Introduction

The May 6, 2025, India-Pakistan conflict has raised questions about the future of South Asia’s regional economic integration. India has ceased all direct and indirect trade with Pakistan, halting a $10 billion annual exchange of goods. South Asia, as a region of aspiration, seems lost for some time. However, the geographical reality of proximity, common borders, and cultural affinity cannot be changed. India is a key destination for the shift of supply chains from China, and the region is the catchment area for these benefits. How, then, can the region play its role as the next big trade hub?

There are currently three imperatives for India to emerge as a manufacturing hub. The first is the Trump tariff effect, where India faces 26% reciprocal tariffs on exports to the US, the world’s largest high-income market. A second factor is Pakistan, whose tepid growth, low productivity, and lack of domestic reform are hindering the region, depriving it of the benefits of developing a supply chain ecosystem and ultimately prosperity. Thirdly, China and East Asia’s integration into global supply chains, which has generated jobs and unprecedented prosperity, provides valuable lessons for others, even amidst global trade policy uncertainty.

This indicates that South Asia is increasingly leaning towards trade in the new geopolitical context. Indeed, India is enhancing its trade engagement with the world, showcasing a series of free trade agreements (FTAs). Recently, Sri Lanka signed FTAS with Thailand and Singapore. Meanwhile, Bangladesh has been discussing FTAs with various Asian countries. This reflects a regional aspiration to establish the supply chain ecosystem necessary for an ambitious trade agenda.

It is none too soon. Starting in June, all of Apple’s iPhones for the U.S. market will be made in India, still cheaper despite the new U.S. tariffs. Samsung, Volvo, Siemens, and Amazon have announced they will expand their manufacturing footprint in the country. This is not a sudden shift following the imposition of U.S. tariffs. Multinational companies had already begun reducing their dependence on China before Covid-19, and its popularity as a manufacturing source was receding, particularly among Western firms.

This essay, therefore, examines the prospects for India and the rest of South Asia. It seeks to address the following questions:

- Is India rising as a global manufacturing hub?

- Is trade diplomacy in high gear at last?

- What lessons can we learn from China?

- How can India’s neighbours be lifted?

India’s Role in Global Manufacturing

The disruption of China-centric global supply chains is underway, with reports indicating that inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has fallen to historic lows for both the U.S. and China (Baldwin, Freeman & Theodorakopoulos, 2023). The migration of labour-intensive supply chains from China to lower-cost locations can be attributed to rising wages, domestic supply chain bottlenecks, and investor concerns about stricter regulation of foreign companies, along with the escalating trade war between Washington and Beijing. Vietnam and Thailand have emerged as significant beneficiaries of these supply chain shifts. India is now being positioned to become a complementary Asian manufacturing hub to China (Wignaraja, 2023), regarded as a reliable alternative destination among the largest global FDI recipients, driven by its rapid economic growth, a large educated labour pool, and a vast domestic market (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2023).

An influential view, most prominently presented by Rajan and Lamba (2024), argues that India’s services sector is the primary driver of economic growth in an increasingly globalised world of services. They suggest that India should leverage its comparative advantages in labour to enhance its role in both the domestic economy and global services trade, particularly in digitally delivered services. They conclude that India ought to invest more in human capital and skills to capitalise on this strength in services. This view holds some merit, as India does possess favourable demographics with a youthful population, providing ample supplies of low-cost manpower. However, international development history indicates that relying solely on services development may be inadequate for a large economy like India to progress beyond lower middle status and create high-quality jobs.

The crucial role of manufacturing development in generating jobs and prosperity is emphasised by the East Asian miracle story. This narrative begins with the industrialisation of Japan during the inter-war period, followed by the emergence of the four East Asian dragon economies (Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore) in the 1960s and 1970s, and China since the 2000s. Looking further back in history, the rise of the UK, Germany, and the US occurred alongside the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Furthermore, the evidence suggests that pessimism regarding manufacturing and supply chains in India appears to be shifting at last. One indication comes from within the Indian manufacturing sector itself. The Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) summarises whether market conditions for manufacturing are expanding, remaining the same, or contracting, as perceived by purchasing managers. India’s PMI is well above 50, relatively high compared to comparator economies including China and Indonesia (ADB, 2025). Furthermore, there have been significant micro-level investments by global MNCs in India. Prominent among these is Apple, which has been ramping up its manufacturing of iPhones in India since 2020; Toyota has increased its investment by establishing a new plant in Karnataka, and Hyundai’s 2024 investment in Maharashtra has enhanced its capacity and encouraged technological advancement. India’s manufacturing sectors in areas such as automotives, pharmaceuticals, and electronics assembly are already well-established and stand to benefit from a series of policy initiatives, which have resulted in a 69% increase in FDI equity inflow in the manufacturing sector over the past decade of 2014-24 compared to the previous decade of 2004-14.

Perhaps most important in uncertain global times has been the visible advancement in India’s defence manufacturing sector, largely due to the Make in India initiative (Ahuja, 2024). In 2023-24, it experienced an increase of 174% (CK) over the past decade, along with a boost in exports. India aims to become a defence manufacturing hub, targeting ₹3 lakh crore ($35 billion CK) in defence production by 2029. Start-ups, large domestic companies, and multinationals are actively developing a range of products. For instance, in 2024, Airbus, in partnership with Tata Advanced Systems, inaugurated a C295 final assembly line complex in Gujarat for producing military transport aircraft for the domestic market.

An impressive performance has been that of the BrahMos, a long-range supersonic cruise missile developed collaboratively by India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and Russia’s NPO Mashinostroyeniya. India exported the BrahMos to the Philippines in 2024, and in 2025, it has been in talks with Vietnam and Indonesia for similar exports. In the conflict between India and Pakistan on 7-8 May 2025, the vastly superior performance of the BrahMos has resulted in increased inquiries for exports and enhanced discussions between India and Russia for advanced versions of the missile.

With this new confidence, India needs reforms that promote trade openness, reduce the red tape regulations strangling businesses, and facilitate investments in renewable green energy (Das, 2024; World Bank, 2024). Closer policy coordination between the central government and India’s semi-autonomous states is essential in areas such as attracting foreign direct investment and cross-provincial infrastructure development (including national highways and high-speed road networks).

Is there some merit in revisiting India’s landmark 1991 reforms? Influential commentators like Douglas Irwin (2025) suggest that the political economy of reforms matters. He argues that in 1991, reform-minded technocrats persuaded political leaders to reject what had been a standard response to balance of payments pressure (import repression to avoid a devaluation) and embrace a new approach (exchange rate adjustment and a reduction of import restrictions). Several other elements now need to coalesce. Supply chains rely on a multitude of service inputs. In this vein, India’s service sectors (including information and communications technology, financial and professional services, and transport and logistics) are also positioned for growth.

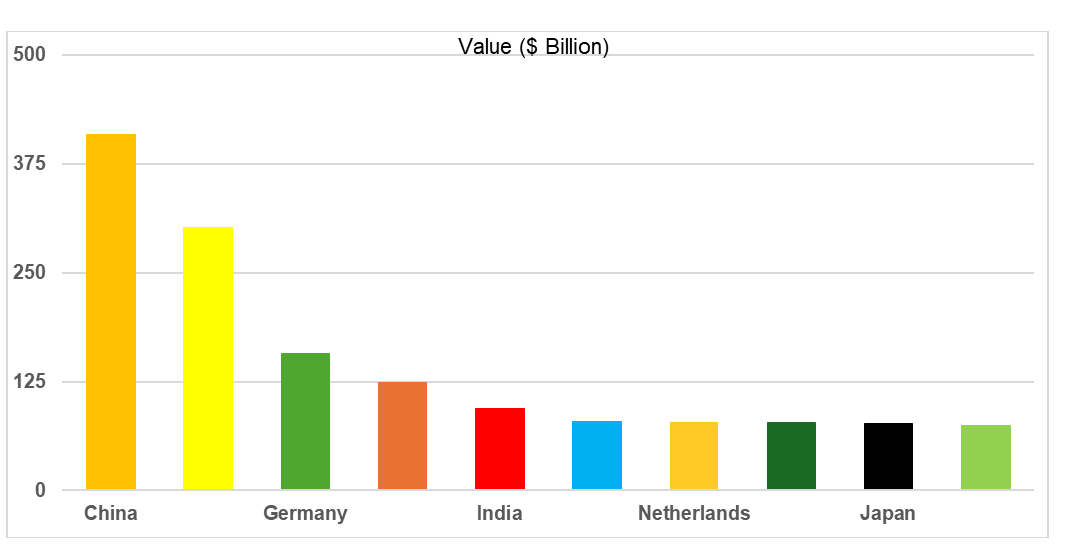

The final goods produced in these factories rely on sophisticated semi-finished goods from abroad, which have contributed to the growing Indian imports of intermediate goods. Thus, a second indication of India’s ascent in the global supply chain is its role as a major global importer of intermediate goods. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the WTO ranked India as the fifth-largest importer of intermediate goods (see Figure 1) – up from the 10th rank in the second quarter of 2021. In 2023, India was behind top global importers such as China, the U.S., Germany, and Hong Kong. The country is now positioned ahead of European developed country importers (the UK, Netherlands, and France) as well as Japan. Few foresaw India’s emergence as a leading global importer of intermediates a decade ago.

Figure 1: World’s Ten Largest Intermediate Goods Importers

Notes: Figures in $billion

Source: World Trade Organisation, 2023

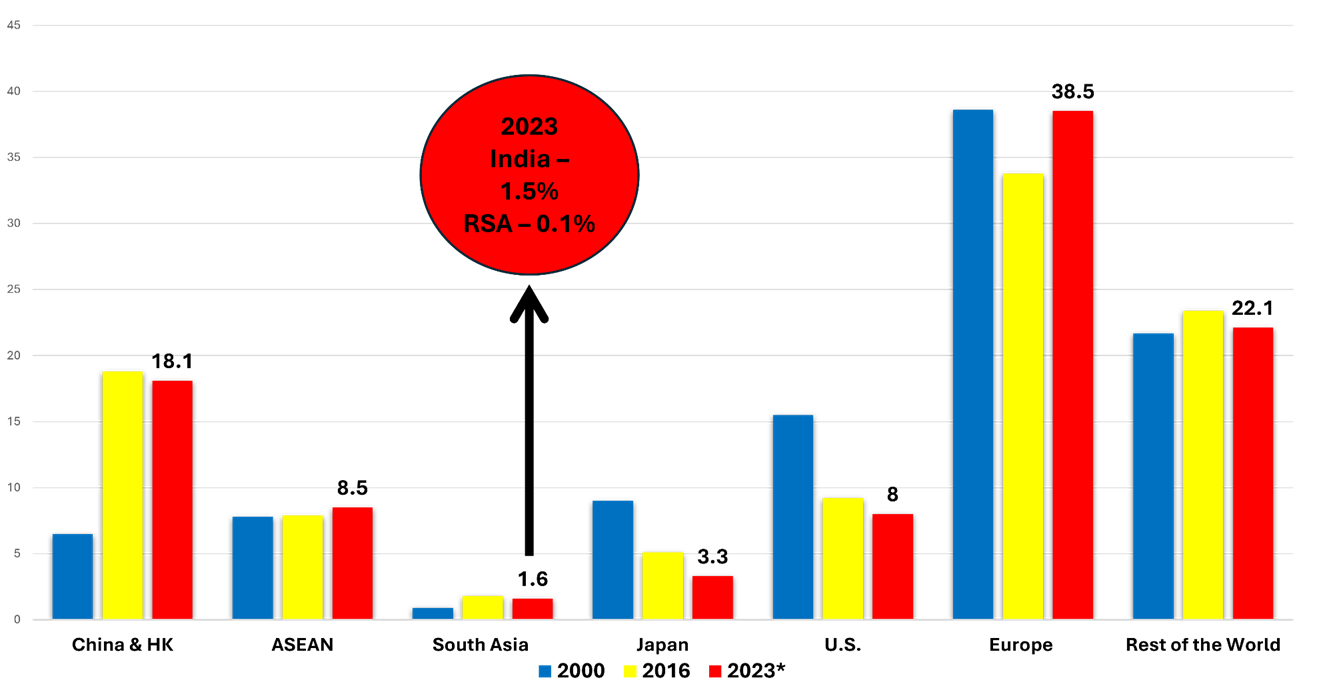

A third indication of India’s role in global supply chains is its position as an exporter of intermediate goods. Here, the data suggest that India and South Asia as a whole are relatively small players in supply chains compared to East Asian or developed economies. Between 2000 and 2023, India’s share of world intermediate goods exports doubled from a modest 0.8% to 1.5% (see Figure 2). Adding the rest of South Asia (an estimated 0.1% of world intermediate goods exports) to India’s share yields a tiny regional total of only 1.6% in 2023. Meanwhile, China and Hong Kong account for 18.1% of the world share, and ASEAN contributes another 8.5%. Although declining, Japan, the U.S., and the EU hold larger world shares than South Asia.

Furthermore, there are very limited regional spillovers from India’s supply chain activities to the rest of South Asia. Intra-regional trade in South Asia, at 5% in 2017, is among the lowest globally. This positions South Asia as one of the world’s most economically disconnected regions. Despite its increasing trade volume with the world, India’s trade with its neighbours constitutes between 1.7% and 3.8% of its global trade. India’s largest regional trading partner is Bangladesh, followed by Sri Lanka and Nepal.

Figure 2: South Asia in World Shares of Intermediate Goods Export (%)

Note: * represents estimates

Source: WTO (2023), Wignaraja (2023)

Trade Diplomacy in High Gear

Since 2022, the Modi government has renewed its emphasis on preferential openings with trading partners through a series of bilateral trade deals, such as the UAE-India Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement and the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA). Additionally, it has joined significant regional trade frameworks like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) (Dhar 2022). A trade agreement signed with the UK in May 2025 offers notable gains in services and ambitious market access (Wignaraja, 2025). This will enhance ongoing negotiations with the EU to conclude an equally comprehensive, high-standard FTA and with the U.S. for a partial Bilateral Trade Agreement. India is a latecomer to Asia’s FTA bandwagon but is striving to catch up with East Asia (Kawai and Wignaraja, 2013; Wignaraja, 2022). According to the Asian Development Bank’s Asia Regional Integration Centre database, India has 17 concluded FTAs and another 19 under negotiation (see Table 1). In terms of concluded FTAs, India ranks alongside leading Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia (19), Malaysia (19), Thailand (16), and Viet Nam (18).

The geopolitical signalling regarding trade openness in 2025 is significant. India is progressing with free trade agreements with the Global North, which has positive implications across the board. Firstly, an India-EU FTA alongside an India-UK FTA could strengthen reformed global rule-making on international trade and potentially revitalise the WTO – a stated goal of India. Secondly, FTAs act as a stepping stone to India’s membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP, a high-standard mega FTA that reduces trade barriers for its members and which India declined to join, represents a significant share of world trade. The 12 members, including Japan and the UK, collectively account for 15% of global trade and 15% of world GDP.

The CPTPP includes agendas for services, trade, investment rules, intellectual property rights, government procurement, etc., which support the spread of supply chains. Consultations with businesses during FTA negotiations and the provision of business development services for FTA implementation are essential, as trade and investment do not necessarily increase merely because an FTA is signed.

As Indian businesses gain experience and confidence in trading under the agreements with the Global North, facilitating closer economic integration, India can effectively study the economic benefits and costs of CPTPP accession. It provides access to multiple markets at once, will benefit India from the China+1 strategy, and boost business for MSMEs, which account for 40% of India’s exports. This will resonate throughout South Asia, where SMEs are the backbone of these economies but do not yet contribute significantly to exports.

Table 1: South Asia: Joining the bandwagon of FTAs

| Country | Negotiations launched | Concluded FTAs |

| Japan | 7 | 21 |

| China, People’s Republic of | 8 | 25 |

| Korea, Republic of | 12 | 28 |

| Hong Kong, China | 1 | 9 |

| Taipei,China | 2 | 6 |

| Brunei | 1 | 11 |

| Cambodia | 1 | 11 |

| Indonesia | 11 | 19 |

| Malaysia | 8 | 19 |

| Philippines | 3 | 11 |

| Singapore | 7 | 35 |

| Thailand | 10 | 16 |

| Vietnam | 2 | 18 |

| India | 19 | 17 |

| Sri Lanka | 5 | 7 |

| Bangladesh | 3 | 5 |

| Pakistan | 6 | 13 |

| Maldives | 1 | 4 |

| Bhutan | 2 | 3 |

Source: Asia Regional Integration Center, February 2025

At home, the FTAs will provide the country with a unique opportunity to implement necessary reforms and open up its economy, as it did in 1991. This, in turn, will increase foreign capital, enhance skills, foster R&D and innovation, and drive the country towards a more competitive and open economy.

Thus far, India has undertaken the following initiatives to enhance manufacturing:

- Make in India: Launched in September 2014, it aimed to transform India into a global design and manufacturing hub. The focus was on facilitating business by reforming policies to make them more investor-friendly and emphasising infrastructure development.

- Atmanirbhar Bharat: Launched in May 2020, the Self-Reliant India Campaign focused on reforming seven key sectors, particularly to facilitate business.

- Product Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme: Launched as a continuation of Atmanirbhar Bharat, this initiative provides financial incentives for increased production and incremental sales across an additional 14 sectors. The objective is to support and enhance India’s manufacturing sector.

Lessons from China

Some aspects of China’s industrial policy may be relevant to India, such as better targeting of multinationals with which to partner for new industrial endeavours that could provide potential comparative advantages. It necessitates improved coordination between the central government and state administrations. Equally important is investment in higher education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

However, industrial policy is a contentious area, and caution should be exercised before India attempts to emulate China’s state interventionist template. Significant risks include government failure and cronyism. It would be prudent to engage actively with think tanks to gain insights into what might work. Still, India can learn much from China’s experience.

- Lesson 1: Promoting export-oriented FDI. Trade liberalisation entails an open-door policy towards FDI in manufacturing and encourages high-level investment, offering competitive incentives and establishing modern SEZs as public-private partnerships.

- Lesson 2: Reducing business hurdles. The digitalisation of taxes, customs fees, and business administration is essential. Industrial policy aimed at facilitating the green transition and trade is increasingly being employed and can yield significant benefits.

- Lesson 3: Fostering regional supply chains. India should promote regional supply chains by scaling up the Make in India programme to a Make in South Asia initiative. India can offer fiscal incentives to its manufacturers to expand into Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The food processing, textiles, apparel, and automotive sectors are suitable for regional expansion, considering the factories and expertise of these neighbours.

Lifting Up India’s Neighbours

At present, much of South Asia is not a significant part of India’s trade narrative, despite the economic potential of certain countries. Therefore, it is economically beneficial for India to disseminate the advantages from this trade regionally, fostering resilient and cost-effective regional supply chains in South Asia. This will stabilise the region, create jobs, and render its neighbours less vulnerable to the potential risks associated with Chinese infrastructure investments, including debt distress linked to high interest, low return port projects, as well as environmental challenges (e.g. deforestation, habitat destruction, water pollution, and increased carbon emissions).

In this spirit, India-Sri Lanka FTA talks could be resumed, with a view to concluding an investment deal, followed by a more comprehensive FTA. Cutting redundant business regulations and strengthening investor protections in Sri Lanka are crucial for attracting Indian foreign investors to the country’s ports, logistics, renewable energy, digital economy, and tourism ventures. Such ventures generate much-needed foreign exchange and provide Sri Lanka with a path away from indebtedness and towards transformative growth.

A sure way for South Asia to establish resilient and cost-effective regional supply chains is for Indian businesses to invest in the region and cultivate substantial local linkages and spillovers for their South Asian partners (Kathuria, Yatawara and Zhu, 2021). This is already occurring to a limited extent in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. The Adani Group, for instance, has invested in a joint venture with John Keels Holdings to develop the West Container Terminal at Colombo Port. This project leverages Sri Lanka’s advantageous geographical position along the main East-West global sea route and transhipment trade to India.

Bangladesh was growing rapidly, boasting a larger domestic market and cheaper wages than Sri Lanka, until its internal crisis. It had become an attractive destination for Indian FDI in the manufacturing sector. Tata Motors, Hero MotoCorp, Sun Pharma, Godrej, VIP, CEAT Tyres, and Aditya Birla Cement all established factories in Bangladesh. A natural corollary would have been increased private investment in consumer-oriented sectors and start-ups focused on fintech, healthcare, and agritech, aimed at developing a local ecosystem with access to seed funding and technology transfer from India. However, these potential developments are now on hold due to political events.

India-Sri Lanka: A Model for South Asian Cooperation

The joint statement released following Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Colombo in April 2025, and Sri Lanka’s President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s visit to New Delhi in December 2024, highlighted India’s commitment to assist Sri Lanka in becoming an energy hub, strengthening India-Sri Lanka defence cooperation, enhancing educational, health, and technological exchanges, and promoting Indian FDI in Sri Lanka.

It is evident that India recognises Sri Lanka as a premier partner in transforming South Asia into a progressive economic region amid an uncertain global economy. Sri Lanka has recorded the highest GDP per capita in South Asia, peaking at $4,388 in 2017, driven by a robust machine of medium and small enterprises. Its decline over five years to $3,3431 per capita has dealt a blow to a country used to a comfortable standard of living. This is what Dissanayake has pledged to reverse. He has affirmed that Sri Lanka will proceed with its 17th IMF programme while increasing social spending to alleviate high poverty levels. He is enhancing governance by implementing anti-corruption measures, digitising the government, and modernising agriculture.

The bilateral agreements with India assist the new government in continuing these efforts and shifting the focus of the relationship from aid to trade. India has committed to supporting Sri Lanka in the digitalisation of its public services, a model that India has pioneered, which will aid in fulfilling some of the promises made by the NPP for targeted social protection and anti-corruption. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed during PM Modi’s visit to Colombo in April 2025 with Sri Lanka to establish a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) connection for importing and exporting power. A tri-partite agreement between India, the UAE, and Sri Lanka to develop Trincomalee into an energy hub is a model that can be replicated in other sectors.

It’s a promising start that can elevate the bilateral relationship to resemble the close cooperation evident among Thailand, Cambodia, and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, for instance, in the Greater Mekong sub-region. New Delhi and Colombo can consider piloting a regional PLI scheme in Sri Lanka, similar to the Government of India’s efforts to build domestic capabilities in sophisticated manufacturing industries, including solar panels, electric vehicles, and electronic components. A limited extension of the domestic PLI scheme to Indian businesses for manufacturing solar panels in Sri Lanka will mitigate the risks of overseas investment and foster regional supply chains in the neighbourhood – a key goal for India’s China+1 strategy.

Such enhanced cooperation with Sri Lanka is almost a necessity. India is facing a hostile neighbourhood in 2025. Relations with Bangladesh are strained; the debt-distressed Maldives reluctantly accepted a short-term liquidity inflow from an RBI swap after China cooled towards its request for aid. Nepal’s Prime Minister K.P. Sharma Oli has just signed a framework agreement with China to implement infrastructure projects under the Belt & Road Initiative. Struggling economically under Taliban rule, Afghanistan risks becoming a regional centre for narcotics trade and illegal migration, as does Myanmar to India’s east. Relations with Pakistan remain in cold storage.

These issues concern both India and Sri Lanka. An effective economic partnership in South Asia can serve as a model for others, bolster India’s Neighbourhood First Policy, and enhance India’s position as a regional power.

Conclusion

The slowdown of the Chinese economy and the shift, particularly by MNCs, from China to other, more competitive locations, have opened up business opportunities for latecomers to supply chains in the developing world. The available evidence suggests that Southeast Asia and some South Asian countries, such as India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, could benefit from the supply chain shift, particularly in labour-intensive segments. The shift is underpinned by geopolitics, as well as the availability of skilled and relatively low-cost labour and a large middle class. However, these factors carry constraints: Southeast Asia does not offer scale, and South Asia, which can, is a latecomer to trade-led regionalism, therefore constrained by policy barriers and infrastructure gaps.

Three policy implications arise from the analysis presented in this paper regarding the enhancement of India’s and the broader South Asia’s role in global supply chains. First, openness to trade and FDI inflows is fundamental for entering and deepening a country’s position in global and regional supply chains. The Trump reciprocal tariffs might be viewed as an opportunity for South Asia to implement comprehensive trade and FDI reforms, reduce red tape, and digitise business procedures to improve the ease of doing business and minimise corruption vulnerabilities. It may be prudent to reconsider the case for ‘big bang’ comprehensive reforms, as gradual, incremental reforms have yielded mixed results.

Secondly, countries should invest in trade-related infrastructure, such as transhipment ports, logistics services, and connectivity between ports and roads, to significantly reduce trade costs. In this context, enhancing the performance of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to attract both foreign and domestic investors, along with the clustering of business activities, is advantageous as trade and investment reforms may require time.

Third, concluding comprehensive free trade agreements with India’s neighbours, such as Sri Lanka, would help to reduce regional trade barriers and establish rules-based trade in the region amidst global uncertainty. In this context, India should consider time-bound fiscal and financial incentives to encourage the regionalisation of supply chains in its neighbourhood, similar to its own PLI scheme.

Author Brief Bio: Dr. Ganeshan Wignaraja is Professorial Fellow in Economics and Trade at Gateway House and Visiting Senior Fellow at ODI Global in London. He holds visiting appointments at the National University of Singapore and RIS in New Delhi. He is a member of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s Stakeholder Engagement Committee on monetary policy and financial stability matters. Previously, he served on the WTO Director-General’s Task Force on Aid for Trade during the WTO Doha Round and the Sri Lankan Prime Minister’s Task Force on the Indian Ocean. In a career spanning over 30 years in the UK and Asia, he has held senior roles in international organizations (including the Director of Research at the Asian Development Bank Institute in Tokyo, Chief Programme Officer at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London and a Visiting Scholar at the IMF in Washington DC), government (including Executive Director of the Sri Lankan Foreign Ministry’s think tank), and the private sector (including Global Head of Trade and Competitiveness at Maxwell Stamp PLC in London). He also worked at the Institute of Economics and Statistics at Oxford University and the OECD in Paris. He has a DPhil in economics from Oxford University and a BSc in economics from the London School of Economics.

References

Ahuja, Anil, “Changes in India’s Defense Technology Development Policies Over the Decade”, Article, Vivekananda International Foundation, https://www.vifindia.org/article/2024/may/29/Changes-in-India-s-Defence-Technology-Development-Policies-Over-the-Decade

Asian Development Bank (ADB), Asia Regional Integration Center, “Free Trade Agreements” accessed April 01 2025. https://aric.adb.org/fta

Baldwin, Richard; Freeman, Rebecca and Theodorakopoulos, Angelos, “Hidden Exposure: Measuring U.S. Supply Chain Reliance”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2023, September 28-29, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2_Baldwin-et-al_unembargoed.pdf

Das, Koustav, “India needs consistent reforms to remain fastest-growing economy: IMF’s Gita Gopinath”, India Today, January 16, 2024. https://www.indiatoday.in/business/story/imf-gita-gopinath-interview-world-economic-forum-davos-india-reforms-fastest-growing-economy-2489558-2024-01-16

Dhar, Biswajit, “India’s renewed embrace of free trade agreements”, East Asia Forum, February 21, 2022. https://eastasiaforum.org/2022/02/21/indias-renewed-embrace-of-free-trade-agreements/

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “Foreign direct investment trends and outlook in Asia and the Pacific 2023/2024”, December 15, 2023. https://www.unescap.org/kp/2023/foreign-direct-investment-trends-and-outlook-asia-and-pacific-20232024#

Irwin, Douglas “Dismantling the license raj: The long road to India’s 1991 trade reforms” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 25-2, January 2025.

Kathuria, Sanjay; Yatawara, Ravindra A. and Zhu, Xiao’ou, Regional Investment Pioneers in South Asia: The Payoff of Knowing Your Neighbors (English). South Asia Development Forum Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, November 18, 2021. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/172151637224905060/Regional-Investment-Pioneers-in-South-Asia-The-Payoff-of-Knowing-Your-Neighbors

Kawai, Masahiro and Wignaraja, Ganeshan, “Patterns of Free Trade Areas in Asia”, East West Centre, Policy Studies, No 65, 2013 https://www.eastwestcenter.org/sites/default/files/private/ps065_0.pdf

Rajan, Raguram. and Lamba, Rohit, Breaking the Mold: India’s Untraveled Path to Prosperity, Princeton University Press, 2024.

Wignaraja, Ganeshan, “Fostering Regional Trade Integration between South Asia and East Asia for COVID-19 Recovery” in South Asia’s Path to Resilient Growth, eds. Salgado, Ranil; Anand, Rahul, International Monetary Fund, December 23, 2022. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Books/Issues/2022/12/23/South-Asia-s-Path-to-Resilient-Growth-527427

Wignaraja, Ganeshan, “The Great Supply Chain Shift from China to South Asia?”, Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations, Paper No.34, July 2023. https://www.gatewayhouse.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Gateway-House-Paper_The-Great-Supply-Chain-Shift_2023.pdf

Wignaraja, Ganeshan. 2025 “India and UK Seal Historic Trade Deal After Brexit: Economic Gains for India” ODI Blog, 23 May 2025.

World Bank, “India: Becoming a High-Income Economy in a Generation”, Country Economic Memorandum, World Bank: Washington DC. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/400139d320ead96a0ec624d3608d9b56-0310012025/original/India-Country-Economic-Memorandum-2024-0227c.pdf

World Trade Organization, Economic Research and Statistics Division, “Information Note on Trade in Intermediate Goods: Fourth Quarter 2023”, 2023. http://wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/miwi_e/info_note_2023q4_e.pdf