Introduction

Myanmar has been in a state of chaos since the military coup in February 2021, when the Tatmadaw seized power from the Aung San Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy (NLD). The country entered a period of civil war, with the military junta facing numerous opposition groups, including armed ethnic organisations and the civilian-led People’s Defence Force (PDF), which was formed under the National Unity Government (NUG) in response to the military coup.

What was once seen as a military effort to restore the Constitution’s integrity and uphold the rule of law has come full circle. The Tatmadaw, which regards itself as the guardian of national unity, is now confronting Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs), launching attacks on military assets and democratic forces fighting to dislodge the military junta.

The junta[1], on the other hand, has announced elections in December 2025 with the caveat that Myanmar achieve a state of relative peace and stability. The national census conducted last year in preparation for the polls was also opposed by the EAOs and prevented from being carried out in the EAO-controlled areas. Initial reports suggest that if elections were to take place, they would be in 102 out of the 330 townships in the country, as the remaining are predominantly EAO-controlled areas. While the resistance has pledged to oppose the outcome of the elections, the junta remains firm in asserting the unity of Myanmar.

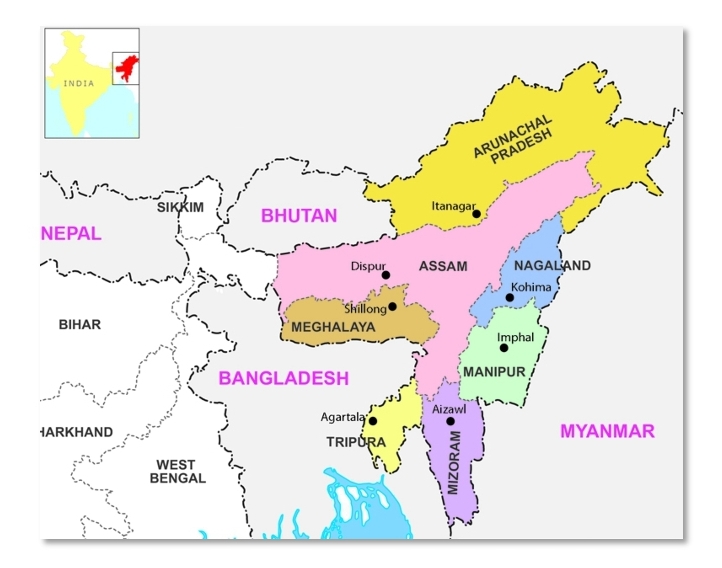

Finally, the increasing internal complexity in Myanmar has significantly impacted India, which shares over 1643 km of porous land borders with the northeast region and has transnational ethnic links. Furthermore, countries such as China, Russia, and the United States have also expanded their influence, either through the EAOs or the junta, and in China’s case, through both. There are signs of intense competition over critical earth minerals and other natural resources. Therefore, the effects of the civil war-like conflict go well beyond a refugee crisis for India, leading to lasting consequences for the northeastern region.

Myanmar – Traversing From Elections in 2021 to Elections in 2025

There has been much debate about territorial control in Myanmar, with the main question being ‘who controls more territory in the ongoing conflict?’. This assessment aims to identify the ‘winning side’. While some argue that the EAOs have gained more territory, others believe it is roughly evenly split. However, when considering the population, it becomes evident that the junta controls a larger number of people.

The other issue that arises is governance and administration. While most Tatmadaw-controlled areas are functional concerning basic necessities and relative peace, the EAO-controlled regions have been isolated. With the absence of proper administration and essentials such as electricity, petrol, or even functioning schools, the outlook for the future remains bleak. The current circumstances are negatively impacting ordinary people, leading to increased migration.

However, while the junta has announced elections in Myanmar to restore democracy, it is important to note that the polls can only be held in areas under military control. UEC, via notification No. 56/2025 dated 20th August, announced the schedule for the first phase of the general election, which is set to take place on 28th December 2025. Elections will be held in 102 townships, including six in Kachin State, two in Kayah State, three in Kayin (Karen) State, two in Chin State, twelve in Sagaing Region, eight in Bago Region, nine in Magway Region, eight in Mandalay Region, five in Mon State, three in Rakhine State, twelve in Yangon Region, twelve in Shan State, eight in Ayeyarwady Region, and eight townships in Naypyitaw (National Union Territory).

EAOs and the NUG have boycotted the elections, vowing to continue their struggle for liberation against the regime of the Tatmadaw. The NUG is an umbrella body that emerged after the coup in February 2021. It has brought together, albeit loosely, most of the EAOs except for some, such as the Arakan Army from Rakhine State, among others. The EAOs under the NUG are demanding a complete separation of the Tatmadaw from politics in Myanmar, which would require amending the 2008 Constitution, as it reserves 25% of the seats in national and local parliaments. A statement by the NUG on 24th August 2025, in response to the announcement of elections, stated that “the results of the 2020 elections remain valid” and that “they (NUG) will continue to resist by every means available – any attempt to impose a sham election at gunpoint”.

Regarding geography, Myanmar borders India and Bangladesh to the west, China to the north and northeast, and Laos and Thailand to the east and southeast. It also has coastlines along the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal in the south and southwest. India shares 1643 km of porous borders with Myanmar, mainly in large EAO-controlled areas like Chin State, Sagaing Region, and Kachin State. Additionally, southern Chin State borders India and is controlled by the Arakan Army from Rakhine State.

Therefore, it becomes essential for India to remain vigilant about security implications in the near future. Against the backdrop of increased migration due to conflict and shortages of necessities, which have led to a surge in illicit activities along the border, India must develop a viable strategy to address the inevitable threats. There is also an added risk of Indian Insurgent Groups (IIGs) reviving in Myanmar, as well as international vested interests exploiting these fault lines for more intense geo-strategic confrontations.

Increase in International Presence

China

Since the coup in 2021, China’s influence in Myanmar has only grown. Not only do they control some of the EAOs, but they also pressure the Tatmadaw when necessary. They also have a special envoy for Myanmar who often negotiates between the Tatmadaw and the EAOs. The most recent example of this assertion of influence was when Chinese special envoy to Myanmar Deng Xijun arrived in Lashio[3] to supervise the handover of the capital of the northern Shan State to the military junta by the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). Surprisingly, MNDAA suffered significant losses, including hundreds of soldiers who lost their lives fighting for Lashio. This territorial expansion made the military junta uneasy, leading to Chinese involvement in negotiations for a withdrawal.

The challenge for China is that the Tatmadaw has not been able to stabilise Myanmar or effectively consolidate its power. Consequently, this threatens China’s infrastructure investments. Whether it is the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), its oil and gas pipelines, or the Kyaukphyu deep seaport, without political stability and control over EAOs, China’s alternative to its “Achilles’ heel”, the Strait of Malacca, will remain vulnerable. China’s natural gas and oil pipeline, which begins in Kyaukphyu city of Myanmar’s Rakhine State, passes through the Magway Region, Mandalay Region, and Shan State before entering China’s Yunnan region, serving as China’s springboard to ASEAN, just as the northeast region is a springboard to ASEAN for India. Importantly, Gwadar port, part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and Kyaukphyu port provide China with an advantage in strategically containing India and blocking access to the West and East.

Additionally, Western policies have over the years almost coerced Myanmar into turning towards China and Russia for support. Washington had even accused Myanmar’s defence ministry of importing nearly USD 1 billion worth of materials and raw materials to manufacture arms.[4] China continues to be Myanmar’s main source of foreign investment, with 40% of its foreign debt owed to China.[5] Furthermore, there is a risk that sanctions could worsen China’s debt trap strategy. Considering China’s projects in Myanmar that have advanced under the junta, and the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), India has every reason to be concerned about China’s interest in a ‘back door’ access to the Indian Ocean. Additionally, Myanmar’s rich oil and natural gas reserves, along with its fragile geographical position, have made it a key focus in China’s future plans.[6]

United States of America

The US has recently changed its stance towards the military junta and lifted sanctions on its allies after Senior General Min Aung Hlaing praised President Donald Trump. While Human Rights Watch described the move as extremely worrying, the shift in US policy is significant and abrupt.[7]

Of late, Myanmar ranks among the top four countries in the world for producing rare earth elements. The highly profitable illegal mining, coupled with political instability, has prompted EAOS and other groups to seek markets beyond China. Unregulated mining and ongoing political turmoil have fostered an environment of clandestine dealings and profit sharing among militias and insurgent groups. Chin and Rakhine States, along with Sagaing Region and Kachin State, are also rich in resources such as aluminium, nickel, iron, chromite, oil, and gas. Most notably, these areas are abundant in heavy rare earth elements (HREE), like dysprosium and terbium, which are considered the most critical elements among rare earths.[8] EAOs are actively seeking partners for exploration in territories under their control.

The US seems to have a vested interest in the market. Early in August 2025, with the lifting of sanctions, some junta leaders reported that the Trump administration had been approached with proposals to access Myanmar’s critical earth minerals and HREE.[9] Incidentally, the US also lifted sanctions from the military junta leadership in July 2025, which has been seen as a thawing of relations between the US and the military junta. If the US were to get involved and shift its policy towards the military junta, India can be assured of contestations between China and the US in its own backyard.

Conclusion

As the military junta moves forward with its plans for elections, it is expected that the offensive against the Tatmadaw by the EAOs will intensify. However, without a central figure like Aung San Suu Kyi, the resistance will find it difficult to coordinate a united offensive and develop a cohesive political strategy. Reports indicate that Suu Kyi is in poor health and under house arrest. Furthermore, the NLD has not registered for the elections. Given the current situation, it is likely that the military-backed USDP will assume power, supported by smaller political parties from EAO-controlled areas and some EAOs involved in the peace process. Considering that the 2008 Constitution grants 25% of seats to the Tatmadaw, it is probable they will remain in control.

Furthermore, the contours of the civil war have changed drastically. After the 2021 coup, it seemed like the resistance forces were gaining influence and territory, but recent counter-attacks by the Tatmadaw have altered the scenario. Multiple towns, such as Nawngkhio and Mobye, as well as towns in the Sagaing region, have been retaken by the military. This will have repercussions on India’s border states. Porous as they are, the refugee influx will remain constant.

To add to the emerging complex dynamics, the presence of international players in India’s backyard may lead to further conflicts. However, while India should closely monitor developments in Myanmar, it must also recognise that Myanmar is not easily dominated by China. India arguably shares more goodwill with the military junta, the NUG, and some EAOs than China ever will.

While China may manoeuvre strategically across faultlines in Myanmar, the reality remains that China and the Chinese do not enjoy the same level of goodwill as Indians do in Myanmar. The Chinese are perceived as purely transactional. In an interview[10] given to Associated Press, Richard Horsey of the International Crisis Group said, “There is a deep well of anti-Chinese sentiment in Myanmar, particularly in the military, and Min Aung Hlaing is known to harbour particularly strong anti-Chinese views. I don’t think China really cares whether it is a military regime or some other type of government in Myanmar. The main issue with the regime, in Beijing’s view, is that it is headed by someone they distrust and dislike, and who they see as fundamentally incompetent.”

However, with anxieties increasing about China’s presence in Myanmar, India could respond to situations more skillfully. For instance, China is concerned about its assets in Myanmar, and to that end, it has introduced the Joint Security Venture Company (JSVC) initiative, whereby international companies can bring their own security to protect their assets. It is reported that there are over 500 Chinese nationals in Rakhine State. India could take similar steps to safeguard its Kaladan Multimodal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP). India’s best strategy is to engage with stakeholders and defend its own interests in Myanmar while providing all necessary humanitarian aid and leveraging the existing goodwill across the spectrum.

Although India’s soft power remains strong, mainly through its Buddhist connections, relying on it alone is unwise. Myanmar is likely to attract many international players competing for influence. Furthermore, the US and China may contend through Myanmar, potentially affecting India as well. Therefore, India should start strategically building strong relationships with local communities along its northeastern borders. The locals need medical aid, higher education, and other essentials. India can help by fostering a generation of Myanmarese who feel a connection to India. This involves providing basic medical support and equipment to states like Chin and Rakhine. Additionally, India can make special arrangements for conflict-affected students to study there.

For border security, it is crucial to spread accurate information to locals on both sides. There is widespread anxiety caused by rumours that the borders will be completely shut down on both ends. The Indian government’s policy should be clarified and must reassure those who legitimately trade through border haats or have family ties across the border.

The mesh wire fencing in the “Hybrid Fencing” pilot project, as observed in some areas near Pangsau Pass in the northeast, may not be adequate. There are risks of misuse. However, the electronic surveillance system is a welcome development. It is crucial that tracking and biometrics of all individuals entering are made compulsory to prevent any illegal infiltration. Refugees seeking temporary shelter must be registered.

Finally, India must strengthen its engagement with Myanmar at all levels. The more foresighted India is at this stage, the more secure its northeastern borders will become in the future. Policymakers, civilians, NGOs, scholars, religious groups, and the military must work together systematically. Myanmar is crucial for regional stability, and if India aims to maintain stability in its vicinity, it must act as a stakeholder. Although India has shown a mature diplomatic approach towards Myanmar so far, the unpredictable nature of the conflict there means that even elections might not resolve the issues. Therefore, India should develop a long-term strategic plan and engage accordingly.

Author Brief Bio: Rami Niranjan Desai is an author, anthropologist and researcher with subject expertise in the north east region of India and India’s neighborhood. She has studied at King’s College, London where she received her degrees in Anthropology of religion and Theology. Rami has spent over two decades studying insurgency, ethnic armed organisations, religion and identity issues. Her vast repository of work is based on her groundbreaking fieldwork over the years in the northeast region and in India’s neighborhood such as Myanmar. She is also well known for her research and analysis and is invited regularly by private and government organisations as a subject expert. She has also collaborated and published books on various occasions with organisations and universities such as Manipur University and Indira Gandhi National Tribal University. She regularly writes for various journals and national publications such as India Today, Open Magazine and has a weekly column called “Ramification” in Firstpost. She is also a regular television panelist appearing on all major English and Hindi news channels. As Distinguished Fellow at India Foundation she focusses on current affairs, the northeast region of India and the neighbourhood. She also curates India Foundation’s flagship event India Ideas Conclave and podcast Insight while leading other significant initiatives.

References:

[1] The Tatmadaw is referred to the armed forces and the military junta to the governing power held by a council from the Tatmadaw.

[2] Source: https://testbook.com/question-answer/imphal-is-the-capital-of-which-indian-state–602b91a8a8f29940c971bec0

[3] Chinese Envoy in Lashio to Broker Return of Myanmar Military. (2025, April 22). Retrieved from The Irrawaddy: https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/myanmar-china-watch/chinese-envoy-in-lashio-to-broker-return-of-myanmar-military.html

[4] The Billion Dollar Death Trade: The International Arms Networks. (2023). Retrieved from Human Rights Council: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/myanmar/crp-sr-myanmar-2023-05-17.pdf

[5] Thein, H. H. (2022, November 22). China is pouring money into junta-ruled Myanmar to secure a ‘back door’ to the Indian Ocean. Retrieved from Scroll: https://scroll.in/article/1037882/china-is-pouring-money-into-junta-ruled-myanmar-to-secure-a-back-door-to-the-indian-ocean

[6] Desai, R. N. (2024, November 4). From Shared Past to Uncertain Future: India’s Strategic Calculus in a Coup-Stricken Myanmar. Retrieved from India Foundation: https://indiafoundation.in/articles-and-commentaries/from-shared-past-to-uncertain-future-indias-strategic-calculus-in-a-coup-stricken-myanmar/#_ednref1

[7] https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/us-lifts-sanctions-on-myanmar-junta-allies-after-general-praises-trump/article69853784.ece

[8] Desai, R. N. (2023, September 29). The New Great Game. Retrieved from Open Magazine: https://openthemagazine.com/columns/the-new-great-game/

[9] Poling, G. B. (2025, August 1). The Dangerous Allure of Myanmar’s Rare Earths. Retrieved from Centre for Strategic and International Studies: https://www.csis.org/analysis/dangerous-allure-myanmars-rare-earths

[10] Peck, G. (2024, August 14). China’s foreign minister meets with Myanmar’s military boss as civil war strains their relations. Retrieved from APnews: https://apnews.com/article/myanmar-china-foreign-minister-civil-war-277613b65eae72e7e1dbd442232b6481