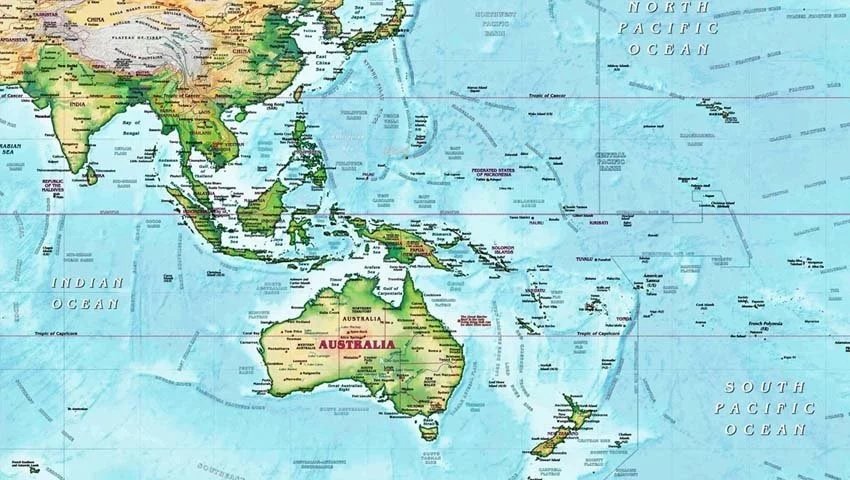

The region in which Australia is located – the Indo-Pacific – is facing the greatest strategic uncertainty since the end of the Second World War. That same region is also engine of the global economy – two thirds of global growth to 2030 will come from the Indo-Pacific.1

Much of this economic growth will have an Indian Ocean dimension. Within the next decade, the world’s top five economies (in purchasing power parity terms) will include two major Indian Ocean states – India and Indonesia.2 The Indian Ocean itself hosts more than half the world’s container traffic, as well as critical infrastructure such as ports and undersea cables, and sea lines of communication vital to global energy trade.3

In other words, a resilient Indian Ocean region matters enormously to the world and it matters to Australia. As a nation that sits astride both the Pacific and the Indian Oceans, and whose western shores cover nearly the entire Eastern boundary of the Indian Ocean, Australia has a major stake in the peace, prosperity, and resilience of the Indian Ocean region.

This paper highlights four areas of strength and strategic interest where Australia can help contribute to the resilience of the Indian Ocean region:

- Advocating for strong regional identity and collaboration

- Promoting economic integration for regional benefit

- Leading future energy partnerships

- Securing regional peace and prosperity

- Stepping up in future challenges and opportunities

A Region that Matters – Building an Indo-Pacific Identity

With just 25 million inhabitants and located far from many of its markets, regional partnerships and collaboration have always been part of Australia’s world view. Australia has played an especially important role in building global understanding of the importance of the Indian Ocean region. This work started with advocacy, first for the idea of an Asia-Pacific, and then subsequently the concept of an Indo-Pacific.

Neither of these concepts – or the collaboration that has emerged from them – were guaranteed. As recently as the 1980s, Australia was considered part of a vaguely defined Oceania. But as both North and Southeast Asian economies grew, bringing more foreign direct investment, Australia and others like Japan and Korea recognised the need for better ways to describe the region, and better ways to collaborate within it.

Australia was at the forefront of efforts to institutionalise the concept of the Asia-Pacific, including through establishment of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Organisation (APEC – an Australian initiative proposed by former prime minister Bob Hawke in Seoul in 1989), the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) security dialogue in 1994 and the East Asia Summit (EAS) in 2005.

But in recent years, it became clear that the Asia-Pacific concept was missing something important – India, and South Asia more broadly. Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was the first world leader to articulate an Indo-Pacific strategy. He debuted the concept in his landmark speech – ‘The Confluence of the Two Seas’ – made to the Indian Parliament in 2007.4 Subsequently his government released a “Free and Open Indo- Pacific” Strategy in 2016.

Australia was an early adopter of this idea – using it in the 2013 Defence White Paper, as the organizing construct in its 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, and most recently in its 2023 Defence Strategic Review. We were also a founding member of the only regional organisation that seeks to promote a specifically Indian Ocean identity – the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

There is increasingly no question that for Australia, the Indian Ocean looms large. Just as importantly, the Indian Ocean looms large for other partners as well. The US changed the name of its Pacific Command to the “Indo-Pacific Command” (INDOPACOM) in 2018 and released Indo-Pacific Strategies under both the Trump and Biden administrations. The EU announced in 2021 its own Indo-Pacific Strategy, as did the UK (termed a “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific). India, Indonesia, Vietnam, ASEAN, the Indian Ocean Rim Association, and many others all have some version of an Indo-Pacific strategy, vision, or construct embedded in their thinking.

Encouraging Economic Integration for a Prosperous Indian Ocean

The idea of the Indo-Pacific has helped encourage a sense of common objectives and interests across the region. But reaching those objectives requires collaboration, including through economic integration. This is something that’s still missing from the Indian Ocean region.

Australia has experience to share, with a solid track record of advocating for “mega-regional” trade agreements within Asia. Two examples of such “mega-regional” trade agreements stand out.

The first example is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP – traversing the entire Pacific Rim). Originally conceived as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the US’ withdrawal threatened the agreement’s survival. But in 2017, Australia – together with Japan – revived negotiations, with the CPTPP signed by all eleven remaining members only a year later.

The second example is that of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP), for which Australia was the driving force. Taking in the region from Australia northward to Japan, RCEP is the world’s largest trading bloc, accounting for almost half the world’ population, over 30 percent of global GDP, and over a quarter of global exports. It could have been bigger – but India withdrew from negotiations in 2019.

These two agreements provide some salutary lessons.

First, not only does Australia have a strong commitment to economic integration as a way of building Indo-Pacific prosperity, but it can also step into regional leadership roles when the US falters.

Second, India’s absence from Indo-Pacific economic architecture has limited the potential of these regional trade agreements.

With India set to be the world’s third biggest economy, any efforts to promote Indian Ocean economic integration must include India. While there’s still much work to do, India’s partial participation in the new US Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (alongside participation from other regional countries including Australia, Japan and ASEAN) holds the potential to closer bind the Indian Ocean with the Pacific.

Australia’s Role in a Resilient Indian Ocean Energy Future

Along with greater economic integration, the Indian Ocean needs its own energy security and is pivotal to the energy security of others.

The Indian Ocean’s importance to traditional global energy security is well established. It is home to 40 per cent of the world’s offshore oil production (which includes significant reserves of liquified natural gas off the coast of Western Australia),5 as well as about 80 per cent of the world’s maritime oil trade traverses the Indian Ocean.6 It’s especially important for China, which relies on shipping lanes through the Indian Ocean and the Malacca Straits chokepoint for a majority of its imports.7

As the world transitions to clean energy, Australia – and therefore the Indian Ocean – will remain important. The visit of Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio to Perth Western Australia in October of 2022 included a focus on Australia’s role as a source of rare earth elements, lithium, other critical materials, as well as hydrogen, making it clear that the road to future energy for the Indo-Pacific runs through Australia.

The largest opportunity is likely to be in ‘critical minerals’, and associated value chains such as batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) and grid storage. The International Energy Agency estimates critical minerals production for clean energy must at least quadruple to 28 million tonnes per annum by 2040.8 The challenge is that just a few countries dominate extraction of key minerals. China controls most processing and manufacturing activity – for example it produces more than 90 per cent of the rare earths used in semiconductors and magnets.

As the supply chain disruptions of COVID showed so clearly, reducing market concentration – in any sector – is a good thing. It’s even more important in such a critical sector as clean energy. Australia of course will be a key partner – it already produces about half the world’s lithium. It’s also a leading supplier of other minerals needed for the energy transition, including bauxite, cobalt, rare earths, vanadium, graphite, and nickel.9

But the challenges of these complex energy supply chains can’t be solved by one country alone. Australia might have world-leading natural resources, but it will need to work with countries – including in the Indian Ocean – to develop new processing pipelines and off take agreements.

India for example is seeking to become a major rival to China in clean energy manufacturing. The Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement of 2022 eliminated tariffs on most Australian critical minerals.10 The India-Australia Critical Minerals Investment Partnership was also unveiled in 2023.11

Indonesia is also looking to Australia as a potential source of lithium, to complement its own vast nickel reserves and support its aspirations to become a major EV manufacturer.12

Australia and other Indian Ocean countries can work more closely together to build up trusted and resilient critical minerals value chains and deliver an equitable share of the economic returns. Work through regional institutions could complement bilateral partnerships. The Quad has a dedicated critical minerals stream.13 So too does the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity.14

Indian Ocean Security Partner

Australia’s national Defence Strategic Review, published in late April, identified the Indian Ocean as a key strategic area, with the Northeast Indian Ocean part of the primary area of military interest for Australia’s National Defence. It acknowledged that Australia’s Defence Cooperation Program needs to expand into the Indian Ocean, its relationship and cooperation with India and Japan needs to grow, and the importance of investment in regional architecture for security outcomes.

Australia has had a longstanding role in the security of the Indian Ocean. Its dedication to regional stability has taken shape through various security avenues, including:

- The considerable projection capability of its military, expected to grow under the trilateral Australia-U.K.-U.S. AUKUS agreement.

- The Australian Defence Force’s maritime surveillance patrols in the Northern Indian Ocean.

- Its treaty alliance with the United States, which has helped to uphold global commons as well as secure shipping and sea lanes of communication, and which will certainly be enhanced by the AUKUS agreement.

- The ambitious agenda of the Quad grouping of Australia, India, Japan and the United States, which will be further highlighted in late May when the leaders of these four countries meet again in Sydney.

The various initiatives of both AUKUS and the Quad are directly related to the resilient future envision by the annual Indian Ocean conference and highlight Australia’s commitment to both traditional and non-traditional areas of security.

Facing Future Challenges Together

The global challenges with which the world is now grappling traverse the Indian and Pacific Oceans – challenges like climate change, maritime insecurity, the rise of China and its use of economic coercion against Australia and other partners, great power rivalry, terrorism, natural disasters and environmental insecurity. The Asia-Pacific construct no longer captures these interlinked issues, countries, or Australia’s interests. That is in part how the concept of the Indo- Pacific started to gain currency.

As political leaders throughout the Indian Ocean gather to discuss the myriad challenges facing the region including climate change, security, infrastructure and more, it will become increasingly apparent that the technological and industrial responses to many of these challenges will require a cooperative approach to ensure that we have the necessary materials to enable such responses.

Australia will continue to take its place in the Indian Ocean Region tackling the substantial shared existing challenges and emerging threats facing the region. We know that regional identity matters, and the considerable progress to date means there is a firm foundation for future collaboration.

Authors’ Brief Bio: Prof. Gordon Flake is the Director; Chief Executive Officer, Perth USAsia Centre, The University of Western Australia, Dr. Lisa Cluett, External Relations Director, Perth USAsia Centre and Dr. Kate O’Shaughnessy, Research Director, Perth USAsia Centre

Note: This article was published by India Foundation in the Indian Ocean Conference 2023 Theme Paper Booklet.

References:

- “The Indo-Pacific will create opportunity”, Chapter two: A Contested World, 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/minisite/static/4ca0813c-585e-4fe1-86eb-de665e65001a/fpwhitepaper/foreign-policy-white-paper/chapter-two-contested-world/indo-pacific-will-create-opportunity.html.

- Ibid.

- “Australia and the Indian Ocean Region”, Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, https://www.dfat.gov.au/international-relations/regional-architecture/indian-ocean/Pages/indian-ocean-region.

- “Confluence of the Two Seas”, Speech by E. Mr Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan at the Parliament of the Republic of India, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html.

- “Australia and the Indian Ocean Region”, Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, https://www.dfat.gov.au/international-relations/regional-architecture/indian-ocean/Pages/indian-ocean-region.

- “The Indian Ocean Region May Soon Play a Lead Role in World Affairs”, The Wire, January 16, 2019, https://thewire.in/world/the-indian-ocean-region-may-soon-play-a-lead-role-in-world-affairs.

- Giulio Gubert. “Myanmar and the Belt and Road Initiative. A solution to China’s Malacca Dilemma?”, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, June 04, 2019, https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/gia/article/myanmar-and-the-belt-and-road-initiative.-a-solution-to-china’s-malacca-dilemma; Paweł Paszak. “China and the ‘Malacca Dilemma’”, China Monitor, February 28, 2021, https://warsawinstitute.org/china-malacca-dilemma/.

- “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions”, International Energy Agency, May 2021, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions.

- “World Rankings”, Australian Government: Geoscience Australia, https://www.ga.gov.au/digital-publication/aimr2022/world-rankings.

- “Australia-India ECTA benefits for the Australian critical minerals and resources sectors”, Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/australia-india-ecta/outcomes/australia-india-ecta-benefits-australian-critical-minerals-and-resources-sectors.

- “Milestone in India and Australia critical minerals investment partnership”, Australian Government: Department of Industry, Science and Resources, https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/king/media-releases/milestone-india-and-australia-critical-minerals-investment-partnership.

- Emma Connors. “Indonesia lures EV makers in race to secure nickel supplies”, Australian Financial Review, April 23, 2023, https://www.afr.com/world/asia/indonesia-lures-ev-carmakers-in-race-to-secure-nickel-supplies-20230421-p5d2f4.

- Tom McIlroy, “Australia rallies Quad on critical minerals security”, Australian Financial Review, July 13, 2022, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/australia-rallies-quad-on-critical-minerals-security-20220713-p5b17r.

- “Speech to the Future Facing Commodities Conference, Singapore”, Australian Government: Department of Industry, Science and Resources, April 05, 2023, https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/king/speeches/speech-future-facing-commodities-conference-singapore.