Abstract:

Misconceptions surrounding the Vedic texts” endorsement of animal or human sacrifice, often attributed to the term “Bali,” are explored in this study. It is demonstrated that “Bali” holds a multitude of meanings, ranging from divine epithets to offerings and acts of selflessness. “Bali” encompasses a spectrum of interpretations, including its association with deities like Lord Vishnu, Lord Krishna, and Demon King Mahabali, as well as its connection to ancient cultures and practices. The study also examines the terms “Pashu” and “Bali.” The misinterpretation of these words is attributed to a lack of understanding, linguistic barriers, preconceived biases, and deliberate misrepresentations. To appreciate the wisdom and values inherent in Vedic traditions, it is crucial to approach their interpretation with an open, unbiased mind and respect for diverse perspectives. The Vedas, in essence, promote non-violence, reverence for all life, and universal harmony, which should be upheld in their study and practice.

Introduction

A segment of scholars, seemingly influenced by preconceived notions, assert that the Vedic texts condone rituals involving the sacrifice of animals or humans, often referring to it as “paśu” or “manav Bali.” This interpretation, however, stands on shaky ground. Much like the intricacies of the English language where a single word can take on diverse connotations, the Sanskrit term “Bali” too carries a rich tapestry of meanings and interpretations.In any language, the semantic versatility of words becomes apparent, their significance fluctuating in response to the context and usage.

Bali: A term with Multiple Meanings

Just as the English word “round” can denote a shape, a stage in an interview, a directionless motion, or perplexing dialogue, and “crane” can signify a bird, a mechanical lifting apparatus, or a tilting action, “Bali” illustrates this inherent linguistic flexibility by encapsulating a spectrum of interpretations. Let us now delve into these various facets of “Bali,”

In the Atharvaveda, “Bali” is used to signify the physical, mental, ethical, and emotional strength that originates from the Supreme, who is the ultimate source of strength.[1] In the Vishnusahasranama, a sacred compilation featuring 1,000 names of Lord Vishnu, we encounter “Bali”[2] as one of His appellations. This name underscores the facets of strength, power, and might that are inherently connected to Lord Vishnu.

Within the divine and spiritual realm, “Bali” serves as one of the 108 names attributed to Lord Krishna. This nomenclature transcends its worldly meaning, transforming into a profound divine epithet that encapsulates the qualities, attributes, and celestial manifestations of Lord Krishna. Each name within the list of 108 names holds a unique significance, representing a distinct facet of the deity invoked. In the case of Lord Krishna, the name “Bali” shines a spotlight on his divine strength, power, and unwavering commitment to safeguarding and upholding righteousness.[3]

“Bali” is one of the names of Balrāma,[4] the brother of Śrī Kṛṣna. “Bali,” when attributed to Balrama, embodies the connotation of strength and power. Renowned for his remarkable physical prowess and his pivotal role as a guardian, he is frequently portrayed brandishing both a plow (hala) and a mace (gada), which vividly symbolise his exceptional might and his unwavering dedication to defending and preserving righteousness. An additional layer of significance linked to the term “Bali” relates to the Demon King Mahabali,[5] who earned this epithet due to his unparalleled strength and power. It was his extraordinary might that bestowed upon him the titles of “Bali” or “Mahabali.” However, his reign came to an end with his defeat at the hands of Vishnu”s Vaman Avatar.

Within the grand narrative of the Mahabharata, we encounter the character “Bali,” portrayed as the Vanar Raja, or the king of monkeys.[6] To be more specific, he is identified as Anava, signalling his unique role and identity within the epic”s intricate storyline. Bali”s importance lies in his leadership role among the ‘vanaras’, a tribe of intelligent and robust humanoid monkeys. His presence and actions vividly underscore the vanaras valour and capabilities as formidable warriors and steadfast allies.

The Kathasaritsagara, known as the “ocean of streams of story,” features a mention of “Bali” and is a renowned Sanskrit epic tale that centres around Prince Naravahanadatta and his aspiration to ascend to the throne of the Vidyadharas, celestial beings. It is believed to be an adaptation of Gunadhya Brihatkatha, which comprises 100,000 verses, and this, in turn, is a part of a more extensive work encompassing 700,000 verses.[7]

“Bali” is the name of a Yakshagana, Mahamayuri Vidyarajni,[8] that is present in Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism. “Bali” is also linked to the sixth Prativasudeva,[9] an anti-heroic figure in Jain mythology. Prativasudevas are regarded as formidable beings who stand in opposition to the spiritual teachings and progress of Tirthankaras (spiritual leaders) and their disciples. The sixth Prativasudeva, known as “Bali,” is believed to possess immense strength and is portrayed as an antagonist in Jain narratives.

In tantric traditions, the name “Bali” is connected to the malevolent force governing Patala, the underworld realms. These realms are believed to be inhabited by a variety of beings, including Daityas, Nagas, and Rakshasas.[10] `The term “Bali” can also allude to a ascetic or hermit-like figure who, through the power of rigorous spiritual practices known as Tapas, dedicates himself to the welfare of the cosmos. With unwavering mental strength, he willingly sacrifices personal interests and desires, placing the well-being of humans, animals, birds, and the entire world at the forefront. This interpretation underscores his selflessness, unwavering commitment, and the profound influence of his actions.

“Bali” also alludes to the Kingdom of Bali, a historical sequence of Hindu-Buddhist realms that governed sections of Bali Island in Indonesia. This kingdom thrived from the 10th to the 20th centuries, boasting its Balinese monarchs and a distinctive court culture. These rulers harmoniously blended indigenous beliefs, reverence for their ancestors, and Hindu customs acquired from India via Java. This cultural amalgamation profoundly shaped the vibrant and diverse Balinese traditions we are familiar with today.[11]

“Bali” can additionally signify a mandatory tax or tribute collected from individuals and presented to the king. It symbolises a financial offering that citizens are obligated to provide to sustain the ruling authority. Typically, this tax is allocated for the upkeep, governance, and administration of the kingdom. The gathering of “Bali” plays a pivotal role in maintaining the financial stability and smooth operation of the royal establishment.[12] It also conveys the essence of a gift or offering, representing the act of voluntary giving, often in the form of a tribute or donation, to a deity, spiritual figure, or esteemed entity. This concept of “Bali” is deeply ingrained in religious and spiritual customs, where individuals manifest their devotion, gratitude, or reverence through the presentation of such gifts. These offerings may manifest in various forms, including food, flowers, incense, or valuable items. The act of offering a “Bali” holds a sacred significance, symbolising one”s unwavering dedication, devotion, and yearning to establish a profound connection with the divine.[13]

“Bali” extends beyond the mere act of worship and adoration, carrying a profound and transformative meaning. It encompasses the art of relinquishing one”s ego and wholeheartedly surrendering to the Supreme. This selfless surrender involves releasing attachments, overcoming addictions, shedding greed, anger, and other negative inclinations. By sacrificing these impurities, one embarks on a journey towards inner purification, aligning themselves with elevated virtues and spiritual values. The practice of “Bali” serves as a transformative path, urging individuals to transcend ego-driven desires and nurture a pure, selfless mindset. It is an invitation to release selfishness and embrace a profound connection with the divine, resulting in inner growth, spiritual ascension, and a harmonious existence.[14]

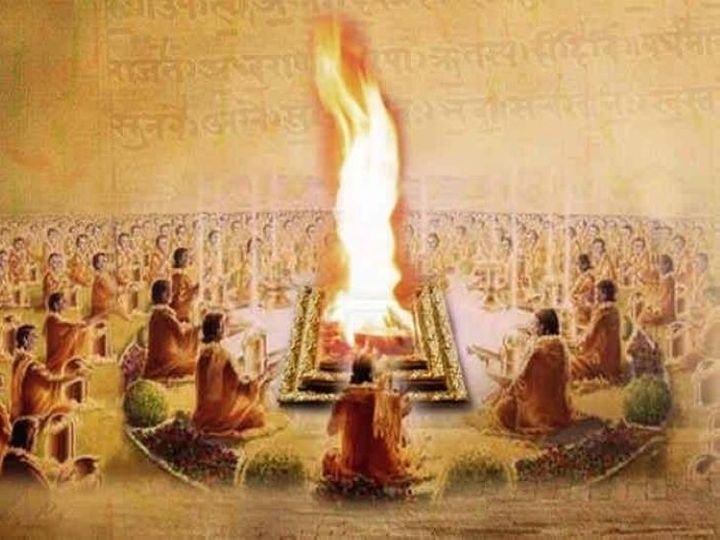

“Bali” carries a profound significance in the context of oblations presented during Yajna (sacrificial) rituals or in Havan (ritualistic fire worship). It encompasses the act of dedicating an array of materials, including ghee (clarified butter), grains, herbs, and other sacred substances, to the sacred fire. These oblations symbolise expressions of gratitude, devotion, and surrender to the divine forces. Through the offering of “Bali” into the fire, individuals aim to forge a connection with higher realms, invoke blessings, and convey their deep reverence for the divine. The practice of “Bali” in Yajna and Havan ceremonies is believed to purify the environment, elevate spiritual energies, and foster a harmonious atmosphere conducive to spiritual growth and well-being. It stands as a sacred bridge uniting the human and divine realms, nurturing a sense of unity, gratitude, and divine communion.[15]

“Bali” encompasses the daily ritualistic act of sacrificial offerings made as tokens of reverence and compassion to various beings. These offerings entail the provision of food, water, and essential provisions to sages, the impoverished, dogs, cows, and crows. This practice underscores the understanding that all living beings are interconnected and deserving of care and sustenance. When individuals present “Bali” to sages, it signifies their respect and the seeking of blessings from the wise and enlightened. Extending offerings to the less fortunate embodies acts of charity and compassion, providing support to those in need. The act of feeding dogs, cows, and crows is considered auspicious, honouring the sanctity of these animals. It is believed that such offerings usher in blessings, safeguard against negative influences, and generate positive karma. Through the practice of “Bali,” individuals nurture a sense of empathy, selflessness, and gratitude, acknowledging the intrinsic worth and interconnectedness of all living beings within the cosmic tapestry.[16]

“Bali” also implies the notion of self-sacrifice, often referred to as “Balidana.” This concept involves willingly forgoing one”s personal comforts, alms, food, or time for the betterment of others. It embodies the ethos of selflessness, compassion, and service toward those in need. Through the practice of Balidana, individuals prioritise the welfare of others over their own desires and willingly make sacrifices to provide support and uplift those in less fortunate circumstances. This can encompass actions such as providing food and resources to the hungry, extending assistance and care to the underprivileged, or dedicating time and effort to charitable causes. Balidana underscores the acknowledgment of our interconnectedness as human beings and the responsibility to contribute to the well-being of the community and society at large. Through acts of self-sacrifice, individuals nurture virtues such as empathy, generosity, and altruism, fostering a sense of unity and harmony in the world.

The act of presenting “Bali” encompasses more than merely offering uncooked or unbaked food to divine entities; it extends to sharing with other beings as well. This practice underscores the significance of selflessness and the art of giving before receiving. By offering “Bali” before partaking of any sustenance, it leaves a profound mental imprint, instilling in individuals the virtue of generosity and emphasising the importance of prioritising the well-being of others. It acts as a poignant reminder to cultivate a mindset of sharing and giving in every facet of life, nurturing compassion and fostering a profound sense of interconnectedness with all living beings.[17] The word carries the significance of a ceremonial food offering, particularly dedicated to Shiva, the protector of all beings, as prescribed in the Saivagamas. This ritual holds profound importance, involving the presentation of food to Shiva as an expression of reverence and devotion. The act of offering “Bali” to Shiva symbolises a profound spiritual connection and signifies the devotee’s complete surrender and devotion to the Divine presence of Shiva. Rooted in the Saivagamas, this sacred practice serves as a guiding principle for followers in their worship and unwavering devotion to the Divine.[18]

In the Rasashastra, a distinguished branch of Ayurveda dedicated to the study of chemical interactions among metals, minerals, and herbs, the term “Bali” that originates from the word “Bal” serves as a technical term denoting “wrinkles.” This specialised domain of Ayurveda delves into the intricate understanding of substances and their impacts on the human body, encompassing the comprehensive examination of wrinkles and potential remedies for them.[19]

In the domain of Gajayurveda or Hastyaayurveda, the term “Bali” is employed to denote oblations utilised in the treatment of elephants. This ancient branch of Ayurveda specifically focuses on the health and well-being of elephants, providing insights into their anatomy, diseases, and therapeutic measures. The use of oblations, including specific substances or offerings, forms an integral part of the treatment protocols designed to promote the vitality and recovery of these magnificent creatures.[20]

“Bali” refers to one of the topics dealt with in the Matrsadbhava, one of the earliest Shakta Tantric works from Kerala.[21] In Shaktism, “Bali” signifies the ritualistic worship of fifty-three deities in accordance with their designated compartments within a constructed Balimandapa. This sacred act involves offering Payasa, a preparation of rice boiled in milk, to these revered deities. The purpose of this worship is to honor and celebrate the divine entities who played a pivotal role in vanquishing the demon Vastu. Through this ritual, devotees express their devotion, seek divine blessings, and commemorate the triumph of good over evil in the cosmic realm.[22]

In the context of Vastushastra, “Bali” refers to a diagram consisting of eighty-one squares and a cluster of deities that are drawn on the ground as a blueprint for the construction of a structure. This diagram serves as a guide for the positioning and alignment of various elements within the building, ensuring harmony and auspiciousness. The inclusion of deities in the diagram signifies the spiritual aspect of the construction process and emphasises the belief in divine blessings and protection for the structure and its occupants. It is considered a sacred practice to follow the principles of the “Bali” diagram in Vastushastra to create a harmonious and auspicious living or working environment.[23]

Multiple meanings of Paśu

Let us now also have a look at the various meanings of the word Paśu. Within the philosophy of Shiva Siddhanta, the term “Pashu” is employed to denote an individual soul or sentient being, encompassing humans and other living creatures. It symbolises the finite and conditioned nature of the individual soul, which is ensnared in the cycle of birth and death and constrained by the limitations of the physical realm. In contrast, “Pati” refers to the Supreme Controller, which is Shiva, the ultimate divine reality. The objective of the individual soul is to surpass its restricted existence as a “Pashu” and achieve union with the Supreme, identified as Pati or Shiva. Through spiritual disciplines, devotion, and the realisation of one’s authentic self, the individual soul can progress toward liberation and the ultimate unity with Pati. This philosophy underscores the voyage of the soul from enslavement to liberation, from self-identification as the finite self to the recognition of its divine essence and unity with the Supreme.[24]

In the realm of the Shilpashastra, an ancient Indian treatise on art and architecture, the term “Pashu” is employed to encompass all embodied souls, including humans. It acknowledges that every living being, irrespective of its shape or species, falls under the category of Pashus. This concept is founded on the notion that all beings are interconnected and share a common existence. It underscores the unity among all life forms and acknowledges the innate divinity within each individual. This perspective fosters veneration and regard for all living beings, advocating for an all-encompassing and comprehensive approach to life and creation.[25]

Rishi Kashyapa is regarded as the progenitor or forefather of various beings, encompassing humans, animals, plants, and other celestial entities like Gandharvas, Devas, and Asuras. This belief symbolizes the common lineage and interdependence of all living entities, notwithstanding their varied shapes and manifestations.

In Vedic culture, the term “Pashu” is employed to encompass all beings in the world, signifying that its significance extends beyond just animals. It signifies the acknowledgment of the interconnectedness and shared existence of all life forms. “Pashu” represents the idea that all living beings, including humans, animals, and plants, are bound by the cycle of life and death and are subject to the laws of nature. Similarly, the word “Bali” holds multiple meanings and should not be confined to the interpretation of “animal sacrifice.” While the term “Bali” can be associated with offerings made in Vedic rituals, it does not imply the act of causing harm or bloodshed. Instead, these offerings symbolise acts of devotion, surrender, and selflessness. The purpose of such offerings is to establish a spiritual connection and seek blessings from the divine forces.

Why the terms Pasu and Bali are misunderstood

The misunderstanding of “Pasu” and “Bali” as animal sacrifice may have originated from a limited comprehension or cultural biases imposed on Vedic rituals. However, it is essential to acknowledge that Vedic rituals and the Vedas themselves promote veneration for all life forms and advocate for non-violence. They emphasise the principles of harmony, equilibrium, and spiritual progression. By embracing a holistic understanding of “Pasu” and “Bali” within the broader context of Vedic culture, we can recognise the profound wisdom and universal principles that underpin these age-old traditions. It is vital to approach the examination and interpretation of Vedic texts with an open perspective, honouring the diversity of interpretations and avoiding misrepresentations that could perpetuate misunderstandings regarding Vedic rituals and their genuine essence.

The reasons behind the misinterpretation of the word “Bali” could stem from various factors, including:

- Insufficient comprehension of the original texts, their context, philosophy, and the method by which they should be understood, considering factors like location, time, and circumstances.

- Inadequate knowledge of Sanskrit, the language in which the Vedas are written.

- Approaching the Vedas with pre-existing predispositions, biases, and preconceptions.

- Deliberate distortion of Vedic texts to advocate for violence, non-vegetarianism, and social divisions.

- Purposeful attempts to undermine the authority of the Vedas with the goal of eradicating Vedic culture, philosophy, and historical significance.

- Vedic texts often employ symbolism and allegory, which can be difficult to decipher, without a Guru.

Conclusion

This paper enumerates the intricate web of meanings interwoven into the term “Bali” as it exists within the Vedic tradition. This word encompasses a wide array of interpretations, spanning from divine appellations to symbolic offerings and selfless acts. The misunderstandings revolving around “Bali” and “Pashu” have their origins in several factors, including a limited grasp of the concepts, linguistic challenges, preexisting biases, and deliberate misrepresentations.

To gain a genuine understanding of the wisdom and values that underlie Vedic traditions, it is essential to approach their interpretation with an open, impartial mindset. The Vedas, at their core, advocate principles of non-violence, reverence for all life, and universal harmony. These foundational ideals should illuminate the path for studying and practicing Vedic traditions, with an emphasis on unity, compassion, and respect for all living beings.

Moreover, why the term “Bali” is misconstrued can be attributed to various influences, including a lack of comprehension of the original texts, language barriers, preconceived notions, deliberate distortions aimed at promoting violence or discord, and endeavours to diminish the significance of the Vedas.

Ultimately, it is crucial to acknowledge and address these influences when delving into Vedic texts, striving for a comprehensive comprehension, and embracing the profound wisdom and universal values they encapsulate. The Vedas stand as a testament to harmony, balance, and spiritual growth, emphasising reverence for all life forms and the interconnectedness of all existence. Approaching the Vedas with an open and unbiased mindset, while seeking knowledge and insight from qualified mentors and scholars who can provide accurate guidance and interpretation, is paramount. It is equally important to emphasise that the Vedas neither condone nor endorse actions that cause harm or sacrifice living beings for the sake of appeasing deities. Instead, these texts elevate animals to the status of the Supreme and advocate for their worship as manifestations of the Highest Reality. The teachings of the Vedas underscore universal compassion and discourage rituals, sacrifices, or ceremonies that inflict harm, disharmony, pain, or suffering on any living being. The essence of Vedic teachings lies in promoting harmony, respect, and veneration for all forms of life.

Author Brief Bio: Dr. Vandana Sharma ‘Diya’ is a Resident Fellow, Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla; Principal Researcher, Kedarnath, Central Sanskrit University, Delhi; Former Post-doctoral Researcher, Indian Council of Social Science Research and Former-Junior Research Fellow-Indian Council of Philosophical Research.

References:

- Ashtanghridayasamhita

- Atharvaveda

- Bhagavatapurana

- Brahmandapurana

- Banerjee, Jitendra Nath, The Hindu Concept of Go , America Star Books, Maryland, 2011

- Goodall, Dominic, Parakhyatantram: A Scripture of the Saiva Siddhanta, Institute Fancis De Pondicherry, Pondicherry, 2004.

- Garudapurana

- Gobhilagrihyasutra

- Harivamsha

- Jha, CB, Ayurvediya Rasashastra, Chowkambha Prakashana, Varanasi, 2000.

- Kant, Surya, Tantrik Diksha, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1954

- Khadiragrihya

- Kumarasambhava

- Kempers, Bernet A.J, Monumental Bali: Introduction to Balinese Archaeology & Guide to the Monuments, Periplus Editions, Singapore, 1991.

- Manusmriti

- Mahabharata

- Mahamayuri Vidyarajini Sutta

- Matrudevobhava

- Meghadoot

- Muni Amar, Sachitra Tirthankar Charitra, Padma Prakashan, Delhi, 1995.

- King Shudraka, Arthur William (Tr), Mrichckatikam –Samskrit Play (The Little Clay Cart), Harvard University, Massachusetts, 1905.

- Rakshasbandhanmantra

- Sudhakar Mangalodayam, Vastubali, CICC Book House, Kerala, 2008.

- Uttarramacharitra

- Vishnusahastranamavalli

References:

[1] Atharvaveda, 2.17.3 (बलमसि बलं दाः स्वाहा ॥)

[2] Vishnusahasranamavali, 172nd name of Vishnu “Mahabalah”

[3] Fifty eighth name of Lord Krishna (Om Baline Namaha)

[4] 19th out of 100 names of Balrama

[5] (i) Williams George, Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, London, 2008 pp.73–74.

(ii) Rakshasbandhanmantra (येन बधो बली राजा दानवेंद्रो महाबल: I yena baddho balī rājā dānavendro mahābalaḥ)

(iii) Meghadoot, 59

[6] Harivamsha, v.1.31; Ch.9:Mahabharata, Adiparva

[7] Kathasaritsagara (ocean of streams of story), chapter-45.

[8] Mahamayuri Vidyarajini Sutta, 104

[9] Muni Amar, Sachitra Tirthankar Charitra, Padma Prakashan, Delhi, 1995, p.274.

[10] Goodall Dominic, Parakhyatantram: A Scripture of the Saiva Siddhanta, Institut Fancis De Pondicherry, Pondicharry, v.5.44-45, p.78

[11] Kempers Bernet A.J, Monumental Bali: Introduction to Balinese Archaeology & Guide to the Monuments, Periplus Editions, Singapore, 1991, p. 35-36.

[12] (i) Bhagavatapurana, v.1.13,40-41;

(ii)Brahmandapurana, v.2.31, 48 ;

(iii) Manusmriti 7.8;8.37 (प्राजिघाय बलिम तथा ; prajighāya baliṃ tathā)

[13] Uttarramacharitra, 1.5 (निवारबलीं विलोकायत: ; nīvārabaliṃ vilokayataḥ)

[14] Kumarasambhava, 1.6 ; Meghadoot, 57 (अव-सीतानि बलिकर्मपर्यापतानि पुष्पाणि ; ava- citāni balikarmaparyāptāni puṣpāṇi)

[15] Gobhilagrihyasutra, 3.7

[16] (i) King Shudraka, Ryder Arthur William(Tr), Mrichckatikam –Samskrit Play (The Little Clay Cart), Harvard University, Massachusetts, 1905, v.1.9, pp.6-8, (यासां बलिः सपदिमद्गृहदेहदेहलीनां हंसैः च सारस गणैश्च विलुप्तपुरव: ; yāsāṃ baliḥ sapadimadgṛhadehalīnāṃ haṃsaiś ca sārasa gaṇaiśca viluptapūrvaḥ |)

(ii) Manusmriti, 3.67.91 (भूतायज्ञ ; bhutayajn͂a);

(iii) Gobhilagrihyasutra, Khadiragrihya 1; 5; 20.

[17] Ashtanghridayasamhita, 2.33

[18] Goodall Dominic, Parakhyatantram: A Scripture of the Saiva Siddhanta, Institut Fancis De Pondicherry, Pondicharry, 2004.

[19] Jha CB, Ayurvediya Rasashastra, Chowkambha Prakashana, Varanasi, 2000.

[20]Garudapurana, Pashu Ayurveda (The worship of Sūrya (Sun), Śiva, Durgā, Śri Viṣṇu was for protection of the elephant. bali (Oblations), offerings must be given to Bhūta (five elements) and the elephant must be bathed with caturghaṭa (four pitcherfuls) of water. The diet consecrated by reciting the proper mantras shall be given to the elephant and the elephant must be smeared with holy ashes. The sacred rites act against the influences of malignant spirits and grant immunity.)

[21] Matrudevobhava is a Kerala Tantric ritual manual dealing with the worship of Goddess Bhadrakali (also known as Rurujit) along with sapta-matris or seven mothers. The text is believed to be the first Shakta worship text from Kerala. The text is a summary of Southern Brahmayāmala texts and it systematizes and organizes the Yamala cult of mothers in twenty-eight chapters.

[22] Kant Surya, Tantrik Diksha, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 35, No. ¼, 1954, pp. 10-19

[23] Sudhakar Mangalodayam, Vastubali,CICC Book House, Kerala, 2008

[24] Banerjee Jitendra Nath, The Hindu Concept of God, America Star Books, Maryland, 2011, pp.51-59

[25] Banerjee Jitendra Nath, The Hindu Concept of God, America Star Books, Maryland, 2011, pp.51-59