Introduction

The formation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is only the latest step in the gradual shift of the world’s power pole to the Indo-Pacific region. The conventional view is that this process of ‘orientalisation’ (from a Euro-centric perspective) began symbolically either with the dissolution of western colonial empires in the nineteen fifties or perhaps with the economic rise of China from the eighties or even later in the wake of the US-centric financial crisis of 2007/08. However, historians can look further back into the past, when some South Asian and later European states extended their reach, through explorers, warriors and traders, towards the ‘Far East’ and the hitherto mythical ocean which Magellan called ‘Pacific’ in 1521 after reaching it through Cape Horn during his global circumnavigation in the service of the Spanish Crown.

The Indo-Pacific Before European Colonisation

Genetic research has found traces of human migrations from Africa towards the Indian subcontinent and beyond, – when much of now insular South East Asia was still a continent called Sunda – from over 75,000 years ago.[i] The oldest ‘Papuan’ settlements of Melanesia in New Guinea are dated to 50 or 60,000 years ago. Subsequently, genetic evidence of the arrival of populations of probable Indic origin in Australia about 5000 years ago has also emerged.[ii]

From about that same period at least ocean-farers from South Eastern China and Taiwan gradually migrated to Pacific Islands where they are collectively known as Austronesians. There were since undetermined antiquity crisscrossing maritime migrations between Asia and South America as Thor Heyerdahl sought to demonstrate in his 1947 KonTiki expedition from Ecuador to Easter Island. The descendants of those oceanic nomads of diverse origins, who must have mingled on some of the islands where they landed, are called Melanesians, Micronesians and Polynesians. Theories regarding Japan’s Jomon people (believed to have originated on Sundaland) having visited the coast of Peru and influenced the local Valdivia culture[iii] are not proven but have not been convincingly debunked either and certain Chinese annals apparently refer to mariners from the Middle Kingdom having landed on the western coast of North and Middle America during the European Middle Ages.

Chinese annals record Xu Fu’s far-reaching expedition of 219 BCE in search of the elixir of immortality in the eastern seas. Much older contacts between the two sides of the Pacific cannot be ruled out especially when we take into account equally long oceanic voyages proven to have occurred in other directions, such as the crossing of the ‘Chamorros’ from the Philippines to the Marianas in about 1500 BCE and the transfer of the Merinas from Borneo and other ‘Malayan’ islands to Madagascar before the 5th century CE, the to and fro journeys of Indian seamen to the East Coast of Africa and as far away as China, Japan and Korea on the other, and later the arrival of traders from Oman, Yemen and the Gulf states to the Indonesian archipelago, China and the Philippines.

Chinese junks are known to have sailed into the Indian ocean for many centuries, even before the famous expeditions of Admiral Zheng He to South Asia and East Africa in the early decades of the 15th century CE. There is speculation that the Indian sailors ventured eastwards beyond their well identified ports of call in the Malayan archipelago and in the ‘future’ Philippines and landed on some of the South Pacific Islands, where traces of their passage and cultural influence are suspected by certain scholars.

Without drawing definite conclusions, architectural and sculptural similarities between ancient Hindu-Buddhist monuments in Java and Bali on the one hand and more or less contemporaneous landmarks in Mayan, Olmec, Pre-Incan Meso-America are troubling. Books by US Ambassador Miles Poindexter[iv] about ancient Pre-Columbian Peru are among the works that argue in favour of religious and cultural contacts with ancient India. Those theories are however now discarded by historians and archeologists, generally biased in favour of indigenous origins and agnostic about transoceanic connections in antiquity. However, the extensive reach of Indian navigators is attested by the arrival of traders Buddhists ‘missionaries’ on China’s coast at least fifteen centuries ago[v] and by the fact that lands now under the flags of Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, Brunei and the Philippines were ruled for many centuries by Rajas and Sultans who shared at least some cultural and ethnic inheritance from Bharat.[vi]

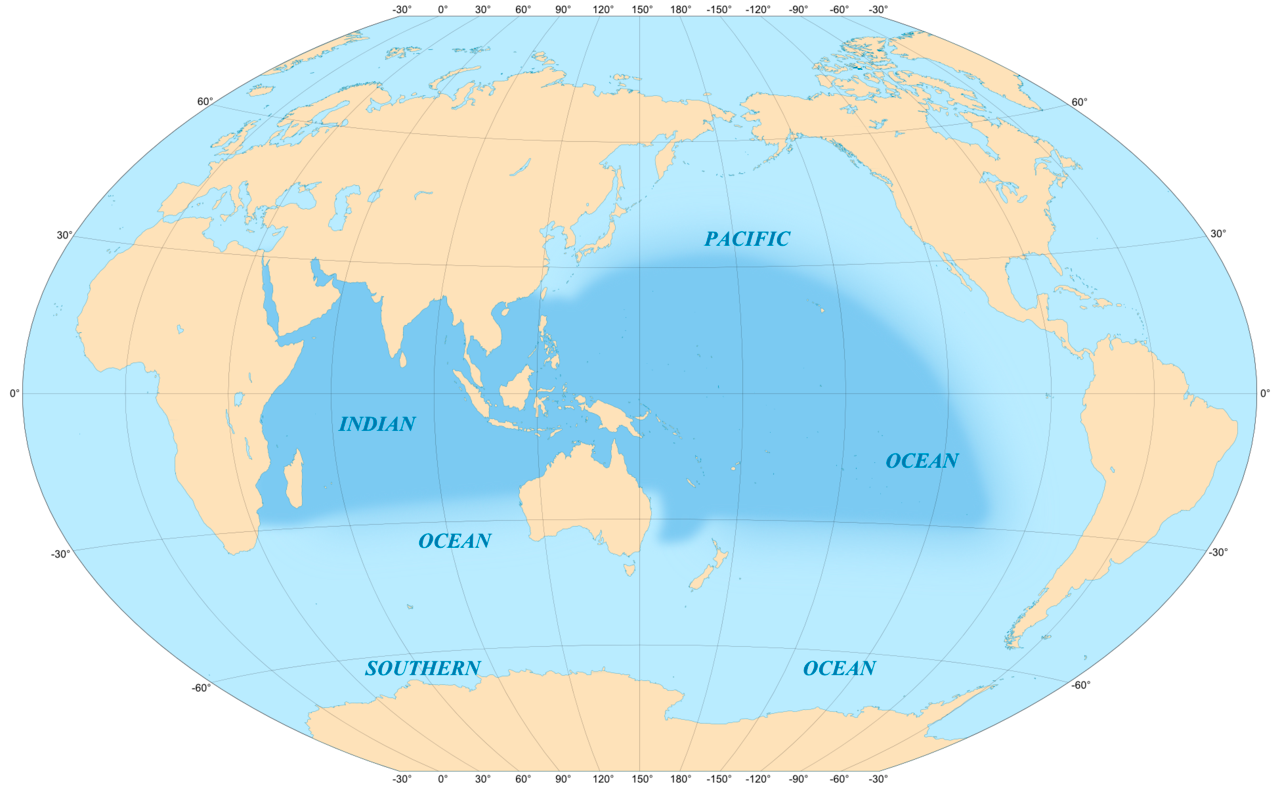

The Pacific hydrosphere which accounts for one-third of the total surface of our planet can indeed be called the liquid hemisphere in comparison to its other half which gathers Eurasia, Africa and the Americas around the narrower Atlantic. Whereas the Indonesian Islands stand as a barrier broken by various straits between the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, to the south of Australia the largest and third largest water surfaces merge seamlessly all the way to Antarctica.

During many centuries for Europeans, the Erythrean Sea, as the ancient Greeks called it according to an Egyptian nomenclature, was an almost mythical marine realm, located between Arabia Felix, Ethiopia (the legendary kingdom of Priester John) and the Indies. That ocean harboured paradisiac islands such as Chrysos (the suvarnadvipa of Sanskrit and Pali literature) and Argyros, rich in gold and silver and Serendip or Taprobane which was often identified with the biblical Garden of Eden, first home of Adam and of the human race.[vii] Further away lay the empires of Cathay and Cipango.[viii]

European Competition and Hegemony

The mix of popular legends, graeco-roman records and accounts of Arab travellers as well as the appetite for spices, precious stones and gold spurred the desire of Atlantic littoral nations to reach those Antipodes by sea as the long and hazardous land routes had been closed by the Ottoman Sultanate’s gradual takeover of the Byzantine empire. In the wake of the maiden westward voyage of Cristoforo Colombo on behalf of the Spanish Crown in 1492 and the earlier landing of Portuguese Bartolomeu Dias at the Cape of Good Hope in Africa in 1488, the two Iberian kingdoms laid rival claims to what was believed to be the Indian continent. To avoid a conflict Pope Alexander VI drew an imaginary line across the Atlantic to divide the respective domains of exploration and conquest. The treaty of Tordesillas signed in 1494 between Portugal and Castille-Aragon gave the western side to the Spanish and the other to the Lusitanians. While the Spanish invaders of Mexico first gained access to the Pacific when Nunez de Balboa sighted it in 1513 from the Panama isthmus, the Portuguese going around Africa followed the Indo-Arab sea routes and set up trade outposts in Nusantara (Indonesia) after taking Malacca in 1511. One year earlier the second ‘Viceroy of India’ and first ‘Admiral of the Indian Sea’, Alfonso de Albuquerque had seized Goa of which he was titled Duke. The Portuguese reached Taiwan that they called Formosa, coastal China (Guangzhou) in 1513 and in 1543, Japan, where they set up a bridgehead in 1571.

In the China Sea the Portuguese met their Iberian neighbours arriving from the other side of the world. Spain colonised the Philippines and planted its flag on a number of Pacific Islands in the course of and after Magellan’s initial periplum. A first treaty was signed between Spain and Portugal in 1529 to delimit their respective claims. From 1580 the two nations were under a single ruler as Philip II inherited the Lusitanian throne but in 1640 Portugal recovered its independence under the dynasty of Braganza at about the time when the two imperial nations began their slow decline, partly as a result of reverses inflicted upon them by envious neighbours, namely the Dutch, the French and the English.

We must however pause for a few paragraphs to consider the extraordinary destiny and fortune of these two rather sparsely populated and resource-poor countries[ix] situated at the southern extremity of Europe and long under African-Muslim dominance. For about a century they exercised almost unchallenged control over most of the ‘new’ non-European world and the Spanish King-Emperor also ruled much of the ‘old’ continent within his vast Austro-Germanic, Flemish and Italian possessions. The takeover of the antipodal hemisphere began about the time when Charles of Habsburg was enthroned Monarch of Spain at sixteen in 1516 and crowned Kaiser of the Holy German Empire in 1519, thereby reviving the vision of a universal Christian empire with Rome, then the focus of the renaissance as the spiritual capital.

Spain and Portugal both pursued the reconquista of the Iberian territory, completed at the end of the 15th century, by attacking the ‘Moors’ in North Africa and then striking the Ottoman Empire from the Arabian Sea. For them it was a resumption of the aborted Crusades. We can understand the first Portuguese and Spanish expeditions to the ‘Indias’ from the West (Colombus) and from the East (Vasco de Gama) as a pincer operation with the combined goals of defeating the Muslims, converting pagans, controlling the spice trade, finding overseas wealth and even discovering the earthly paradise and the fountain of eternal youth.

When Colombus reached what is still known as the West Indies he was convinced to have reached the mythical continent and the name was retained in the Spanish nomenclatures. The western seaboard of the Americas was later eventually reconnoitred and partly settled by the Spanish from Tierra de Fuego to Alaska while the western shores and insular lands of the Pacific from Australia (first sought, named and probably sighted by Queiros and his lieutenant, Torres, in 1605 and 1606) to Korea were explored, mostly by the Lusitanians in the same span of about a hundred years.

The Indian Ocean, between South Africa and the Indonesian archipelago came under the sway of Portugal which pushed out the Turkish and Egyptian Mamluk fleets while establishing diplomatic relations with the Persian, Omanese, Ethiopian, Gujarat and Malabar kingdoms. Contemporaneously, the Pacific Ocean became a Spanish lake whose access was jealously guarded from Mexico, La Plata, Peru and the Philippines and denied to other European states. During the same period the very catholic king of Castille, Aragon, and several other European states claimed supremacy over North America with the exception of the northeastern corner (today’s Quebec and New England) where the French, English and Dutch made early inroads.

Thus, the Indo-Pacific maritime domain was to some extent unified (given the seafaring and military means available at the time) under a single power from the second half of the 16th century to the middle of the 17th century, the period which remains known in Spain as El Siglo de oro: The Golden Century. The Iberian dyarchy was the first transcontinental hegemon, controlling much of the world through the oceans, as Netherlands and England were to do later when they took over the South Atlantic and Indo-Pacific sea lanes. The later part of this article will remind us that this centuries old contest continued until today when it has entered a new phase.

The early 17th century saw the irruption of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the Indo-Pacific also around the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch had gained a foothold in today’s Indonesia by 1603, reached Japan in 1609 and set up trading factories in Surat in 1616 and in Bengal (Chinsura) in 1627. Soon after, other Hollanders arrived from the East, around South America, beginning with Lemaire and Schouten’s exploration of the Pacific during which they laid anchor in New Zealand and other islands in 1616.

The Dutch commercial enterprise was an indirect consequence of the migration of Marrane Jewish financiers and shipping magnates from Inquisition-dominated Portugal to protestant Netherlands, recently freed from Spanish control and still at war with Madrid. That small but wealthy community brought to the Low Countries its knowledge of the hitherto Muslim dominated Indian Ocean trade, its access to the jealously kept secrets of Portuguese overseas portulans (navigator maps) and its far-flung banking network. In the same period, Hispanic maritime preponderance was decisively weakened by the allied English and Dutch when most of the ‘invincible” Spanish Armada was blown off by a storm and largely destroyed near the Irish coast in 1588. Philip II’s attempt to crush the privateers who regularly plundered Spain’s overseas ports and convoys had dismally failed.

By 1650, the Netherlands began to take over Lisbon’s possessions in India, Ceylon and Indonesia (between 1656 and 1661) while simultaneously expelling the Spanish from Taiwan, establishing themselves in eastern North and South America and encroaching on the Spanish Caribbean. The British closely followed them in India and the Malayan archipelago. French ships also made their appearance at that time and King Louis XIV’s reign saw the acquisition of the first French enclaves (Pondicherry and others) in coastal India and the opening of diplomatic relations with Siam (now Thailand).

Holland’s supremacy, battered by French invasions and financial bankruptcy was relatively short lived and the United Kingdom, instead of the United Provinces became the main challenger of the sprawling Spanish and Portuguese dominions, even before the 1688 revolution which brought to the throne in Westminster, the Dutch Prince Wilem of Orange accompanied by a large number of traders and bankers from the Low Countries.[x] However, thanks in part to their alliance with London, the Low Countries retained their hold over most of the Malayan islands.

The capitalistic extractive system inaugurated by the giant Dutch East India Company and inherited by its British ‘clone’ was to gradually replace the old Iberian Catholic state-controlled colonisation. The new shareholder-operated type of organisation would soon be adopted by other empire building states, primarily France, Denmark, Russia, the Austro-German Empire and applied to ever larger annexed territories outside Europe in the course of the following two centuries.

We must however not lose sight of the fact that the matrix of world unification (‘the empire on which the Sun never set’) which Britain saw itself close to achieving in the late 19th century under Queen Victoria’s reign had been projected by Charles V (Carolus Quintus, often described in his day as ‘Imago Imperatoris’) and his son Philip II who saw themselves as the paladins and protectors of the Roman Catholic Church and Faith. They were tasked by the Papacy with the mandate to extend its sway ‘urbi et orbi’ with the backing of the Italian banking houses and christian monastic orders, particularly the Jesuits, in that era of triumphant counter-reformation. It is under the rule of those Hasburg monarchs coincidentally that the silver Thaler or Dollar became the currency of their world-spanning realm.

Britain inherited much from the Spanish-Portuguese imperial experience: the slave and spice trade, sea route secrets, bridgeheads, military and administrative methods but also hard assets—through the plunder of the galleons and commercial harbours of Asia and the Americas—and even the name of the currency later adopted by the future United States as its national denomination.[xi] A well-known but relatively rare example of legal territorial acquisition was the gift of the settlement of Bombay to England by the Portuguese crown as part of the dowry of Princess Catarina de Braganza, the young bride of British King Charles II in 1662.

The Second Colonial Period

If we glance at the history that unfolded from 1700, when the War of Spanish Succession accelerated the decline of Spain and the rise of Britain (in whose orbit Portugal henceforth gravitated), we need to recall that it took two more centuries for Madrid’s rule over much of the New World and the Pacific to end. In 1898, almost a hundred years after losing Latin America, Spain was forced to surrender the Philippines to the USA which, in the course of its continuing westward expansion annexed Hawaii in the same year.[xii]

About a decade earlier Madrid had ceded many of the 6000 Pacific islands it occupied or claimed to Bismarck’s Germany, the new empire builder. Small Portugal had declined faster, and early in the 19th century lost all but a few fragments of its Asian possessions to the English and Dutch. The other winners in the 19th century were the French who retained several islands in the Indian Ocean, eventually annexed Djibouti and Comoros in 1883 and 1886, Madagascar in 1895 and conquered much of the Indochinese peninsula while taking over several Pacific archipelagos which they have kept until today. France owns the largest maritime exclusive economic zone in the Indo-Pacific after the USA and Australia.

The alliance between the two realms of the House of Bourbon had empowered French navigators such as Bougainville and La Pérouse to explore the Pacific before the Revolution of 1789 in the period when Cook was doing the same for the United Kingdom. In the following century, France used that capital of information to take over huge swathes of the ocean. The Society (Tahiti) and Marquesas archipelagos became part of the French empire in the 1840s and New Caledonia was annexed in 1852, the very year when Commodore Perry, commander of the US ‘East India Squadron’ landed in Japan and compelled the Empire of the Rising Sun to open its borders to foreign trade. By then Britain had acquired Hong Kong and won increasing influence in the decadent Qing Chinese Empire.

Russia, which had become an Asian power by the close of the 17th century and dispatched the Kruzenstern naval expedition around the world in 1803, opened an ice-free port on the Pacific on land taken from China at Vladivostok in 1860. However, the sale of Alaska to the USA in 1867 showed the limits of the Tzarist Empire’s means and ambition. The defeat of the Russian fleet at the hands of Japan in 1905 in Manchuria was one of the disastrous events that led to the collapse of the imperial autocracy in 1917. It was only during the second world war that the USSR again projected some naval power in the Pacific theatre.

The 1914-18 war ended in Germany’s loss of all its recently acquired overseas dependencies and ushered in the interlude of Japan’s occupation of a vast (Asian-Pacific) ‘sphere of co-prosperity’. With the total defeat of the Empire of the Rising Sun, the first Asian nation to vie for maritime hegemony in the hemisphere, the second world war brought it under the triumphant USA’s control or influence, institutionalised in 1954 by SEATO, the ‘Asia-Pacific NATO’ in which significantly Pakistan was included.

The defeat of the Kuo Ming Tang regime resulting in the foundation of the Maoist People’s Republic of China in 1949 was the first blow to Anglo-Saxon led Euro-American supremacy at the time when the Soviet Union got the atom bomb. The American defeat in and exodus from Vietnam some two decades later and the dissolution of SEATO in 1977 confirmed that power was changing hands. It would however take more decades for the “Middle Kingdom’ to set its sight on maritime expansion for regaining its ancient preeminence in the China Sea and staking claims in the western Pacific.

Certain scholars[xiii] describe Beijing’s push towards the ocean and its rush to deploy a blue water navy as a strategy inspired by the theories of American military scholars A. T Mahan and N. Spykman about the criticality of maritime power. China claims the oceanic space within the ‘nine dash line’ first drawn by the KMT nationalist government of Chang Kai Shek in 1947 and, in order to gain control, is striving to break in stages through the three island chains that US Secretary of State J F Dulles described in 1951 at the height of the Cold War as the successive barriers the US would utilise to contain the People’s Republic. The closest to China’s mainland stretches from the Kurils, through Japan, the Philippines, Ryukyu and Taiwan down to Borneo. The second lies between the Bonin archipelago, Guam in the Marianas and New Guinea. The third and outermost chain symbolically connects the Aleutian Islands near Alaska to Hawaii and Australia. The three chains or barriers are all under the direct or indirect sway of the Americans, buttressed by their allies, including South Korea in the North, Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia in the South and once again Vietnam which has conflictual relations with China.

In order to break out of those ‘containment belts’ from where the USA and its allies could launch attacks on China by air and sea and cut off the marine supply lines, the PRC has fortified several islets in the South China sea while aggressively pressing its ancient but shaky claims on contested archipelagos: the Paracel, Spratley and Senkaku islands. Beijing regards that maritime territory as its own ‘Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean’, vital to its security and has built major naval surface and submarine infrastructure in the island of Hainan in order to protect it. It is only the second time that an Asian power, after Japan seeks to acquire dominance in the Pacific in the last five hundred years, since the fateful arrival of the first Portuguese and Spanish Caravels into the ‘Mares do India’.

Conclusion

The Indo-Pacific was under European hegemony from about 1510 to 1900 and fell increasingly under US control in the 20th century. The second world war turned it into a virtual lake of the United States and of their French, British-Australian and other allies which conducted nuclear tests in their respective possessions. Only Russia could hitherto challenge the western condominium in the North West Pacific while India all along has exercised some control over the Indian Ocean, hedged in by the US bases in Diego Garcia and in the Persian Gulf.

In the last twenty years China has raised its strategic stature at sea and is contesting the long-standing ‘Euro-American’ hegemons. The US-led ‘Five Eyes’ strategy is intended to maintain supremacy by sharing some of it, mainly with Japan and Australia in the Pacific and with India and Indonesia in the Indian Ocean. To retain its regional maritime predominance, New Delhi is working primarily with France the other ‘Big’ maritime power in the IOR and with Russia, the traditional military partner while engaging in limited and case-specific cooperation with the three other Quad associates and with ASEAN members Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam.

India’s strategy for protecting its interest and influence in the Indian Ocean through the recently set up Information Management and Analysis Centre (IMAC) involves weaving close partnerships with the littoral and island nations of Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles, Madagascar, Oman, Bangladesh and Myanmar and relying on a monitoring and surveillance grid (Information Fusion Centre for the Indian Ocean region or IFC-IOR) connecting seven offshore hubs stretching from the Seychelles and Duqm port in Oman to the naval station at Sabang in western Sumatra, Indonesia[xiv] close to the Malacca Strait. The ongoing power shift from the western to the eastern hemisphere probably spells the gradual eclipse of Euro-American supremacy in the seas that surround the Asian continent.

Author Brief Bio: Mr. Côme Carpentier de Gourdon is currently a consultant with India Foundation and is also the Convener of the Editorial Board of the WORLD AFFAIRS JOURNAL. He is an associate of the International Institute for Social and Economic Studies (IISES), Vienna, Austria. Côme Carpentier is an author of various books and several articles, essays and papers.

[i] The continent of Sunda was gradually submerged by the rise in sea levels from about 19000 to 5000 years ago when only the higher lands that form Indonesia and peninsular Malaysia remained above the water. Bellwood, P (2007) Prehistory of the Indo-Malayan Archipelago, Rosen (Ed). ANU Press.

[ii] Some genomic findings led ethno-geneticists to posit the arrival of settlers from India in Australia around 5 or 4 000 years before the present. A more definitive and recent study has concluded that Aborigines were in Australia at least 50 000 years ago but that females of ‘Indian origin’ (closely related to certain populations in Tamil South India) may have mingled with the earlier settlers a few thousand years back. Many mysteries remain about the routes and dates of migrations across the Indo-Pacific. Cf https://www.vijayvaani.com/ArticleDisplay.aspx?aid=5599

[iii] Archeologists inferred this maritime connection from similarities between the styles of pottery found in Japan from the Jomon era which lasted from about 14000 until about 300 BCE and those of the Valdivia coastal culture of Peru (3000-2700 BCE).

[iv] Poindexter, Miles (1930), The Ayar-Incas (vol I) and Asiatic Origins (vol II), New York.

[v] Regarding ancient trade routes across Indian Ocean and South China Sea cf: https://www.booksfact.com/history/ancient-maritime-route-india-egypt-africa-china-350-

bc.html#:~:text=Ancient%20Maritime%20Route%20Between%20India%2C%20Egypt%2C%20Africa%2C%20China,into%20Europe%20over%20sea%20as%20well%20as%20land.

[vi] The western direction in many of the local Malayan languages is still known as Barat and so it is in Madagascar’s national medium because of the South Asian roots of many of the malagasy peoples (even though India lies to the east of Africa).

[vii] Among ancient sources cf Hereford Mappa Mundi which situates the Eden of Genesis somewhere in the Indian Ocean. It was later identified either with Ceylon (Serendip), Java or Sumatra (menoftheweb.net/the-earthly-paradise-part-1; retrieved on 3/12/2020).

[viii] Cathay (Kitai, the home of Khitans) was usually regarded as distinct from China. Marco Polo calls North China Cathay and South China Mangi. Cipango was the name given to Japan by Marco Polo. Columbus believed he had reached it in the Caribbean and claimed it for Spain. It was thought to be the closest part of India on the westward route.

[ix] In 1550 the population of Portugal was little above 3 million. Spain had 8 million inhabitants then.

[x] In 1655 the Amsterdam-based Sepharad Cabbalist and Talmudist Menasseh ben Israel won a historic concession from the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell to allow Jews to settle in England from where they had been expelled in 1290. That agreement, opposed by many in the English Parliament, heralded the rise of British overseas expansion and the corresponding loss of Dutch preponderance illustrated by the ‘glorious revolution’ against the Stuarts which brought to the throne William of Orange-Nassau.

[xi] One fourth of the territory of the United States was gradually taken from Spain and another fourth was acquired from France through the Louisiana purchase of 1803.

[xii] US scholars have noted that the annexation of the kingdom of Hawaii through the machinations of American planters settled in the islands was not in conformity with the US constitution and never went through the due constitutional process.

[xiii] Michael Gunter Chinese Naval Strategy – The influence of Admiral Mahan’s Theories of Sea Power, World Affairs, vol. 24, no. 3, Autumn 2020 (pp.54-73).

[xiv] Baruah Darshana M, Carnegie Endowment’s Report on the Indo-Pacific, June 30, 2020. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Baruah_UnderstandingIndia_final1.pdf

Sir,

Brilliant article. But I differ on one point. Assertion by learned author that “Genetic research has found traces of human migrations from Africa towards the Indian subcontinent and beyond” is not correct. In fact from tools excavated from Athiram Bakkam near Kanchipuram in Tamilnadu (India) have confirmed that there was some form of Human or Homo Sapiens/Homo Erectus life in India during the period about 1.8 million years ago. Stone axes were found there some of which are displayed in a museum at Vellore Fort which are found to be about 1.8 million years old.Latest genetic research (https://www.academia.edu/44630162/Out_of_India_By_Land_or_By_Sea_A_Paradigm_Shift_in_Ancient_Migration_Theories?email_work_card=title ) have proved that the theory of human migration from Africa towards Indian subcontinent is faulty. In fact this was reverse migration.Humans had earlier migrated to Africa and beyond by land route via Lemuria which connected southern India to Africa Continent. This land mass of Lemuria was submerged later.

Moreover, at Jwalapuri near Chennai man made stone tools are found that date back to at least 74000 years when magma from Mt.Tobu volcano dropped there.Admittedly, Mt Tobu volcano in Indonesia had erupted 74000 ago and its magma had reached upto Iceland. Its layers were found at Jwalapuri where man made stone tools were found below this layer of magma as well as above magma layer. This proves that human life existed in Indian subcontinent much earlier that 74000 years. Then there are more than one lac years old cave paintings at Bhimbetka in Jabalpur of Madhya Pradesh in India.These cave paintings too are the oldest cave painting anywhere in the world.This again proves existence of human life in Indian subcontinent much earlier than one lac years.

With regards,

Anil Gupta, Meerut, India