Introduction

The nature of international relations has been constantly changing over decades and centuries, as the nature of threats to humankind’s continued survival has been evolving. If the transition from the 19th to the 20th century saw the emergence and the re-emergence of the conflicts over physical boundaries between states comprising the international system, then the transition from the 20th to the 21st century saw the emergence of the non-state actor as a potent threat in international relations. The 21st century, as juxtaposed to the previous centuries, is undergoing a host of changes ranging from cyber warfare to increase in artificial intelligence to biological warfare to the emergence of a global scale pandemic—all of which seriously threaten the continued existence of humankind. What has also become identified as a potent threat in the 21st century is climate change. While climate change per se did not emerge overnight and is an outcome of centuries of pollution, the problem has reached alarming levels given the massive number of changes taking place owing to climate change. What is more worrisome is the fact that while climate change has been recognised as a threat to humankind, states of the international system still undertake an outdated, almost territorial approach on the issue, refusing to take responsibility for change and trying to extract maximum benefits out of the existing international system for the fulfilment of their own narrow selfish interests.

The challenge becomes a type of protracted conflict as developed countries of the rich North constantly seek to evade their historic responsibility for polluting the world for decades, while trying to put emission caps on the developing world. For the developing world this becomes challenging as levels of development are directly proportional with carbon emissions. A halt to emissions also means a halt to economic development which in turn will jeopardise the lives of billions living in the developing world.

In the recent past India and China have often joined hands at climate change negotiations to remind the developed rich North of their historic responsibility for climate change and to negotiate caps on emissions in accordance with countries’ responsibilities for global warming. However, what has also been witnessed with regards to China is a peculiarity in this context. While China is a developing country and does not have the same historic responsibility as the developed world, China currently is also the biggest emitter of fossil fuel carbon dioxide emissions, and it accounted for more than 27 percent of total global emissions in 2020 (BBC, 2021). China emits more greenhouse gases than the entire developed world, with the US being the second largest emitter at 11 percent while India was third with 6.6 percent of the emissions (Ibid.).

China’s emissions have more than tripled in the past three decades. In fact, while Xi Jinping previously stated that China would strictly control coal fired generation projects, China has only been increasing construction of coal-fired plants (Volvovicci, Brunstrom and Nichols, 2021). State owned Bank of China has been constantly financing overseas coal projects with its funding reaching USD 35 billion since 2015 (Stanway, 2021). In September this year, Xi Jinping stated that China will not build new coal fired projects abroad. However, facts on the ground state something else, as the energy crisis that China finds itself amidst will push China to consume more coal to ensure continued electricity supply. Power cuts of various magnitudes have been witnessed in at least 20 provinces across China since mid-August this year. Shortage of coal supplies, tougher government mandates to reduce emissions and a greater demand from manufacturers have all contributed to the current situation (Lee, 2021). The energy crisis has halted production in various factories across China, which is going to have an impact on an already slowing economy. Therefore, China will have to balance its act between clean energy and declining growth rates. In this context, it becomes pertinent to look at some of the pledges Xi has made in the past regarding usage of clean energy.

Xi’s pledges regarding combating climate change

Even though Xi Jinping did not attend the COP 26 this year, he had announced last year that China’s carbon emissions will begin to decline by 2030 and that China will reach carbon neutrality by 2060 (Ibid.). For the purpose, China introduced a dual control policy which requires Chinese provinces to limit energy use and to cut energy intensity, which is defined as the amount of energy used per unit of gross domestic product (GDP). The dual control system was first set in China’s 11th Five Year Plan (2006-10). However, it has gained in significance post Xi assuming the reins of power and committing to China peaking carbon emissions by 2030 and to becoming carbon neutral by 2060 (CGTN, 2021). The plan was to set a five-year target of energy consumption and energy intensity for different provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in an effort to reasonably manage the indicators of total energy consumption and energy intensity (Ibid.).

During the 2015-2020 period, China had a national target for a reduction in energy intensity of 15 percent. The latest five-year plan adopted in March this year targeted a further 13.5 percent cut by 2025 (Gao, 2021). Because of these plans, phased goals were set in place, and it was assumed that by 2025 the dual control system would be more complete with better allocation of energy resources and better energy utilisation. In this context, it becomes pertinent to take a closer look at how Chinese provinces have performed with regard to the dual control system.

In mid-August this year, China’s economic planning agency announced that 20 provinces had failed to meet their targets in the first half of 2021 (Lee, 2021). In late 2020, several provinces were reported to be struggling to meet their targets, as difficulties got exacerbated by COVID19. Some provinces even took drastic measures of cutting off power supplies to comply with the targets. This led to a realisation that an examination of the efficacy of those targets are needed. In the meantime, China’s carbon emissions went up 15 percent year in year in the first quarter of 2021 (Xie, 2021).

To deal with the possibilities of further power shortages, China is pushing miners to ramp up coal production and is increasing imports so that power stations can rebuild stockpiles before the winter heating season begins (Singh and Xu, 2021). China’s imports of coal jumped 76 percent in September this year from a year ago (National Development and Reform Commission, 2021). This is despite the pressures and the announcements made to meet targets for reducing carbon emissions. In addition to the impacts of the dual control policy, China’s thermal coal supplies have also been impacted by the recent floods in Shanxi province which is a key coal producing province (Reuters, 2021). China is already the world’s largest coal consumer and of late it has been grappling with a growing energy crisis brought on by shortages caused by natural as well as humanmade causes. The result has been shortages and record high prices.

A closer observation at China’s emissions reveals that while per person China’s emissions are about half of those of the US, its 1.4 billion population and its breakneck speed economic growth, reliant heavily upon coal energy; have pushed it way ahead of other countries in terms of overall emissions. It was first in 2006 that China became the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide in 2006 and is now responsible for more than a quarter of the world’s overall greenhouse gas emissions (Brown, 2021). Instead of shutting down coalfired power stations, China is actually building new ones at more than 60 locations across the country with many sites having more than one plant (Ibid.). In this context, it becomes pertinent to understand China’s coal reliance. The following graph shows how coal consumption has grown over the years in China.

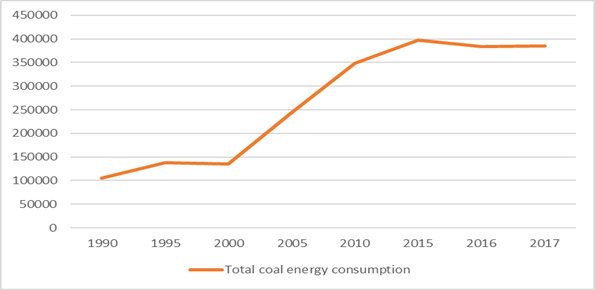

Graph 1: China’s Total Coal Energy Consumption

Unit: 10,000 tons

Source: National Bureau of Statistics, China Statistical Books 1991-2018, People’s Republic of China

Beginning from the 1990s onwards, China’s reliance on coal to spur economic development began. Its coal consumption has only grown over the years as seen in graph 1, in tandem with its economic growth rates. China’s coal consumption grew from 1.36 billion tonnes per year in the year 2000 to 4.24 billion tonnes per year in 2013, which represents an annual growth rate of 12 per cent (Qi and Lu, 2016). By 2015 itself, China accounted for 50 per cent of the global demand for coal (Ibid.).

In fact, in 2020 during the pandemic, China was the only major industrial power whose carbon emissions rose, as the central government relaxed a traffic light system designed to reduce overcapacity among coal burning state owned enterprises with a plethora of coal power projects given the go ahead (Cash, 2021). Because of China’s coal addiction, it faces the difficulties of energies transition. What also remains a big hurdle is the existence of big energy and manufacturing lobbies which laud the central government’s placing of higher emission caps while these big polluting lobbies continue their pollution spree.

In 2019, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), issued a new policy for reorganising the state-owned enterprises which dominate coal generation. The first of such an announcement was made in November 2019, followed by a more detailed statement in May 20 (Huidian Dianping, 2019). The details listed were about reorganisation efforts in the Northwest region, where coal overcapacity and financial losses are maximum. The SASAC had also stated that the plans would likely be expanded to other coal intensive parts of the country. The plan called for stricter controls of coal capacity, elimination of outdated capacity, reductions in coal-fired capacity for the Northwestern region and mergers of SOEs to form a single coal generation SOE for each of the provinces in the region (Dupuy, 2020). While the SASAC’s plans are laudable, it was argued that the plans for consolidation of ownership threaten the wholesale electricity markets that the National Development and Reform Commission was fostering and that SASAC’s planned mergers would dampen competition (Ibid).

Ma Jun, the director of the Institute of Planning and Environmental Affairs, which tracks environmental and climate records of big corporations stated that achieving climate targets while fulfilling other demanding targets needs a good transitioning strategy and so far, there are still major gaps (Stanway, 2021). China has a per capita level of carbon dioxide emissions that is far above that of countries with a similar level of per capita GDP (AFP, 2021). In fact, in 2019, China’s per capita emissions reached 10.1 tons, almost tripling over the las two decades. This was just slightly below average levels across the OECD bloc, which stood at 10.5 tons per capita in 2019. China’s per capita emissions even though significantly lower than the U.S. at 17.6 tons per capita still is significantly high. According to Larsen, Pitt, Grant and Houser (2021), China’s per capita emissions exceeded the OECD average in 2020, as China’s net greenhouse gas emissions grew about 1.7 percent while emissions from almost all the other countries declined sharply during the pandemic (Larsen, Pitt, Grant and Houser, 2021).

China’s carbon dioxide emissions rose by 9 percent in the first quarter of 2021 as compared to pre-pandemic levels (Reuters, 2021). This rise was driven by a carbon intensive economic recovery and massive hikes in outputs of steel and cement, which in turn rose as part of the attempts to reinvigorate and jump start the economy as part of post pandemic recoveries. Output from the industry and construction sector increased by 2.8 percent, steel by 7 percent and cement and coal mining by 2.5 percent and 1.4 percent respectively last year (Bloomberg, 2021). This raises questions whether the country can meet its 2060 carbon neutrality pledge. As such, China’s energy trajectory since COP 21 contradicts the goals. Even though the new five-year plan of 2021-2025 shows a lot of intent regarding carbon neutrality, numbers give out a completely different story. In this context it becomes pertinent to analyse China’s COP 21 goals.

China’s Between COP21 and COP26: Xi’s Pledges

In 2015, at the COP 21, Xi, while urging developed countries to fulfil their commitments to providing funds to developing countries to tackle climate change, pledged that China has plans to achieve the peaking of carbon dioxide emissions around 2030 (Liu, 2015). He had also pledged that China would become carbon neutral before 2060. In 2021, even though Xi did not attend the COP26, China submitted its nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to fight climate change, which were published on the website of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which showed that China aims to see its carbon dioxide emissions peak before 2030 and it aims to become carbon neutral before 2060. This was in tandem with the pledges Xi had made earlier. The point to remember is that the NDCs are non-binding national climate change plans that must be submitted regularly to the United Nations as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement and countries may enhance their ambitions if they are able to do so.

This year, ahead of the COP 26, China enhanced its ambitions, as it committed to raising the share of non-fossil fuels in its primary energy consumption to 25 percent by 2030, which is higher than its previous pledge of 20 percent. China also pledged to increasing its wind and solar power capacity to more than 1,200 gigawatts. China is already leading the world in renewable energy production figures, and it is the world’s largest producer of solar and wind energy (OECD, 2021). It also is the largest domestic and outbound investor in renewable energy (Jaeger, Joffe, Song, 2017). In 2016 itself, a year after COP 21, four of the world’s five biggest renewable energy deals were made by Chinese companies (Slezak, 2017). By 2017, China owned five of the world’s six largest solar module manufacturing companies and the world’s largest turbine manufacturer (Mooney, 2017). In fact, solar energy is slated to become the largest primary source of energy by 2035. China’s wind and solar capacity is to rise to above 1,200 GW in 2030 from 530 GW in 2020 (Pillai, 2021).

However, what is also a factor to consider in China’s futures in the realm of carbon neutrality is that urbanisation currently stands at 65 percent, and this will go up to 78 percent in 2050 (Ibid). Population and economic development will continue to increase as well, implying a growth in electricity consumption. Economic growth remains a top priority, as stated at the annual ‘two sessions’ in March (Liu, Liu and You, 2021). While China has made strides in renewable energy, fact remains that it is not adequately developed to meet the needs of the entire country. Su Wei, the deputy general of the National Development and Reform Commission stated in April this year that China’s energy structure is dominated by coal power, and that as compared to wind and solar power which are “intermittent and unstable” coal is a stable source of power. He also said that while coal is readily available, renewable energy needs to develop further in China. He added that because of this, for a period of time, China will need to use coal power (Cheng, 2021). This is in complete contrast to Xi’s statements of April this year when he had said that the country will reduce coal usage beginning in 2026 (Ibid.)

In addition to Su’s statement being in complete juxtaposition to what Xi had said in April regarding reducing dependence on coal, point also to note is that China, as stated previously is grappling with its worst electricity shortages in years and has asked miners to increase coal production to supply major power plants! China relies on coal-fired power generation, which is a huge contributor to carbon emissions! Also, the complete absence of Xi Jinping on COP26 also brings forth several questions on China’s seriousness regarding dealing with issues of climate change. Xi delivered a written statement to the opening session of the COP26, which however, did not offer any new climate pledges than what Xi had already made in the past.

Even though China’s 14th five-year plan (2021-26) has outlined an 18 percent reduction target for carbon dioxide intensity and a 13.5 percent reduction target for energy intensity from 2021 to 2025, and has introduced the idea of an emissions cap, it has not really gone so far as to set one (Liu, Liu and You, 2021). However, as displayed by the power crunch this year, which prompted China to redirect support to polluting fossil fuels, China faces an immense difficulty of balancing long-term climate goals with short term energy security. The reason why China did not make any new commitments at the COP 26 is the prevailing domestic uncertainties, because of which China has been hesitant to embrace stronger near-term targets.

Conclusion

China’s strides in renewable energy undoubtedly are laudable and in fact make it in a position to steer discussions on climate change and how to address the challenges. Because of these strides, China felt it was in a place to demonstrate global leadership, which is why after joining the Paris Agreement, China made laudable pledges to combat climate change including plans to reduce carbon dependence. The reinvigorated emphasis on the dual control policy was a step to combat coal usage in China. However, as stated previously, 20 provinces had failed to meet their targets as part of the dual control policy! Also, because of the historical dependence China has on coal, the introduction of sudden controls on coal usage led to a shortage of electricity in the country, which in turn led policymakers to revert to usage of fossil fuels. Additionally, the floods in coal producing provinces like Shanxi dealt a blow to electricity production, which in turn spurred the power outages across the country.

China’s dependence and addiction to coal is displayed by the fact that China delivered 60 train loads of coal to Henan province per day in July when the province reported urgent shortages of fuel to generate electricity, after major transport routes were blocked by an unprecedented deluge (Global Times, 2021). China’s plans thus seem to be in complete contradiction with the pledges Xi had made. Also, as reflected by the failure of 20 provinces to meet coal reduction targets, there is a dangerous lack of urgency in the country. Because of the back and forth between announced policies and prevailing ground realities Chinese attempts to assert its role in the world as a leader is clearly not showing up. Achieving a material and socio-economic transformation that supports the move away from coal needs major changes in governance, policies, planning, investment and organisations practices at various levels. The Chinese political economy is dominated by vested interests and complicated by perverse incentives for unsustainable production.

SOEs in energy intensive industries along with several officials with vested interests have zero or limited interest in curbing emissions or adhering to limitations on coal usage. Central officials often acquiesce or fail to rein them in (Green, 2020). On the contrary there have been drastic increases in coal fired power station development in the last few years (Myllyverta, Zhang and Shen, 2020). Research by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air shows how hundreds of billions of dollars in the post COVID-19 stimulus being earmarked for energy intensive industrial projects. These exceed the planned spending on low carbon energy threefold!

Facts such as these call for caution regarding China’s pledges on climate change; particularly its 2060 carbon neutral target. Between now and 2060 a lot can happen and from the trends it is visible that the government’s medium-term targets give it space to increase emissions until 2030! China is actually culpable for greater levels of pollution and global warming, and Xi’s pledges are only a cover for about another decade of fossil fuel based industrial expansion!

Author Brief Bio: Dr. Sriparna Pathak is an Associate Professor at the School of International Affairs, O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India. She is also the Director of the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies at the School.

References

- AFP (2021). China’s Climate Pledges and The Coal-Driven Economy. May 25. URL: https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/blog/chinas-climate-pledges-and-coal-driven-economy Accessed on November 5, 2021.

- BBC (2021). Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined. May 7. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57018837 Accessed on December 1, 2021.

- Brown, David (2021). Why China’s climate policy matters to us all. BBC News. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-57483492 Accessed on December 3, 2021.

- Cash, Chris (2021), China’s coal addiction is an obstacle to real progress on climate change. City. A.M. November 5. URL: https://www.cityam.com/china-coal-climate-change/ Accessed on December 6, 2021.

- CGTN (2021). China says to firmly control energy-hungry and high-emission projects. September 16. URL: https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-09-16/China-says-to-firmly-control-energy-hungry-and-high-emission-projects-13BHlfbRCes/index.html Accessed on December 4, 2021.

- Cheng, Evelyn (2021). China has ‘no other choice’ but to rely on coal power for now, official says. CNBC. April 29. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/climate-china-has-no-other-choice-but-to-rely-on-coal-power-for-now.html Accessed on December 4, 2021.

- Dupuy, Max (2020). China’s Watchdog for State-Owned Enterprises Grapples With Coal-Fired Generation. The Regulatory Assistance Project. June 8. URL: https://www.raponline.org/blog/chinas-watchdog-for-state-owned-enterprises-grapples-with-coal-fired-generation/ Accessed on December 9, 2021.

- Gao, Baiyu (2021). Without a carbon cap, you can’t provide strong support for a carbon peak. China Dialogue. March 15. URL: https://chinadialogue.net/en/energy/can-controlling-energy-use-drive-chinas-green-transition-during-the-next-five-years/ Accessed on December 8, 2021.

- Global Times (2021). Coal rushed by train to flood-ravaged Henan Province to ensure electricity supply. July 25. URL: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202107/1229540.shtml Accessed on December 8, 2021.

- Green, Fergus (2020). Xi Jinping’s pledge: Will China be carbon neutral by 2060? East Asia Review. October 26. URL: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/10/26/xi-jinpings-pledge-will-china-be-carbon-neutral-by-2060/ Accessed on December 8, 2021.

- Hindustan Times (2021). China’s emissions grew 1.7% in 2020, only major economy to see increase in pandemic year: Report. May 5. URL: https://www.hindustantimes.com/world-news/chinas-emissions-grew-1-7-in-2020-only-major-economy-to-see-increase-in-pandemic-year-report-101614935312967.html Accessed on December 2, 2021.

- Huidian, Dianping (2019), Full text of the state-owned assets project (pilot plan for the regional integration of coal and power resources of central enterprises) (Zhòng bàng! Guózī àn fābù (zhōngyāng qǐyè méi diàn zīyuán qūyù zhěnghé shìdiǎn fāng’àn) quánwén) (重磅!国资案发布(中央企业煤电资源区域整合试点方案)全文) November 30. URL: http://www.tanjiaoyi.com/article-29645-1.html Accessed on December 7, 2021.

- Joel Jaeger, Paul Joffe, and Ranping Song (2017). China Is Leaving the U.S. Behind on Clean Energy Investment. World Resources Institute. January 6. URL: http://www.wri.org/ blog/2017/01/china-leaving-us-behind-clean-energy-investment Accessed on December 3, 2021.

- Larsen, Kate; Pitt, Hannah; Grant, Mikhail and Houser Trevor (2021). China’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Exceeded the Developed World for the First Time in 2019. Rhodium Group. May 6. URL: https://rhg.com/research/chinas-emissions-surpass-developed-countries/ Accessed on December 12, 2021.

- Lee, Yen Nee (2021). Faced with a power crisis, China may have ‘little choice’ but to ramp up coal consumption. October 17. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/10/18/power-crunch-china-has-little-choice-but-increase-coal-use-analysts-say.html Accessed on December 1, 2021.

- Liu, Hongqiao; Liu, Jianqing and You, Xiaoying (2021). Q&A: What does China’s 14th ‘five year plan’ mean for climate change? Carbon Brief. March 12. URL: https://www.carbonbrief.org/qa-what-does-chinas-14th-five-year-plan-mean-for-climate-change Accessed on December 8, 2021.

- Liu, Xin (2015). Xi pledges emission peak around 2030. Global Times. May 5. URL: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/955829.shtml Accessed on December 4, 2021.

- Mooney, Chris (2017). Trump aims deep cuts at energy agency that helped make solar power affordable. Washington Post, March 31. URL: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/ energy-environment/wp/2017/03/31/its-our-central-hub-for-clean-energy-sciencetrump-wants-to-cut-it-massively/?utm_term=.868a2e1c3b65 Accessed on December 8, 2021.

- Myllivirta, Lauri; Zhang, Shuwei and Shen Xinyi (2020). Analysis: Will China build hundreds of new coal plants in the 2020s? Carbon Brief. March 24. URL: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-will-china-build-hundreds-of-new-coal-plants-in-the-2020s Accessed on December 5, 2021.

- National Development and Reform Commission (2021). Notice on “Measurement of Completion of Energy Consumption and Dual Control Targets in Various Provinces in the First Half of 2021” (Guānyú yìnfā “2021 nián shàng bànnián gè dìqū néng hào shuāng kòng mùbiāo wánchéng qíngkuàng qíngyǔ biǎo” de tōngzhī) (关于印发《2021年上半年各地区能耗双控目标完成情况晴雨表》的通知)

- OECD (2021). Renewable Energy. URL: https://data.oecd.org/energy/renewable-energy.htm Accessed on December 2, 2021

- Pillai, Reji (2021). China’s Renewable Energy Goals. Seminar ‘China’s Goals for 2035: Prospects and Challenges”, on December 8, 2021. New Delhi, Ministry of External Affairs, India.

- Reuters (2021). China CO2 emissions 9% higher than pre-pandemic levels in Q1 -research. May 20. URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/china-co2-emissions-9-higher-than-pre-pandemic-levels-q1-research-2021-05-20/ Accessed on December 4, 2021.

- Singh, Shivani and Xu, Muyu (2021) China coal futures slump as gov’t signals intervention to ease power crisis. Reuters. October 21. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-coal-futures-dive-further-signs-govt-intervention-2021-10-21/ Accessed on December 5, 2021.

- Stanway, David (2021). China’s giant state-owned companies struggle to align climate rhetoric with reality. November 1. URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinas-giant-state-owned-companies-struggle-align-climate-rhetoric-with-reality-2021-11-01/ Accessed on December 8, 2021

- Stanway, David (2021). Stop funding coal abroad, NGO group tells top investor Bank of China, September 14. URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/stop-funding-coal-overseas-ngo-group-tells-top-investor-bank-china-2021-09-14/ Accessed on December 1, 2021

- The Hindu (2021). China coal prices hit record high as floods add to supply woes. October 13. URL: https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/china-coal-prices-hit-record-high-as-floods-add-to-supply-woes/article36978126.ece Accessed on December 2, 2021.

- Volcovicci, Valerie, Brunnstrom, David and Nichols, Michelle (2021). In climate pledge, Xi says China will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad. September 22. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/xi-says-china-aims-provide-2-bln-vaccine-doses-by-year-end-2021-09-21/ Accessed on December 1, 2021.

- Xie, Echo (2021). The local government failures behind China’s power crisis. South China Morning Post. September 30. URL:https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3150631/local-government-failures-behind-chinas-power-crisis Accessed on December 12, 2021.

- Ye Qi and Jiaqi Lu (2016). The end of coal-fired growth in China. August 14. URL: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2016/08/04/the-end-of-coal-fired-growth-in-china/ Accessed on December 6, 2021.