On the occasion of 50th anniversary of ASEAN while creating a balance sheet of India-ASEAN partnership we look at the 25 years of missed opportunities for India – from the period 1967- 1992 and thereafter at 25 years of engagement – from 1993-2017, in an attempt to understand India and ASEAN engagement over the years, particularly in the context of the changing geo-politics of the Indo-Pacific region. The Paper begins with a brief snapshot of ASEAN and its partnership with India. In this Golden Jubilee year of the establishment of ASEAN and Silver Jubilee year of its dialogue partnership with India, this Paper endeavours to venture into the multi-dimensional nature of ASEAN and its multi-faceted relationship with India at large.

ASEAN: A Snapshot

Fifty years is usually not a long time in the lifetime of a nation-state. But for ASEAN, a regional conglomeration of ten separate nation-states in Southeast Asia, fifty years has spelled a transformational experience for the region as indeed also the world. Ever since its founding, the regional grouping apart from driving the regional conversations forward around multiple regional and global subjects in a more orderly and well-defined fashion, has injected a sense of predictability and pattern to the way regional multilateralism is conducted in this part of the world. In fact in time, it has evolved as the most institutionalised regional association in Asia. As a collective identity, the ASEAN has not only addressed a welter of issues within the grouping but projected a more potent force for action and bargaining when dealing with players and institutions exogenous to the region. In some ways, it may well be argued that the enduring and lasting success of ASEAN as a regional institution has been the primary reason why other regional entities have not quite proved to be as promising and as fulfilling as the Southeast Asian grouping, notwithstanding the different contexts and purposes for which they were founded in the first place. Perhaps it has something to do with the characteristic resilience of ASEAN as an organisation. When it started out, the Bangkok Declaration of 1967 chiefly had ‘economic, social, cultural, technical, scientific and administrative fields’ in mind apparently even as the underlying motive and the context may have been altogether different. Then the Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) in 1971 had reflected the shifting great power balance in wider Asia. Hallmark of a cautious and thinking institution, it had taken no less than almost a decade for ASEAN to meet at a summit level in 1976 when it accomplished the Declaration of ASEAN Concord and the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) with the latter formalising the core principle of non-interference as underpinning the terms of engagement among member states. Buoyed by their individual economic successes in the 1970s and 1980s, the ASEAN 6 had taken their economic agenda to a new level when they decided to establish ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA)

in 1992.

As Cold War eventually wound up, the ASEAN’s more formal initiative on regional security fructifying in the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) had once more been clearly demonstrative of the organisation’s innate ability to reinvent itself and retain its leadership role as the foremost ideologue of regional multilateralism. When the 1997 Asian financial crisis had scarred virtually all of ASEAN economies, the overtures to the three East Asian nations and shaping up of ASEAN Plus Three (APT) was an exercise emblematic of making virtue out of adversity. From shaping the contours of ASEAN Plus 3 to being at the core of the East Asian Summit, ASEAN has not only retained the reins of regionalism in its own hands, it has expanded its diplomatic weight and footprints from Southeast Asia to the broader East Asia and Asia Pacific. The 2007 Charter besides bestowing on the institution a legal personality, also sets it well on course to truly become an Economic (AEC), Political-Security (APSC) and Socio-cultural (ASCC) community.

Without doubt, ASEAN’s normative benchmarks as constituting renunciation of use of force, non-interference and peaceful settlement of disputes have served the region well for nearly five decades now. Southeast Asia once speculated as the ‘Balkans of the Orient’ has refused to fall apart simply not living up to its borrowed name, and thankfully so – unlike what befell the original Balkans in Europe unfortunately. Boasting of the world’s third largest market on the back of a population of 625 million people and with a combined GDP of US$ 2.6 trillion, ASEAN is already the 7th largest economy in the world projected to be the fourth largest by 2050. No wonder, in a glorious run over fifty years since 1967, the iconic grouping has transformed the region from one of battlefields to marketplaces! As EU increasingly gets weighed down by the post-BREXIT tremors and globalisation pushes back in the reverse, what better time than now to re-examine ASEAN and how it could perhaps carry the flag of regional multilateralism.

Balance-Sheet of

India-ASEAN Partnership

Transformation of India’s foreign policy from the rhetoric of ‘Look East’ to the action oriented ‘Act East’ has reiterated its focus on the extended neighbourhood in the Asia-Pacific. The ‘Act East’ policy was crystallised to underline the importance of East Asian neighbours of India and make them a priority in our foreign policy. It promises to inject new energy into India’s engagement with Asia in the economic, political and security domains. “It has widened the canvass by drawing Australia into India’s Eastern Strategy and the South Pacific back on Delhi’s political radar”1. In this most recent proposition to woo the Southeast Asian neighbours by reviving historical and civilisational ties and engaging in defence and security cooperation, India has raised alarms for the rival powers in the neighbourhood. Given the history of United States realpolitik of shifting alliances, priorities and commitments and its recent rebalancing strategy in the Asia-Pacific and the China’s rising influence in the region, the Southeast Asian countries are welcoming greater Indian involvement in the regional architecture of Asia. In the context of such a geo-strategic mix, they have been following interactions between China and the United States and thereby trying to maximize their strategic independence. In the shifting balance of power in the world politics, India’s Act-East policy emerges as a noteworthy characteristic determining the ‘Great Game’ politics in the Indo-Pacific.

India as a close friend and partner of ASEAN is equally affected by the developments in its extended neighbourhood. Rooted in deeper historical and civilisational ties, augmenting India-ASEAN relations have been the primary focus of our ‘Act East Policy’. In fact, India places ASEAN at the heart of its ‘Act East Policy’ and centre of its dream of an ‘Asian Century’. As ASEAN celebrates fifty years of its existence, India also celebrates 25 years of India-ASEAN Dialogue Partnership. In this relationship, we have graduated from a Dialogue Partner to Summit level interactions and finally to Strategic Partnership in recent times thereby learning lessons of deeper economic integration and comprehensive engagement with Southeast Asian neighbours. Given this background, the next section seeks to make an assessment of the Balance sheet of India-ASEAN partnership by dwelling upon the first 25 years of missed opportunities and the later 25 years of engagement and honeymoon period of India and ASEAN.

25 Years of Missed Opportunities

According to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, “ASEAN began in times of a great global divide, but today as it celebrated its Golden Jubilee, it shone as a beacon of hope; a symbol of peace and prosperity”2. “In 1967, when the whole region was seething with buzz of uncertainties, establishment of ASEAN prevented the ‘Balkanisation of Southeast Asia’, and established the thrust on search for common values, replacing conflict with economic, political, cultural and strategic cooperation”3.

Nevertheless, establishment of ASEAN was viewed with doubts in an ideologically polarised Southeast Asia where “intra-regional ideological polarisation and intervention by the external powers were marked features of geo-political landscape of Southeast Asia”4. This prevented the newly established regional community in Southeast Asia – ASEAN, to embrace India openly in spite of the cultural, religious and cvilisational linkages between the two regions. During the politics of Cold War, India-ASEAN relations were subjected to distrust and doubts about each other’s intentions and ideologies. “The narrative of India-ASEAN relations during the Cold War could be summarized as missed opportunities due to political mistrust, economic uncertainties and occasional military threats”.5

India’s opposition to the United States during its intervention in Vietnam also created suspicion in its expected role in ASEAN6. During the Cold War politics, India and ASEAN were in ideologically opposed camps. This was seen by India as a means to contain communism, which was on the rise due to the spill over from the Vietnam War. “While South East Asian nations had approached India as early as 1967 to join the ASEAN, India remained lukewarm to their overtures because of overall geopolitical situation in the region and the ongoing Cold War redux in Indo-China at that time”7. India’s support to Vietnam as opposed to the ‘hegemonic’ desires in Indo-China during 1960s resulted in the reciprocal loss of support from the United States. Opportunity cost was in the form of the United States President Johnson postponing the planned visit by Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to the United States. It further resulted in the cancellation of a planned visit by the United States President Ford to India a decade later, thereby widening the gap between India and ASEAN member countries irrespective of the geographical proximity and historical and cultural ties between the people of the two regions8.

Another case of lost opportunity during the first 25 years of the establishment of ASEAN was visible in the India’s support to the Vietnam’s backed Heng Samarin regime in Cambodia and its strategic ambitions in rest of Indo-China. This further alienated India’s place in the United States policy prescriptions and its approach towards ASEAN member states9. “After the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime, India recognized the new government and re-opened its Embassy in Phnom Penh in 1981 when much of the world shunned Cambodia”10. This turned out to be a major diplomatic miscalculation. The resultant strategy of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s cancellation of the scheduled discussions with ASEAN and internationally embracing the communist regime signified growing bitterness in India’s approach towards existing ASEAN members 11. The stalemate continued until the collapse of Soviet Union, when India became a Sectoral Dialogue with ASEAN in 1992 and established full Dialogue partnership in 1995.

Southeast Asia witnessed a major change in its political atmosphere in the aftermath of the Cold War – especially after the settlement of the Cambodian crisis and change in the ASEAN’s perception towards Vietnam as a potential ally. This contributed in a big way to the emergence of a strong strategic and defence ties between India and ASEAN member countries. This period also saw “the beginning of India’s Look-East Policy which was intended to reach out to the countries of East and Southeast Asia which had been neglected by India in spite of cultural, religious, geographical proximity and historical links”12. With the launching of India’s economic liberalisation programme in 1991, ASEAN came to be identified as being ‘pivotal’ to India’s policy in the Indo-Pacific region.

25 Years of Engagement

Post Cold War era witnessed a significant increase in the engagements between India and ASEAN member countries. They have leveraged from the large potential in synergies between their economies13. “The resolution of the Cambodian conflict brought about a fundamental change in Indo-ASEAN relations”14. There was an expansion in the membership of ASEAN to include all countries which are physically part of Southeast Asian region – irrespective of their ideological orientations and regime types. Furthermore, “the emergence of China as an ‘economic dynamo’ and its increasing trade and commercial interests and cooperation with ASEAN countries has been another motivating factor for India to enhance its own linkages with the ASEAN”15.

India-ASEAN partnership has been a noteworthy feature and provides significant underpinning to the ‘Act East Policy’ today. Though, actually envisaged at “bolstering strategic and economic ties” with Southeast Asian countries, it aims at tapping the region for greater investment and connectivity16. According to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, “our ties with South East Asia are deep rooted. Strengthening relations with ASEAN nations is an important part of our ‘Act East’ policy. It is central to our dream of an Asian century, where India will play a crucial role”. With this background, the following section looks at the political and security engagements; economic cooperation; physical connectivity; people to people relations and development partnership between India and the countries of the Southeast Asian region.

– Political and Security Engagements

The up-gradation of the relationship into a Strategic Partnership in 2012 was a natural progression to the ground covered since India became a Sectoral Partner of the ASEAN in 1992, Dialogue Partner in 1996 and Summit Level Partner in 200217. India is also an active participant in several security based ASEAN forums like the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting + (ADMM+) and Expanded ASEAN Maritime Forum (EAMF). India has set up a separate Mission to ASEAN in Jakarta in April 2015 with a dedicated Ambassador to strengthen engagement with ASEAN and ASEAN-centric processes.18 The ASEAN Post Ministerial Conference (PMC) 10+1 Sessions with The Dialogue Partners also provides opportunity for ASEAN and the Dialogue Partners to review their cooperation over the past year and further deepen their cooperation, strengthen their engagement, as well as to ensure the effective implementation of the respective Plans of Action to elevate cooperation in all areas. These meetings also served as avenues for the Ministers to exchange views on regional and international issues of mutual interest and concern, collectively and constructively address global developments and existing, emerging and trans-boundary challenges and strengthen development cooperation with ASEAN19. Measures like the signing of a “Joint Declaration for Cooperation to Combat International Terrorism,” maritime exercises with the navies of ASEAN countries, information-sharing initiatives, and defense agreements with individual ASEAN countries have added a new dimension to ASEAN-India relations.20

– Economic Engagements

For enhancing economic ties with ASEAN member countries, India signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in goods in 2009 and an FTA in services and investments in 2014 with ASEAN. The ASEAN-India Free Trade Area has been completed with the entering into force of the ASEAN-India Agreements on Trade in Service and Investments on 1 July 201521. Apart from this, India has a Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement with various countries of the ASEAN region. This has resulted in concessional trade and a rise in investments22.

The ASEAN members and India together consist one of the largest economic regions “with a total population of about 1.8 billion and a combined GDP of $3.8 trillion. ASEAN and India together form an important economic space in the world”23. It is currently India’s fourth largest trading partner, accounting for 10.2 per cent of India’s total trade. India is ASEAN’s seventh largest trading partner. “India’s service-oriented economy perfectly complements the manufacturing-based economies of ASEAN countries. There is, however, considerable scope for further growth”24. As per the Ministry of External Affairs report, “India’s trade with ASEAN has increased to US$ 70 billion in 2016-17 from US$ 65 billion in 2015-16. India’s export to ASEAN has increased to US$ 31.07 billion in 2016-17 from US$ 25 billion in 2015-16. India’s import to ASEAN increased by 1.8% in 2016-17 vis-à-vis 2015-16 and stood at US$ 40.63 billion. Investment flows are also substantial both ways, with ASEAN accounting for approximately 12.5% of investment flows into India since 2000″.25

ASEAN and India have been also working on enhancing private sector engagement. ASEAN India-Business Council (AIBC) was set up in March 2003 in Kuala Lumpur as a forum to bring key private sector players from India and the ASEAN countries on a single platform for business networking and sharing of ideas. AIBC is an organization that builds relationship between India and ASEAN countries to foster stronger ties in trade and economy. It was conceptualized to provide an industry perspective to the broadening and deepening of economic linkages between ASEAN and India26. The AIBC consists of eminent Leaders of Business in ASEAN Member States and India. They meet on the sidelines of ASEAN-India Economic Ministers’ Meeting27.

– People to People Relations

People-to-people exchanges continue to remain an important pillar of India-ASEAN relations today, and “we aim to expand them through various initiatives, such as through the exchange of artists, students, journalists, farmers and parliamentarians, as well as a multiplicity of think-tank initiatives”28. People of the two regions connect not only through political and diplomatic means, but there are historical and civilisational linkages. Ramayana and Mahabharata – two great Indian mythologies find a meeting ground in ASEAN region. Similarly, Buddhism and Bollywood are two great popular cultures capturing the imagination of the people of the region. Besides, a large number of Indian Diaspora in Southeast Asia, provide a fertile ground for linking of people and culture since long. The cultural and intellectual exchanges between the people of two region has enabled us a better understanding of the relations between India and ASEAN. At the level of the Government, several activities leveraging people-to-people connectivity are held annually to increase interaction between India and ASEAN Community. These include, ASEAN-India Network of Think Tanks, Exchange of Parliamentarians, ASEAN-India Media Exchange Programme, Students Exchange Programme, ASEAN-India Eminent Persons Lecture Series, Special Course for ASEAN Diplomats and their training at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) in New Delhi29. Recently held India-ASEAN Youth festival in August 2017 is an example of identifying Youth as cultural ambassadors for a deeper understanding of socio-cultural linkages between the two regions.

– Physical Connectivity

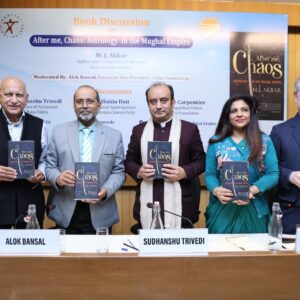

ASEAN-India connectivity has been a priority for India and central to its ties with ASEAN. In 2013, India became the third dialogue partner of ASEAN to initiate an ASEAN Connectivity Coordinating Committee-India Meeting. While India has made considerable progress in implementing the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway and the Kaladan Multimodal Project, issues related to increasing the maritime and air connectivity between ASEAN and India and transforming the corridors of connectivity into economic corridors are under discussion. A possible extension to India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway to Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam is also under consideration. A consensus on finalising the proposed protocol of the India-Myanmar-Thailand Motor Vehicle Agreement has been reached. This agreement will have a critical role in realizing seamless movement of passenger, personal and cargo vehicles along roads linking India, Myanmar and Thailand. PM announced a Line of Credit of US$ 1 billion to promote projects that support physical and digital connectivity between India and ASEAN and a Project Development Fund with a corpus of US $ 50 million to develop manufacturing hubs in CLMV countries at the 13th ASEAN India Summit held in Malaysia in November 201530. India-ASEAN Connectivity Summit was also organised in December 2017 in New Delhi. According to M. J. Akbar, “While the road component is progressing apace, maritime connectivity – the mainstay of our historical trade relations, requires urgent modernisation in the context of current geopolitical realities”. According to him, “connectivity will address investment opportunities in ASEAN-India Islands Connectivity and discuss the challenges that need to be addressed in order to sustain the progress”31. To add further, the need for not only physical connectivity but digital connectivity has also been emphasised.32

– Act East and North-Eastern Region of India

The North-eastern India as a region is landlocked, sharing most of its boundary with neighbouring countries of South and South East Asia. It is supposed to be an essential factor in extending linkages with the Southeast Asian countries and critical for India’s ambitious Act East policy to succeed. Given its strategic location, bordering on Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Myanmar and China, the region could be developed as a base for India’s growing economic links. “Though considered as the country’s most economically laggard regions, no other region in India can rival it in terms of the availability of natural resources and its potential for international connectivity”33. Over the years, “geo-political distancing of the region from its main port of Kolkata, combined with economic insulation, has weighed down the Northeast’s economy”34. Nevertheless, India has been trying to bridge this isolation through the ‘Act East’ policy by promoting trade and physical connectivity through its north-eastern borders with Southeast Asian region.

–Development Partnership with CLMV Countries

Serving as a platform for deepening and strengthening its relationship with ASEAN, the CLMV countries (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam) have also been a special focus area for India. “At a time when manufacturing facilities are shifting to lower-cost economies, both India and the CLMV countries enjoy an advantage. With ‘Make in India’ emerging as a key campaign for manufacturing, developing new global value chains in partnership with the four least-developed economies of ASEAN would bring benefits to both sides”35. Over the years, special focus has also been on building up of the road, rail and waterways network for developing the infrastructural links between the North-east India and its engagement with the Southeast Asian countries. India has set up a Project Development Fund for CLMV countries and EXIM Bank also provides lines of credit for projects in power, irrigation and railways. Besides, facilities for English language training, entrepreneurship development, and IT skills have also been set-up by India for capacity building in these countries.

Conclusion

India-ASEAN relations are a critical component of India’s overall external engagement with the Indo-Pacific and beyond. A balance-sheet of India-ASEAN relations over the years reveal two and a half decades of missed opportunities resulting from the ideological misgivings and conflicts in the internal politics of the countries of the region. However, the end of Cold War and collapse of Soviet Union was a critical juncture in the world politics. It brought about a major shift in the balance of power in Southeast Asia also bringing about transformation in the internal political dynamics of the countries of the region. The end of Cold War also marked a turning point in India-ASEAN Relations in the wake of liberalisation and market oriented reforms. In the changing architecture of global politics, India adopted itself to the emerging world order, thereby beginning a new chapter as the ‘Look East Policy’ now being transformed as ‘Act East Policy’ in its foreign policy paradigm. For the last 25 years – driven by geo-strategic and economic realities, India and ASEAN moved on the path of strong political and diplomatic engagements followed by economic and strategic partnership between countries of the region.

Encompassing shared heritage of centuries old civilisational ties – India and ASEAN have provided foundation to the close cultural and historical bonds, upon which lays the edifice of deeper economic and strategic partnership between the countries of the region. To conclude, in the words of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, “for the near future, South and South East Asia will be the growth engine of the world. Hence, building connectivity with ASEAN is a key objective for India”.

References:-

1 Rajamohan (2015), Modi’s World: Expanding India’s Sphere of Influence, Harper Collins.

2 Key Points at Prime Minister’a Address at 12th East Asia Summit in Manila, 14 November 2017. Online Edition.Accessed on 10 December 2017. URL: https://www.narendramodi.in/key-points-from-prime-minister-s-address-at-the-12th-east-asia-summit-537799

3 Speech of M. J. Akbar at the Regional Conclave on ASEAN@50 and India – ASEAN Relations, 7-8 December 2017, Bengaluru.

4 Acharya, Amitav (2001), Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia, Routledge. p. 4

5 The Diplomat (2017), “Revisiting ASEAN-India Relations”. Online Edition.Accessed on 11 December 2017. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/revisiting-asean-india-relations/

6 Clark, Helen (2016), “Why Vietnam has India in its Side” Lowy Institute.Online Edition.Accessed on 11 December 2017. URL:https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-vietnam-has-india-its-sights

7 Anand, Vinod (2017),”India-Vietnam Defense and Security Cooperation”, Vivekanand International Foundation.Online Edition.Accessed on 10 December 2017. URL: http://www.vifindia.org/article/2017/may/12/achievements-india-vietnam-defence-and-security-cooperation

8 Brewster D (2009),The Strategic Relationship between India and Vietnam. Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL:

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/13058/1/Brewster,%20D.%20India%27s%20S trategic%20Partnership%20with%20Vietnam%202009.pdf

9 Mohammed Ayoob (1990), India and Southeast Asia: Indian Perceptions and Policies, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp 53-72.

10 Ministry of External Affairs (2017), India-Cambodia Relations, Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December 2017. URL: http://www.mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/1_Cambodia_November_2017.pdf

11 Brewster D (2009),The Strategic Relationship between India and Vietnam, pp. 8.

12 Ahmad, Asif (2012), India – ASEAN Relations in 21st Century: Strategic Implications For India – Analysis, Eurasia Review. Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL:

http://www.eurasiareview.com/09072012-india-asean-relations-in-21st-century-strategic-implications-for-india-analysis/

13 Anand, Mohit (2009), India-ASEAN Relations: Analysing Regional Implications, Institute of Peace and Conflict Sudies Report 72. Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL:

http://www.ipcs.org/pdf_file/issue/SR72-Final.pdf

14Ahmad, Asif (2012), India – ASEAN Relations in 21st Century: Strategic Implications For India – Analysis, Eurasia Review.

15 Hong, Z. (2006), India’s Changing Relations with ASEAN: From China’s Perspective, The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 20(2), pp. 141-170. Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23257942?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

16Trivedi Sonu (2014), “Act East Policy vis-a-vis Pivot to Asia”, The Global New Light of Myanmar, November 16.

17 Ministry of External Affairs, India-ASEAN Relations. Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL:

http://www.mea.gov.in/aseanindia/20-years.htm.

18 Ibid.

19 ASEAN.Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL:

http://asean.org/chairmans-statement-of-the-asean-post-ministerial-conference-pmc-101-sessions-with-the-dialogue-partners-3/

20 The Diplomat (2017), “Revisiting ASEAN-INDIA Relations”.Online Edition.Accessed on 12 December 2017. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/revisiting-asean-india-relations/

21 Indian Mission to ASEAN.Online Edition.Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.indmissionasean.com/index.php/asean-india

22 The Diplomat (2017) “Revisiting ASEAN-India Relations”,Online Edition. Accessed on 15 December. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/revisiting-asean-india-relations/

23 IDSA (2016), “India ASEAN Approach”.Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: https://idsa.in/idsanews/india-asean-approach_080416

24Pant, Harsh V, (2017), “The ASEAN Outreach”, The Hindu, November 17.

25 Ministry of External Affairs, India-ASEAN Relations. Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.mea.gov.in/aseanindia/20-years.htm

26ASEAN-India Business Council.Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.asean-india.org/

27Indian Mission to ASEAN.Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.indmissionasean.com/index.php/asean-india

28Pioneer (2017), “ASEAN: sharing Values and Common Destiny”, September 6. Online Edition.Accessed on 14 December. URL:

29Indian Mission to ASEAN.Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.indmissionasean.com/index.php/asean-india

30 Ministry of External Affairs, India-ASEAN Relations. Online Edition.Accessed on 13 December. URL: http://www.mea.gov.in/aseanindia/20-years.htm

31 Assam Tribune (2017), “Connectivity Central to ties with India”. 12 December. Online Edition.Accessed on 15 December. URL: http://www.assamtribune.com/scripts/detailsnew.asp?id=dec1217/at061

32 Speech by Hon Minister for Electronincs & Information and Technology, Ravi Shankar Prasad at Valedictory Session on India-ASEAN Partnership@25, Kalinga International Foundation, 13 December 2017.

33 De, Prabir (2017),”Can Act East Address Northeast India’s Isolation?”.Online Edition.Accessed on 16 December. URL: http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2017/10/27/can-act-east-address-northeast-indias-isolation/

34 Ibid.

35 Banerjee Chandrajeet (2017), “From Look East to Act East”, The Hindu Business Line, February 26.Online Edition.Accessed on 16 December. URL: http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/developing-new-global-value-chains-in-partnership/article9560295.ece

(Ms. Sonu Trivedi teaches Political Science at Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi.)

(This article is carried in the print edition of January-February 2018 issue of India Foundation Journal.)