The decades of 2000, and 2010, stand witness to the warm embrace between Japan and India – a distance long travelled since the time when during the mid-1960s, South Asia including India, were omitted from what Japan considered as ‘Asia’. This embrace seemingly is a mirror to the regional and global geopolitics and geo-strategy at play, which have been impacted with the strategic shifts in policy thinking and approaches occurring within Asia. In the ceaseless pursuit of securing national interests set in the backdrop of the struggle for power amongst nation-states, the upbeat phase in Indo-Japanese relations is a tangible outcome stemming from commonalities of culture, shared interests and complementing ideologies that have critically shaped the course of this bilateral relationship. The India-Japan Strategic and Global Partnership has been elevated to the new Tokyo Declaration for India-Japan Special Strategic and Global Partnership, only providing more reason to evaluate the various determinants in foreign policy-making. Perhaps among these, it is individuals and personalities who could end up being most profound in terms of outcomes. Displaying a higher degree of convergence in the political, economic, and strategic realm, the strategic realities have become far more pertinent for India and Japan, given the rising centrality of the Indo-Pacific region to regional security and stability. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has discernibly hailed the Japan-India relationship as having “… the largest potential for development for any bilateral relationship anywhere in the world.”

Decrypting the Personality Factor in Foreign Policy Thinking and Formulation

The personality traits of a decision maker and the extent to which they impact upon his foreign policy choices, can be assessed from what political scientist James Barber once remarked, “Every story of decision making is really two stories: an outer one, in which a rational man calculates and, an inner one, in which an emotional man feels. The two are forever connected”.1 Foreign policy decision-making is an outcome of how individual political leaders bestowed with power perceive and analyse events and how their motivations hold a bearing upon the conclusions they ultimately arrive upon. It is often found that culture, geography, history, ideology, and self-conceptions shape the thought process of a decision maker, forming, what often is referred to as the psycho-socio milieu of decision-making.2

Differing political environments surrounding leaders give rise to variable boundaries to operate as a natural consequence. In this reference, leaders of democracies ideally reflect the attitudes and core principles of their citizens. The broader study of foreign policy always refers back to understanding the significance of policy implementation as the key emphasis, and the concurrent effect of personalities on decision-making, which at times is difficult to quantify. The interpersonal generalisation theory suggests that behavioural differences in interpersonal situations have some correlation to behavioural differences in international situations.3 Contemporary security studies remain well positioned to absorb and analyse the effects of a state’s foreign and security policy and the underlying rationales behind it. It has been observed that focusing exclusively on domestic and individual level foreign policy analyses does feature explanations of actions and decisions of individual decision-makers, and not systems.4 On many counts, systemic theorists have argued that a system is not a simplistic summation of its constituent parts alone. The overall interaction, and relations between individuals, their characteristics, capabilities, decisions, and actions, form systemic properties that seemingly, and at times overwhelmingly, influence foreign policy decision-making.

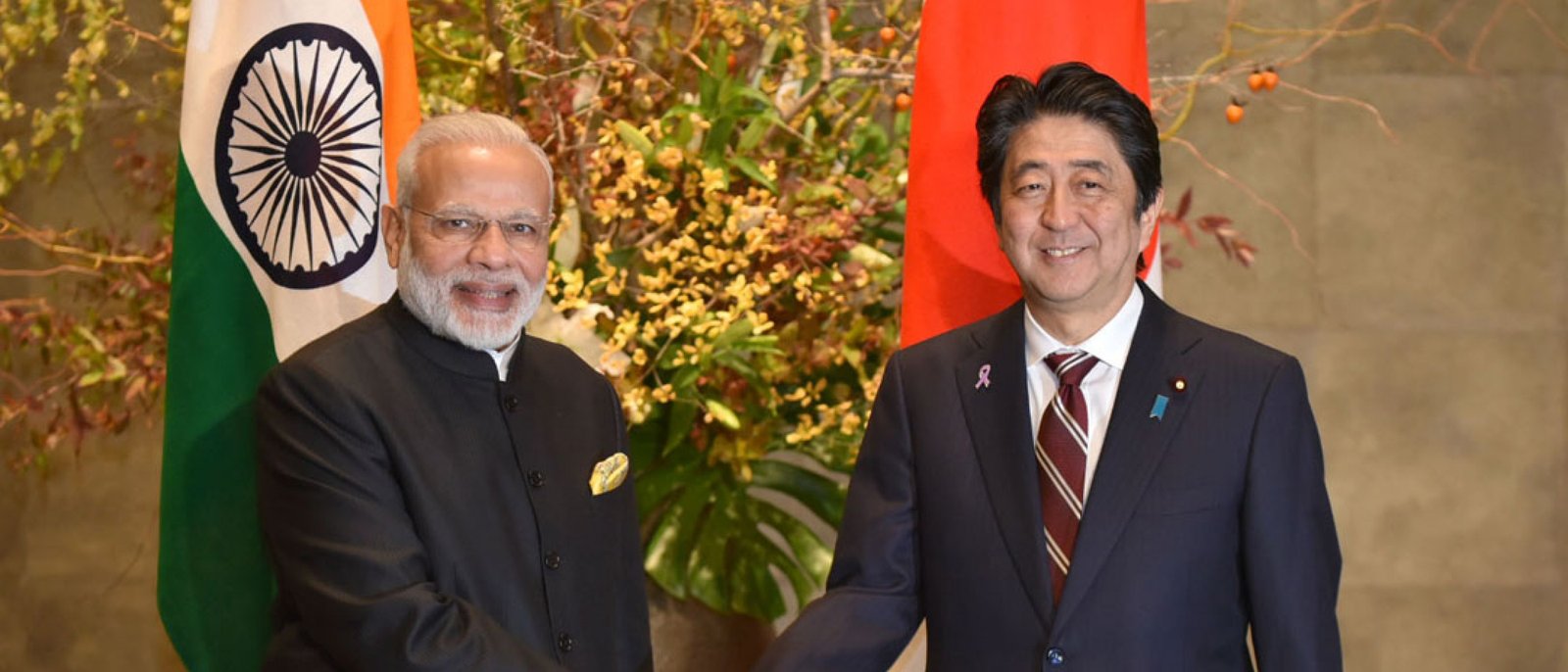

Based on the constructivist concept, wherein identity, norms, and interaction of personalities remain vital components, the equation between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe speaks volumes. The commonality of aiming towards economic development and growth that gets coupled with greater national strength and nationalism can be gauged from Abe’s idea and policy of “Japan is back” and Modi’s idea of “Shreshtha Bharat” (Superior India). The systemic conditions have presented a favourable platform for this duo to bring to light, “… the dawn of a new era in India-Japan relations”. Moreover, as PM Modi stated on an occasion, “…[The] India-Japan partnership has been fundamentally transformed and has been strengthened as a ‘special strategic and global partnership’… There are no negatives but only opportunities in this relationship which are waiting to be seized.” Providing further credence to this thought, Modi underlined the significance of India and Japan being liberal democracies, which provides them with a solid foundation to converge at various levels on the Asian stage. With a shared perspective on the future geo-political and economic order of Asia, Modi and Abe are often viewed as leaders of a new prospective dawn of an alternative regional Asian dynamic.

Personality impact in foreign policy decision-making may not necessarily be exclusive. It hinges on cognitive processes including perceptive reasoning that defines the behaviour of nation-states based upon existential constraints of the international system as well as compulsions of domestic political structures. Modi’s assurances to Japanese investors that a “red carpet” and not “red tape” would welcome them in India exhibits his intent and resolve to rewrite the rules of doing business in India. In fact, it is the flexibility in the political environs that tends to create variable boundaries in decision-making, more so, in the realm of foreign policy. The systemic conditions have presented a favourable platform for Modi and Abe to envision and operationalize what has been termed “…the dawn of a new era in India-Japan relations”.

The Trajectory of India-Japan Relations in the Modi-Abe Era

Since 2005, the Japanese and Indian Prime Ministers have held summits almost annually, with Abe and Modi specifically holding bilateral talks 11 times to date. In October 2018, Modi visited Japan for the third time and became the first foreign head of state whom Abe hosted at his holiday home in the village of Narusawa, at the foot of the scenic Mount Fuji in the Yamanashi Prefecture. The decisional latitude and output of both Modi and Abe was very much on display, and the resultant policy announcements were manifest of the same. Japan has demonstrated groundbreaking pronouncements and developments in its policy on transfer of defence equipment and technology, which can prove beneficial to India in the long run. Tokyo traditionally is known for its extremely cautious approach in this field, but the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology approved by the Abe cabinet in 2014, makes way for Japan to strengthen security and defence cooperation with its ally and strategic partners. Specifically with India, the technical discussions for future research collaboration in the areas of Unmanned Ground Vehicles and Robotics have been initiated by Japan.

The removal of six of India’s space and defence-related entities from Japan’s Foreign End User List has also been a noteworthy step. The novelty in the present setting and discussion rests in the fact that Modi and Abe have underscored distinctness in bilateral engagement between India and Japan imparted by multi-sectoral ministerial and Cabinet-level dialogues, most significantly between the Foreign Ministers, Defence Ministers and National Security Advisers. All these announcements have certainly added strategic content and furthered ties to a far more concrete level. Notwithstanding the Foreign Ministers Strategic Dialogue and Defence Ministers Dialogue, what stands out is the announcement of a “2 plus 2” dialogue, involving Foreign and Defence Secretaries, the Annual Defence Ministerial Dialogue, Defence Policy Dialogue, the National Security Advisers’ Dialogue and Staff-level Dialogue of each service.

When Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe penned his book Utsukushiikuni e (Towards a Beautiful Country) in 2006, he publicly advocated the concept of a “broader Asia” that constitutes nations in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, most significantly, campaigning in favour of strengthening ties with India. At that point, Abe appeared to have anticipated Asia’s geo-strategic future exclusively through the prism of political realism, and rightly so.5

The concept of a “broader Asia” appears to be rapidly transcending geographical boundaries, with the Pacific and Indian Oceans’ mergence becoming far more pronounced and evident than ever. In order to catch up with the reality of this “broader Asia”, Abe referred to Japan undergoing “The Discovery of India” – implying rediscovering India as a partner and a friend. The renewed focus of India’s active engagement in the region within the ambit of Modi’s “Act East” policy initiative compliments Japan’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy”. This meets dual objectives: 1) pushing Abe’s vision for an Indo-Pacific strategic framework; and 2) recognising Modi’s vision of transforming the Japan-India relationship into a partnership with great substance as a cornerstone of India’s Act East Policy.

Abe’s bid to forge this vision began in his first term as Prime Minister, when he addressed the Indian Parliament in August 2007. The most famous authored work of Mughal prince Dara Shikoh, the book Majma-ul-Bahrain (The Confluence of the Two Seas published in 1655) became the inspiration, foundation and title of Abe’s speech and vision for Indo-Japanese relations – that of nurturing an open and transparent Indo-Pacific maritime zone as part of a broader Asia.6 In fact, the “Confluence of the Two Seas” speech also underscored the pivotal advisory role of current Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary, Nobukatsu Kanehara, and special Cabinet Advisor, Tomohiko Taniguchi.

In addition to the political realities of Asia and Japan’s placement amidst it all, Abe also focused heavily on Japan’s economic health. Since coming to power in late 2012, the Abe administration unveiled a comprehensive policy package to revive the Japanese economy from nearly two decades of deflation, all while maintaining fiscal discipline. This programme came to be known as Abenomics. While it started as a stimulus measure based on three arrows, over the past few years, Abenomics has evolved into a broader blueprint for pro-growth socio-economic change that aims to lead Japan in tackling today’s challenges.7 The changes are designed to benefit all parts and facets of Japanese economy and its economic relations with major players in Asia and beyond. Setting the economy on course to overcome deflation and make a steady recovery the focus of Abenomics has been to pursue an aggressive monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy and a growth strategy that includes structural reform. Japan’s economic growth has been based on free trade, and promoting the export of Japan’s high-quality infrastructure to meet expanding global infrastructure needs.8 This initiative helps build and strengthen relationships that contribute to the economic development of partner countries.

In the above reference, the importance of securing appropriate implementation of Official Development Assistance (ODA) loan projects cannot be more emphasised, with the already received 3.5 trillion yen of public and private financing to India in five years under the “Japan-India Investment Promotion Partnership”. Japanese contributions to the development and modernisation of infrastructure in India via ODA are fast becoming a vital reference point – with a majority of ODA-related projects lying in the infrastructure sector.9 The current financial year sees commitment of a total of 390 billion yen by the Government of Japan – the highest amount committed in a single fiscal year. Incidentally, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s grandfather, former Prime Minister NobusukeKishi became the first ever Japanese Prime Minister to visit New Delhi in 1957 and launched Japan’s first post-war ODA to India.10 The journey since that time has been a long, winding one. Today, Japan’s Official Development Assistance to India is committed for an amount of Rs 14,251 crores approximately. Among other Indian states, the ODA loan includes 67.1 billion yen for the North East Road Network Connectivity Improvement Project (Phase 1).

During the successive visits of PM Modi to Japan, the synergy between India’s “Act East Policy” and Japan’s “Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure” for better regional integration and improved connectivity have repeatedly been highlighted. This policy pronouncement remains significant from India’s standpoint, especially in reference to the dire need for infrastructure build-up in India’s North-eastern states – the bridgehead of India’s connectivity to the East. Japan has pledged an ODA loan of 50 billion yen to the India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) for a public-private partnership infrastructure project in India. The ODA projects undertaken to enhance road connectivity in Northeastern India by identifying technologies, infrastructure, and strategies to facilitate development will be a critical benchmark that would test the strategic basis of India’s relationship with Japan. In this reference, Japan has agreed, in principle, to back and fund many critical Greenfield highway projects in Northeast India.11 The Japan International Cooperation Agency, which coordinates ODA for the Government of Japan will be involved in the earmarked 400 km highway stretch in Mizoram between Aizawl and Tuipang; a 150 km highway in Meghalaya; two projects in Manipur; and one each in, Tripura, Nagaland and Assam.

With the Modi government according special emphasis to the Northeast and linking it further to other economic corridors within India and Southeast Asia, Japanese cooperation for enhanced connectivity and development of this region will particularly be crucial. India and Japan need to develop a concrete roadmap for the phased transfer of technology that is in sync with the “Make in India” initiative, human resource and financial development and collaboration in highways, high speed rail technology, operations, maintenance, modernisation and expansion of the conventional railway system in India. While contribution of Japanese ODA has no doubt bridged India’s infrastructure deficit to a large extent, Tokyo’s role in developing infrastructure in India’s Northeast will be the defining turn of the real “confluence” of India’s Act East initiative with Japan’s Indo-Pacific strategy. This would be in addition to developing the bullet train, Shinkansentrunkline, between Mumbai and Ahmedabad by 2023 – a project that was adopted in 2015, giving India its first, 500-km rapid railway linking Mumbai and Ahmedabad in western India. Roughly half of the 300 billion yen in Japanese loans to India shall reportedly be utilised to fund this project.

Is the ‘Broader Asia’ Schematic Maladaptive?

The constructivist concept especially vis-à-vis interaction of personalities, is likely to become the defining factor in India-Japan relations. Since Abe and Modi share similar perspectives on Asia’s future geo-political and economic order, they should not let go of the solid foundation and converge at the strategic level for greater leverage and say in the future security design of Asia. After more than six years of negotiation Japan signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with India in 2016, paving way for the export of Japanese nuclear power plant technology to India, in addition to Modi and Abe’s call for greater cooperation to promote entrepreneurship and collaborative infrastructure development in third-party countries namely Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and others in Southeast Asia and Africa, are fine examples of their decisional latitude discussed earlier in the paper.

The time has come to make flexible, the variable boundaries in decision-making that political environs tend to create in the realm of foreign policy and achieve strategic deliverables in the coming years, without allowing any external third factor to cast a shadow on the meteoric rise in Indo-Japanese ties. Samuel Huntington famously said, “… the size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance within a few decades.”12 This argument notwithstanding, the progress in Japan-India relations in recent years has often been viewed as an effort by both countries to counter China’s expanding economic and political influence in Asia.13 Although not entirely balanced and sustainable, but often underscored, is the fact that China remains India’s and Japan’s largest trading partner individually. The power differential caused by Beijing’s growth and push outside its borders, evidenced by grand initiatives such as the Belt and Road project and strategy will be a very significant factor in determining regional geo-strategic permutations, through the strategically maladaptive China-India-Japan triangle, the outcome of which shall bear an imprint on the future security design within Asia. While economic symbiosis appears the ideal driver for states to adopt cooperative frameworks, the concurrently pressing geo-strategic realities are likely to invade upon any/all realignments in the China-India-Japan security triangle. The last meeting between Abe and Modi in October 2018 in Tokyo happened immediately following Abe’s return from his official visit to China – in what became the first trip by a Japanese Prime Minister to China in seven years, during which he expressed hopes to lift Japan-China relations into “a new era.”

Viewed from the perspective of their bilateral China policies, both countries’ policy is pressed towards engagement in economic areas and hedging in terms of security – that is often said to have drawn Japan and India closer together.14 The phrase “broad-based diplomacy in Asia” is often discussed and debated within Tokyo’s policymaking circles wherein it is argued that the major challenge for Japan-India relations going forward will be to find ways through which the two countries can elevate their ties to new stages on the basis of their latest agreements, instead of being a mere counterweight to China’s rise.15 This has been termed as a ‘challenge’ primarily owing to the following questions: First, how will Japan run this initiative alongside his administration’s recent avowed shift from “competition to collaboration” with China? And, second, the informal April 2018 Wuhan Summit saw a recommitment by India and China to ‘manage bilateral relations’ in a manner that ‘creates conditions’ for the Asian Century – a commitment that follows the formal joining of India as a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Astana in 2017.

The Modi-Abe leadership combine exhibits showmanship, content, and cognitive consistency by means of converging themes of nationalism, coupled with motivated eagerness to initiate action driven towards ushering in an era of policy-oriented change, both domestically, and regionally – an ostensibly grand enterprise which is likely to get recurrently challenged by the latest turn of events that showcase India and Japan’s critical wariness and calculus vis-à-vis China in the triangular security dynamic. Whether Tokyo and New Delhi will be able to realize the theoretical potential displayed by the personality factor of Modi and Abe shall be put on test in the coming years.

(Dr. Monika Chansoria is a Tokyo-based Senior Fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs (JIIA) since 2017. Previously, she has held appointments at the Sandia National Laboratories (U.S.), the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (Paris) and at Hokkaido University (Sapporo, Japan). Dr.Chansoria has authored five books including her latest title, ‘China, Japan, and Senkaku Islands: Conflict in the East China Sea amid an American Shadow’ (Routledge © 2018).)

References:

1 James David Barber, The Presidential Character: Predicting Performance in the White House,

2 Harold Hance Sprout, et al., The Ecological Perspective on Human Affairs, With Special Reference to International Politics, Princeton Center of International Studies, January 1965.

3 For more details see, L.S. Etheredge, “Personality Effects on American Foreign Policy, 1898-1968: A Test of Interpersonal Generalization Theory,” American Political Science Review, vol.72, no. 2, 1978.

4 Valerie M. Hudson, “Foreign Policy Analysis: Actor-Specific Theory and the Ground of International Relations,” Foreign Policy Analysis, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1–30.

5 For details, see Monika Chansoria, “Modi-Abe Personality Impacts Foreign Policy,” The Sunday Guardian, September 20, 2014.

6 Ibid.

7 “Abenomics keeps boosting Japan’s economy,” Cabinet Public Relations Office, Cabinet Secretariat, Tokyo.

8 Ibid.

9 Monika Chansoria, “Japan’s loans should focus on Northeast,” The Sunday Guardian, December 10, 2016.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 For details see, Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 72, no. 3, Summer 1993.

13 “Japan-India ties should go beyond countering China,” Editorial, The Japan Times, October 30, 2018.

14 TakenoriHorimoto, “Japan-India Rapprochement and Its Future Issues”, Toward the World’s Third Great Power: India’s Pursuit of Strategic Autonomy (Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2015) cited in Japan’s Diplomacy Series, Japan Digital Library.

15 The Japan Times, n. 13; more so, the author makes this argument based on her opinion and inferences following numerous discussions and interactions with senior officials in the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Cabinet Secretariat, Tokyo.

(This article is carried in the print edition of May-June 2019 issue of India Foundation Journal.)