India Foundation hosted a farewell reception for H. E. Naor Gilon, Outgoing Ambassador of Israel to India, on July 19, 2024. In his three-year tenure as the Ambassador of Israel to India, he has actively promoted and assisted in maintaining the strong ties between the two countries. Several eminent dignitaries attended the event and conveyed their best wishes to the outgoing ambassador.

Defining ASEAN centrality in the Indo-Pacific

India Foundation hosted a roundtable discussion on “Defining ASEAN centrality in the Indo-Pacific” with a delegation from S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies of Singapore on July 12, 2024 in New Delhi. The discussions were led by Amb Ong Keng Yong, Executive Deputy Chairman, RSIS, Singapore and Vice Adm Shekhar Sinha, Chairman, Board of Trustees, India Foundation. The session was also addressed by Amb TCA Raghavan, Former Ambassador of India to Singapore and Dr Sinderpal Singh of RSIS.

The discussions centred around the strategic importance of ASEAN, regional challenges, and the implications of China’s actions in the region. The importance of ASEAN’s strategic location, particularly with regards to the South China Sea, was emphasized due to its geopolitical and economic significance. ASEAN countries, being some of the most impacted by regional tensions, play a crucial role in addressing these challenges. The discussion highlighted China’s aggressive behaviour concerning its territorial claims over Taiwan, the Senkaku Islands, and the Paracel Islands.

In their opening remarks, Amb Ong and Adm Sinha touched upon various facets of ASEAN’s centrality to the Indo-Pacific. They stressed on the necessity for ASEAN to respond collectively to regional challenges and emphasized on the emergence of India as a key partner. The strong bilateral relations between India and ASEAN countries were also acknowledged as crucial for fostering regional cooperation.

The scope of discussions further included ASEAN’s pillars of engagement with the Indo-Pacific, differences between various Southeast Asian states and individual approaches to the Indo-Pacific and how Southeast Asia is possibly negotiating this vision of the Indo-Pacific.

Tibet Talks – 7 – The Resolve Tibet Act: Legal and Humanitarian Perspectives

India Foundation organized the seventh session of the Round-Table Discussions in the ongoing “Tibet Talks” series. The topic for this session was “The Resolve Tibet Act: Legal and Humanitarian Perspectives”. The session was addressed by Dr Tenzin Dorjee, Senior Researcher and Strategist, Tibet Action Institute. The Round-Table Discussion took place on 9 July 2024 (Tuesday) at the India Foundation office, with the session chaired by former Ambassador Dilip Sinha.

To start the discussion, Dr Dorjee emphasized the importance of the Resolve Tibet Act as it symbolized a change in the United States’ policy towards Tibet, especially with the Act explicitly stating that the U.S never recognized Tibet historically as a part of China. This shift in tone displays the U.S’ renewed focus on advocating for the collective right of self-determination instead of purely individual rights for the people of Tibet. Additionally, Dr Dorjee highlighted his own personal experiences: growing up in India, attending Tibetan schools, and living in the United States. He then underscores how three generations of Tibetans living in exile have maintained the Tibetan culture, language, and lifestyle that continues to flourish in India, given the country’s commitment towards protecting the government in exile while providing Tibetans with a space to live and preserve their culture in peace. Furthermore, Dr Dorjee details the importance of the Act’s passage for Tibet’s status on the world stage. With the Act invoking the idea of self-determination for the people of Tibet, the U.S is attempting to shift the mainstream perspective from a diplomatic to an international law point of view.

To conclude, Mr. Dorjee emphasizes how the Resolve Tibet Act has laid the groundwork for new opportunities to further expand the movement to free Tibet.

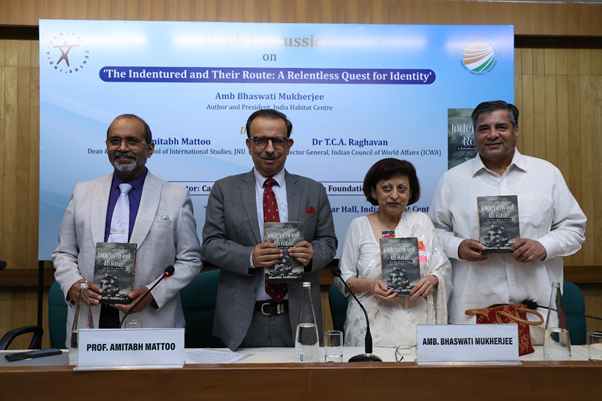

Book Discussion on ‘The Indentured and Their Route: A Relentless Quest for Identity’

India Foundation, in collaboration with India Habitat Centre, organised a book discussion on ‘The Indentured and Their Route: A Relentless Quest for Identity’, authored by Amb Bhaswati Mukherjee, President, India Habitat Centre and Ambassador of India to the Netherlands (2010-2013) at Gulmohar Hall, India Habitat Centre, on July 02, 2024. The event began with the initial remarks by Captain Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation, who introduced the book to the audience and later moderated the discussions. Prof Amitabh Mattoo, Dean & Professor, School of International Studies, JNU and Dr T.C.A. Raghavan, Former Director General, Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) discussed the book with the author.

Ambassador Mukherjee eloquently highlighted the compelling narrative of this book, which sheds light on the heart-breaking journey of Indian indentured labourers who were compelled to leave their homeland for distant lands like the West Indies, Mauritius, Suriname, Reunion, and Fiji. Driven by desperation due to famine, poverty, and oppressive conditions in India, these individuals were lured by false promises that ultimately led to forced labour and significant loss of heritage.

Professor Mattoo praised the author, noting that this book is a breath of fresh air as it delves into an important area with elegance, drawing from diverse sources and imbued with poetic language. This book fearlessly challenges conventional wisdom and offers a novel perspective on indentured labour and their ancestral connection with their Indian homeland.

Dr. Raghavan shed light on the content of the book, stating that the book provides numerous examples, such as Fiji, where the identities of former indentured servants were on the brink of being systematically erased. These individuals, tied to colonial legacies, were compelled to sever their connections to their roots and histories. The book offers a profound insight into the enduring impact of indentured slavery, a practice often viewed as a temporary phase in human history, yet persisted for 70-80 years. He found the book to be deeply reflective and thought-provoking, challenging readers to consider the complexities of legacy and urging a re-evaluation of how we perceive diaspora communities today. The discussion was followed by Q & A session where several questions related to the book and the author were asked by the audience.

Rājadharma: The Bhāratīya Notion of Welfare State

Since ancient times, civilisations have recognised the need to regulate individual behaviour and social conduct to prevent anarchy and chaos. In the Bhāratīya Paraṁparā, this regulation found expression in the concept of Rājadharmạ, or the duties of a ruler, which emphasised the integration of temporal power with spiritual wisdom for the collective welfare. Ancient Bhāratīya thinkers, guided by practical concerns rather than abstract theorisation, envisioned political governance to promote universal well-being. They emphasised the importance of a ruler adhering to the principles of dharma (duty) and śāsana (regulation) to ensure peace, progress, and prosperity for all beings. The ideal of Rājadharmạ, exemplified by figures like Śrī Rāma, emphasises the holistic welfare of the entire cosmos, transcending narrow notions of material prosperity. It stresses the symbiosis of political power with spiritual wisdom, wherein governance is not merely about enforcing laws but also about upholding moral values and accountability.

Through a synthesis of dharma and śāsana, a ruler is expected to serve and protect the people selflessly (niṣkāmabhāva), ensuring their happiness and well-being (sarvabhūtahita” and “lokasaṅgraha). In modern times, the concept of Rājadharmạ remains relevant as societies strive for inclusive development and universal welfare. By embracing its principles of duty, responsibility, and spiritual wisdom, nations can aspire towards a more just, equitable, and harmonious world order. This research article aims to explore the concept of Rājadharmạ, or the duties of a ruler, within the Bhāratīya tradition, highlighting its integration of temporal power with spiritual wisdom for collective welfare. Through an examination of ancient Bhāratīya thinkers, it elucidates their emphasis on practical governance rooted in principles of dharma (duty) and śāsana (regulation) to ensure peace, progress, and prosperity for all beings.

Since the dawn of civilisation, there has been a recognised need to regulate human social conduct alongside individual behaviour. Humanity, both cooperative and selfish by nature, has grappled with instincts of cooperation and conflict, necessitating the establishment of order to prevent anarchy (arājakāta) and a “rule of the jungle” (matsyanyāya). For the preservation and advancement (yoga-kṣema) of communal life, social and political governance becomes imperative to prescribe and enforce order. Ancient Indian seers and sages envisioned order at the core of reality, known as ‘ṛta’, finding its expression in temporal power as ‘an authority’ (law) and ‘in authority’ (those who wield power). This temporal power (kṣatra tejā) was seen as subordinate to and tempered by spiritual power (Brahma tejā), ensuring its purpose served the greater good. In general, power (Śakti) must be imbued with wisdom (Śiva) for benevolent outcomes. Political governance, prone to perversion and corruption due to its overpowering nature, requires spiritual discipline, hence termed ‘Rājadharma’ or ‘Dandanīti’. These terms reflect the spiritual orientation of political power, engineered for universal peace, prosperity, and well-being.

Lord Rama, exemplified the exercise of political power in a spiritual manner, projecting his rule as an ideal of a welfare state, termed Rāmarājya, a Sarvodaya state. The suffix ‘sarva’ extends beyond human society to encompass the welfare of the entire cosmos, including animals, forests, and rivers. The underlying principle is that the universe is a habitat for all existences, animate and inanimate, sharing the same divinity and living together with mutual care and sharing. In good governance, everyone is treated as having both intrinsic worth and instrumental value, viewed not solely as an end or means but as both simultaneously. In communal life, coexistence and interdependence prevail, fostering reciprocity and mutual support among all elements of the cosmos, encapsulating the ideal pursued in an ideal state, thereby realising a genuine welfare state.

The ancient Indian thinkers on political affairs were primarily driven by practical governance concerns, eschewing abstract theorisation in their reflections. Neither in ethics nor in politics did they indulge in pure speculation; instead, they meticulously discussed the minutest details of state administration for the well-being of all beings (prajā). Various treatises, apart from the well-known epics and scriptures like Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, Purāṇas, and Dharmaśāstras, delve into polity and state administration, with references to now-extinct Arthaśāstra treatises. Unlike modern trends advocating rigid theories or ‘isms’, ancient Indian literature lacks such formulations. Instead, it offers subtle discussions on practical aspects of governance, aiming to guide rulers in day-to-day administration after providing them with education and training. These discussions are based on concrete experiences and pragmatic considerations, avoiding empty generalisations and pure abstractions.

Indian thinkers recognised the importance of bridging the gap between theory and practice, emphasising that the ideal must be achievable from actual experiences. This ideal, termed puruṣārtha, integrates the end (sādhya), means (sādhana), and modalities (itikartavyatās), ensuring that the end is beneficial, the means are conducive, and the modalities are accessible. In this approach, theory is not divorced from practice but interwoven with it in a dialectical relationship. Ancient Indian literature emphasised practical wisdom over abstract theory, employing empirical observation, analysis, and deduction methods and leading to the development of treatises on politics rather than political science.

While classical Bhāratīya political thought does not explicitly present a theory of the welfare state, it is rich in welfare ideals that serve as guiding principles for governance. The literature is abundant with profound concepts emphasising collective well-being, permeating political and cosmic organisation. These principles, integral to every ruler’s mandate, suggest a holistic approach to welfare that transcends mere governance, encompassing human existence and cosmic harmony. This comprehensive approach to welfare, deeply ingrained in ancient Indian political thought, is truly inspiring.

The entire Bhāratīya thought, across all its domains of reflection, is rooted in the fundamental belief that the cosmos is a divine manifestation with an inherent purpose and value. From ancient texts like the Puruṣa sūkta of the Ṛgveda to modern thinkers such as Vivekananda, Śrī Aurobindo, B.G. Tilak, and Mahatma Gandhi, this idea of a divine purpose permeates the philosophy. It is believed that the universe exists, sustains, and culminates in a state of supreme well-being and bliss, often referred to as Amṛtatva, Brahmatva, mokṣa, or nirvāṇa. All human endeavours, organisational structures, and the cosmic process itself are directed towards this end. Concepts like ‘svasti’ and ‘śivam’ signify the pursuit of universal well-being and bliss. Additionally, concepts like ‘śubha’, ‘sukha’, ‘śānti’, and ‘maṅgala’ express the ideals of goodness, happiness, peace, and auspiciousness inherent in Bhāratīya philosophy. The Vedic seers emphasised the well-being of the entire cosmos, as evidenced by the famous ‘Śāntipatha’ from the Yajurveda Saṃhitā (36.17, Vājasaneyi Madhyadina śukla), which underscores the holistic welfare of all beings:

“aum dyauḥ śāntir antarikṣa śāntiḥ pṛthivī śāntir āpaḥ śāntir auṣadhayaḥ śāntiḥ vanaspatayaḥ śāntiḥ viśvedevāḥ śāntiḥ brahma śāntiḥ sarva śāntiḥ śāntir eva śāntiḥ samā śāntiḥ reḍhi”[i]

(May there be peace and prosperity in the outer and inner space, on earth, in the waters, in the life-giving vegetable kingdom, in plants and trees, in the cosmos, in the entire reality, everywhere and at all times. May there be peace and prosperity. Peace and prosperity alone (never otherwise). May everyone attain and experience peace and prosperity.)

Every human activity- both individual and collective- has to be geared to realise this goal of peace, prosperity and perfection. The Ṛgveda (V.51.15) says, “ Svasti pantham anucarema sūryācandramasāviva.” All puruṣārthas (conscious and wilful human efforts) and all prayers and propitiations to supra-human agencies aim at this. There is a tacit realisation of inadequacy of human effort and the need for supra-human support or divine help. “Sanno kuru prajābhyah” (Let there be welfare of the entire creation), beseeches the Vedic seer. Even though the Sramana tradition opposed this mind-set, the Indian psyche remained unaffected. The point is that since the entire cosmos has inevitable and natural teleological orientation there is a deontological injunctive-ness in social, moral and political spheres to make a conscious attempt at pursuance of the good and the right, to follow the path of ‘Ṛta.’ The pursuit of this ideal was a collective endeavor, evident in countless prayers for unity and shared well-being found throughout Bhāratīya literature, particularly in the Vedas. The thinkers of this land prioritized the welfare of the entire cosmos, shaping human behavior, social structures, and state activities towards the common good and prosperity. The ideal of all thought and conduct was:

sarvo vai tatra jīvati gaurasvaḥ puruṣaḥ paśuḥ|

yatredaṁ brahma kriyate paridhirjīvanāya kam||[ii]

(May humans, animals, birds and all other existences coexist in peace and there is room for every life.)

It is to be noted that the guiding principle of the statecraft and political organisation and administration has to be welfare of the people and well-being of the cosmos and there is no incompatibility between the two. This was the ideal of a state depicted in the Rāmāyaṇa and practiced by Rāma, the King of Ayodhya. Even the Śrīmadbhāgvatam states:

na aham kāṅkṣye rājyam na svargam apunarbhavam

kāṅkṣye duḥkha tr̥ptānām prāṇinām artanāśanam.

(I do not desire kingdom, nor heaven, nor even liberation from rebirth.

What I desire is the cessation of suffering for all living creatures.)

There can be no better ideal of welfare state than the one propounded here. The word ‘rājan’ in one of its etymological meanings stands for a ruler who pleases the people and makes them happy. Another word ‘nṛpa’, a synonym of it, conveys the idea of the ruler as a protector and sustainer of people. Kauṭilya extends this idea covering the entire world. He points out that a ruler has to be well versed in Arthaśāstra apart from other background studies and the objective of Arthaśāstra is to deal with protection and well-being of the entire universe. He writes, “Pr̥thivyā labharthe palane ca yavanty arthaśāstrāṇi purvācāryaiḥ prasthāpitāni prayatnena samhṛtya ekaṁ idam arthaśāstram kṛtam.” He explicitly maintains that in the happiness of people lies the happiness of the ruler and in what is beneficial to the people lays his own benefit. To quote:

praja sukhe sukham rājñaḥ, prajānām ca hite hitam|

nātma priye hitam rājñaḥ, prajānām tu priyam hitam||[iii]

(In the happiness of the people consists the happiness of the ruler, and in what is beneficial to the people, his own benefit. What is dear to him as an individual is not really beneficial to him as a ruler. What is dear to the people is really beneficial to him)

A ruler has to be the preserver of order both temporal and spiritual. He is therefore referred to as ‘Dharmagopta’. He is not the creator of the order but only propagator (dharma pravartaka). He has to uphold the law and order and therefore he is called ‘dandadhārta’. This he has to do for peace, progress and prosperity of the people in just and fair manner. He has political power that acquires legitimacy only in so far as it promotes human happiness and enriches life. Manusmṛti (VIII.14) states:

dandah śāstī prajāḥ sarvāḥ, danda eva abhi rakṣati,|

dandah suptesu jagarti, dandah dharma vidur budhāḥ||[iv]

(It is public order that regulates people. It protects and secures them. It keeps awake in the midst of slumbering. The wise regard it and dharma as one and the same)

Kautilya also maintains that daṅda is needed to promote proper and equitable distribution of social gains, and for material prosperity and spiritual enhancement. He writes, “Ānvīkṣikī trayī vartanam yoga-kṣema sādhano dandah. Tasya nitir dandanitiḥ. Alabdha-labhārtha labdha-parirakṣinī rakṣitāvivardhinī vr̥ddhasya tīrthāsu pratipadini.”[v]

The concepts of yoga-kṣema are of particular significance in this context. They stand for preservation and furtherance of natural resources and also their just and equitable distribution. It is the duty of a state to ensure this. It is noteworthy that this is a forerunner of the idea of ‘Sarvodaya.’

The Indian treatises on polity are full of need for danda and also for the regulations for the dandadhṛta. For smooth, efficient and planned functioning of any organisation there is a need for norm-prescription, norm-adherence, norm-enforcement and punitive measures for norm-violation. So, to ensure norm-conformity there is a need for an authority of law and a person who is in authority. An authority is impersonal law but the person in authority is the ruler, a person or a body of persons, who execute and ensure law-abidance. ‘An authority’ is autonomous but a person ‘in authority’ is subject to rules and regulations. ‘An authority’ has intrinsic worth but ‘a person in authority’ has instrumental value to rule out anarchy and to ensure peace and justice. He is appointed for the sake of maintenance of law and order. For this he may build up institutions and introduce systems. But in all this he is duty-bound and therefore he has to abide by some rules and regulations. The ‘rāja’ also has a dharma, a law-abiding status. He must know his dharma and must have a will and ability to abide by it. In the Mahābhārata we have a very apt, telling and succinct account of this idea in the oath to be administered to a ruler at the time of his appointment when he is advised to protect the people lawfully and never to act in an arbitrary manner. He is required to take a solemn vow to observe dharma and to make people observe dharma in a free and fearless manner. The wording of the oath is as under:

pratijñāṁ ca varohasva manasā karmāṇā girā|

palayiṣyāmy ahaṁ bhāumam brahmaiti eva ca sakṛta||

yaś ca tatra dharma ityukto dandanīti vyapāśrayaḥ|

tamasaṅkam kariṣyāmi svavāso na kadācana||[vi]

(Make a promise, and with your mind, deeds, and words, I shall protect the earth as per my oath. Wherever the duty of righteousness and the policy of punishment are in place, I shall root out darkness. I shall never reside in a place where there is disgrace.)

Dharma has cosmic sphere of operation. It sustains the entire cosmos and all beings. It has both constitutive and regulative roles. It constitutes the life-force and sustaining power. The entire cosmos is dharma-bound and therefore the ruler also is dharma-bound. Rājadharma is double-edged. It puts desirable restraints on the public so as to enable them to realise their puruṣārthas but at the same time it makes the person in authority subject to restraints. The person in authority is not to enjoy power and privileges but to discharge duties and responsibilities. He cannot be immune to accountability and oblivious of his obligations.

Śukrācarya, a great political thinker of yore, maintains that the ruler is both a servant and a master of the people. Therefore, he has to protect the people as master by virtue of law and serve them by virtue of his wages. He writes:

svabhāga-bhṛtya dāsyatvam prajānām ca nṛpakṛtaḥ|

brahmānā svamirūpastu palanārtham hi sarvadā||[vii]

(The ruler serves and protects all living creatures in his country. However, he should always act as a Brahmin)

There is not only an insistence on proper education and training of the ruler, but it was also made mandatory that the state power (kṣatra teja) should be seasoned and tempered by spiritual power (Brahma Teja). To ensure that the state acts for the welfare of the people and to eliminate the despotic behaviour of a ruler, In Indian thought, politics was never devoid of dharma and was treated as a means to general well-being. As stated earlier, Rajadharma is double-edged. It puts desirable restraints on people’s behaviour, but at the same time, it makes the rulers responsible and accountable by restraining them. A symbiosis of dharma and śāsana is the cornerstone of a welfare state. No one can be a good ruler without being well-trained in dharma and śāsana. There cannot be a separation of politics and spirituality. Political power acquires moral legitimacy only when it is seasoned with spirituality. Only then can it serve its avowed goal of cosmic well-being. Genuine welfare is not the material well-being of a particular section of human society but the holistic welfare of the entire cosmos. It is spiritual welfarism that includes and also transcends material welfarism. This is the true meaning of raja dharma, which may be taken as a concept, theory, viewpoint, or course of action, but in whatever form it is understood, it has great potential for universal good.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that from the dawn of civilisation, a need arose to regulate human social conduct alongside individual behaviour. The human inclination toward cooperation and conflict necessitated the establishment of order to prevent anarchy and chaos. Social and political governance became imperative to prescribe and enforce order for the preservation and advancement (yoga-kṣema) of collective life.

The concept of Rajadharma, or the duty of a ruler, has its roots in the ancient Bhāratīya civilisation. The seers of that time envisioned a system where temporal power (kṣatra tejā) was subservient to and tempered by spiritual power (Brahma tejā) to serve the desired purpose. This was a response to the overwhelming nature of political governance and its susceptibility to corruption, thus leading to the development of the concept of Rajadharma or Dandanīti.

The legendary Bhāratīya ruler Śrī Rama exemplified political power exercised with spiritual wisdom, portrayed as an ideal of a welfare state in the epic Rāmāyaṇa. Following Mahatma Gandhi, this concept is referred to as Rāmarājya, a Sarvodaya State aimed at the welfare of the entire cosmos. This welfare extends not only to specific sections of human society but encompasses the entirety of existence.

The Bhāratīya treatises on polity emphasise the role of the ruler in upholding Rajadharma. They stress the need for daṅda (punishment) and regulations for its implementation. Smooth governance requires norm prescription, adherence, enforcement, and punitive measures for violations. An authority of law is essential, but the person in authority, typically the ruler, must adhere to rules and regulations. The ruler’s duty, encapsulated in Rajadharma, entails serving as a preserver of order, subject to accountability and obligations.

Rājadharma operates within a cosmic sphere, sustaining the entire cosmos and its beings. It imposes desirable restraints on the public and rulers, emphasising duties and responsibilities over power and privileges. The ruler is viewed as both a servant and a master of the people, entrusted with protecting and serving them.

Furthermore, integrating political power (kṣatratejā) with spiritual wisdom (brahmatejā) ensures genuine welfarism, encompassing the material and spiritual well-being of the cosmos. This holistic approach transcends material welfare to embody spiritual fulfilment and universal harmony. Therefore, the ancient Bhāratīya notion of Rājadharmạ encapsulates the ideals of a welfare state, where principles of duty, responsibility, and spiritual wisdom guide governance. This concept, rooted in pursuing universal good, remains relevant and holds great potential for fostering harmony and prosperity in modern societies.

Author Bio: Dr. Vandana Sharma ‘Diya’ is an Assistant Professor, Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi. She is also a Member of the Central Board of Film Certification, Govt. of India and Fellow with Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla and a Researcher with Kedarnath Dhama, Ministry of Culture. She is a Former Fellow of ICPR, ICSSR, Ministry of Education.

References:

[i] Yajurveda, 36.9

[ii] Atharvaveda 8.2.25

[iii] Arthashastra., 1.19

[iv] Manusmriti.,7.18

[v] Ibid, 1.4

[vi] Mahabharat., 7.58.115-6

[vii] Shukracharyaniti (Here the word Brahmin means the one who is established in Sattvic acts, thoughts, speech and ways of leading his life.)

Interview with Shri M. J. Akbar

Rami Niranjan Desai:

In your journalistic career and also in your role as the Minister of State, External Affairs, Govt of India, you have closely observed India’s relations with the Middle East. While the region has been a priority for India, there is a distinct change now, in India’s dealings with the region. What are the factors that contributed to this change?

You obviously saw the early developments being MOS external affairs on the different relationship building that India, sort of had with the Middle East. Even though the Middle East has been a priority for India, it seems like something changed. Can you take us through what the foreign policy change was and what contributed to this positive relationship that we have with the Middle East today?

MJ Akbar:

Let me start with a question, not an answer, right? What on Earth is the Middle East? I don’t raise it as a semantic question or a kind of peripheral banter; I raise it as a vital element of our understanding of this region. The moment we call it the Middle East, we are not looking at it from the perspective of the region. We are not looking at it from the perspective of Asia or even from the perspective of Africa. We are looking at it from the perspective of the colonial powers, primarily Britain, and then its successor power in the region, America. For them, it is in the middle of their east. If you want to call any region in Asia, the Middle East, then, actually, the only Middle East is India. So first, unless we clear these cobwebs that have been planted upon our brain and into our intellectual DNA by colonialism, we are not going to be able to see reality. Let’s call it West Asia, which is a far better term. It is a term that we have used with great consistency, and I hope that this term will also find genuine currency even in the countries of the region we are addressing.

From the Indian perspective, the most crucial development under Mr. Modi’s prime ministership happened, like most great changes, almost surreptitiously. He redefined the arc of the neighbourhood. He also redefined what a neighbour is—not simply an accident of geography but defined by reach. As an illustration, today, we have, from across India, over a thousand flights to the Gulf every week. And on these flights, it isn’t easy to find a seat!

On the other hand, there is not a single flight to Pakistan. So, who is India’s neighbour? This consciousness that you mustn’t get trapped by geography and that you must rise above geography and see things and create new realities is one of the most significant achievements of Prime Minister Modi, which happened stage by stage, step by step. The starting point was when he became the Prime Minister and visited the UAE, becoming the first prime minister in about 36 years to do so. What was India doing for three and a half decades before that? And even before that, the visits were cursory rather than substantive. Mr Modi has turned it into a substantive relationship. These are all Arab nations, after all. He pulled the Gulf, and Egypt is part of the Gulf. And here again, I’ll offer you a reality that corrects our perspective’s dimensions. It takes less time to reach Dubai from Delhi than it takes to reach Cairo from Dubai. That’s how close we are to the Gulf. And from Mumbai, it is even closer.

That is a change of perspective because Mumbai and Dubai have a vast gulf of water between them. And from there, we went to take the sequence forward, right up to Indonesia. And that’s the arc of the new neighbourhood, which has become one of the most productive elements. It is a very sustained and sustainable relationship, built on the most valuable part of any bilateral or multilateral relationship—the economic welfare benefits to the people. Geopolitically, we broke through a kind of wall constructed between us by a particular neighbour in the name of religion, and this process has been very beneficial to us. From COVID onwards, it began to stutter a little but will revive consciously because the base is too strong. What has been built has already achieved a great deal. And I think we will see a continuation of what has been created for the region’s benefit. Eventually, the world understands that very positive new geopolitics is in play.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

Absolutely. You made some fascinating points. Stability in West Asia is hugely essential for us to continue this engagement. How do you see the conflict between Israel and Hamas playing out. Do you think it will remain limited or in the long run, do you see it becoming a larger issue which can spread to Iran. How do you think India is dealing with it?

MJ Akbar:

A point I missed in my opening remarks was that the most interesting part of Prime Minister Modi’s foreign policy was that this whole bridgehead created with West Asia was not at the expense of our relations with Israel. And it is unique. It is remarkable, and they recognised it. The region accepted India’s outreach because they knew that Prime Minister Modi was not building any relationship that would be hostile to their cause. India is a power. India is a regional power. A regional power has and must have the capability of having relationships across binaries. Regional conflicts do not break our relationships. We have very good relationships with Iran. At that time, Iran was not the closest of friends with the UAE and the Saudis, but we built excellent relations with both and continue to do so. And this has been recognised in the region and is a significant contribution to them and the issue. So, India can create a balance in a challenging region. As far as the conflict goes, let’s score and underscore one fact—flames don’t have a geography.

Just as we speak, Hassan Nasrallah has threatened Cyprus because he says that the IDF—the Israeli Defense Forces, are training in Cyprus for a possible invasion of Lebanon. This war is not going to end so soon. There are many new discordant elements that one hears from within Israel. Recently, the IDF made two important statements. One is that Hamas is not going to be defeated so easily because it is an ideology. It is not simply an army. It’s equivalent: Can you defeat the communist ideology even if you defeat the PLA? So, that’s a very wise position to take. They’re asking for not an end to conflict but a restructuring of war objectives. War objectives are always the most essential elements of war and must be rational. They have to reflect a sense of justice against justified grievance. They cannot become irrational.

Right. And I think these are the difficult questions now bothering the region. Horrific scenes are being played out every day from the Palestinian camps and the tragic death of young people in the Israel Defense Forces—young people on both sides of the conflict. The old never die from the decisions they make. I think India should have a significant role in resolving this crisis.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

You also said there’s no end to this because it’s like an ideology. Hamas is an ideology. Where can India fit in? India also depends on West Asia for its energy requirements. Hence, the stability of this region is hugely important to India. You also said that Prime Minister Modi has navigated in such a way that he enjoys the trust of all parties involved. So what can India do to ensure that there is stability in this region and that its impact on trade and energy flows to India is not hampered?

MJ Akbar:

The trade and energy flows will continue irrespective of the conflict because trade is not one-sided. The energy producers need a market as much as the market needs the energy. So, that is not the top of my concerns. The concerns are really of destruction, where there should be positive construction. What can be created by amity, and I am not even using the term harmony, is far more valuable than what can be achieved by rampant destruction. That’s the lesson of every war because it is essential to remember that we are not in the age of empires. The Age of Empires collapsed with the end of colonialism. I know that neocolonialism has not ended, but colonialism has, and we are in the age of the nation-state. We are in the epoch of the nation-state. While this has not meant the end of war, internationally, there is more rational behaviour. Achieving a sustainable settlement of the region should be the only focus of all powers with a positive and beneficial attitude towards the region. War is no longer going to be fought in compartments. War is now an open battle. It affects everyone and everything. Governments also know this because a few governments are now beyond accountability. People extract a price if their affairs are not managed well. It affects all of us, and it is in the common interest of the rational world to find solutions to the conflicts in the region because I think Israel is also paying a very, very heavy price

Rami Niranjan Desai:

The international credibility of Israel is at an all-time low at this point. Do you think releasing the hostages held by Hamas would lead to a less assertive response from Israel, or do you think that will not change anything?

MJ Akbar:

You can’t clap with one hand. I mean, quid pro quo. That is the basis of all negotiations. There is no one-way offer. It won’t happen however much you may ask for it or however much you may wish for it. Both sides understand it. When we talk of the hostage crisis, why do you forget that a large number of hostages have been released? So, there have been deals before. Why should there not be a deal again? The problem, in my view, is the forces that have a vested interest in continuation of war. I’m not naming them because I don’t think guilt is only on one side.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

How can India play a role if the conflict remains localised and does not explode into something larger?

MJ Akbar:

The only nation that can become a bridge is one with pillars on both sides. India has pillars of goodwill on both sides, so why not India? However, this is a role that the US wants to play and has allotted to itself. But the Americans should also understand that this is an area in which India can help. The US could reach out to us. We do have a very good relationship with the White House, and here I mean a White House, irrespective of who’s the occupant of the White House.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

Correct. But as of now, what has been India’s position in the Israel-Hamas conflict?

MJ Akbar:

We have a position which is also the position of most nations, and that is to find a credible route map to a resolution. Do not treat conflict as an end in itself. What India is saying is in the interest of both sides. That is why it has credibility. India has no vested interest in the conflict but has a very strong vested interest in peace and in conflict resolution. But of course, it would require the acceptance of the US and perhaps Europe for India to find a place in the evolution of this unfortunate tragedy.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

Also in West Asia, one of the things that remains significant apart from what is happening right now is that we all talk about terrorism and it being a global security threat. Do you think India has some sort of leverage to combine its strength with West Asian countries to find some amount of cooperation to combat terrorism effectively?

MJ Akbar:

That fact is now non-negotiable. Terrorism as a weapon has been advertised as the weapon of the weak, and so on. Terrorism, however, is not acceptable, because the world has enough forums and enough space to move forward through the basis of negotiations. I once was asked by the Pakistani High Commissioner to Delhi as to when will there be peace talks. And I told him there will be peace talks when there is peace. You can’t have peace talks, at least in our bilateral situation, when you think that you can ignite terrorism as a form of blackmail. The Indian people are not ready to accept blackmail. So, abandon it. Why don’t you see the history of the last 50 years? There was a region called East Pakistan, which was as Pakistani as West Pakistan. Fifty years ago, it went through a cataclysmic liberation movement. After 50 years, it was not that relations with India instantly became better; they did not. There were dictators who continued to have a vested interest in conflict with India. But when Dhaka understood that it could gain far more from a positive relationship with India, look how well the relations have flourished. Look how Bangladesh has gained in terms of water, in terms of Farakka, in terms of all the neighbourhood requirements, the ten flights a day or more, perhaps now between India and Bangladesh. People are coming in, and people are benefiting. That is known as the reward of peace, which is the peace dividend. All we are asking is that every nation in the region recognise the enormity of the peace dividend and forget the very bloodstained returns of conflict.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

That’s so eloquently put. Even though we’re talking about West Asia, I’m always interested in Bangladesh. The kind of stability Bangladesh has had is because it had a stable government. It’s had Sheikh Hasina in the forefront. Pakistan doesn’t seem to have that. So is the expectation of peace too much to ask for?

MJ Akbar:

No, it’s not. While I have the greatest admiration for Sheikh Hasina, I have had the privilege of knowing her for a long while, when she was in a kind of isolation and in the opposition. What that Lady has gone through is a profile in courage and conviction and her own belief and ideals that is really, truly remarkable. The world should recognise that. What I’m also talking about is a national consciousness. And that national consciousness has existed in Bengal. So, Bangladesh has great projects with China. Well, it is an independent country. Why should it not? It is perfectly in its capacity and capability to exercise its will wherever it feels right. But today, the relationship between India and Bangladesh is crucial to the creation of economic growth advance in the whole region, our Northeast, Bengal and so on and so forth. All of it.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

Because we’re running out of time, I have a couple of questions that a lot of people here really want to know about. One is that we’ve been hearing a lot about the Petro deal. What do you think is happening there? How do you think it’s going to manifest? It’s likely that the Saudis will engage in the sale of crude oil in currencies other than the dollar. How do you see this playing out?

MJ Akbar:

It’s not just Saudis; it’s Russians. It’s the Chinese. It’s India. All countries are trying to find value in their currencies. The domination of one currency benefits only the owner of that currency. And this is taking a position not from a sense of hostility, but from seeking economic justice. If India and Iran, for example, can find value in each other’s currencies, well, why not? After all, currency is only an illusion. I mean, any rupee note is only as powerful as you believe it to be. A dollar is only as powerful as you believe it to be. When empires collapse, the first thing that collapses is the currency. So, every country would like to strengthen its currency. In a multipolar world, you will also need multipolar currency platforms.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

What if the US influence on the region were to decline? How would that impact the geopolitical landscape?

MJ Akbar:

I don’t think it would require an interest because again, influence is something that I have to also participate. If you’re going to influence me, I would also like to see some value in that inference. It’s all a question of negotiated value.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

How do you view the Chinese overtures in the region?

MJ Akbar:

China will play to its ability to try and expand its influence. It’s a kind of a quasi-China zone as far as it can, that is within its rights to do so. The interesting development, of course, is that after the break between China and Russia, after ’69, the return of the Moscow-Beijing partnership was a very, very vital element of the present-day world power equations. As we speak, President Putin has gone to North Korea and signed an agreement. North Korea is not an insignificant military power. The Chinese simultaneously have gone to South Korea, perhaps to allay fears that the Russian president’s visit to North Korea is not to be treated as hostile, but as part of equations that are important. As we speak, the Chinese are reaching out to Malaysia, and Putin has gone to Vietnam. So, old relationships are being revived, new relationships are being created, and new dimensions are being created to existing relationships. As the world is preparing for some degree of confrontation, I am not going to be so dramatic as to say it’s preparing for a World War. But it’d be more accurate to say that preparations are being made for a world confrontation.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

And the theatre of that would be?

MJ Akbar:

The theatre of that would be very, very visible. India, as the First Nation to declare independence from colonialism, has a profound historical significance. It has managed to retain the strengths of its unique ability not only to retain independence but to provide leadership to independent nations, which accumulates their influence without sacrifice of their independence.

Rami Niranjan Desai:

Thank you, Mr. Akbar. That gives us such a great overview of what is happening and what we can expect, even though, like you said, we don’t want to be too dramatic. But doesn’t look like a very bright sort of situation. But let me just end this short conversation with my last question to you. There’s been a lot of interest in IMEC, but it appears to be right now, in the back burner. How do you see the India Middle East Economic Corridor (IMEC).

MJ Akbar:

The IMEC is one of the ideas that has been on the table for a long while. Gwadar is another route, which is a parallel corridor. This is inception, early days. And these are ideas. These ideas first have to reach critical mass before they become a reality. Of course, that is the interesting part of international diplomacy. And you know, between the conception of an idea and the birth of an idea, there can be a long gap.

Brief Bios:

MJ Akbar: Shri MJ Akbar is the author of, among several titles, Tinderbox: The Past and Future of Pakistan. His latest book is Gandhi: A Life in Three Campaigns.

Rami Niranjan Desai: Rami Niranjan Desai is a Distinguished Fellow, India Foundation. An alumnus of King’s College, London she has degrees in Anthropology of Religion and Theology. She has been actively involved in research, fieldwork and analysis of conflict areas, with a special focus on the North East region of India for over a decade.

Transnational Jihad in West Asia and North Africa

كُتِبَ عَلَيْكُمُ الْقِتَالُ وَهُوَ كُرْهٌ لَكُمْ ۖ وَعَسَىٰ أَنْ تَكْرَهُوا شَيْئًا وَهُوَ خَيْرٌ لَكُمْ ۖ

وَعَسَىٰ أَنْ تُحِبُّوا شَيْئًا وَهُوَ شَرٌّ لَكُمْ ۗ وَاللَّهُ يَعْلَمُ وَأَنْتُمْ لَا تَعْلَمُونَ

Warfare has been prescribed for you, though it is repulsive to you. Yet it may be that you dislike something, which is good for you, and it may be that you love something, which is bad for you, and Allah knows and you do not know.

Surat Al Baqara : 216. سورة البقرة : ٢١٦

Introduction

Deaths from terrorism are now at their highest level since 2017- 8,352 in 2023, a 22 per cent increase from the previous year.[1] While ISIS, al-Qaida, and their affiliates have been very active, the major contribution to the death toll was from Hamas. The attack against southern Israel on October 7, 2023, by Hamas and ten other Palestinian armed groups, including the Islamic Jihad, Mujahideen Brigades, Al Nasser Salah al Deen Brigades, etc, has left thousands of dead, destroyed Gaza, and caused a human tragedy of colossal proportions. It has also acted like an adrenaline shot for reinvigorating transnational jihad.

Post October 7, 2023, the two main Jihadi configurations of the Islamic State (ISIS) and al-Qaeda have rejuvenated their subsidiaries, branches, and affiliates and are using the Palestinian cause and alleged human rights abuses in Gaza as the prime platform of their messaging, which aims at expanding their global threat potential. Similarly, the Hamas-Israel conflagration has given impetus to Iran’s Axis partners to invigorate their grid of militias in Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon, showcasing Tehran’s strategic influence both in its environs and globally. Christopher Wray, the Director of the FBI, while testifying to the Senate Intelligence Committee in December 2023, spoke of a ‘heightened threat environment’ after October. Earlier, in March 2024, General Michael Erik Kurilla, Commander of the United States Central Command (CENTCOM), observed that the capabilities of ISIS and al-Qaeda, and their affiliated groups, especially ISIS- Khorasan had escalated considerably.[2] The Israel-Hamas conflict, which is now in its 8th month, shows no signs of abating, despite horrific collateral damage and international opprobrium. The current global scenario will certainly throw up substantial challenges for counterterrorism agencies worldwide as jihadi groups will undoubtedly exploit the political fractures and hostilities that have become marked not only in the West Asia and African regions but also in the US, Russia, Europe, and South Asia, leading to proxy war scenarios, wherein counterterrorism initiatives suffer due to mistrust and political intransigence.

Unsurprisingly, 2024 started on a bloody note. On January 3, 2024, ISIS’s affiliate ISIS-Khorasan, attacked the commemorative ceremony marking the killing of the erstwhile IRGC head, Qasem Soleimani, in Kerman, Iran, which killed over 103 people. The same group was responsible for an attack on a Roman Catholic church in Istanbul, killing one person, and the March 22nd attack on the Crocus City Hall music venue in Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, Russia, killing over145. The attacks were all acknowledged by the ISIS mouthpiece Al Amaq News Agency, which also published laudatory messages from other ISIS branches and affiliates from West Asia and Africa. The reach and connections of the group with others in West Asia and Africa have raised blinking red lights, and an assessment of this threat perception is required not only for the security of the West Asia and North Africa (WANA), but globally.

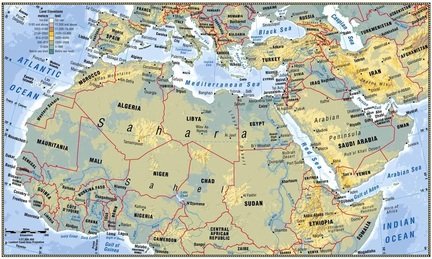

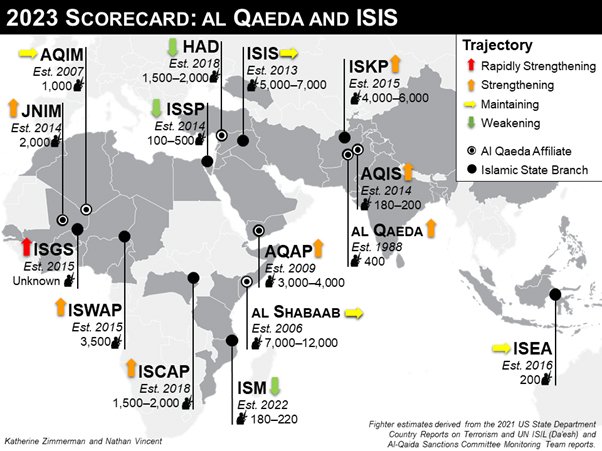

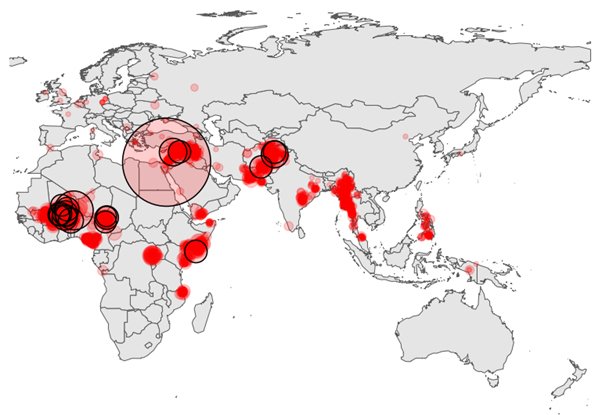

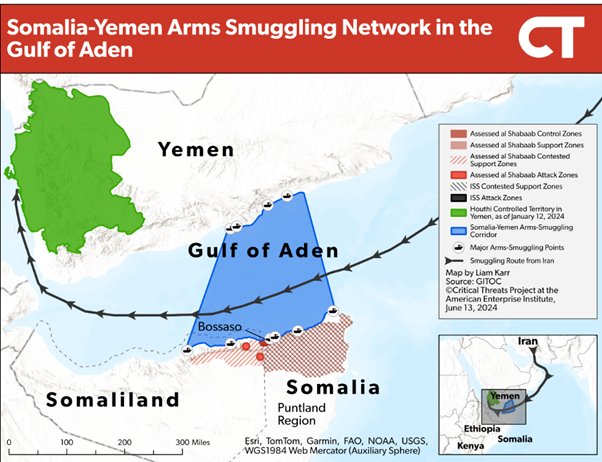

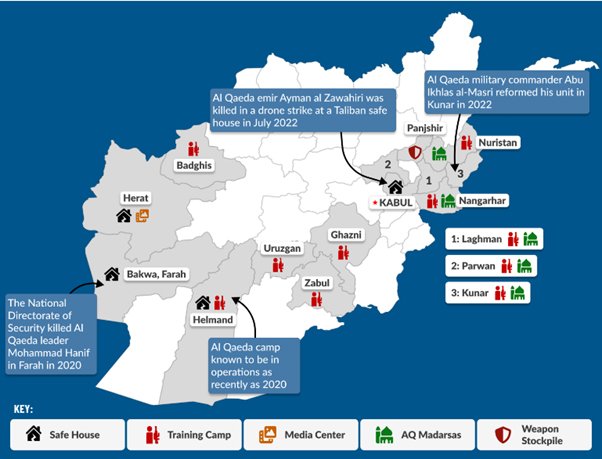

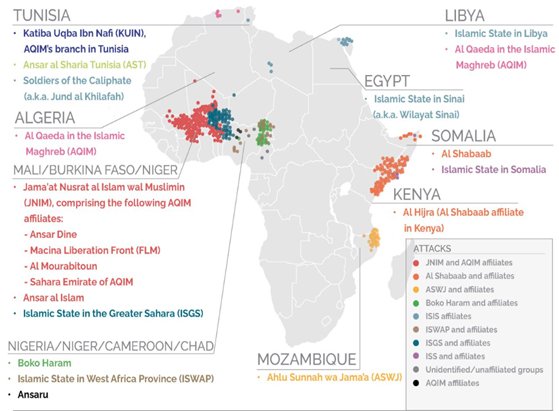

There are now several red flags about possible terrorist attacks, especially in WANA, and about cross continental linkages with south and southeast Asia and the Caucuses. The maps below show the areas, and linkages will be discussed below.[3]

As can be seen, the Salafi-jihadi threat has spread its tentacles around West Asia, Africa, and Asia. They have exploited local conflicts, co-opted local warlords and organised crime syndicates local conflicts and have used extortion and intimidation, apart from radicalisation. to strengthen popular insurgencies which are supportive. These groups have been wildly successful in Africa, where a series of coups have destabilised the region, and seriously hampered counterterrorism operations.[4]

The Taliban takeover in 2021 has provided sanctuary in Afghanistan for training recruits from Africa, West Asia, and South Asia and for arms collection from the withdrawing US forces. This was due to the respite from counterterrorism actions due to a severe breakdown of all government institutions and political and inter-communal conflagrations.

The Libyan situation continues to be grim, with a four-cornered internal insurgency raging, and the situation in Sudan has gone seriously downhill over the past few months due to the conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) escalating in Khartoum, destabilising government control and impacting fragile areas like Darfur, where mass killings and displacement have led to reports of ethnic cleansing.

In Syria, President Bashar Assad has managed to maintain the integrity of his country and the border; the Sykes Picot line remains intact. The central military conflict is now between the Syrian government and Turkish forces and factions within Syria. The conflicts continue to provide an optimum environment for Jihadi groups, which, although weakened, are by no means vanquished. The situation is similar in Iraq, and the Jihadi Salafi groups in the Levant have the potential to create local and global problems.

In 2023-2024, it has been seen that Jihadi Salafi groups, while focussing on the immediate areas of the Islamic world, have not lost sight of the more distant prospects, as evidenced by the Crocus Hall attack in Moscow, several attacks in Europe, and attempts in India and the USA. Post October 7th, there is a real and present danger from a terrorist act, as can be seen from the map of recent incidents given below.[5]

In this article, the transnational links of al-Qaida, ISIS, and other Salafi-Jihadi groups will be discussed, followed by a discussion on Iran’s “axis of resistance” and its burgeoning impact globally, and not just in the West Asian region.

The Global Reach of al-Qaeda: Networks and Allegiances

To revisit old history, Osama Bin Laden (Yemen/Saudi), Abdullah Azzam (Saudi), and Ayman Zawahiri (Egypt) and their cohorts, who had formed the Maktab al Khidmat, had been removed from Sudan at the encouragement of the US, as they had earned the ire of the Saudi Royal family, who did not want a Salafi contingent in a neighbouring country. The group was transported to Afghanistan by the US, and Nasrullah Babar, the then interior minister of Pakistan, introduced them to Mullah Omar, the Emir of the Taliban, to fight against the Soviet army. The Taliban, under the instructions of the Pakistani ISI, was told to extend them logistical and material help and fight under their guidance.

Post the Soviet defeat in 1988, the Maktab al Khidmat morphed into the al-Qaida, ostensibly for the spearheading of a global Islamic revolution that would eventually culminate in a Caliphate. The founders envisaged it as a “base” to which many other Jihadi outfits, like those from Uzbekistan and Xinjiang, and even the Rohingyas would join with the Ansars (foreign fighters). The al-Qaida was to stay as honoured guests of the Taliban and would acknowledge the Emir of the Taliban to be the Emir ul Momineen, the supreme leader of an Islamic community. The initial political motivations of settling the founders of al-Qaida, to use them against the Soviets, spectacularly backfired, leading to the bombing of the Kenyan embassy in August 1988, on the attack on USS Cole on October 12, 2000, in Aden, Yemen, and of course, the 9/11 attacks in the US.

Despite severe degradation following Operation Enduring Freedom, launched after 9/11, al-Qaida, after a short sabbatical, has emerged on the Global Jihadi map and has evolved into a decentralised network, with numerous affiliated groups across the globe pledging allegiance to its leadership.

Al-Qaida leadership

Al-Qaida faced a severe leadership crisis after the assassination of Osama bin Laden in 2011, followed by Anwar al Awlakki in Yemen in a drone strike (2011), and Nasir al Wuhyashi, who had been anointed as the next head of al-Qaida by Osama bin Laden, was also killed in Mukalla, Yemen, in 2015. The mantle of leadership did not fall on Ayman Zawahari, who was relegated to the position of group ideologue and notional Emir, with little control over day-to-day functioning or operational details. Operations and finances were being managed by Saif al Adel, based in Tehran, and Qassim al Raymi, the then head of the AQAP. They had envisaged and operationalised an attack against the US Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida in December 2019. The leadership council of the al-Qaida, including Zawahiri, was unaware of the operation, which caused considerable disarray in the Group’s central administration. Though he was nominally named the Emir of al-Qaida, his killing in a drone strike in the posh Wazir Akbar Khan area of Kabul in 2022 made little difference, and he has not been eulogised by the al-Qaida social media or print mouthpieces.[6]

Saif al Adel @ Mohammad Salah al Din Zaidan

Seif al Adel, an erstwhile special forces officer from Egypt who had been closely associated with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan and Pakistan, was earlier arrested when he, along with Osama bin Laden’s sons, Saad and Hamza, escaped to Iran. He was released through the efforts of Nasir al Wuhyasi, the then head of the AQAP, along with other cadres (see photo below), but refused to leave Teheran. Adel, who was reportedly close to the slain IRGC chief Qassem Soleimani, claimed that it would be better to have an al-Qaida presence in Iran, as there was a commonality of interest between the Iranian regime and the group regarding the “distant enemy,” the USA. His reluctance to leave Iran created dissent with the al-Qaida Central branch based in Afghanistan. Still, he bolstered his position by getting Tehran to have a line of communication with the al-Qaida, and by resonance with the Taliban. It needs to be noted, though, that the Iranian regime has refused to acknowledge the presence of Saif al Adel or other al-Qaida cadres in Iran. Also, it is significant to note that most attacks in Iran have been perpetrated by the ISIS, barring those by Baloch groups like Jaish e Adl in Sistan Baluchistan Province, and not by al-Qaida.

Saif Al Adel established control of the AQAP-al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula and co-opted its leaders. Saif al-Adel won the support of the Yemeni branch and used it to increase his direct influence in Syria. He created a new al-Qaeda group in Syria called Hurras al-Din (the Guardians of Religion) and established a channel for transferring funds and fighters from Yemen to Syria. This group worked along with the Jabhat ul Nusra, headed by Mohammed al Julani, the main AQ branch in Syria. These groups continue to be active in Syria under the tutelage of Adel. While counter-terrorism attacks by the US have degraded ISIS in the Levant considerably, the AQ fronts have been more insidious, won over allies from the Syrian armed opposition, and their cadres are actively involved with local governance in the large tracts of ungoverned areas in Syria, which also helps in getting funding through ill legal oil trades.

Situation with the AQAP

Meanwhile, in Yemen, Saad bin Atef al Awlakki, an acolyte of Saif Al Adel, was appointed as head in May this year following the assassination of the previous head, Khalid Batrafi. Awlakki is Yemeni and has made a public call to the provinces of Abyan and Shabwa in south Yemen to resist any overtures from the UAE government. With his ascension, reconciliation with the UAE and Saudi Arabia seems remote. Of great concern is that the AQAP has considerable heft in the provinces of Abyan, Shabwa, Marib, the port of Mukalla, Hadramawt and north Aden. AQAP has targeted armed groups backed by the UAE, such as the Southern Transitional Council, Security Belt, Shabwani Elite, and Shabwah Defense Forces, stating that Emirati mercenaries needed to be eliminated. Due to Saif Al Adel and the current AQ policy, they have no significant differences with the Houthis, who are acting as proxies of Iran, and since 2022, there have been no attacks by AQAP on the Houthis.

Saif Al Adel established control of the AQAP (al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula) and co-opted its leaders. Saif al-Adel won the support of the Yemeni branch and used it to increase his direct influence in Syria. He created a new al-Qaeda group in Syria called Hurras al-Din (the Guardians of Religion) and established a channel for transferring funds and fighters from Yemen to Syria. This group worked along with the Jabhat ul Nusra, headed by Mohammed al Julani, the main AQ branch in Syria. These groups continue to be active in Syria under the tutelage of Adel. While counter-terrorism attacks by the US have degraded ISIS in the Levant considerably, the AQ fronts have been more insidious, won over allies from the Syrian armed opposition, and their cadres are actively involved with local governance in the large tracts of ungoverned areas in Syria, which also helps in getting funding through ill legal oil trades.

Al Shabaab and its importance

The above development in Yemen needs to be assessed against the backdrop that the Al Shabaab, an affiliate of al-Qaida, has gained considerable ground in Somalia, even within the northern region of Puntland, and the port of Bossaso, which is on the other side of Aden across the Gulf of Aden, a main international shipping route. Harakat al Shabaab al Mujahideen, known as Al Shabaab (the youth), was formed by Aden Hashi Farah Aryo, a mujahideen trained in Afghanistan. It gained traction during Somalia’s civil war in the 1990s as an alliance of shari’a courts and local armed groups which gained power and territory during the 2006 Ethiopian invasion. It once controlled over 40% of the territory, including parts of Mogadishu. It is now headed by Ahmed Diriye, also known as Ahmed Umar Abu Ubaidah, who was involved in the West Mall attack in Kenya in 2013 and is a UN-designated terrorist.

Al Shabaab is showing remarkable resilience to counterterrorism initiatives by the African Union’s Transition Mission to Somalia (ATMIS) and Somali government forces and has often routed them with high levels of attrition. The ATMIS is winding down operations in Somalia, and it is apprehended that the resulting power vacuum will allow the Al Shabaab greater latitude. The group has now established some bases in Puntland, one area where international piracy initiatives were launched. The Al Shabaab leadership leaders have been covertly funding Somali pirates for revenue generation. Of global concern is the deal that the Houthis are forging with Al Shabaab for the supply of weapons. The two groups have an understanding, despite sectarian differences, that arms supply such as surface-to-air missiles and attack drones to the al Shabaab would seriously deteriorate the security scenario around the Gulf of Aden and Bab el Mandeb, the main shipping routes, especially for oil.[7]

Jama Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin-JNIM

The JNIM, which translates as the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims, is a prominent jihadist organisation in West Africa which was formed in March 2017. The JNIM is an amalgamation of several regional extremist groups, including Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Dine, the Macina Liberation Front, and Al-Mourabitoun. The Group’s formation was publicly announced by its leaders in a video message, signalling a unified front for Al-Qaeda. This was evidenced in the joint statement given out after the Hamas attack on Israel, which fulsomely praised Hamas and called for further attacks on Jews. The Group, which has expanded its reach across the Sahel region, including Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, aims to overthrow local governments and establish an Islamic state governed by Sharia law. It has engaged in kidnapping for ransom, attacks on military and civilian targets, and collaboration with other jihadist factions. The Group is closely affiliated with the AQAP and the Central AQ in Afghanistan.

The leader of JNIM is Iyad Ag Ghaly, a Malian Tuareg who previously led Ansar Dine. He was instrumental in removing French and other foreign troops from Mali. Under his command, the Group has pursued an agenda of implementing strict Sharia law for which he has formed various sub-units operating semi-autonomously across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. This decentralised approach allows JNIM to adapt to local conditions and maintain resilience, and it has shown considerable success against counter-terrorism efforts.

The Group has claimed responsibility for the attack on June 11, 2024, that killed over 100 Burkina Faso soldiers in Mansila area near the border with Niger. The site of the attack was close to the borders with Niger and Mali; both countries host insurgencies linked to both Al Qaeda and Islamic State. In another major attack on a gendarmerie and civilian auxiliary post in Burkina Faso on May 5, 2024, and a Nigerian army base on May 20 2024, over 100 people were killed. The brutality of the attacks has caused military forces to abandon the targeted bases, creating a power vacuum which the JNIM is filling. The political fallout has been a drift of the weakened governments towards Russia, causing consternation amongst the US and allies about potential strategic losses over political heft and valuable natural resources.

Call for Jihad

Saif Al Adel, the Emir of the Al Qaida, called (June 2024) upon “the loyal people of the Ummah interested in change to go to Afghanistan, learn from its conditions, and benefit from the Taliban’s experience. This call was issued by the as-Sahab media, a mouthpiece of the organisation, titled “This is Gaza: A War of Existence, Not a War of Borders.”[8]

The call makes it clear that al Qaida has established bases in Afghanistan, and believe that they have political immunity there. His call for’ Hijra’ is reminiscent of the early 1990s. He further adds that all Islamic people should strike to cause maximum pain against ‘Zionist” targets around the world.[9]

Simultaneously, the AQAP has launched a new online anti-West propaganda campaign called “Inspire Tweets” which exhorts the Ummah that jihad is the only solution, the need of the hour is for supporters to engage in various types of attacks including bombings, armed assaults on unexpected targets, and strikes on train stations and airports to retaliate for killing Muslims. Additionally, the campaign calls on al-Qaeda supporters to carry out cyberattacks to hurt western economies. Earlier in December 2023, tweets asked followers to use ‘Open-Source Jihad (OSJ)’ material titled ‘The Hidden Bomb,’ directed at lone wolves, and groups of supporters, which had guidelines and tips on how to make IEDs, bypass standard security measures in United States airports etc.[10]

This call for Hijra and the open-source jihad needs to be seen in tandem with a United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team report dated January 29th that states that the al-Qaida has opened eight new training camps, five madrasas, a weapons depot and safe houses in Afghanistan, that are used to facilitate the movement of its members to and from Iran and other areas in West Asia and Africa. The report further reiterates the close connection between the Taliban and al-Qaida.[11]

Afghanistan and Transnational Jihad

With al-Qaida opening doors for foreign jihadis, the pathway has also been facilitated for ISIS cadres, especially as ISKP has become one of the most active vilayats of ISIS. This, combined with the anti-migration policies of the EU and USA, will likely cause a reverse flow into Afghanistan. Several Jihadis from various countries are now seen in Afghanistan, an eerie recall of the early 1990s.

Over the last few decades, several jihadist organisations have tried to get a global outreach, be it the AQ, AQAP, Al Shabaab, or the various factions of ISIS. ISKP has been spectacularly successful, as witnessed in the latest attacks in Iran, Turkiye, and Moscow. But unlike other groups, the ISKP has no stable space in Afghanistan and is in constant battle with the Taliban and AQ, both for control of territory and drug trading routes. Since 2022, the Taliban, with some international help, has been systematically degrading the ISKP. On its part, ISIS, in the August 28, 2022, issue of its Pushto magazine Khorasan Ghag, claimed that its reduced activity was because the group’s Emir -Shahad al Muhajir had decided on a “strategic silence” policy. The policy was soon revised, and the group set up the Azaim Media Foundation, which publishes in Arabic, English, Pushto Urdu, Russian, Swahili, etc. The online messages and tweets are getting responses from all over West Asia and Africa for recruitment, funding, and logistic support.

Hence, it is seen that despite claims by the Taliban that no foreign terrorist group would be able to function on Afghan soil, the quality and number of attacks have escalated since 2022 end. The ISKP, from its tenuous holdings in Afghanistan, has set up recruitment and financial networks in West Asia, Europe, Somalia, and the US and has emerged as an integral part of the transnational jihad and one of the main contributors to ISIS’s terrorist profile.

ISIS in Syria and Iraq

On March 23, 2019, the coalition forces, led by the USA, claimed that they had liberated the final stretch of territory controlled by ISIS in Baghuz, Syria. But though ISIS has lost Mosul (Iraq) and Raqqa (Syria) and has been degraded in Syria and Iraq, the group is far from moribund, has a network of agents and sleeper cells in those countries, and has systematically set up branches all over the globe. In the Levant, counterterrorism pressure has degraded the Islamic State’s global senior leadership, including those leading efforts to conduct attacks in Europe. However, despite significant losses among senior ranks, the group has adapted by decentralising its command structures. The name of the current Caliph -the fifth one- Abu Hafs Al-Hashimi Al-Quraishi, was announced in August 2023 by his spokesman Al-Ansari. He has, however, ostensibly for security reasons, remained undercover, and his real identity is unknown, which has led members to question his credentials. In November 2023, the pro-ISIS Bariqah News Agency hinted that an audio or video message by the Caliph might not be ready for quite some time, indicating that he will remain undercover. Some reports have suggested that he has travelled from Yemen to Somalia.

This appears to be a real possibility, as for the present the ISS- Islamic State in Somalia, is the most active branch, which has strong links with ISKP. Following the January 4, 2024, audio message by ISIS Spokesman Abu Ḥudhayfah Al-Ansari, in which he pledged to escalate attacks across all regions in support of the “Muslims” in Gaza., there has been a quantifiable increase in violence and threat perceptions in the region has escalated. Currently there are an estimated 2500 Islamic State fighters in Syria and Iraq— more than double estimates from late January.

There have been around 69 confirmed attacks by the Islamic State in central Syria till June 2024.The attacks in Badia, in March this year resulted in the deaths of at least 84 Syrian soldiers and 44 civilians. This was followed by attacks in the desert area of Homs, with over 15 soldiers of the Syrian armed forces loyal to President Bashar Assad killed. The scale of violence against the security forces was alarming as ISIS cadres stormed regime outposts, ambushed patrols, capturing and executing soldiers and capturing arms. There were also targeted attacks on the US backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Armed forces abandoned posts, leaving large swathes of the country without security cover. The UN assessed in January this year that the IS had established an operational hub in the Badia desert in Central Syria, but opined that it was likely that Syrian Government and Russian forces would neutralise/ contain it soon.[12]

The situation is similar in Iraq. Of note is the attack on May 13, 2024, this year on military outposts in eastern Diyala and Salahuddin provinces, where a commanding officer and several soldiers were killed. These attacks in Syria and Iraq suggest that the rural areas continue to harbour militant cells, and that the earlier declaration of victory over ISIS in Iraq and Syria by the U.S was a little premature. Problems, including sectarian divisions and proxy wars, have undeniably undermined the Iraqi government’s counter terrorism efforts and enabled the ISIS’s revival. The Iraqi government has also been hamstrung by the U.S. partial withdrawal of forces in 2021, but the armed forces are rallying around, and have conducted several counter-terrorist operations. In March 2024 , the Iraqi forces launched a notable offensive, that resulted in the death of a prominent ISIS leader, Samir Khader Sharif Shihan al-Nimrawi who was the point person for transfer of funds arms and cadres between Syria and Iraq.

Moreover, Prime Minister Mohammad Al-Sudani’s government has had to battle crippling sectarian polarisation that occurred after the US intervention in Iraq in2003. This problem is still some way before resolution, and added to the current geopolitical turmoil in the region stemming from the ongoing Israel–Hamas war has undermined regional stability and encouraged ISIS’s resurgence in the region.

ISIS in North Africa

Over the last few years, successful counterterrorism operations and the rigid enforcement of strict national anti-terrorism legislation, coupled with innovative deradicalisation and rehabilitation programmes, have diminished the threat posed by ISIS in Egypt. The Egyptian government has invested in several development and infrastructure policies in the area where the local branch of the Islamic State, also known as vilayat Sinai or Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (ABM) is active. However there still are some active cadres who periodically attempt to attack the Security forces, especially around the Sinai. The last violent clash between the Egyptian army and ABM was in 2022 near the Suez Canal. Still, the terrorists were soon overpowered, a tribute to the excellence of the Egyptian intelligence service, the GIS (General Intelligence Service). It needs to be pointed out that the GIS, which has excellent HUMINT, had informed Mossad about the possibility of a major Hamas attack across the Gaza Strip in September this year.

In Libya, jihadist groups are facing several challenges due to sustained counterterrorism attacks against their positions. In southern areas like Fezzan, clashes between the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda are helping security forces. On its part the ISIS, exploiting the political and economic predicament in southern Libya is cooperating with tribal elements involved in smuggling, human trafficking and illicit trade, which helps the group to be financially stable and helps recruitment. According to a recent report by Europol, Syrian mercenaries – often with radicalised profiles are being brought into Libya– by Russia (through the Wagner Group), who might pose additional security risks to the country.

Morocco has not had an Islamist-inspired attack since 2018 but remains vigilant over the offline and online threat of violent extremism. The Moroccan intelligence has prevented several attacks and dismantled jihadist cells that operate in cyberspace. The Moroccon deradicalisation and reintegration programmes, such as ‘Moussalaha’ (‘Reconciliation’), have proved to be very successful and can serve as a blue print for other countries. It has benefited hundreds of jihadists, especially foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) returnees. The situation in Algeria is much the same, and due to tight security mechanisms and reconciliation policies that allow jihadists who surrender to security services, which would give them information, to receive amnesty and economic assistance.

Tunisia continues to face several terrorist-related challenges. Jihadist groups such as Katibat Uqba Bin Nafi (KUIN) and Jund Al-Khilafa (JAK), which, though weakened – are active in the mountainous areas along the Tunisian-Algerian border. They pose the risk of guerrilla /lone wolf attacks. Also, Tunisian rehabilitation programmes are not as well received or as exhaustive as the Moroccan programmes, and hence, Algiers continues to face problems with the foreign returned fighters.[13]

Map of Jihadist groups in Africa

Jihadi groups in Africa

Violent conflict is one of the main factors driving terrorism, with over 90 per cent of attacks and 98 per cent of terrorism deaths in 2023 taking place in countries in conflict; all the African countries impacted by terrorism have been involved in prolonged armed struggles. In the current global scenario, the epicentre of terrorism has shifted from West Asia and North Africa into sub-Saharan Africa, mainly in the Sahel. Around 59 per cent of all fatalities due to terrorist attacks are from the Sahel, with significant contributions from Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, Niger, and Somalia in the east. These conflicts are important as they often morph into proxy wars with powerful countries, which signal a lack of ethics. These proxies usually result in debilitated governance, mass migration, hunger, and uncontrolled climate change, leading to coups with uncertain futures. Apart from endangering relations with neighbouring countries, many nations with coups have withdrawn from international bodies such as ECOWAS and local peacekeeping forces.

The nexus between organised crime and terrorist groups in the Sahel is marked by illegal gold mining and oil trading, apart from human and drug trafficking, kidnapping and extortion, and livestock hustling and activities such as cattle and livestock rustling.[15] Notable examples of such groups are the JNIM, the Boko Haram in Nigeria, etc, which are affiliated with al-Qaida and the Islamic State vilayats in Africa. These are usually active in the same areas, frequently leading to violent clashes between the groups. While these clashes have a debilitating effect on the social fabric, resulting in mass migration and human rights abuses, they help counterterrorism initiatives by local governments and international agencies. Criminal activities ensure that these groups in the Sahel are reasonably well funded and able to support the central leadership, including proactive branches like the ISKP.

ISIS DRC

According to U.S. Intelligence, the senior ISIS leadership is of the view that Africa is an area where they should invest time and energy, as the continuing conflicts there make for a permissive environment. The I.S. announced the launch of the Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP) in April 2019 as a unified structure between ISIS-Democratic DRC and ISIS-Mozambique. The Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan Muslim insurgent faction active in eastern Congo since the 1990s, had committed a wave of brutal attacks on civilians in late 2019 and killed around 850 people last year, according to U.N. figures. The ADF, which gained prominence for attacking Christian communities, has morphed into the ISCAP, which is now trying to expand its sphere of influence. The group is said to be involved in diamond and gold smuggling and has efficient financial and recruitment networks.[16]

Ugandan and DRC armed forces have been launching attacks on ISCAP positions, but the group has shown considerable resilience. On January 24th this year, ISCAP launched a major attack in Ngite, in the territory of Beni, in resource-rich North Kivu province, which borders Rwanda, causing security forces to withdraw from the area. ISCAP has entrenched itself in the region, which is on the route of transporting Cobalt and diamonds. In December, the group was accused of two attacks in western Uganda in which 13 villagers were killed. The DRC, which continues to have a low-intensity conflagration with Rwanda, is conducive to I.S. growth due to its internal turmoil. The ISCAP could cause severe problems in the future and impact WANA.

Islamic State in Somalia (ISS)