Introduction

India’s trade policy has undergone significant changes in the past five years, raising the crucial question of whether its tariff regime is driven by protectionist instincts or a pragmatic economic strategy. As a senior industry professional with three decades of experience, and responsible for strategic decisions in a USD 15 billion manufacturing company, I have observed how tariff policies can shape competitive landscapes.

India’s policymakers are striving to balance the protection of domestic industries with the benefits of trade liberalisation. On one hand, the government has raised import duties on various goods and invoked trade defence measures (such as anti-dumping investigations) to safeguard local producers. On the other hand, it has pursued export targets, established new trade agreements, and offered production incentives to integrate with global markets. This brief report examines India’s tariff strategy through a macroeconomic lens to assess whether recent policies represent protectionism or a pragmatic recalibration. Key indicators—from comparative advantage metrics to export composition, tariff structures, and industry challenges—are evaluated. Lastly, strategic recommendations are provided for businesses to establish competitive advantage amid India’s evolving tariff and non-tariff trade policies.

India’s Comparative Advantage and Trade Specialisation

India’s trade profile reveals areas of both strong comparative advantage and unrealised potential. Comparative advantage indicators show that India excels in certain skilled industries and services. For example, India has world-leading competitiveness in IT and business process services, capturing a major share of global IT exports. In manufacturing, India performs well in pharmaceuticals and transport vehicles, sectors that leverage the country’s skilled labour and large-scale industry. These areas demonstrate India’s revealed comparative advantage (RCA) indices, which are high and reflect global export shares exceeding its world export share. In contrast, labour-intensive manufactures, such as textiles and apparel, have lagged despite India’s inherent advantages in these sectors. For instance, India’s share of world exports in apparel has stalled, even though low-cost labour and traditional know-how suggest it could be higher. This divergence indicates that while India has specialised successfully in certain medium- and high-tech goods, it has not fully capitalised on its potential in all areas.

Trade specialisation metrics present a mixed picture. India’s share of global merchandise exports remains modest at approximately 1.8% as of 2023, having only slightly increased from 1.7% in 2014. (By comparison, China accounts for over 14% of world exports.) India’s ranking among merchandise exporters improved from 19th to 17th globally during this period. The country’s export basket is fairly diversified, with a moderate concentration in its top products. India’s export complexity (a measure of the range and sophistication of exports) has improved over time, reflecting a shift towards higher-value goods. However, the overall scale of India’s exports remains low relative to the economy’s size – merchandise exports amount to only around 13% of GDP (2021-22), down from roughly 17% a decade earlier. This indicates that India’s trade specialisation is still limited, and the economy is less export-driven than its East Asian counterparts. In summary, India demonstrates clear comparative advantages in specific sectors (pharma, refined petroleum, IT services, etc.) but has yet to fully translate these into a dominant global trade position. Addressing internal bottlenecks – such as infrastructure gaps, technology adoption, and skills – could enhance India’s trade specialisation in both traditional and emerging industries.

India’s Tariff Strategy: Protectionist or Pragmatic?

India’s recent tariff actions have sparked debate about whether they represent a protectionist shift or a pragmatic policy response to global and domestic challenges. Factually, India did increase many import tariffs in the late 2010s, reversing a lengthy period of post-1991 liberalisation. The simple average of India’s tariffs rose by approximately 25% over the last decade, reaching 11.1% in 2020-21. This increase marked a departure from the steady tariff reductions of prior decades and has been described as a “creeping rise in protectionist tariffs.” In budgets from 2018 onwards, the government raised customs duties on products like electronics, toys, furniture, auto parts, and textiles, explicitly encouraging domestic manufacturing under the “Make in India” and Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) initiatives. Such measures—alongside frequent anti-dumping actions (India initiated 233 anti-dumping investigations in 2015–2019 alone)—have led many observers to label India’s trade approach increasingly protectionist. Even the World Bank noted in 2024 that India’s import tariffs on key inputs (from China and others) raise costs and undermine its participation in global value chains.

However, the government defends its approach as pragmatic and strategic rather than protectionist. Officials argue that selective tariff hikes are intended to nurture nascent industries, correct trade imbalances, and reduce import dependence in sensitive sectors, not to isolate India from trade. In practice, India’s trade policy in recent years appears to blend protectionism with pragmatism. On one side, tariffs on items such as electronics, toys, and furniture have been raised to bolster domestic producers, and import bans or restrictive origin rules have been imposed (for instance, stricter rules of origin were implemented to prevent Chinese goods from routing via FTA partners). These measures indeed protect local industry but risk inviting retaliation or higher costs.

On the other hand, India has offered tariff concessions on inputs (e.g. reducing duties on raw materials for textiles and steel in budgets). It has utilised production-linked incentive (PLI) schemes instead of blanket tariffs to encourage domestic manufacturing in electronics, pharma, and solar panels. Such calibrated steps can be considered pragmatic industrial policy consistent with WTO rules (since PLI subsidies are targeted) rather than blunt protectionism.

Composition of India’s Exports: Landscape of Manufactured Goods

The landscape of India’s exports has evolved significantly in recent years, with manufactured goods now dominating the export basket. In the fiscal year 2021–22, India’s merchandise exports surged to a record $418 billion, rebounding strongly after the pandemic. Manufactured products (industrial goods) constitute the bulk of these exports, alongside notable contributions from agriculture and minerals. Within manufacturing, a few categories stand out as pillars of India’s export profile:

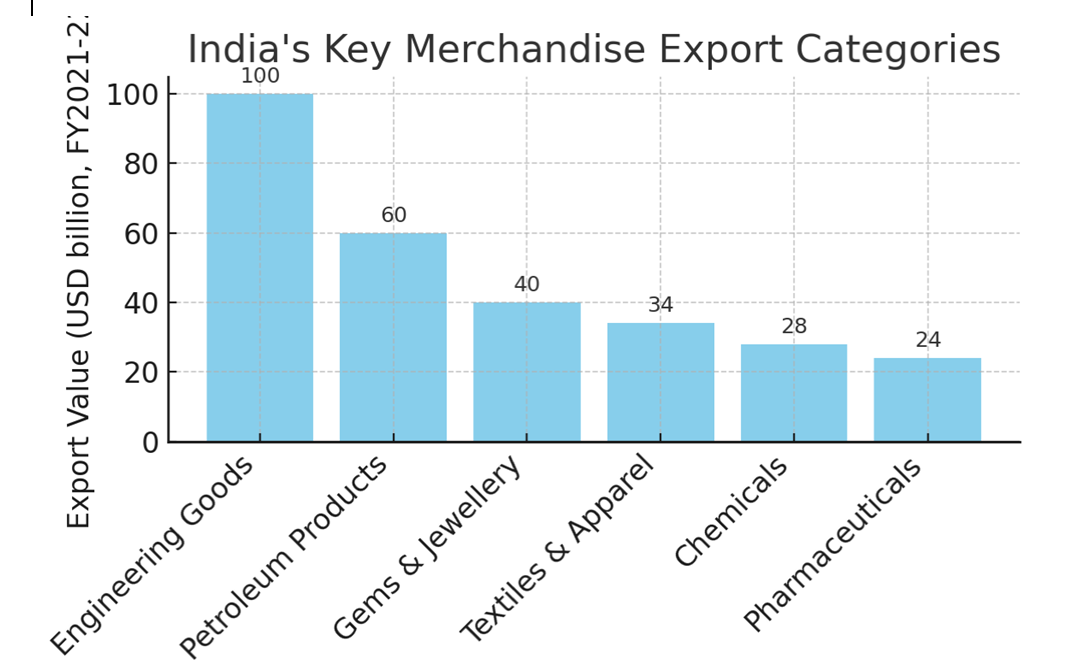

Engineering goods, petroleum products, gems and jewellery, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals consistently rank as the top earners. Engineering goods—a broad category that includes industrial machinery, automobiles and auto parts, iron and steel products, among others—constitute the largest segment, reflecting India’s strength in heavy industries and automobile manufacturing. In 2021-22, India’s engineering exports surpassed $100 billion for the first time, accounting for approximately one-quarter of total merchandise exports.

Due to India’s large oil refining capacity, petroleum products are the second principal component. India imports crude oil but exports substantial volumes of refined fuels (diesel, petrol) and petrochemicals. Elevated global oil prices and increased refining output caused petroleum product exports to surge over 140% in 2021-22, reaching an estimated ~$60 billion. Gems and jewellery, particularly cut and polished diamonds and gold jewellery, represent another traditional export forte (around $40 billion annually), leveraging India’s skilled artisan workforce in the diamond polishing hubs. Chemicals and related products (including speciality chemicals, plastics, etc.) and pharmaceuticals have expanded rapidly, contributing approximately $50+ billion. Notably, India is a top global supplier of generic medicines (pharma exports ~$24–25 billion) and an emerging player in organic chemicals.

Meanwhile, textiles and apparel – once a leading export sector – have shown modest performance (estimated at over $30 billion), yielding ground to countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam in recent years. India’s agricultural exports (rice, sugar, spices, etc.) and software services exports are also significant, but the focus here is on merchandise. The chart in Figure 1 illustrates the scale of key merchandise export categories (values for FY2021- 22), highlighting the dominance of engineering goods and refined petroleum among exported products.

Figure 1: India’s top merchandise export categories by value (FY2021- 22).

Engineering goods and other manufactured products constitute the majority of India’s exports. Petroleum refinery products are a significant export because of India’s refining industry. Traditional sectors such as gems and jewellery, alongside textiles, continue to hold importance, while chemicals and pharmaceuticals are rapidly growing segments.

This export composition underscores that manufactured goods drive India’s trade, contrary to the outdated image of India as primarily an exporter of primary goods or services. Over 75% of India’s merchandise exports are in manufacturing categories (including refined petroleum). This diversification into manufacturing has been a gradual structural change: policy reforms since 1991 enabled industries such as autos, pharma, and steel to become internationally competitive. By the mid-2010s, India had established a foothold in medium- and high-tech exports; for instance, it is among the top five exporters of generic pharmaceuticals, and its auto industry exports millions of vehicles and components annually. India’s performance in these sectors demonstrates improved technological depth, though challenges remain (e.g., low R&D spending at 0.9% of GDP hampers the move up the value chain).

Another encouraging sign is the broadening of India’s export destinations. Indian goods are now exported to over 115 countries, covering 46% of all world economies. Traditional markets like the U.S. and EU still dominate (the EU alone accounts for ~12% of India’s goods trade), but India has expanded exports to emerging markets in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. This diversification helps reduce dependence on a few markets and indicates a maturing export sector. Still, India’s export intensity (exports/GDP) lags behind its peers – a concern for long-term growth.

The government’s $400 billion export target (achieved in 2021-22) was driven by rises in global commodity prices and a post-COVID demand recovery; however, maintaining high growth will require improvements in competitiveness. Notably, India’s share of world exports in certain labour-intensive goods (such as apparel and leather) has stagnated or declined, indicating that domestic bottlenecks (infrastructure, logistics, compliance costs) undermine those sectors’ advantages. Conversely, India’s success in skill-intensive goods (pharma, engineering) demonstrates what can be accomplished with the right mix of entrepreneurship and supportive policy.

In summary, India’s export landscape is characterised by a diverse, manufacturing-led basket, with several star sectors compensating for weaker areas. This composition also reflects India’s natural endowments and policy choices – abundant labour and jewellery craftsmanship support the gems and textiles industries; large refineries and pharmaceutical firms have developed from earlier policy initiatives. The key for India will be to deepen its comparative advantages (e.g., ascending the value chain in electronics, machinery, chemicals) while revitalising its competitiveness in job-rich sectors like apparel. The tariff strategy will play a crucial role here: high tariffs on inputs or capital goods could undermine export competitiveness, whereas supportive trade policies could assist.

Indian manufacturers integrate into global supply chains and maintain their export momentum.

Challenges Encountered by Indian Industries under Current Tariff Policies

India’s present combination of tariff and trade policies presents several challenges for domestic industries, impacting their cost structures, market access, and integration into supply chains.

Higher Input Costs and Inverted Duty Structures: A recurrent complaint of Indian manufacturers is that import duties on raw materials and components often raise their input costs, making final products less competitive. The existence of inverted duty structures (IDS) – where import tax on inputs exceeds that on finished goods – is particularly harmful. As noted, about one-third of products in sectors like electronics, chemicals, textiles, and metals in India face IDS. This means a textile producer might pay a 10% duty on imported fabric, but the finished garment faces, say, a 5% duty when imported – a recipe for undermining domestic manufacturing. Such tariff anomalies “leak” cost competitiveness, encouraging imports of finished goods and discouraging local value addition. While the government has started reviewing and correcting these (a comprehensive tariff review is underway), many industries still struggle with high duties on essential inputs like electronic components, speciality chemicals, or machine tools. Until resolved, this challenge limits Indian firms’ ability to scale up and become export-competitive.

Export Competitiveness and Global Value Chains (GVCs):

The integration of Indian industry into global value chains remains limited, mainly due to tariff policy. Higher tariffs not only increase domestic costs but can also provoke retaliatory barriers abroad. Moreover, a protectionist stance may result in India being excluded from trade arrangements that facilitate GVC integration. For instance, rising tariffs since 2014 have been cited as a factor that could exclude India from emerging supply chains (such as the Quad’s semiconductor initiative) unless reversed.

Many multinational firms still regard India primarily as a local market rather than an export base, partly because India’s tariff and regulatory regime makes importing inputs and exporting outputs less seamless than, for instance, Vietnam. A Deloitte survey of global business leaders indicated that countries like Vietnam and Indonesia score higher than India as preferred investment destinations, specifically due to more open trade regimes and easier business climates. Thus, Indian industries face the challenge that if trade policies remain relatively protectionist and cumbersome, they could miss out on foreign investment and partnership opportunities that GVC participation offers. This represents a strategic concern – modern manufacturing often entails components crossing borders multiple times, and tariffs can act as a tax on this process.

Policy Uncertainty and Frequent Changes: Industries value a stable policy environment for long-term planning.

In recent years, India’s trade policy has undergone frequent tweaks, including sudden tariff hikes in certain budgets, abrupt import bans (for example, on certain electronics or auto parts, citing quality concerns), and changes in export incentive schemes. The government’s amendment of the Customs Act in 2021 to enable bans on any goods “to prevent injury to the economy” is one such move that, while WTO-consistent in principle, adds regulatory uncertainty.

Businesses fear that unpredictable policies can heighten the risks of investing in export-oriented capacity. What if critical inputs are subjected to high duties or an export is banned to control inflation? A case in point was India’s ban on wheat exports in 2022 to ensure food security. While this decision benefited domestic consumers, traders and farmers were caught off guard. Similarly, incremental alterations in import tariffs, often announced with little notice, complicate efforts for industries to establish stable supply chains. The challenge for firms is to remain agile and compliant amid a multitude of changes to tariff lines, new quality control orders (non-tariff barriers), and evolving export incentive regimes, such as the recent shift from the MEIS to the RoDTEP scheme. Such uncertainty can deter investment, as companies may prefer more predictable jurisdictions for establishing manufacturing intended for export.

In summary, Indian industries today are in a transitional phase: they benefit from a large protected home market due to tariffs. However, many are striving to become world-class exporters, which requires reducing costs and integrating with global supply chains. The challenges highlighted—costly inputs (IDS), limited FTA benefits, policy uncertainty, and competitive disadvantages abroad—suggest that India’s tariff strategy, while providing short-term protection, might hinder firms in the long run if not calibrated correctly.

Industries such as chemicals, electronics, and textiles have explicitly pointed out that tariff protection alone cannot ensure global success and that complementary measures (infrastructure, skill development, innovation) are required. Encouragingly, the government recognises some of these pain points: the ongoing tariff review to rectify inverted duties and the pursuit of new FTAs are positive steps. However, until these measures materialise, Indian firms must navigate a challenging environment where domestic policy shields them at home but potentially handicaps them abroad.

Strategic Recommendations for Gaining Competitive Advantage

In light of the challenges mentioned above and the current tariff regime, Indian businesses—particularly large manufacturers and those engaged in global trade—should adopt strategies to create a competitive advantage while alleviating tariff-related disadvantages. Below are strategic recommendations for companies to prosper under India’s tariff and non-tariff trade policies:

- Focus on Operational Efficiency and Product Differentiation: When tariffs raise input costs or shelter a firm from competition, there exists a risk of complacency. Savvy businesses should utilise the protected period to enhance efficiency, quality, and R&D to better withstand competition in the long term. This involves investing in modern production technology, workforce training, and lean manufacturing to counteract cost disadvantages. By boosting productivity, Indian firms can narrow the cost gap that tariffs temporarily disguise. Furthermore, product differentiation is crucial – rather than competing solely on cost (where Chinese or other competitors might undercut), Indian companies can innovate and specialise in higher-value niches. For instance, in the textiles sector, instead of mass-producing basic apparel (where Bangladesh has an advantage), Indian firms could concentrate on technical textiles or fashion segments where they can command a premium. In chemicals, businesses are shifting towards specialty chemicals and formulations customised for client requirements, which face less direct competition and often inspire loyalty. These strategies enhance businesses’ resilience against both domestic import competition (if tariffs are lowered) and aggressive pricing abroad. Essentially, competitive advantage must stem from inherent strengths – quality, innovation, branding – rather than reliance on tariffs. Firms that accomplish this will discover that even if tariffs are reduced (as OECD and others recommend for India), they can maintain their position in the market.

- Advocacy for Tariff Rationalisation and Trade Facilitation: Industry leaders could actively engage with the government (through industry associations such as CII, FICCI, etc.) to advocate for a simpler, more rational tariff structure that benefits the broader economy. The ongoing anomalies, such as inverted duties, harm not only individual companies but entire value chains. By providing data and case studies to policymakers, businesses can push for the timely removal of such anomalies. Advocacy can also extend to urging the government to fast-track critical FTAs; for instance, an India-EU FTA would greatly assist sectors such as automobiles, textiles, and pharmaceuticals by reducing tariffs in that vast market. Additionally, firms should lobby for improved trade facilitation, including smoother customs processes, digital clearance, and infrastructure development at ports. Reducing non-tariff barriers and transaction costs can often be as significant as cutting tariffs. Some issues highlighted include alignment with international standards (to reduce rejections abroad) and increased transparency in trade policy changes. A collaborative approach, where industry voices its needs and works with policymakers, can create a win-win: policies that both protect and empower domestic industry in a sustainable way.

- Capitalising on Government Support Programmes: While tariffs are one tool, the government has introduced numerous programmes to boost industry that firms could capitalise on. The Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes in sectors like electronics, autos, pharma, and chemicals effectively provide financial rewards for scaling up domestic production and exports. By participating in PLI, companies can offset some disadvantages (such as higher input costs) through subsidy gains, which enhances overall competitiveness. Similarly, programmes for MSMEs, export promotion capital goods (EPCG duty exemptions), and refund of duties & taxes on exports (RoDTEP) help reduce the tax burden on exporters. Savvy firms will ensure they claim all eligible incentives and remain compliant with requirements to maximise these benefits. Over time, such support can help firms achieve global scale and competitiveness, after which they can thrive without protection. The recent success of mobile phone manufacturing in India – which went from near-zero to over $5 billion in exports in a few years, aided by tariffs on imports and PLI incentives – is a model that could be replicated in other sectors. Businesses should align their strategies with these national initiatives (for example, the push for green hydrogen or electric vehicle components) where they identify long-term potential, as they often come with tariff adjustments (low duties on inputs, high on finished imports) that favour early movers.

Conclusion

India’s tariff strategy over the past five years reflects a delicate balancing act. The nation has employed tariffs and trade measures to protect domestic industries and promote self-reliance, a stance that leans towards protectionism in the short term. Simultaneously, India’s long-term economic aspirations – to increase manufacturing’s share of GDP, integrate into global value chains, and become a $5 trillion economy in the near future – create a pragmatic need for openness and competitiveness. As this report has analysed, India’s comparative advantages are genuine but require nurturing through efficient policy, not permanent protection. The composition of exports demonstrates that India can succeed in diverse manufacturing sectors; however, challenges such as inverted duties and limited free trade access hinder industries from reaching their full potential.

India’s tariff strategy is not merely a binary of protectionism versus pragmatism; it rather exists on a spectrum where policy must continuously calibrate between the two. The next few years will likely witness further tariff rationalisation, more trade deals, and efforts to align with global standards – steps towards pragmatism that are already underway. Indian industry, for its part, should be prepared to capitalise on a more open yet competitive environment. With the right strategic responses, businesses can transform India’s tariff and trade policies into a foundation for securing competitive advantage, both domestically and on the global stage. This balanced approach – protecting where necessary and liberalising where possible – could effectively decode a tariff strategy that propels India towards high-quality growth and greater prominence in global trade, achieving the best of both protectionist caution and pragmatic engagement.

Author Brief Bio: Sundeep Kohli is SVP Finance at Indo Rama Ventures Ltd based in Thailand working closely with the founding family. Prior to that he worked with Reckitt Benckiser for almost 15 years in global finance roles across Japan, UK, China, Singapore amongst others and started his career with ITC Ltd. He is a Chartered Accountant by profession and an executive MBA from ISB, Hyderabad and has also done advanced business strategy courses from Harvard Business School.