Since India gained independence in 1947, the Indian economy passed through various challenges. On the eve of independence,the size of its population was 360 million, and the literacy level was just around 12 percent. Presently, the population has touched 1.35 billion, and literacy level has jumped to 74 percent. Its GDP in 1950 was around $30.6 billion. By 2020 beginning, the GDP rose to $3.202 trillion. The Indian economy is now the fifth-largest in the world in terms of nominal GDP, and third largest by Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) (Mohan, 2020).

The Indian economy adopted different models for development over the years. During the 1950s, the main emphasis was on having a planned economy/mixed economy. Industrialisation began mainly in the public sector, and efforts were made to become self-sufficient in food grains production. Owing to those efforts, in agriculture India is surplus in food grains production. The second phase of the Indian economy started with economic reforms initiated during the 1980s and accelerated from 1990s onwards.

In these phases of development of the Indian economy, there is one other country, i.e. China that can provide a benchmark for comparison. In 1949, China’s population was 540 million, and literacy level was 20 percent. In 2019, China had a population of 1.39 billion, and literacy is around 85 percent. Both India and China have significant reservoirs of human resources. The difference is only in types of government. In China, the government is centralised and coercive to achieve targets, while it is democratic in India. Economic reforms started in both countries during the 1980s.

The third phase of the Indian economy started in 2014 with the present regime under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The government gave various energetic slogans and unleashed a new resolve to create a stronger economy. The NITI Aayog released in 2018 the ‘strategy for New India @ 75’, which is the corollary of Prime Minister’s slogan “New India by 2022”. The main message was to ensure balanced development across all the states with collective efforts and effective governance. The strategy covered as many as 41 sectors for balanced growth with few strategic priorities, and set the target of $4 trillion economy by 2022 (additional 1 trillion of GDP in three years) (Aggarwal, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the PM gave another call of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (Self-Reliant India) movement supported by the ‘Vocal for Local’ (Goyal, 2020). The other slogans like Make in India, Digital India, DBT, and Clean India are meant to impact the economy in future positively.

Since the economy was noticeably suffering a slowdown in January 2020, the revised GDP growth estimates came downwards to 5 percent, which became a cause of concern. India’s general government deficit, which was estimated at a whopping 7.5% to 9% of the Gross Domestic Product in 2019, is mopping up most of the net financial savings of the households, which are estimated at around 11% of the GDP. When the economy was not under stress, the gap between the combined deficit and total household savings was 6 to 8% of the GDP, which is now around 2%; and therefore, the private sector is comparatively starved of funds. (Montek, 2020)

Further, two immediate factors which impacted the Indian economy are, firstly, Covid- 19 pandemic, and secondly, the prospect of India- China military face off spilling over to the realm of economics. To put things in perspective, in terms of per capita income, China is ahead of India. China is an upper-middle-income country. The per capita income in China is $10,276 against $2,104 for India. China and India are trading in large volumes, with India suffering a huge trade deficit.

In six months Covid-19 has already caused a slowdown in global economies. The cost of economic disruption caused globally by the pandemic has been estimated between $9 trillion and $33 trillion. The global consulting company Mckinsey has emphasised that the cost of preventing future pandemics would be much less than the cost of suffering future pandemics. Rightly observing that the pandemic has exposed the weaknesses in the walls of infectious-disease- surveillance and-response capabilities, it rues that investments in public health and other public goods are solely undervalued; investments in preventive measures, where success is invisible, even more so. The attention should not shift once the pandemic recedes, thinking that the world is free to have its way for another one century till such a pandemic hits again. It is imperative to understand that this pandemic is neither the last one nor is there any guarantee that pandemics will not come with higher frequency. According to the report prepared by Mckinsey, global spending of $30-$220 billion over the next two years and $20-$40 billion annually after that could substantially reduce the likelihood of future pandemics.

Mckinsey offers a candid caveat that these are high-level global estimates with wide error bars and that they do not include all the costs of strengthening health systems around the world. The wide gaps prevail on health expenditures as percentage of GDP across countries. In India, health expenditure as percentage of GDP is 3.5%, in China it is 6.5%, and in developed countries like USA, it is 17.7%. In India, the centre and state budget allocation to health is around 4-5% whereas other countries allocate around 8-10% of the budget to health care.

India’s present GDP per capita is around $2,104. China’s per capita GDP is $10,261, and that of the US is $54,795. The Indian economy will have to move forward on a fast track. China’s GDP was 5% of the $GDP in the 1980s, but today it is almost 60% of the US GDP (Nominal). As per the World Bank classification, India falls in the lower-middle-class country with GNI per capita ranging between $1026-3995, while China is an upper-middle-class country with GNI per capita ranging between $3996-12,375. By way of an illustration of the objective ahead, the United States of America and a large number of other countries fall under the high-income countries group with GNI per capita more than $12,376. India’s share of world GDP is less than 4%, whereas it is around 15% in the case of China and 23.6% in the case of the USA. Indian economy needs a determined, consistent, big push to scale itself to a much higher and bigger operating economic platform and to come out of economic slowdown that emerged due to pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic, having inflicted direct disruption to production, supply chain, financial impact on firms and financial markets; unemployment; the stress of the banking systems due to the moratoria on repayments along with NPAs; a deadly blow to hospitality, tourism and transport sectors, combined with the essential cash and kind subsidies and doles to mitigate the pandemic stress on the poor in particular, and all sectors of the economy in general has the potential to put Indian economy in a tailspin. However, timely interventions by a decisive and a resolute leadership combined with the tenacity and fighting spirit of the Indian industries, in general, has the potential of converting the pandemic tragedy into a global opportunity to lead the other countries through a process of faster recovery.

India’s tax to GDP ratio is around 10%; while most developed countries have tax to GDP ratio of 30%. Indian economy needs resources to strengthen the health sector leadership, healthcare financing, health workforce, medical products and technologies, information and research and service delivery, which is the WHO prescription for achieving the desired outcomes of the improved health level and equity, responsiveness, financial risk protection and improve efficiency.

Banking is the backbone of any planned economic resurgence. There has been a policy trend to undertake public expenditure by the government, either through direct spending or through facilitating bank credit for private investments. Although attention has been paid in the recent past to the non-productive assets accumulated in the banks, and some remedial measures are underway, there has been an indiscreet proportion of lending, at times without adequate diligence, with the sole purpose of accelerating growth.

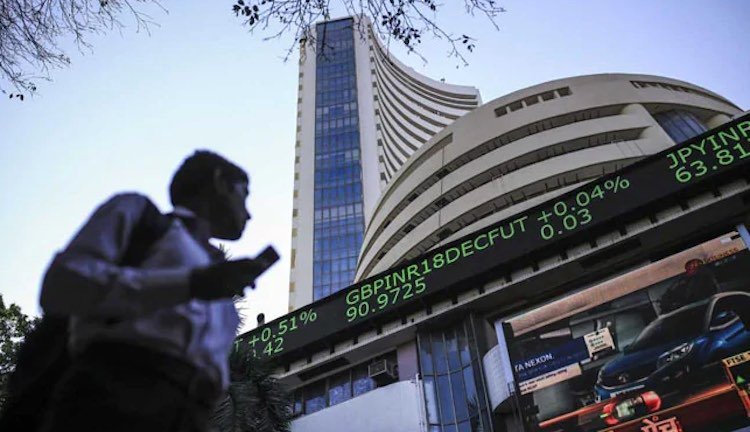

As growth in itself has become a politically flagged yardstick of achievement, the direct or indirect government ownership of the banks has contributed to dilute their essentially commercial and business-like operations. The public ownership has created an environment where market discipline is perceptibly weak, and where the regulators remain circumscribed. Over decades, investment entities, financial institutions and non- banking financial companies have been used to support vague and extraneous objectives underwriting the government’s disinvestment targets, preserving employment in public enterprises, contributing assistance to states based on the political clout of the representatives, intermittently providing artificial support to stock markets, and occasionally ignoring lapses in due diligence.

Special attention is required to ensure sound health and reliability of the government banking sector, which needs to set up excellent benchmarks for private banks. However in India, it is the other way round. In public perception, the depositors are no longer as confident of the nationalised banks for the security of their deposits, as they used to be a decade earlier. It is interesting to note that between March 2018 and March 2019, when the safety perceptions got ruffled, the deposits in private banks exceeded those in the nationalised banks. As against INR 4.8 trillion deposits in private banks, the government banks secured only INR 2.3 trillion of deposits after netting out the deposits of IDBI upon its reclassification as a private bank. Even the foreign portfolio investors preferred private banks. However, the nationalised banks still outperform the private banks in return of assets and return on equity (Patel, 2020). In 2019-20 the government infused INR 70,000 crore into public sector banks to boost credit for a strong impetus to the economy.

Thanks to an increasing realisation of the government about the need to tackle the burning issue of non-productive assets (NPAs) of the banks and emphatic insistence upon provisioning, there has been a reversion to the immensely needed working culture of securing the credit with strictest due diligence. During this pandemic time, many accounts would turn NPAs, especially those which were already in stress. Mergers and other administrative initiatives tend to increase the productivity of nationalised banks, which otherwise suffer from far lower revenue per employee as compared to their counterparts in private banking. It is a matter of grave concern that the amounts swindled through frauds have been ten times more in the nationalised banks as compared to their counterpart private banks.

It is excruciating, but a very welcome development for future reforms from the government, as well as the regulator. Reported cases of fraud of around INR 10 billion in 2018 multiplied exponentially thereafter (RBI-December 2019 Financial Stability Report UP 32), and the entire machinery has started the much-awaited sanitisation by getting after the cases of fraud hidden under the cloak of non-productive assets of the banks. This will hopefully make the banking sector emerge more robust anti-corruption measures. The troubled shadow banks saw signs of stimulus when the government in mid-May announced INR 3 trillion of collateral-free loans to the nation’s small businesses and INR 705 billion special credit loans to non-bank financiers.

Another moot point in public spending is that of the systemic leakages that take away a substantial part of the benefits that every unit of input must seek to achieve in the process of pump- priming the economy. Though bona fide and active initiatives have been taken, the leaking pipes have neither been replaced nor adequately repaired. The inevitable result is that more money is being pumped into the leaking pipes, and more the money pumped in, much more is the leakage. There is hardly any worthwhile quantitative comparison data between what the NITI Aayog has been able to achieve and improve upon and what the Planning Commission of India had lacked in the process of pumping funds into the leaking pipes operated both by the Centre as also by the States, which enjoyed substantial autonomy in operating the leaky system. Like the rest of the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has struck at the roots of almost all market forces, throwing various ongoing trends topsy-turvy. A demand-driven economy substantially catering to domestic consumption has suddenly reversed into a surplus capacity economy with the market forces of demand suffering a free fall on account of curtailed consumption levels.

Nothing can generate more demand than a firm resolve towards creating an Atmanirbhar Bharat. “The five pillars of Atmanirbhar Bharat – Economy, Infrastructure, System, Demography and Demand are aimed with a bird’s eye view on all the sectors and sections of society alike. Infrastructure, as an identity of the country; System, to bring in technology-driven solutions; Vibrant Demography; and, demand, tapping the demand- supply chain optimum utilisation of resources” (Yojana, July 2020). The Prime Minister has announced a unique economic and comprehensive package of INR 20 lakh crore, equivalent to 10% of India’s GDP, to support the five pillars of Atmanarbhar Bharat, calling upon the people to become vocal for our local products, and the industry to make the local products turn global in terms of production standards, quality and marketing.

Being self-reliant is critical for the growth strategy of Indian economy and to make it more export-oriented. Just taking note of India’s trade flow with China for an example, the imports by India from China stood at $73.3 billion, much higher than India’s exports to China pegged at $16.7 billion, leaving India’s trade deficit with China at the staggering level of $53.6 billion. The manufacturing sector in India could not grow as fast as compared to China and South Korea. In China and India, the economic reforms started during the 1980s onwards. During the period from 1961 to 2018, China grew by more than 10% in 22 years while India could never cross that mark even for a single year. The miracle of industrial growth happened in China by foreign direct investments in the selected regions on an experimental basis, the SEZs (Special Economic Zones) developed with foreign investments. Moreover, the state-owned enterprises at the local level of cities and villages known as TVEs linked to markets directly became ancillary industries. The labour laws became flexible and investments in the enterprises by the locals were encouraged. The legal system in China did not protect private property rights, and land acquisition is still not a hurdle as it is in India for setting industrial units. Gradually, the Chinese manufacturing sector shifted from labour intensive to capital intensive.

Much more worrying is the nature of India’s imports such as capital goods like power plants, telecom equipment, steel projects; intermediate products like pharmaceutical APIs, chemicals, plastics engineering goods; and finished products like fertilisers, refrigerators, washing machines, air conditioners, telephones etc. Low-cost consumer goods meeting every human need at the micro- level manufactured in China have invaded the Indian markets and have given a severe jolt to the Indian traditional and modern manufacturing sectors.

In India, the manufacturing sector always remained under the protection of the state. High import tariffs, inflexible labour laws, protection to small industries and inefficiency in state-owned enterprises could not create a milieu for the development of a competitive manufacturing sector. The industry, with particular emphasis on SME, will have to shed its internal inefficiencies fundamentally caused by the complacent, unprofessional, and hereditary ownerships-cum- management. Time has come when the increasing international competition will not allow the industry the luxury it has enjoyed so far, of passing on the cost of its inefficiencies to the consumers, who opt for products with higher quality at a much lesser cost.

Efforts to make the Indian MSMEs (Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises) competitive globally leave much to be desired. MSMEs contribute as much as 30% of the GDP and hence become a top priority. Presently, one of the welcome steps to support viable MSMEs in the face of their destabilisation due to the Covid-19 pandemic is the Reserve Bank of India stepping in to restructure the advances to this priority sector.

With a liberal classification on August 6, 2020, raising the aggregate exposure limit to the borrower INR 25 crore as on March 1, 2020, with a few more conditions, RBI has stepped in to benefit their accounts which may have slipped into NPA category. Similarly, the RBI has allowed banks to reckon the funds infused by the promoters in their MSME units through loans under Credit Guarantee Fund Trust for Micro and Small Enterprises / Distressed Assets Fund as equity/quasi-equity from the promoters for debt-equity computation. Further, the Indian economy can leapfrog ahead of others by dint of a creative policy on innovation. India’s Science, Technology and Innovation Policy of the year 2013 cater to the three pillars of talent, technology and trust, aimed at orienting public procurement towards innovative production.

India has a large population; some feel that it is a liability. A large population is not altogether a liability if it is converted into an economy’s strength. It creates much consumption-related demand; and if made employable and productive, it creates a massive tailwind for the economy to push it to grow at a faster pace. The issue is squarely related to the productivity of our labour, and value-added per average labourer in the process of production, which adds on to the Gross Domestic Product. It is a matter of concern that the value-added per worker in India is just about 10% of a US worker. China’s labour productivity in terms of value-added per worker is 2 ½ times more as compared to India. A two-pronged approach of skilling India’s labour force and providing it with the requisite resources is a prerequisite to increase the value-added per worker, thereby increasing the gross domestic product of India. Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojna operated by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (PMKVY) has the potential of giving a quantum jump to the gross national product by increasing the productivity and value-added per worker far beyond the present levels. There is a dire need to upgrade the skills of the Indian labour force to international standards by involving the industry for developing the necessary framework, curriculum and quality benchmarks.

The prioritisation of relevant skills should be left to the industry for meeting their demand, with a clear idea on those skills which can have a catalyst effect and multiply productivity to a geometrical growth. Though the National Skill Development Corporation boasts of having trained more than 5 million students in India, the qualitative skilling evaluation would not only capture the total numbers but essentially the increase that it has caused in the value addition per trained worker as compared to an untrained one. The government of India has identified high priority sectors for imparting skills with an eye upon fast track results as a part of Make in India initiative, where the economy has still miles to go ahead.

Agriculture and allied activities are already areas of specific focus because even though the contribution of primary sector to the GDP has come down substantially over the years, still about 70% of farm households in India own less than 1 hectares of land, and about 85% of the farm households own less than 2 hectares of land. Livestock and other allied agricultural activities which are required to supplement the income arriving from core agriculture require a revolution to take the primary sector to the next higher level of productivity and value addition. Indian agriculture made rapid progress in terms of production, but certain geographical constraints and lack of market orientation make it less competitive relatively to countries like China.

The Indian and Chinese agrarian economies are two ancient economies of the world. In both nations, a massive number of farmers depend upon agricultural income for survival. China has an advantage in irrigation when compared to Indian agriculture. India is the land of monsoons, where torrential rainfall is concentrated in a concise period of the year; whereas, in China, the average rainfall (at least in the more settled parts of the country) is somewhat more evenly distributed over the year. Reservoir storage of water supply in China for irrigation is almost five times that of India. Chinese agriculture productivity started improving since the 1980s when the shift came from collective farms to household responsibility farming. Chinese rice productivity is two times more than that in India. The share of agriculture in GDP in China is 7.11 percent, and in India, it is 15.4 percent. Percentage of persons employed in agriculture in China is 25.1, and in India, it is 42.39 percent as large inequality prevails in land ownership in India. (Bardhan, 2011) For the production of high-value crops, contracts between farmers and corporates are more successful in India than in China, especially in dairy and food processing. Market liberalisation in agriculture came in China after de-collectivisation. The compulsory quota and procurement systems have been abandoned by the government. In India, recently at the time of the pandemic, special packages have been designed for the agriculture sector and certain legislations have been amended to make the market free from state control. The Essential Commodities Act is being amended to help the farmers generate higher incomes by deregulating agriculture foodstuffs including cereals, edible oils, oilseeds, pulses, onions and potatoes etc. No stock limit applies to processors or value chain participants, with a few conditions, and further, it has been decided to impose stock limit under rare circumstances like national calamities, famine etc. as a price intervention by the state. The ordinances namely The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020, and The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement Price Assurance and Farm Services Ordinance, 2020, have been promulgated with a focus on the rural economy. The implications of various initiatives envisaged through these legislations has evoked much interest and are being intensely debated by various stakeholders. The resistance to these amendments from the farmer unions in many states is a big challenge to the government.

The Indian economy has indeed made substantial progress in the field of governance through re-engineering of business processes, technology and data analysis. The CEO of NITI Aayog informs that the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) has been implemented across 437 schemes, and helped to save INR 83,000 crore till date. He further discloses that its implementation has led to 2.75 crore duplicate, fake or non-existent ration cards being deleted, and 3.85 crore duplicate and inactive consumers for Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) subsidy being eliminated. Blockchain technologies can improve India’s prospects at ease of doing business rankings, elimination and resolution of litigation arising out of contractual obligations, compromises in quality control, and others. The Goods and Services Tax (GST), though still under the process of stabilisation, has added 3.4 million new indirect taxpayers. There is an imperative need to focus upon the application of Artificial Intelligence in the fields of agriculture, health care and education in the Indian economy.

As the Indian economy gears up on a fast track of growth, the conflict between “development” and “environment” will surely become more intense. The central and state ministries of environment will have to play a far more proactive role to ensure that development and ecological concerns are balanced for not only increasing the GDP but also for ensuring long-term sustainability through a pollution-free life. “If development is about the expansion of freedom, it has to embrace the removal of poverty as well as paying attention to ecology as integral parts of a unified concern, aimed ultimately at the security and advancement of human freedom. Indeed, important components of human freedoms-and crucial ingredients of our quality of life-are thoroughly dependent on the integrity of the environment, involving the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the epidemiological surroundings in which we live” (Dreze & Sen, 2013).

These are indeed challenging times. It is time for tough decisions, sound strategy, and a zero error implementation to be ahead of others in the changing global scenario.

*Sarvesh Kaushal is a retired Bureaucrat. He is a former Chief Secretary of Government of Punjab (India).

References:

- Ahluwalia, Montek Singh (2020): Backstage: The story behind India’s High Growth Years, Rupa Publications, Delhi, pp

- Patel, Urjit (2020): Overdraft: Saving the Indian Saver, Harper-Collins Publisher, Delhi, pp

- Kant, Amitabh (2018): The Path Ahead: Transformative Ideas for India, Rupa Publications, Delhi, XVII.

- Dreze, Jean & Sen, Amartya (2013): An Uncertain Glory: India & its Contradictions, Penguin Books, India, pp

- McKinsey & Company. “Not the Last Pandemic: Investing Now to Reimagine Public-Health Systems.” Https://Www.mckinsey.com/~/Media/McKinsey/Industries/Public and Social Sector/Our Insights/Not the Last Pandemic Investing Now to Reimagine Public Health Systems/Not-the-Last-Pandemic-Investing-Now- to-Reimagine-Public-Health-Systems-F.pdf, July

- Guruswamy, Mohan (2020): “We are trysting with destiny”. The Economic Times, August

- Bardhan, Pranab (2011): Awakening Giants: Feet of Clay, Oxford University Press,

- Aggarwal, Aradhana (2020): “Slogans, Policies and a Reality Check”. The Financial Express, August

- Goyal, Garvit (2020): “Vocal for Local: PM Narendra Modi’s big boost to Indian companies”. The Economic Times, May 19.

Brilliant expatriation on the state of Indian economy in post-independence period by a scholar-bureaucrat. The article informs as well as enlightens the reader.