridge for dialogue and understanding between diverse philosophical heritages.

Prof. Jagbir Singh, Chancellor, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, India, highlighted the deep connection between Sanatan Dharma and the Sikh tradition. He observed that while Sanatan Dharma represents the ancient, the Sikh parampara reflects the new, yet both share the same cultural and spiritual continuum. Citing scholars such as Max Arthur Macauliffe, he discussed the enduring vibrancy of Sikh civilization, the unbroken lineage of knowledge (jñāna parampara), and the teachings of Guru Nanak Ji. He referred to the Ṛgveda’s eternal truth, “Ādi Sach, Jugādi Sach,” connecting it to Vedic concepts of Om and Brahman as the ultimate reality (Satyam Jñānam Anantam Brahma), and reflected on the relationship between the individual soul and the supreme Brahman.

Mr. Kim Jongwoo (Bhikshu Dowoong), Korea Sanskrita Shiksha Sansthanam (KSSS), South Korea, discussed the role of scripts and languages in preserving and transmitting cultural and spiritual heritage. He highlighted the historical significance of Devanagari and Brahmi scripts in Buddha Dharma and emphasized the meticulous rules guiding sacred text translation across regions. He also reflected on Buddhist art and sculptures as carriers of Dharma. Drawing parallels to Korea, he described the creation of the Hangul script, woodblock mantras, and the architectural and spiritual significance of Korean Buddhist temples, underscoring the deep interconnections between language, art, and living Buddhist tradition.

Mr. Ashwani Kumar, Founder of Happy Life University and psycho-spiritual expert, presented a consciousness-centered perspective on karma and energy. He emphasized that all beings are constantly in action, but the nature of karma varies across life forms—guided by instinct in animals, and by both instinct and intellect in humans. Highlighting the human tendency to be ensnared by the illusions of maya, he explained that true karma is measured by conscious alignment with dharma and divine will rather than mere outcomes. He outlined the soul’s journey through reincarnation and transmigration and illustrated the concept with the analogy of a spiritual GPS, termed God’s Guidance System (GGS), which directs the soul toward its ultimate cosmic purpose.

Dr. Ram Madhav, President, India Foundation, delivered the concluding remarks, reflecting on the intricate interplay between the theme of the conference and consciousness and emphasizing that individual perception significantly shapes the realization of future outcomes. He highlighted the importance of empirical research to further deepen understanding in these domains and underscored the ongoing need for rigorous scholarly inquiry into the principles of Dharma and Dhamma.

IF-IHC Book Discussion on ‘Trial by Water: Indus Basin and India-Pakistan Relations’, by Shri Uttam Kumar Sinha

India Foundation, in collaboration with the India Habitat Centre, organised a book discussion on the book ‘Trial by Water: Indus Basin and India-Pakistan Relations’, by Shri Uttam Kumar Sinha, Author and Scholar, on Monday, September 22, 2025, at India Habitat Centre. Dr. DV Thareja, Former Indus Water Commissioner and Former Member (D&R), CWC; Dr. Tara Kartha, Director (R&A), CLAWS; and Amb. Sharath Sabharwal, Former High Commissioner of India to Pakistan, discussed the book with the author. The session was moderated by Capt. Alok Bansal, Executive Vice President, India Foundation.

Shri Uttam Kumar Sinha clarified that the treaty was not solely about water sharing but involved a complex division of river systems, with an 80/20 water allocation split, often perceived as unfair by both nations. He addressed misconceptions about the treaty, emphasizing Nehru’s intent to foster peace, contrasted by opposing motivations from other stakeholders. Shri Sinha noted the pivotal role of engineers, like Gopi Chandra Bhagawan, who resisted concessions to Pakistan, and the influence of U.S. soft power through funding and engineering expertise under “Water for Development.” He stressed the importance of precise wording, advocating for terms like “water development for Kashmiris” over “stoppage,” and clarified that the book focuses on India’s perspective, with one chapter addressing Pakistan’s propaganda.

The panelists provided diverse insights. Dr. DV Thareja described the book as personally resonant, aligning with his experiences overseeing related projects, and highlighted global dam-building trends, particularly China’s 6,000 dams. Dr. Tara Kartha refuted Pakistan’s claims of water shortages, citing IRSA data, and discussed recent floods causing significant damage in Punjab and the depletion of glaciers, noting Pakistan’s upper riparian advantage on the Kabul River. Amb. Sharath Sabharwal praised the book’s accessibility and research, emphasizing the treaty’s lack of resilience, its controversial nature, and the need to understand the Indus Basin’s history to address future challenges, amid emotive public debates and mistrust in India-Pakistan relations. The discussion underscored the intricate interplay of water, geopolitics, and diplomacy in the Indus Basin. The event highlighted the treaty’s engineering-driven origins, its ongoing challenges, and the emotional complexities encapsulated in the sentiment that “blood and water cannot flow together.”

Border Expedition Report

High-Level Policy Dialogue on “Clean, Green, and Resilient Pathways to a Viksit Bharat”

1. Introduction

On 16 September 2025, the India Foundation and Dalberg Advisors jointly convened a High-Level

Policy Dialogue in New Delhi to deliberate on strategic approaches to realizing the vision of Viksit

Bharat @ 2047 – a developed, inclusive, sustainable, and resilient India. This gathering brought

together senior policymakers, business leaders, civil society representatives, academics, and

international experts. The dialogue focused on aligning India’s economic aspirations with a robust

climate strategy, making the case that climate action is not merely an environmental imperative

but a central pillar of national growth and competitiveness.

Participants agreed that integrating climate considerations into India’s development framework is

essential to safeguard productivity, ensure resilience, and maintain global leadership. As India sets

its sights on becoming a $30 trillion economy by 2047, the dialogue underscored the need to

embed sustainability into every level of economic and social planning.

2. Strategic Themes and Insights

2.1 Climate Resilience as Economic Strategy

Climate resilience was recognised as a foundational requirement for sustained economic output.

Projections indicate that without timely adaptation, India could face economic losses exceeding

$1.5 trillion by 2050, particularly in high-risk sectors such as agriculture, MSMEs, and urban

infrastructure. Given that over 85% of India’s districts are climate-vulnerable, the dialogue called

for urgent investments in resilient urban planning, adaptive agriculture, and protective

infrastructure.

Building resilience now will not only mitigate future disaster-related costs but also preserve

productivity and enhance social equity. Policy mechanisms that support climate-proofed

infrastructure and climate-smart agriculture were identified as immediate priorities.

2.2 Energy Transition and Green Electrification

India’s energy demand is expected to rise sharply, reaching 708 GW by 2047. To meet this need

while decarbonising the economy, the transition to clean electricity, green hydrogen, and bioenergy

must accelerate. The National Electricity Plan projects that 90% of India’s power should come from

non-fossil fuel sources by 2047.

The dialogue introduced the concept of “Electricity as the next UPI” – a digitally integrated, low

cost power grid that uses AI, IoT, and blockchain to reduce system losses and improve efficiency.

Participants stressed the need for robust policy and investment to support the development of this

infrastructure, while ensuring energy access remains equitable.

2.3 Green Trade and Supply Chain Resilience

India’s ability to compete in the global marketplace increasingly depends on carbon

competitiveness. With 68% of Indian exports destined for net-zero economies, failure to

decarbonise industrial production could result in restricted market access and loss of export

revenue.

Climate-induced disruptions such as floods and heatwaves already threaten manufacturing hubs

and logistics networks. The dialogue stressed the importance of investing in low-carbon

manufacturing, resilient infrastructure, and clean logistics. Strategic upgrades to export-oriented

industrial clusters were highlighted as vital for maintaining India’s trade leadership.

2.4 Financing the Green Transition

To meet its net-zero and climate resilience goals, India requires an estimated $150–170 billion in

annual green investment. The operationalisation of a national climate finance taxonomy was

identified as a critical enabler. This framework would provide clarity to investors, reduce

greenwashing, and support the flow of public and private capital.

Participants called for the expansion of blended finance models and de-risking mechanisms to

unlock private investment, especially in sectors with long payback periods. The importance of

developing a pipeline of bankable projects was also emphasised to catalyse institutional financing.

2.5 Global Leadership Through Climate Diplomacy

India’s growing influence in the global south presents an opportunity to shape international climate

agendas. Initiatives such as the International Big Cat Alliance, International Solar Alliance, and

Global Biofuels Alliance serve as platforms to demonstrate leadership in biodiversity conservation

and clean technology.

The dialogue encouraged the government to leverage these platforms, along with global forums

such as COP33, to promote India’s green development model and deepen South-South

cooperation on technology, finance, and climate resilience.

3. Sectoral and Governance Priorities

India’s conservation strategy must aim to expand protected areas to 10% of total land and maintain

at least 30% forest cover by 2047. This will require scaling flagship initiatives like Project Tiger, the

Cheetah Reintroduction Program, and the International Big Cat Alliance. These efforts should be

integrated with development planning and backed by strong governance and enforcement

mechanisms.

The MSME sector, comprising over 63 million enterprises, plays a pivotal role in employment and

exports but remains highly vulnerable to climate impacts. Support mechanisms such as green

financing, cluster-based innovation hubs, and digital transformation tools are essential to enable a

just transition.

Technology and innovation must drive India’s climate and development agenda. Key investment

areas include hydrogen R&D, AI-enabled climate analytics, circular economy solutions, and low

emission agricultural practices. Research institutions and private enterprises require targeted

policy and funding support to accelerate technology deployment.

Subnational governments are central to climate implementation. Empowering states and districts

through mandatory climate risk assessments, adaptation planning, and financial devolution will be

essential. Cooperative federalism must guide this approach, particularly in vulnerable regions like

Bihar, Odisha, and the Indo-Gangetic belt.

Lastly, inclusive development must remain the cornerstone of India’s climate strategy. Engaging

youth through platforms such as Viksit Bharat @ 2047: Voice of Youth, expanding sustainable

housing, and integrating climate considerations into public health are key to building community

resilience.

4. Policy Recommendations

To translate these deliberations into actionable reforms, the dialogue outlined seven core policy

directions.

First, climate priorities must be embedded across all levels of economic policymaking. From fiscal

frameworks and industrial policy to infrastructure design, climate considerations must guide

investment decisions and resource allocation.

Second, India must rapidly scale up green finance. This includes full operationalisation of the

climate finance taxonomy, development of de-risking instruments, and enhanced coordination

between public agencies and private investors to mobilise the necessary $150–170 billion

annually.

Third, conservation goals must be scaled significantly. Expanding protected areas, restoring

degraded ecosystems, and achieving zero poaching of Schedule-I species should be embedded in

India’s development and land-use frameworks.

Fourth, cleantech innovation must be fast-tracked. Government and private sector R&D

investment should prioritise hydrogen, biofuels, AI-powered energy solutions, and sustainable

agriculture technologies. National institutions must be empowered to lead this innovation drive.

Fifth, subnational governance must be strengthened. States and municipalities need technical and

financial support to conduct climate risk assessments and implement adaptation strategies.

Cooperative federalism will be key to ensuring that climate goals are met across diverse

geographies.

Sixth, MSMEs must be enabled to adopt green practices. Dedicated green financing lines, capacity

building programs, and digital infrastructure are needed to help small enterprises stay competitive

and resilient.

Seventh, inclusivity must anchor all efforts. Policies must prioritise youth engagement, promote

affordable green housing, and integrate climate-health linkages into public systems. Community

led conservation and adaptation models should be scaled to ensure local ownership and impact.

5. Conclusion

The High-Level Dialogue reaffirmed that India’s path to becoming a developed economy by 2047

must be clean, green, and resilient. Climate action is not a constraint on growth; it is the most

strategic enabler of sustainable prosperity and global competitiveness.

India has the opportunity—and the imperative—to lead the global green transition. The insights and

recommendations generated through this dialogue offer a roadmap to accelerate climate-smart

development. India Foundation and Dalberg Advisors remain committed to supporting the Ministry

of Environment, Forest and Climate Change in translating these priorities into policy, partnerships,

and implementation frameworks for a climate-resilient Viksit Bharat.

Chair: Dr. Ram Madhav, President, India Foundation

Special Addressee: Mr. Jayant Sinha, Former Minister of State, Government of India

Invitees for the High-Level Strategic Interventions

1. Ms. Akshima Tejas Ghate, Managing Director, Rocky Mountain Institute India

2. Dr. Alok Sikka, Country Representative – India, International Water Management Institute

3. Dr. Amit Kapoor, Chair, Institute for Competitiveness

4. Mr. Amit Prothi, Director General, Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure

5. Ms. Archna Vyas, Global Director of Policy and Communications, Gates Foundation

6. Ms. Cecilia Tall, Counsellor for Science and Technology, Embassy of Sweden

7. Ms. Charu Chadha, Consultant – Asia Regional Office, The Rockefeller Foundation

8. Mr. Deo Datt Singh, Director, People’s Action for National Integration

9. Mr. Jatinder Cheema, Principal, JC Law Advocates and Solicitors

10. Mr. Kamlesh Kumar Mishra, Joint Secretary, 16th Finance Commission, Government of India

11. Mr. Koyel Kumar Mandal, Director, Climate – India, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation

12. Ms. Mahua Acharya, Founder and CEO, International Energy Transition Platform

13. Dr. Manoj Singh, Additional Member, Railway Board, Government of India

14. Mr. Mudit Narain, Energy Advisor, Social Alpha

15. Mr. Nabin Kumar Roy, General Manager, National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development

16. Mr. Pawan Mulukutla, Executive Programme Director, World Resources Institute India

17. Mr. Randheer Singh, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, ForeSee Advisors

18. Dr. Ravindra Kumar Singh, CGM, Small Industries Development Bank of India

19. Dr. Satya Prakash Yadav, Director General, International Big Cat Alliance

20. Ms. Seema Paul, Programme Director, Sequoia Climate Foundation

21. Dr. Sharath Rao, Fellow, Centre for Social and Economic Progress

22. Mr. Shombi Sharp, United Nations Resident Coordinator in India

23. Mr. Vaibhav Pratap Singh, Executive Director, Climate and Sustainability Initiative

24. Mr. Vivek Sen, India Director, Climate Policy Initiative

Curators

1. Mr. Jagjeet Singh Sareen, India Head, Dalberg Advisors

2. Mr. Shashvat Singh, Senior Research Fellow, India Foundation

Interaction with Ms. Maja Groff

On September 16, 2025, India Foundation organised an interaction on the topic, “Global Governance Solutions to the Climate Crisis.” The speaker, Ms. Maja Groff, is an author, international lawyer, and Convenor of the Climate Governance Commission, which empowers organisations and leaders to focus their efforts on transitioning to a net-zero, climate-resilient economy. The interaction was attended by an eminent group of policy advocates and practitioners working on climate change. The interaction was chaired by Mr. Côme Carpentier, Distinguished Fellow at the India Foundation, who, after welcoming the speaker, briefly set the background for the talk, underscoring the frequency of extreme climate events and the polarizing world opinion on climate action.

Ms Maja Groff commenced the interaction by offering an overview of the Climate Governance Commission, which comprises of 19 eminent persons, including former heads of states, former ministers, boasting of a diverse geographic representation.

She underscored that the current predicament posed by the climate crisis offers an opportunity for streamlining international governance of the environment. She advocated for a comprehensive approach to planetary boundaries, which necessitates a system of Earth governance. Cautioning that 6 of the 9 planetary boundaries of the ecology had already been breached, she brought attention to the impact of climate change on the global economy, which, due to climate crises and disasters, is expected to shed 19% of its GDP. Insurance and actuaries have borne the immediate brunt of the economic effects of climate change, as insuring against increasingly unpredictable, all-encompassing, and cascading effects of climate change becomes a challenge.

Ms Groff underlined the need to protect all ecological systems, treating climate and biophysical systems as the common heritage of humankind. Outlining the intent of the organisation to advocate for institutionalisation of this principle to facilitate collective management, she opined that legal–institutional arrangements must espouse adaptive models of governance to address the fast-evolving circumstances. While agreeing that frameworks have contributed to devising strong norms, she opined that the proliferation of bilateral agreements has not been accompanied by timely implementation.

She demonstrated the contribution of the Climate Governance Commission toward developing tangible, time-bound policy proposals—e.g., during the Conference of the Parties (COP) in 2023—to fashioning next-generation institutions and empowering the United Nations Environment Programme. She described the need to de-fragment existing institutions and create emergency platforms to absorb global climate shocks and risks. Furthermore, she informed the guests of the Commission’s plans to prioritise proposals for the upcoming COP in Brazil. She concluded her remarks by emphasising the need for a corporate ecosystem, which will emerge from an alliance of the private sector and civil society, advancing a like-minded approach for reforms to face transnational challenges.

A lively round of Q/As followed, where the recent policies of the Trump Administration on climate management drew the attention of the guests. Ms Groff traced the frequent changes in climate policies brought about by shifts in dispensation in Washington, DC, since 2015. The discussion also revolved around the alternative arrangements and policy leaders in the event of the US retrenchment from international climate governance. Ms Groff argued that, given the gravity of climate risks and their economic consequences, alternative centres like the BRICS and the European Union must fill the void left by US policies on the environment and climate finance.

Ms Groff was felicitated by Capt. Alok Bansal, Executive Vice President, India Foundation.

IF-IHC Panel Discussion on ‘Analysing the Trajectory of the Indo-U.S. Relations’

India Foundation, in collaboration with the India Habitat Centre, organised a panel discussion on ‘Analysing the Trajectory of Indo-US Relations’ on 11 September 2025 at India Habitat Centre, New Delhi. The session brought together distinguished experts like Prof C. Raja Mohan, Distinguished Fellow, CSDR; Visiting Professor, ISAS, NUS; and Chair, Editorial Advisory Board, India’s World; Ms. Barkha Dutt, Senior Journalist and Editor, Mojo Story; and Shri Arun Kumar Singh, Former Ambassador of India to the United States, Israel, and France. The discussion was moderated by Captain Alok Bansal, Executive Vice President, India Foundation. The panel deliberated on the evolving contours of the Indo-US partnership, focusing on opportunities, constraints, challenges, and possible trajectories for the future.

Prof C. Raja Mohan opened the discussion by questioning the pace at which major powers recalibrate their relationships. He highlighted the robust $200 billion bilateral trade ties between India and the United States, observing that “trade issues are serious although negotiable.” He underlined that traditional flashpoints such as Jammu & Kashmir, nuclear weapons, and Pakistan have receded in salience, while trade has emerged as the central issue. Stressing that diplomatic engagement alone cannot resolve trade frictions, he called for self-reflective economic reforms within India, adding: “Relationships will continue to change. We need to adapt and analyse them.”

Ms. Barkha Dutt offered a perspective on America’s internal polarisation, remarking that political violence has been historically ingrained in its society. She argued that the United States today appears to be “dissembling and diminishing.” Noting India’s delicate balancing act, she stated: “We are faced with a deeply opaque China and a deeply volatile United States. India seems to be walking a tightrope.” She added that for the common citizen, Indo-US relations are less about technical trade negotiations and more about sovereignty and autonomy—about not being bullied.

Amb Arun Kumar Singh traced the trajectory of Indo-US relations into the future, pointing out that while political leadership may be fragmented, functional cooperation between the two nations continues steadily. He acknowledged the United States’ position as the world’s leading economic power and argued that India cannot afford to neglect this relationship: “The US offers to India what Russia cannot. We have no option but to build this relationship.” He cautioned, however, that India must hedge and diversify its partnerships to preserve autonomy, noting that over-dependence could mirror the vulnerabilities faced by Europe, Japan, Indonesia, and Vietnam. He urged the US to build a “partnership of confidence with growing convergence.”

Captain Alok Bansal, in his concluding reflections, drew a cultural distinction between occidental societies like the US, which readily adapt to changing circumstances, and oriental societies like India, which are more rooted in sentiment and slower to change. He highlighted that if, even in the aftermath of 9/11, trade rather than geopolitics or security remains a key theme in India-US discussions, it demonstrates the centrality of economic issues. He further observed that America’s real leverage over India lies not in tariffs but in visa restrictions, which significantly impact people-to-people linkages.

The discussion underscored that while the Indo-US relationship is evolving amidst shifting and economic contexts, it remains indispensable for both countries. Trade has emerged as the defining axis, even as strategic, political, and cultural considerations continue to shape the engagement. The panel agreed that India must pursue reforms, balance partnerships, and assert its autonomy, while the US must strive to build a relationship grounded in confidence and convergence.

Briefing by the Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Japan to India and Bhutan, H.E. ONO Keiichi

On September 8, 2025, India Foundation organised a closed-door briefing with the Hon’ble Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Japan to India and the Kingdom of Bhutan, H.E. Mr. ONO Keiichi. The briefing was focussed on the outcomes and opportunities from the two-day visit of India’s Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi to Japan from August 29-30, 2025, as well as his meeting with his Japanese counterpart, the then-Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba. The briefing was chaired by Captain Alok Bansal, Executive Vice President of India Foundation, who welcomed the Ambassador and introduced the subject of the briefing. The briefing was attended by distinguished guests, including former military commanders, former diplomats, defence experts, journalists, and policy analysts with particular interest in the trajectory of Indo-Japan relations.

The discussions took place under Chatham House rules and, set against the backdrop of PM Modi’s visit to Japan, encompassed the whole gamut of the bilateral relationship. They focussed on the aspects of continuity and the expansion of the Special Strategic and Global Partnership in its 10th year. The briefing dwelled on the mutual complementarities explored during the visit, and the need for adopting a collaborative outlook on economic and security matters to provide clearer impetus to their strategic partnership. The discussions emphasised on the need for stronger cooperation in international institutions to weather the headwinds in geopolitics. The delegates concurred that the following Conference of Parties in Brazil will provide a critical platform for negotiations for just decarbonisation and climate financing pathways.

The briefing identified the potential for boosting private investment from Japan into India and the opportunities in India’s business environment, especially in its Northeast. The dignitaries also drove their attention to the strides made in technical and financial collaboration in high-speed rail mobility, as well as the potential for cooperation in next-generation mobility, meeting the countries’ climate targets, and achieving integrated spatial development in the areas served. The discussants explored opportunities in micro, small, and medium-scale enterprises (MSMEs), building resilient supply chains and logistical channels, and defence. The discussions also ranged the regional shifts in South Asia, Africa, and East Asia, and the potential for concerted action of Japan and India to provide solutions to shared problems.

The meeting ended on an optimistic note, as the participants lauded the progress of the bilateral partnership and expressed hope for the two countries to participate in each other’s economic development. After a lively round of Q/As, the Ambassador was felicitated by Air Marshal (Retd) PK Roy, Member, Governing Council, India Foundation.

An Interview with Amb Shyam Saran, Former Foreign Secretary, on “India’s Neighbourhood: Navigating Geopolitical Shifts”

Dhruv C. Katoch:

We are living in highly volatile times. South Asia is not immune to the effects of global power politics, and for various reasons, the region is troubled by internal discord—political, economic, and security-related. In this podcast, we will discuss some issues concerning India’s neighbours. We are honoured to have Ambassador Shyam Saran to explore these topics. The Ambassador is one of the most respected voices on global and regional affairs. He has served as India’s Foreign Secretary and is also the recipient of the Padma Bhushan. Welcome, Ambassador. Let me begin with Bangladesh, with whom we have maintained very friendly relations, but those ties are now starting to fray. What are the main factors shaping Bangladesh’s current political and socio-economic situation, and how might these changes affect its internal stability as well as India’s security, trade, and the broader regional dynamics in South Asia?

Shyam Saran:

Thank you very much for inviting me to speak with you on topics that are very important for India’s foreign policy. So, concerning Bangladesh, as you said, we had an excellent run in a sense with Sheikh Hasina being in power. People sometimes complain that we put all our eggs in one basket, and we should have reached out to other political forces in Bangladesh. I think they neglect the fact that some very major positive developments took place during the past 15 years or so. We resolved the border issue, which had been pending for a very long time. We managed to get agreement, not 100%, but substantially, on the sharing of river waters. We established very strong cross-border connections with Bangladesh, including the revival of river transportation, which was once the lifeline for the northeast of the subcontinent. We became a major power source for Bangladesh’s industry. Without the supply of electric power from India to Bangladesh, the textile industry in Bangladesh would not have progressed as much as it did. We became a significant market for Bangladesh’s products, including textiles, which are their major export. In the security sphere, the sanctuaries that many of the insurgent groups used to have in Bangladesh came to an end. So, for anybody to say that we did not play this game right, I disagree with that. When an opportunity arose, we made full use of it. And even if the political pendulum swings to one side and we have to cope with the consequences of that, the pendulum can also swing to the other side, and we should be ready for that change. So, we should not get too panicky about the situation that has emerged. We should try to deal with it as best as we can.

One thing to consider is that, when examining the situation in Bangladesh, you must not forget its history. Remember that even when Bangladesh became an independent country, there was no complete political consensus, even within Bangladesh, regarding this separation from Pakistan. Nearly one-third of the population did not support Bangladesh’s separation from Pakistan. For example, the Jamaat, an influential force, although it doesn’t win elections, has never reconciled itself to the separation of Bangladesh. Several other people may be more inclined, as far as the attachment to Islam is concerned, to believe that being an Islamic country is more important than being a Bengali country. So, we have to be mindful of the fact that various forces are at work inside Bangladesh.

Regarding the domestic situation, we can do very little to influence those dynamics. So, what is the best course of action? The position that the Government of India initially took was communicated during the visit of our Foreign Secretary to Bangladesh. What message did he convey to the chief advisor? He stated that, despite any political relationship difficulties we may be facing, India will continue with the broad spectrum of cooperation we have always maintained with Bangladesh. This includes the supply of power to Bangladesh, cooperation on river waters, and providing access to our markets, including transit arrangements, which are very important for Bangladesh. We do not intend to interrupt these efforts, and we hope that, despite any political issues, Bangladesh will also recognise the value in maintaining this cooperation.

This is where political issues in Bangladesh have begun impacting some of our cross-border connections. How should we respond? I believe we should remain calm and continue to be prepared to cooperate whenever the other side is willing. However, when it comes to defending our interests, particularly our security concerns, we must be cautious. We need to be aware of where our interests are being affected, and nobody should doubt that if our interests are harmed in any way, we will take appropriate remedial action. Beyond that, we remain open to resuming cooperation with Bangladesh when the situation improves. We hold goodwill for the people of Bangladesh, as we have no issues with them. That should be our approach during this challenging time.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

Just a quick follow-up question: the elections are scheduled for February. First, do you think they will happen? Is it likely that they will (or should they) result in a democratic establishment? I mean, will they genuinely follow the democratic process, or will it simply be the Jamaat taking over?

Shyam Saran:

Well, the fact that they have said the Awami League cannot participate in these elections suggests that it may not be as democratic as one would hope, because the truth is that the Awami League is, in a sense, being marginalised within the political system. The fact that there is a concerted effort to try to delegitimise the Awami League shouldn’t be overlooked. Even today, 30% of the population still supports them. So, if you’re claiming that the preferences of at least 30% of your population cannot be considered, then how can it be truly democratic? We must take that into account. Incidentally, the BNP, which has been the main opposition party, also believes that a competitive political environment is necessary. They are not opposed to the Awami League participating in the election, or at least that’s the impression I have received. As for Jamaat, I am uncertain whether they will achieve significant gains in the polls, given that, as I mentioned, despite their influence, they have never secured a substantial number of seats in the Bangladesh Parliament.

We have observed that, whether or not they succeed in elections, they still become an influential constituency. Now, for the Jamaat, India is a warning sign because they blame us for the separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan. They also blame us for what they see as secularisation of the polity in Bangladesh. Therefore, as we see today, the Jamaat has gained a significant level of influence. If this situation continues and becomes, in a sense, institutionalised, then that is not very good news for India. However, we should also not underestimate the importance of the economic connection between India and Bangladesh. I am hopeful that many of the interdependencies established over the last 15 years or so will remain strong enough to help us through this period of some turmoil.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

Now I will move on to another country, our neighbour Nepal. Our relations with Nepal have traditionally been very close, especially considering the nature of family ties we have shared; there is a commonality of religion, culture, history, civilisation, and complete compatibility. However, we have tensions with them. There is a historical reason for this. Currently, internal problems within Nepal tend to influence the situation. These issues often impact the India-Nepal relationship. How do you see this playing out in the present climate in Nepal, where they face their own political and economic challenges, and China is also emerging as a significant player?

Shyam Saran:

I have been an ambassador to Nepal, and I believe I have some familiarity with the country, though perhaps not a great deal, but enough to know that the most important asset we possess regarding Nepal, which also applies to several neighbouring countries, is the people-to-people relations. Very strong people-to-people relations. You mentioned that we have these cultural links and familial ties, and by the way, the familial links are not only with the Madhesis and the states of Bihar and UP. There are also very strong familial connections with the so-called Pahadi population living in the hills. People tend to think it is only the Madhesis, but it is not. These are also very strong connections. Therefore, the challenge for India has always been how to leverage this very strong people-to-people and cultural affinity between the two countries to influence the state-to-state relationship positively. Because if there is a problem, it exists only there. It is not with the people; it is the political path.

One point I must emphasise is based on my own experience: you have to recognise that you are a very large country surrounded by smaller neighbours. It should come as no surprise that these neighbours may feel somewhat anxious about the possibility of being overshadowed by the larger power, which is natural. We often feel similarly when faced with a superpower, and we try to balance that influence. Therefore, we should not be overly sensitive about it. We need to understand what that implies, which is how we can develop a diplomacy of reassurance with our neighbours. This is especially important for a country like Nepal. The key is to show them that we genuinely wish them well and are willing to be partners in their economic and social development because that truly matters to them.

Now, two points regarding how we approach this. One of the challenges we face is the presence of various constituencies in Nepal. If you start saying ‘this is my friend’ or ‘this is not my friend’, it creates a problem. We must avoid being perceived as taking sides in what is essentially a domestic political dynamic. This is very important. India should not be seen as part of that. If we are not involved in that, we are in a much stronger position. The second point is that you should not view your relationship with Nepal solely through the lens of China. If every action in Nepal is framed by what you believe China is doing, you will encounter difficulties. Trying to match China in the way it exerts largesse, which I see as a kind of game, is not advisable. Why? Because you should leverage your areas of strength, rather than attempt to mirror Chinese strengths. This requires careful consideration. For example, consider one area — proximity. China faces more difficulties accessing Nepal than India. Isn’t that correct? Why is it that, despite years of efforts, the Chinese have been carving through mountains and building roads, or even talking about railways? Why, given our geographical advantage, have we not been able to achieve similar progress?

During my time as an ambassador in Nepal, I noticed that travelling from Nepal into India by road could give the impression that one was coming from a relatively developed country to a less developed one, given the poor state of our roads. Now, there has been a significant improvement in that regard. There has also been progress in attempting to revive, for example, some of the rail links that existed before. We have finally started working on a hydroelectric power cooperation between the two countries. These are positive developments, but with respect to Nepal, as with some other neighbouring countries, our overall approach should be to make India the engine of growth for the entire region. You can achieve this because the very asymmetry of power you hold over your smaller neighbours—which, in one sense, is a disadvantage because everyone fears you—could also be turned into an asset, allowing India to become the driving force of regional growth.

Supposing you open your market to everything that your neighbours can produce and sell to you, this will still be a small fraction of your market. Why not become the transit country of choice? Specifically, for Nepal, why insist that only this port can be used; no, only this highway is permissible. Tell them that you will give them national treatment, allowing them to use any channel for exporting or importing that they prefer, whichever is most convenient. You should position yourself as Nepal’s partner of choice. There are so many advantages to truly cooperating with India that I see no reason to look elsewhere. For example, consider the impact of just one project I mentioned when I was an Ambassador — the Barauni-Amlekhganj pipeline. Previously, there used to be a lot of pilferage when tankers delivered supplies, and accidents were common. Now, there is a completely safe supply of gas and petroleum to Nepal. These are the kinds of deep interdependencies that benefit both Nepal and us. That should be the approach we adopt. Sadly, there still exists a mindset that sees something hostile outside our borders. You need to change your mindset. When you do, many more possibilities open up.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

That’s been very well brought out. Let me get down to the next contentious issue. Given Myanmar’s ongoing civil conflict since the 2021 military takeover, and its implications for India’s Act East Policy as well as security in the North East, how do you assess the evolving internal power dynamics in Myanmar, and what potential consequences do you foresee for India amid increasing US involvement in both Myanmar and Bangladesh?

Shyam Saran:

This situation will likely persist for some time because neither side is in a position to overcome the other completely. Furthermore, there are powerful external forces involved, notably China, but not only China; for instance, Thailand is also engaged in what is happening, though China is especially prominent. Therefore, part of the issue for us is that there is little we can do to influence the course of the civil war there. Whether you like it or not, you are in a somewhat defensive position.

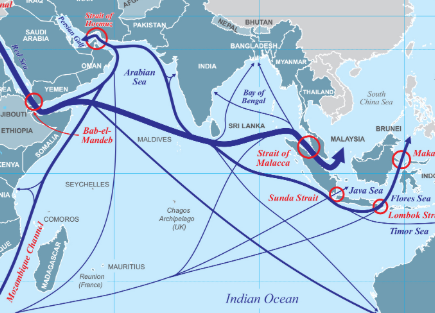

So, there is sometimes wisdom in recognising that you don’t have much leverage in this area. What can you do? I think what is crucial for India is that we share a 1400 km-long border with Myanmar. Some of our most sensitive Northeastern states border this region. We have experienced a history of insurgency and other issues, so ensuring the safety and security of this frontier is a top priority. Our focus should be on trying to protect ourselves, albeit not entirely, from the events that occur on the other side, while acknowledging that our influence on them is limited. Problems will arise because you have the Chins on the other side and the Mizos on this side, who share very strong inter-ethnic ties. Likewise, the Nagas are on both sides of the border. Ethnic spillovers are an inherent reality. Over the years, we have allowed these cross-border linkages to persist because they are vital for the livelihoods of those living near the border. Therefore, unless it directly impacts your security, there is no need to overreact or interfere too much with these interactions.

But what is truly concerning for us is whether this situation is creating the possibility of greater Chinese influence in a neighbouring country than would otherwise occur. That is a risk we need to be aware of. Even when I was ambassador in Myanmar, Chinese influence was growing very rapidly. Part of the reason we reached out to the military government, and why we tried to engage with them more than before, was because, if you remember, we strongly supported Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD. While we did not cease supporting them, we also engaged with the generals. When I reached out to the generals, I found they were quite open and a little concerned about their over-dependency on China. They were therefore willing to increase cooperation with us. There are indeed opportunities here. Maintaining some of the links we have with the military government makes sense because they remain the most organised and powerful force in Myanmar. Completely cutting off engagement would not be sensible. The period of turmoil and uncertainty will likely continue, but as long as we focus on securing our very sensitive borders and stay engaged with key players on the other side, we will generally remain in a strong position.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

Now, as a side note on Myanmar, we sent one of our distinguished fellows there, and she conducted significant research, and everything you have mentioned has been confirmed by her. Now I will turn to one of the smaller island nations. Prime Minister Modi’s visit to the Maldives last month, during which six MoUs were signed, occurred after a period of heightened tensions marked by anti-India sentiment in the Maldives. What factors do you believe contributed to this change, and what impact might the visit have on the future course of India–Maldives relations?

Shyam Saran:

To the extent that countries are mindful of their larger interests and wish to pursue those interests, I see no reason why this more positive trend in our relationship cannot continue. I believe it will. Why do I say that? There is indeed a very strong constituency in the Maldives, similar to what we see in some other neighbouring countries, who believe their interests are better served by having a closer relationship with China, opening up to Chinese investment, and taking large credits or loans from China to develop their infrastructure. How can we object to that? If a country, whether a neighbouring one or not, cannot match China, and it turns to China for infrastructure development, there is no way India can object to that.

But observe what has happened. I am familiar with the Maldives because I had a very close relationship with President Nasheed. We were working during his presidency to foster much more substantial economic cooperation between the two countries. Unfortunately, due to the coup, we could not see this through, but I am aware of the different opinions that exist. A strong group in the Maldives believes that their interests are best served by a closer relationship with China, mainly because China can assist in their infrastructure development, which no other country can. Yes, that’s true. Additionally, before COVID, China had become the primary source of tourism for the Maldives, which generated significant foreign exchange for the country. There are many reasons why the Maldives thought that engaging more with China would be advantageous, and in pursuing that, perhaps downgrading the relationship with India might bring even greater benefits.

But what has happened? I will give you two examples. First, the bridge between the main island and the airport island. Major infrastructure projects, which are highly beneficial to the Maldives, cost a lot of money and were financed through credit. What is the situation now? The toll for crossing the bridge is so high that nobody uses it except tourists. The local people still prefer the ferry because it is much cheaper. As a result, the toll revenue is insufficient to repay the loan and interest. Clearly, infrastructure development is vital for any country, but it’s also essential that such projects generate income to cover their costs. Merely building infrastructure is pointless if it cannot produce income. That’s what happened with that project. Similarly, there was a large-scale low-cost housing project in the Maldives. Now that housing has become so expensive that no low-income person can afford it. Most of it remains vacant. I believe that in both the Maldives and earlier in Sri Lanka, they realised that while infrastructure development, especially with Chinese assistance, sounds impressive, it can sometimes become a heavier financial burden.

This is the reality that the new government eventually faced: instead of being a support for the Maldives’ development, it became a millstone around their neck. While 5-star hotels can obtain their supplies from Singapore and Dubai, what about the ordinary people of the Maldives? All essential supplies come from India at prices that we Indians pay. Remove that, and you’ll see what happens to the cost of living there. So, I believe we also played our cards well. I commend the government for not taking the bait. They stayed calm and did not respond with the same level of abuse, which also played a significant role. The kind of diplomacy practised is crucial. This approach allowed them, without losing Face, to return to a good relationship with India. Therefore, we are in a good position there, and by the way, we are also in a good place in Sri Lanka.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

So, in Sri Lanka, the political landscape shifted last year, and they now have a left-front government. Naturally, there was some concern about what might happen. But we have seen that nothing significant has occurred. Even with the left-front government, the relationship remains very good, and I think that’s a healthy sign. What has contributed to that? Is it the same as what happened in the Maldives?

Shyam Saran:

Just one thing has contributed, and that is when Sri Lanka was in a deep, deep crisis, we helped them out. India was the only country that provided significant assistance, helping the ordinary people of Sri Lanka deal with that crisis. We supplied them with rice, fuel, and fertilisers. Regarding their financial issues, we provided them with a swap line. So, if you look at how we were able, at a time of deep crisis, to support Sri Lanka, we were ready to reschedule our loans so they could obtain an IMF loan. The Chinese would not provide that letter until much later. What is very important is that in public perception in Sri Lanka, they suddenly realised, look, when we were struggling, only one country came and helped us. That has made an enormous difference, and I think the new government that has come in is aware of the fact that there is a shift in public perception. Therefore, maintaining a strong relationship with India is beneficial in terms of the public there.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

Right. Ambassador, I’ll move on to my final two questions now. I don’t want to cover the entire scope of the India-Pakistan relationship, as I don’t see much progress occurring, especially after Pahalgam and Operation Sindoor. However, I would like to address the internal situation within Pakistan, which is characterised by three primary challenges: economic, internal security, and political. In your view, do you think there will ever be, at least in the foreseeable future, a situation where politics can maintain control over the military, or is the military destined to rule, at least for the next few decades, if nothing else?

Shyam Saran:

I believe, as uncomfortable as it may be, that the only organised disciplined force in Pakistan is the army. Whenever there has been a crisis or significant unrest in the country, the fallback has invariably been the armed forces. That remains unchanged, by the way. So, if you are considering a future situation where the army is no longer influential, I am afraid that isn’t going to happen.

Also, be aware that the only time we have managed, relatively speaking, to improve relations between India and Pakistan has been when the army has been in control. The army there believes that improving ties with India is in its interest. So, this is the reality. Now, the third point we often forget is that the desire for parity with India is deeply ingrained in Pakistan. I wrote in one of my op-eds: “If you do five tests, I will do six.” There is always this mindset that I have to be one step ahead, to prove that I am superior to you. The belief that one Pakistani soldier is equal to ten Indian soldiers reflects this psychology. You may laugh at it, but it is very deeply rooted. Therefore, you must address this kind of mentality.

Having said that, the one thing that my view differs slightly from what we are trying to do at the moment is that I have always believed it is important, even when very difficult, to maintain some engagement and dialogue with Pakistan. Because, at the very least, it provides insight into their thinking. It offers a warning signal if things are heading in the wrong direction. Currently, it feels like a black box, and that is not ideal. As you mentioned, many internal developments and internal dynamics are happening. Part of our problem is how much knowledge India currently has about what is happening inside Pakistan. What is its economy doing? How vulnerable is this economy? What are its strengths? What are the sources of resilience that, whether you like it or not, still seem to exist?

So, unless you understand your adversary and how he thinks, it’s very challenging to develop a counterstrategy. My view is that you should safeguard your interests with respect. Keep your powder dry, but engagement is necessary. Even during the worst times of the Cold War, remember that the Soviet Union and the US still communicated. As a professional diplomat, I would say this is very important. But today, we are in a difficult situation, primarily because of recent events involving the US. This is a new, more dangerous situation. Why do I say it’s dangerous? Look at the statement made by the Army chief in Florida. He might think this is a good time to provoke India, believing he is protected by both China and the US. So, we are in a vulnerable position, and I hope we are aware that such thoughts might be on his mind.

Dhruv C. Katoch:

Ambassador, I have left China for the last question for this podcast. China today faces a range of internal challenges, including an economic slowdown, demographic pressures, and tightening political control. How do you think these domestic concerns are shaping Beijing’s approach to its relations with India, particularly in the context of ongoing border tensions and regional competition?

Shyam Saran: