Introduction

All countries face multiple policy choices in their early years of development. One of the first policy choices they face is in resource allocation—should resources be allocated to agriculture or to manufacturing to accelerate the country’s development process? Typically, development includes a structural transformation of economies from least developed, where agriculture is the largest contributor to gross domestic product (GDP), to high-income where agriculture occupies less than 5 percent of GDP. This structural transformation was witnessed by England in the 18th century, Japan in the late 19th century and east Asia in the late 20th century. This article first tries to understand whether agriculture can foster economic development and then explores if such a model is suited for India.

Agriculture-led development models

Unlike Keynesian development models that advocate savings and investment, an agriculture-led development model argues for the development of the agricultural sector to fuel the rest of the economy. This implies that resource allocation will be in favour of agriculture. It is particularly useful for states that are predominantly agrarian like in the north-eastern region where 70 percent of the region’s workforce is engaged in agriculture. In this model, advocated by Arthur Lewis, agriculture is first developed until a structural change of the labour force occurs – where labour moves out of agriculture into more productive sectors like industry or services. However, Arthur Lewis’ two-sector model limits the role of agriculture to supplying surplus labour to more modern and high productive sectors such as manufacturing, emphasising labour productivity and increased output. Subsequent theories recognise the central role that agriculture plays in launching the development process in developing countries by providing linkages to non-agricultural sectors. Johnston and Mellor (1961) for example, view agriculture as central to the development process, providing surplus labour, supplying food and contributing to foreign-exchange, lacking which development cannot take place. It is worth recalling that in the initial stages of development, manufacturing is agriculturally related.

Empirical evidence from cross-country studies show that agriculture is over two times as effective in reducing poverty than either the manufacturing or service sectors[i]. It increases labour productivity and wages, and produces savings that are invested in other sectors. Drawing from this argument, agriculture plays a key role in escaping a “poverty trap” as it is labour intensive, employing a large section of the population. It is also suggested that “GDP growth originating from agriculture has a much larger positive effect on expenditure gains for the poorest households than growth originating in the rest of the economy”.[ii]

Harris and Todaro (1970) and Mellor and Johnston (1984) argue that encouragement of agriculture in the initial stages of the development cycle, increases agriculture-dependent household income, increases their spending power and eventually reduces overall poverty. In essence, a four transmission mechanism for poverty-reducing growth occurs. First, food becomes cheaper and farm incomes increase thereby creating more jobs, and finally incomes multiply which stimulates economic diversification. What is clear is that structural transformation from agriculture to manufacturing and services is inevitable as a country develops. However, this growth should be corresponded with an equal share of labour force out of agriculture into more productive sectors. Unfortunately, these theorists continued to view agriculture as the handmaiden of industrialisation. There is a need to re-think this paradigm with an explicit focus on agriculture for development rather than the role of agriculture in industrialisation.

Agriculture and Economic Development

The pertinent question is can agriculture foster economic development? Empirical evidence points to the pro-poor growth that only agriculture can provide, as it directly affects small and medium landowners and does not rely on a trickle-down effect. Importantly, poverty reduction emerges from rural areas. Empirical evidence from cross-country studies show that agriculture is over two times as effective in reducing poverty than either the manufacturing or service sectors.[iii] It increases labour productivity and wages, and produces savings that are invested in other sectors. Drawing from this argument, agriculture plays a key role in escaping “poverty trap” as it is labour intensive, employing a large section of the population. It is also suggested that GDP growth originating from agriculture induces growth among the 40 percent poorest in a country.[iv]

Increased land productivity is inversely proportional to poverty.[v] Irrigated farmlands produce more crop and “diversify their cropping systems”, increasing their earnings, as compared to non-irrigated farmlands.[vi] The earnings are spent within the local community, having linkages to poverty reduction across sectors. However, one needs caution in forming a causal relationship between poverty reduction and irrigated farmlands and non-irrigated farmlands, as other factors such as access to credit and level of education also affect poverty reduction.

In the early stages of development, agriculture is the lead foreign exchange earner through its exports. In regions that are rich in natural resources and where labour is abundant but infrastructure is poor and private investment is minimal, agriculture as a development strategy to foster economic growth is most suited as it provides a comparative advantage in transitioning to primary commodities manufacturing. India’s north-eastern region will benefit from this comparative advantage.

Johnston and Mellor (1961) outlined five ways by which agriculture can promote economic development. The first is meeting increased food demands as a country develops (food security), second, as “a means for increasing income and foreign exchange earnings”, third and fourth, in contributing capital and labour to advanced sectors, and fifth, by stimulating the economy through increases in farm wages.[vii] Three of the five means continue to view agriculture in an exploitative role, used only to feed other sectors, but the authors emphasise that each mean plays an equal role. Underlying Johnston and Mellor’s argument are the backward and forward linkages to non-agriculture sectors, particularly when excess income from increased agricultural production is spent on local goods and services. The authors’ note that income elasticity of demand for food is higher in developing countries, implying a greater demand for agricultural produce as a country develops. Their argument views agriculture as stimulating a chain reaction for development. As a country grows, its population demands more agricultural produce which is met by farmers, thereby increasing their surplus income as well as their ability to demand other goods and services that are locally produced. Others call for greater government intervention when pursuing an agriculture-led development strategy, especially to help maintain the growth of agriculture and to raise productivity and incomes.[viii] Overall, a strong positive link is found between agriculture and long-term economic development in both Asia and Africa, and is stronger with increased trade openness.[ix]

Ultimately how successful such a model is will depend on the absorptive capacity of the manufacturing sector – how effectively can they make use of the excess agricultural inputs. Essentially, how will the manufacturing sector make use of the structural change that is assumed to occur? Empirical evidence points to a positive relationship between competitiveness and development. Therefore, the more competitive the manufacturing sector (or other productive sectors), the more the benefit from agricultural-led development models. Policy implications for countries therefore is to ensure that the structural transformation of labour occurs. Particularly for countries like India that has a growing population it is important to fast-track this labour-shift. Paradoxically, the process of development eventually limits the role of agriculture and favours industrialisation.[x]

Is Agriculture-led Development Suitable as a Model for India?

40 percent of India’s workforce is engaged in agriculture. 328.73 million hectares of land is suitable for agricultural cultivation in India. Of this 64.03 percent is cultivated, and 67 percent of this is irrigated either by canals or tube-wells. Majority (68.45 percent) of this land is owned by marginal holders. In 2018-19, the agriculture sector grew at 2.4 percent at constant 2011-12 prices. The percentage share of value of agricultural exports to national exports is 11.90 percent. Based on Census data, between 1951 and 2011, India’s population grew by 231 percent, whereas those engaged in agriculture declined by a mere 21 percent.

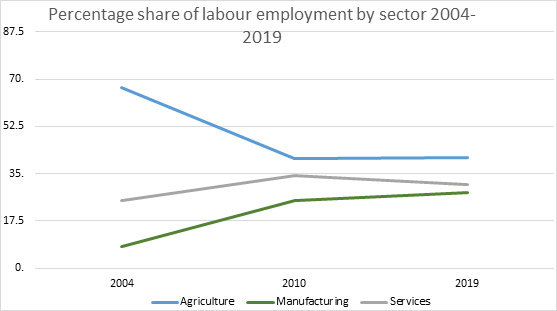

Figure 1: Share of labour employment by sector from 2004 to 2019

Source: Author’s own compilation based on data from NSS survey’s in 2004, 2010 and 2019.

What do these statistics imply? As seen in Figure 1, India is an agricultural country, with majority of its population engaged in the agricultural sector. A shift of surplus labour to more productive sectors is evident, albeit gradually. A positive trend is that between 2004-2019 labour shift is converging, implying a more even distribution of labour. Between 2010 and 2019, labour employment in agriculture has been stable, whereas that of services has declined. It is likely that labour absorption into manufacturing was from services rather than from agriculture. Growth in labour employment in manufacturing is a positive sign, but benefits are more when labour is absorbed from agriculture as it is easier to skill workforce in manufacture sector than in services.

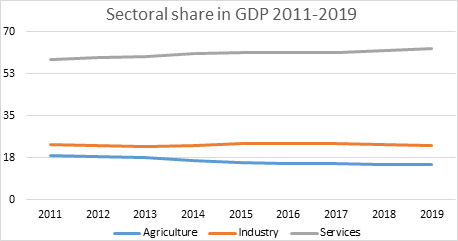

Figure 2: Sectoral shares in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) between 2011 and 2019 based on the 2011-12 series.

Source: Author’s own compilation based on data from the Reserve Bank of India[xi]

Figure 2 shows the share of GDP by various sectors between 2011 and 2019, based on the 2011-12 series. Although the RBIs classification is more detailed and includes agriculture, mining, manufacturing, electricity, construction, transport, finance, and public administration, for the purpose of this paper the sectors were merged and classified into agriculture, industry and services. The share of industry marginally increased in the 2011-2019 period, while services saw an increase from 59 to 63 percent and continues to maintain an overwhelming lead. Agriculture on the other hand decreased from 19 percent in 2011 to 14.6 percent in 2019, yet employs a disproportionately large number of people.

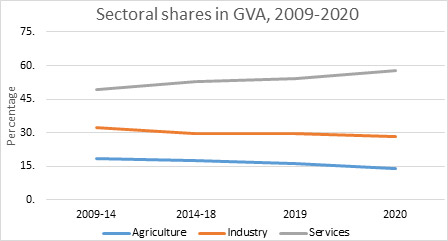

Figure 3: Sectoral shares in Gross Value Added (GVA) between 2009 and 2020

Source: Author’s own compilation based on data from the 2020-21 Budget[xii]

However, GDP does not reveal the entire story. Examining Gross Value Added (GVA) gives a more accurate picture as it takes into account the real contribution of each sector and is therefore a better measurement of a nation’s economic performance. As seen in Figure 3, a structural change is evident but this is seemingly driven by the service sector. The share of agriculture in the total GVA has declined from 2009-2019 on account of a high growth in the service sector. Growth in the tertiary sectors is highest between the 2014-2020 period. Interestingly, both agriculture and industry declined at roughly the same rate in this period. This is because agriculture output affects industrial growth. High growth in non-agricultural sectors and decline in agriculture is common as a country develops. However, the growth in services is not in proportion to the structural change in labour as seen in Figure 1. A policy implication is to further train labour that moves out of agriculture so as to enable their quick employability in services or industry.

The Green Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s in India increased agricultural productivity in select states. This spurred growth in the agricultural sector but reduced urbanisation and manufacturing growth.[xiii] Agricultural productivity growth increased proxies for rural public goods provisions in these districts, including education, better roads and health-care. Rural agricultural wages improved but at the cost of increased inequality in land ownership. Agricultural productivity may have increased but at the expensive of manufacturing. The Green Revolution “impeded structural transformation across Indian districts”.[xiv] Mistakes from the Green Revolution cannot be repeated.

It is clear from Figure 1, 2 and 3 that India’s path to development has, thus far, been driven by the services and manufacturing sectors. Agriculture continues to play an important role largely due to the enormous number of people dependent on it for their livelihood, but has not been at the forefront of development. Multiple policy implications emerge.

First, India’s agricultural sector is dependent on rainfall. A bad monsoon affects agricultural production, while pre-monsoon rainfall bodes well for kharif sowing. Agricultural is critical for macroeconomic stability and for sustained growth. Typically, industry responds positively to a good agricultural year. Therefore, there is a need to make agriculture less dependent on monsoon and encourage other irrigation and water-harvesting methods that ensure stable produce every year.

Second, supply bottlenecks will need to be addressed as well as create direct farm-to-fork supply chains. This will ensure that farmers are given the choice to sell directly to their customers demanding a higher price and eliminating dependency on middle-men.

Third, given that a large majority of Indian farmers are marginal, the focus must be shifted towards increased agricultural productivity per hectare. Research need to focus on increasing agricultural productivity and transferring this knowledge to farmers. Focus must also be directed towards “more crop per drop”. Encouraging farmers to diversify to higher-value commodities will be a key factory in increasing agricultural growth and income, thereby reducing poverty.

Fourth, markets will be need to be further developed and restrictions on internal and external trade loosened. Partnering with the private sector particularly for marketing, value chain and agro-processing is important. The private sector will have both the funds and incentive to manage cold storage units ensuring long-lasting agricultural produce.

Farm Laws 2020

To give the agriculture sector a boost, a set of laws were passed late last year including The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement On Price Assurance and Farmers Services Act 2020, The Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act 2020, and The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020. Each of these Acts aim to clear the bottlenecks in Indian agriculture that were highlighted in the previous section. Below, the first two Acts are examined.

The first Act gives farmers the liberty to enter into agreements to produce agricultural products that are demanded by the market, without compromising on the farmer’s rights. Likely outcomes are better pricing for producers and consumers, as well as improved quality of produce for consumers. Farmers will benefit from market analysis to inform actions to diversify land use, will be better equipped to manage risks of uncertain produce, are more likely to adapt to newer technologies and to engage in land pooling. The private sector is likely to encourage insuring agricultural produce, shifting the risk of a bad crop year away from the farmer. Moreover, involvement of the private sector incentivises the creation of superior value chains.

The second Act removes barriers to trade and allows farmers to sell their produce anywhere in India. This will ensure remunerative prices and competitive trading, paving the way for alternatives to non-traditional physical trading platforms. It will allow the highly profitable farm-to-table movement to kick-off in India. Free markets in agriculture are not inherently bad. They give producers more freedom and choice in trading. Involvement of the private sector in agriculture ensures efficient value and supply chains, better marketing and profits to all players along the value chain. However, to truly reap benefits from a free market, farmers will have to be informed of market developments, true pricing and value of their produce, and will need to be sufficiently trained in marketing.

These farm laws conform to a globalised world run on free-market principles, giving farmers more choice and freedom to sell their produce. If implemented effectively, potential outcomes include crop diversification, maximum production, efficient use of resources, increased farm income, access to credit and insurance, and reduced poverty. Additional potential outcomes for the sector include efficient supply chains, storage facilities and value chains. Consumers on the other hand will benefit from competitive prices and improved quality produce. These measures will not only help spur the agriculture sector, but will also give a boost to the manufacturing sector, as they are intricately connected. The new laws can form the basis for an agricultural-led development model.

Conclusion

An agricultural-led development model promises increased incomes, reduced poverty, development of rural non-farm sector, strengthened domestic production base for industry, food security, increased trade, and better balance of payments. In particular, its impact on food price stability and contribution to total factor productivity for the entire economy cannot be ignored. It is a model for pro-poor growth which is driven from the bottom, instead of relying on a trickle-down effect to occur. Such models have worked in Asian economies like Japan, South Korea and Malaysia and bodes well with a growing economy like India. Moreover, growth in agriculture supports growth in industry and not the other way around. However, India will have to ensure a quick structural change in labour to fully benefit from such a model.

As seen in this paper, the decline in agricultural contribution has not been in proportion with the decline of workforce engaged in agriculture. Current government initiatives to skill workforce are welcome, but this needs to be enhanced to ensure faster absorption of the workforce particularly into manufacturing and services. Equally important is to open trade as openness to trade is directly proportional to higher growth, increased income and reduced poverty. To fully reap the benefits of an agriculture-led development model, attention must be given to increasing farm productivity, particularly since majority of Indian farm holding is marginal. In these regards, the Farmers Bill 2020 is only the beginning of an agricultural-led development revolution, but must be complimented by structural change, openness to trade, skilling of workforce, crop diversification and above all, increased productivity. Ultimately, the success of such a model will depend on the absorptive capacity into the manufacturing and service sectors.

This paper has been developed from a previously written article on a similar topic by the same author.

Author Brief Bio: Shreya Challagalla is Senior Research Fellow, India Foundation.

[i] See arguments on agriculture and poverty and economic growth from Christiaensen et al (2006); Timmer and Akkus (2008); Diao, Hazell and Thurlow (2010); World Bank (2007)

[ii] See Janvry and Sadoulet (2010) pg 6, who use data to provide evidence of agriculture’s contribution to reduction in poverty at the sectoral and household levels.

[iii] See Christianensen et al (2006); Timmer and Akkus (2008); World Bank (2007)

[iv] Janvry and Sadoulet find that the effect on poverty reduction amongst the poorest is highest when GDP originates from agriculture.

[v] Ibid., also see Zeng et al (2015)

[vi] See Bacha et al (2011) pg 9

[vii] See Johnston and Mellor (1961) pg 572

[viii] Timmer (1992) reviews three stages of thought on the role of agriculture in economic development, and argues that it is not enough to leave agriculture to market forces and that timely government policy interventions are required if agriculture is to play a stimulative role in economic development.

[ix] See Awokuse’s ‘Does agriculture really matter for economic growth in developing countries?’

[x] See Kuznets (1973); and Timmer and Akkus (2008)

[xi] The entire dataset may be found here – https://dbie.rbi.org.in/DBIE/dbie.rbi?site=home

[xii] Refer to Chapter 1, ‘State of the Economy’ in the 2020-21 Budget which can be accessed here – https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2020-21/economicsurvey/doc/vol2chapter/echap01_vol2.pdf

[xiii] See Moscana (2019) who compares structural change data across and within countries

[xiv] Ibid, pg 3

References

Awokuse, T.O (2009) ‘Does Agriculture Really Matter For Economic Growth In Developing Countries?’, paper presented at American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Milwaukee, 28 July, doi:10.22004/ag.econ.49762 (accessed 10 January 2020)

Barah, B.C (2006) ‘Agricultural development in North-east India: Challenges and Opportunities’, ICAR Policy Brief 26,

http://www.ncap.res.in/upload_files/policy_brief/pb25.pdf (accessed 17 January 2020)

Byerlee, D; Janvry, A; and Sadoulet, E (2009) ‘Agriculture for Development: Toward a New Paradigm’, University of California at Berkeley,

https://are.berkeley.edu/~esadoulet/papers/Annual_Review_of_ResEcon7.pdf

Christiaensen, L; Demery, L, and Kuhl, J (2006) ‘The role of agriculture in poverty reduction: an empirical perspective’, World Bank,

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/153831468313862932/pdf/wps40130BOX0311113B01tell0JS0when0done1.pdf (accessed 10 January 2020)

Diao, X; Hazell, P, and Thurlow, J (2010) ‘The Role of Agriculture in African Development’, World Development 38: 1375-1383, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.011 (accessed 10 January 2020)

Government of India (2020), ‘State of the Economy’, Economic Survey 2019-20 (2): 1-35.

Jana, H., and Basu, D (2018) ‘Agricultural backwardness analysis of North-east India: A cause of concern for national development’, International Journal of Current Research 10 (12): 76825-76831.

Janvry, A, and Sadoulet, E (2010) ‘Agricultural Growth And Poverty Reduction: Additional Evidence’, The World Bank Research Observer 25: 1-20, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40649308 (accessed 10 January 2020)

Johnston, B.F., and Mellor, J.W (1961) ‘The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development’, The American Economic Review 51: 566-593, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1812786 (accessed 10 January 2020)

Kuznets, S (1973) ‘Modern Economic Growth: Findings and Reflections’, The American Economic Review 63: 247-258, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1914358 (accessed 12 January 2020)

Moscana, J (2019) ‘Agricultural Development and Structural Change, Within and Across Countries’ MIT Economics, http://economics.mit.edu/files/13482 (accessed 10 February 2021)

RBI (n.d) ‘Database on Indian Economy’, https://dbie.rbi.org.in/DBIE/dbie.rbi?site=home

Timmer, C.P, and Akkus, S (2008) ‘The Structural Transformation as a Pathway out of Poverty: Analytics, Empirics and Politics’ working paper 150 for Center for Global Development, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/91306/wp150.pdf (accessed 14 January 2020)

Timmer, C.P (1992) ‘Agriculture and economic development revisited’, Agricultural Systems 40: 21-58, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-521X(92)90015-G (accessed 10 January 2020)

World Bank (2007) World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development, Washington DC: World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5990 (accessed 10 January 2020)