Introduction: Trade Policy in the Context of the Vision for Viksit Bharat

India has set itself an ambitious target. The country hopes to transform into a developed economy with commensurate per capita income and quality of life by 2047. This vision of Viksit Bharat envisages a robust economy that is globally competitive and integrated into global value chains, generating economic opportunities for Indian workers and businesses to assist in fulfilling this transformation into a developed economy. Integral to this vision is a diversified and technologically advanced industrial sector that serves as an engine of growth and employment creation and a means to meet India’s security needs, reinforcing India’s emergence as a global power.

Achieving this goal would require sustained economic growth of at least 8% for well over a decade. However, such growth would also need to produce relatively well-paying jobs capable of absorbing the millions of working-age Indians. With around 990 million people in its working-age population, India currently boasts the world’s largest cohort of potential workers. This presents both a challenge and an opportunity. If this population is productively employed, it will create a virtuous cycle of production leading to income and demand that will aid India in achieving its target of Viksit Bharat. Generating such productive employment would necessitate a rapid expansion of the manufacturing and services sectors, allowing India to leverage demand drivers in both the domestic and global economies. Consequently, India’s trade and investment strategies are central to its path towards Viksit Bharat.

However, this growth path is complicated by the increasingly rapid adoption of automation and robotics in manufacturing, along with AI-led solutions in services. East Asian economies, including China, relied on relatively low labour costs, supported by decent infrastructure and political stability, to attract the labour-intensive segments of the manufacturing value chain to their countries during their industrial transformation from the 1980s to the early 2000s. Indian workers will now have to compete not only with workers from other countries in terms of productivity and cost, but also with robots and AI-led automation in skilled jobs.

Autor (2019) presents evidence of a highly polarised labour market due to such technological shocks, with high returns for the highly skilled and increasingly lower returns and opportunities for less skilled workers. This indicates a shrinking number of ‘middle-class’ jobs precisely when India would want millions of its low-wage workers to transition towards better-paying middle-class jobs to drive its economic development. Giuntella et al. (2022) show that China is already facing a challenge from the adoption of robotics despite the scale and depth of its manufacturing sector. The increasing use of robots to enhance productivity and reduce costs diminishes economic opportunities for less-skilled workers in China. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020) have shown that the growing use of robots reduces wages and employment, while Christiansen and Winkler (2019), using the trade flows between the US and Mexico as an example, provide evidence that increasing automation in developed country industries has reduced export opportunities for developing countries.

India would have to contend with this challenging technology transition and what many economists have termed the ‘China Shock’. China’s economy and manufacturing exports have grown at an unprecedented rate over the past three decades since the 1990s. As Table 1 below shows, China’s share of global manufacturing output increased 11.5 times from just 2.5% in 1990 to 28.7% in 2020. Currently, China accounts for close to one-third of global manufacturing output. No other single economy has dominated global manufacturing as China’s does today. China’s global share of manufacturing exports increased marginally from 1.5% to 1.8% between 1990 and 2000. However, it increased exponentially post-2000 after China became a member of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), reaching 14% by 2023.

Table 1: Share of Global Manufacturing Output

| Countries/Region | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2020 |

| China | 3.70% | 2.50% | 6.40% | 18.20% | 28.70% |

| Germany | 9.00% | 9.50% | 6.70% | 6.30% | 5.40% |

| India | 1.10% | 1.20% | 1.20% | 2.70% | 2.80% |

| Japan | 11.00% | 17.90% | 18.60% | 11.30% | 7.50% |

| Korea, Republic of | 0.50% | 1.50% | 2.50% | 3.00% | 3.00% |

| South-eastern Asia | 1.30% | 1.80% | 2.70% | 4.40% | 4.90% |

Source: Author’s calculation based on UNCTAD Data

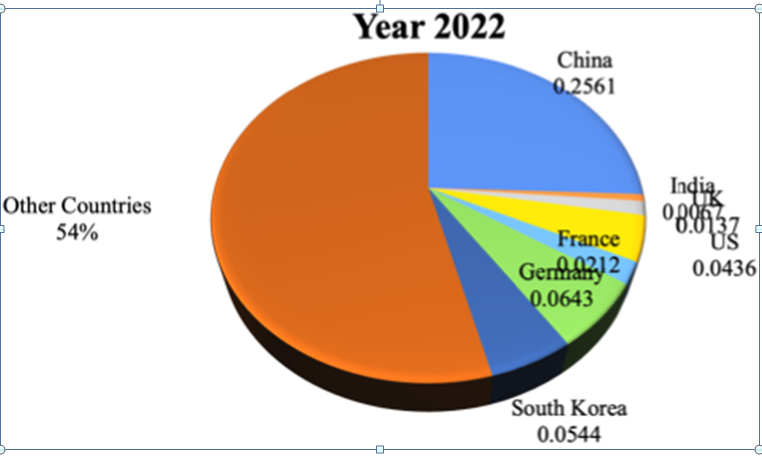

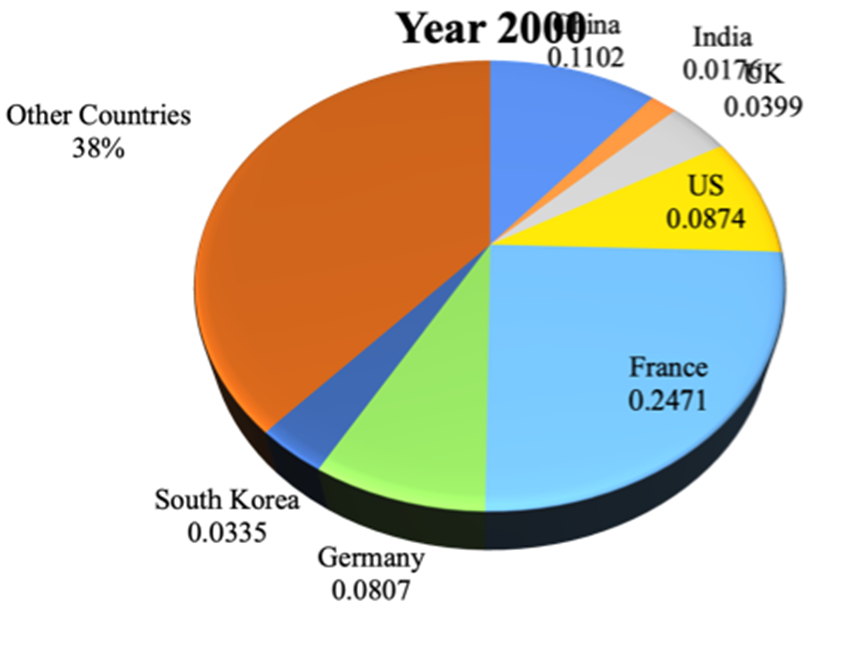

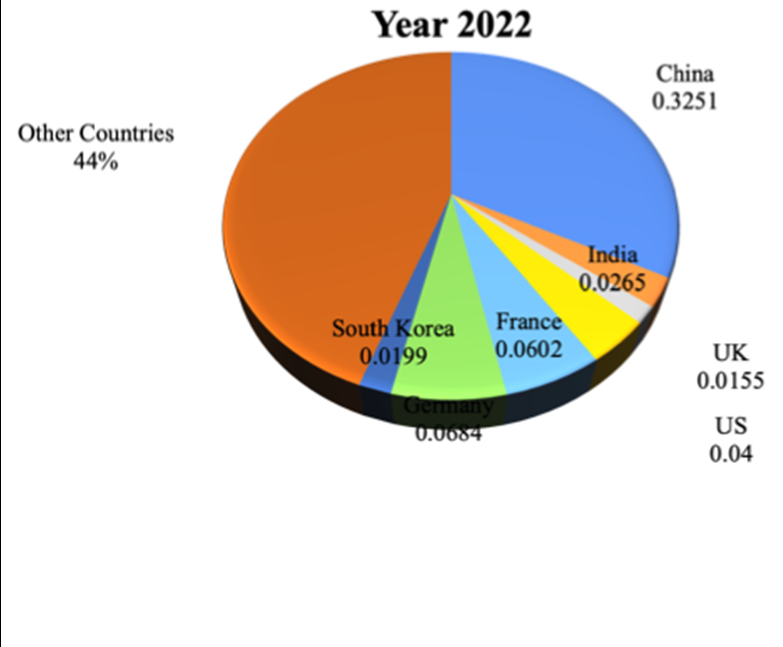

China has not only come to dominate labour-intensive manufacturing exports (global share rising from 11% to 32% between 2000 and 2022), but also high-tech manufacturing exports (global share rising from just 4.5% to 25.6% between 2000 and 2022), as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Global Share of Manufacturing Exports

High-tech Products

|

Labour Intensive Products

|

|

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS) UN COMTRADE

The impact of this rapid and unprecedented rise has been further exacerbated by the fact that China has largely followed a mercantilist approach, encouraging exports and production while limiting consumption and imports. This gap between China’s exports and imports has been widening since the early 2000s (see figure 2 below). It is important to note that China’s share of global exports has not increased since 2016 and has remained stable at around 13% to 14%. This stagnation is partially attributable to tariff protections targeting Chinese imports implemented during the first Trump administration and protectionist measures in the EU and several other Asian countries. Nevertheless, China’s share of global manufacturing output has continued to grow, supported by state assistance, thereby increasing the risk of creating global overcapacity across various sectors[1].

Source: Authors’ calculations-based World Development Indicators Database, World Bank

This unprecedented and unbalanced growth of China’s manufacturing sector and its domination of manufacturing exports have resulted in severe economic distress and job losses. Caliendo et al. (2019) and Autor et al. (2013) provide evidence of such significant job reductions due to this so-called ‘China Shock’. A Rhodium Group report from 2024 emphasises that developing countries have been particularly adversely affected by China’s mercantilist policies[2].

The western world, particularly the United States, facilitated the entry of China, a non-democratic polity and a non-market economy, into the rules-based trading architecture of the global economy as represented by the WTO in 2000, with the hope that increasing integration with the global economy and rising incomes would lead to a democratic transition. It is clear that developments in China are actually moving in the opposite direction. As long as China’s unfair trade practices predominantly affected labour-intensive industries, with the adverse effects primarily felt by developing countries like India, the Western nations (and Japan) showed little concern (Banerjee et al. 2025a). In fact, many Western economists argued that Chinese subsidies helped manage inflation in their countries and that cheaper Chinese industrial parts and components enhanced the competitiveness of Western industries[3].

However, as China began to challenge the dominance of Western economies in their core tech-intensive sectors, Western countries started to push back with more protectionist policies and state support for their own industries, often in contravention of the global rules they themselves championed a few decades ago. The tariff policies under the Trump administration and industrial policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS Act under the Biden administration are examples of such trade-distorting policies. The EU has been actively using environmental policies, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Measures or CBAM, as a guise for protectionism. This Western reaction to the global imbalance caused by China is also shrinking the global opportunities available to large developing countries like India, precisely at a time when it needs to leverage such opportunities the most.

Another major concern arising from China’s domination of global manufacturing and exports is the vulnerabilities created for global supply chains due to over-reliance on China (or any single country). China has a 65% or greater share of imports in 407 products that are critically important, as they are associated with national security, healthcare, agriculture (fertilisers), renewable energy, or represent key intermediate inputs to industry[4]. Such dependence can be easily weaponised by China, as demonstrated by the recent instance of China withholding the export of key capital machinery to slow down the shift of smartphone manufacturing to India[5], or export controls of industrial magnets[6] that have widespread industrial application including in the automobile industry, are perfect examples of such weaponisation of supply-chains.

China has also employed predatory pricing to eliminate any domestic capacity a country has, thereby increasing dependence on Chinese imports. In India, this was evident in the case of several chemicals that are Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) critical to India’s pharmaceutical industry. Consequently, reducing dependence, particularly on unreliable trade partners whose geopolitical interests do not align with India, assumes significant importance.

Indian trade and investment policy must account for and address these fundamental challenges. India needs to establish trade deals that ensure assured access to key markets and eliminate both tariff and non-tariff barriers to its exports. Such assured market access would attract FDI and enable India to leverage global opportunities to drive its economic growth. However, making such deals requires reducing its own tariff barriers. India must negotiate optimal pathways for tariff liberalisation that allow it to provide strategic short- to medium-term protection to key industrial sectors, enabling them to grow while also safeguarding vulnerable sectors of its economy. Furthermore, India must ensure that it is perceived as a trusted partner and is not denied essential technologies.

Another priority would be to address unfair trade practices, particularly those originating from non-market economies. Simultaneously, India would need to advocate for flexibilities in global rules on industrial policy, allowing it to implement strategies that foster manufacturing growth and lift the majority of its population out of poverty and into the middle class. This would require persuading its main economic partners of the necessity for such flexibilities to pursue industrial policies that are intelligent, targeted, and effective, while not being entirely consistent with WTO rules on subsidies and state support for industries.

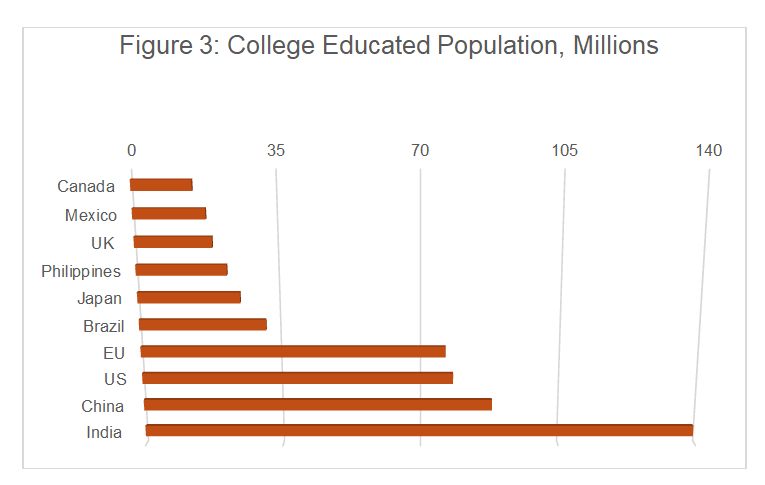

Another key policy objective would be to further enhance India’s competitive advantage in high-skilled services. Increasing digitalisation is amplifying the scale and scope of services trade. As Indian skilled workers bring an increasing level of competition to workers in developed countries across various occupations, there will be mounting pressure on the governments of those countries to protect their workers from such Indian competition. India will need to pre-empt this protectionism and ensure that the economic benefits of services trade, which could generate millions of well-paid jobs and help create an urban middle-class revolution several times the scale of that generated by IT-led development in the 2000s, are not hampered by such protectionist pressures (Banerjee et al. 2025b). As figure 3 below shows, India boasts the world’s largest cohort of college-educated individuals. Effectively leveraging this talent will be a critical aspect of India’s successful transformation into a developed economy.

Source: Global Tech Talent Guidebook 2025, CBRE Research

The following sections will discuss trade policy in relation to specific goals such as ensuring market access for Indian exports, attracting investment, and enhancing technology accessibility for Indian firms. We will also examine the role of bilateral agreements in fostering more resilient supply chains.

Trade Agreements and Market Access

Sustained growth of Indian manufacturing and services will require leveraging both domestic and global opportunities. Ensuring assured market access to the world’s major economies and growth regions is, therefore, a critical priority for Indian policymakers. India already has FTAs in place with Japan, Korea, ASEAN, the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), and the UK[7]. It is currently pursuing FTAs with nearly all the other major industrial economies, including Australia[8], the European Union (EU), and the USA[9].

Having negotiated an FTA with the UAE. India is actively considering initiating agreements with the other Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) member states, including Saudi Arabia[10]. India is engaged in discussions with Russia and other member states of the Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU) for an FTA. Additionally, India is actively pursuing negotiations with major economies in Africa and Latin America for FTAs. The overarching objective is to establish FTAS with all G20 economies, excluding China, by 2030, as well as with the key emerging regions in Africa and Latin America.

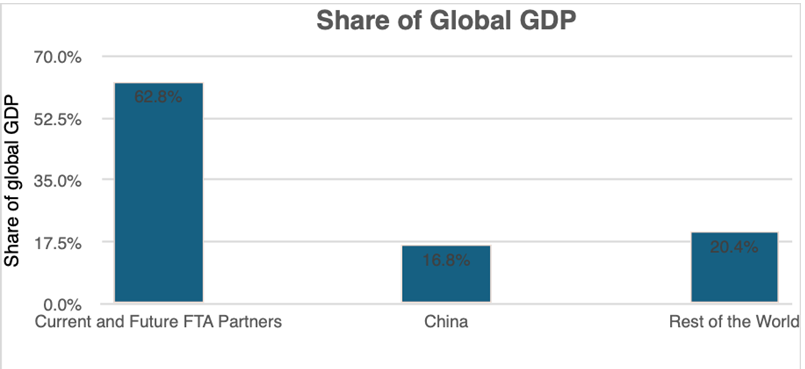

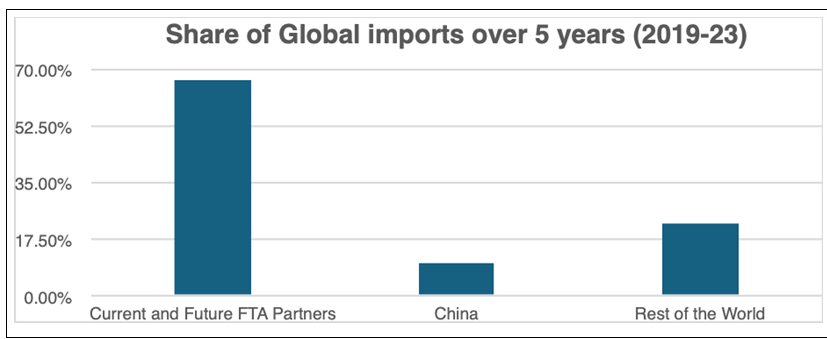

According to WTO rules, India’s so-called MFN tariffs are available to all WTO member states, including non-market trade distorters like China. Therefore, India cannot discriminate and impose higher tariffs on non-market economies while applying lower tariffs on others. However, India can offer reduced tariffs without violating WTO rules to all countries or regions with which it has negotiated an FTA. India should aim to negotiate and finalise such FTAs with all major economies and trade partners by 2030. These FTA partners would account for a significant portion of global trade covered by FTAs[11]. As Figures 4a and 4b below demonstrate, India’s FTA strategy would integrate the country with economies representing two-thirds of global GDP and more than two-thirds of global import demand. Consequently, India’s MFN tariffs would effectively apply only to China and other non-market economies with which India has not negotiated FTAs.

| Figure 4a |

|

| Figure 5a |

|

Source: Calculations based on World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS)

Strategically, this would provide India with the policy space to achieve two important objectives. First, increase such MFN tariffs as high as possible to counter non-market trade-distorting actions by non-market economies while ensuring they do not impact trade with other major market economies, which will be covered by much lower FTA tariffs. Second, use such high MFN tariffs strategically to reduce import dependence and supply-chain vulnerability, and ‘friendshore[12]’ supplies from preferred FTA partners.

India’s FTA strategy aligns completely with the vision of Atmanirbhar Bharat. Thus far, India has largely succeeded in excluding certain sectors from market liberalisation or securing considerably long transition periods before opening its markets to key strategic sectors that are integral to its long-term industrial policy strategy[13] (which we discuss subsequently). This will provide some breathing space before such sectors are exposed to foreign competition as tariffs decrease. India will need to leverage its domestic market size and enhance scale and competence in these crucial sectors that are set to dominate the global economy in the future.

Non-tariff barriers related to product standards, national security, consumer safety, health, and the environment are becoming greater obstacles to trade than tariffs. India must, therefore, ensure that these non-tariff barriers do not hinder its export opportunities. To achieve this, it needs to identify innovative provisions within its FTAs that focus on minimising the costs of complying with these standards and regulations for India’s exporters. India has been relatively less successful in this regard, making it a crucial area for further development and application as the country advances its FTA strategy.

Digitally delivered services are set to increasingly dominate the global value chain. India is the hub for Global Capability Centres (GCCs) mediating these emerging value chains. The growth of GCCs is central to fostering the next ‘middle-class’ revolution in India, creating millions of high-paying jobs in the country. India’s FTAs with key economies must include measures that pre-empt any protectionism in market access for Indian services exports. Many of these protectionist measures are currently absent, not discussed, or not applied, so there is still time for pre-emption. While India has secured some binding commitments for the cross-border digital delivery of services, this remains a work in progress, and there is a need for a more comprehensive strategy on this front[14].

Ensuring gainful employment opportunities for India’s large working-age population will require leveraging global demand for workers, particularly in countries with ageing populations where such demand is likely to emerge. Services chapters in FTAs present opportunities for India to secure binding commitments on labour mobility for skilled service workers. Moreover, India must proactively seek stand-alone bilateral mobility agreements outside of FTAs that would enable Indian industrial workers and less-skilled service workers to find employment globally.

Investment and Technology

FTAs play a crucial role in attracting investments into the country. As mentioned earlier, FTAs provide predictability concerning tariffs through binding commitments on reduced tariffs and on regulatory aspects of trade. Businesses are therefore more inclined to invest due to the reduced risk of policy-induced shocks once an FTA is established. There is robust empirical evidence linking binding tariff liberalisation and regulatory predictability in FTAs to significant increases in FDI. The impact of FTAs on boosting FDI is particularly evident in agreements between developed and developing countries (Laget et al. 2021).

India’s FTA policy has been strategised based on the FTA-FDI linkage, which is why India has prioritised its FTAs with major industrialised economies. While the FTA-FDI linkage has traditionally been implicit, India has introduced innovations in FTA disciplines to create an explicit connection. It is important to note that the India-EFTA TEPA is the world’s first FTA explicitly establishing a discipline linking market access outcomes to FDI.

The agreement acknowledges that one fundamental trade-off in FTAs with advanced countries is opening up India’s vast and growing market in exchange for access to global value chains dominated by MNCs based in these advanced economies. FDI from these global MNCs and their affiliated suppliers in India will be crucial to India’s capacity to expand manufacturing and exports. It will also be central to technology and skills transfer. The India-EFTA TEPA includes a commitment from EFTA member states led by Switzerland to invest USD 100 billion and create 1 million jobs in India within 15 years of the agreement’s entry into force. This Indian innovation is being closely examined by other large developing economies seeking to emulate it in their FTAs.

FDI relies on the ease of doing business (EoDB). India has prioritised EoDB under Prime Minister Modi’s leadership since 2014 and has made significant progress. Over 39,000 compliance requirements have been streamlined, and over 3,400 legal provisions have been decriminalised. A comprehensive programme led by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), involving both central and state governments, has been established to implement reforms. This is crucial since the vast majority of clearances and procedures investors face fall under state governments’ jurisdiction. These ongoing efforts have elevated India’s rank in the World Bank’s EoDB Report from 142nd in 2014 to 63rd in 2019[15].

India is also exploring innovations within FTAs to incorporate disciplines on investment facilitation that offer greater assurance to investors. India’s newer FTAs aim to include disciplines on good regulatory practices (GRP) that will help catalyse faster reforms within India, provide opportunities to learn from the best practices of its trade partners, and foster collaborations and capacity building in this area.

However, one area where India needs to bring greater policy focus and reform is Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs). BITs protect foreign investors from adverse policy changes or conditions. The current model of BITs that India insists on is generally considered ineffective as it does not include disciplines that would assure foreign investors. For example, it excludes taxation policies from BITs, exposing foreign investors to sudden tax policy changes without any recourse in the investment treaty. They also require investors to exhaust all domestic legal remedies for a set period (e.g., five years) before resorting to international arbitration. This can lead to significant delays and discourage investors who prefer a quicker resolution process.

As India becomes an outward foreign investor, seeking access to essential raw materials, critical technology, and infrastructure assets to support its ambition of becoming a significant player in planned global trading corridors like IMEC, its firms will also require investment protection. Therefore, India’s BITs must reflect this dual reality: Indian investment may also need safeguarding in a world characterised by policy uncertainty and shifting geopolitical concerns, where countries may be inclined to alter policies that affect investments.

Technology

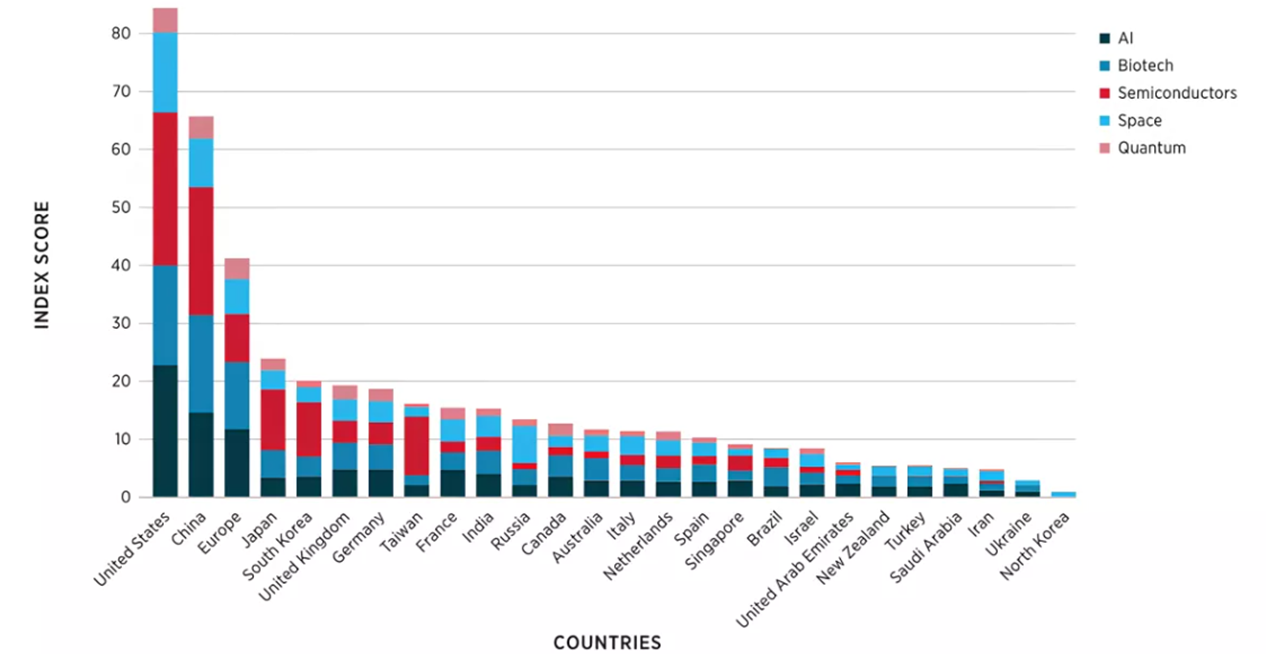

Despite rapid advancements in key areas of technology and engineering and some remarkable achievements in space, defence, biotechnology, and other fields, India has yet to catch up with its peers. In a global economy where competitiveness is defined by the ability to access, adopt, and develop cutting-edge technology, India must implement strategies that minimise impediments to the accessibility and adoptability of technology. Access to technology is critical for India’s successful integration and eventual leadership in two major transformations in the global economy: the green transition to more sustainable energy sources and the digital transition. Figure 5 illustrates India’s relative position among global tech leaders in critical technologies. India is ranked 9th overall and significantly lags in areas such as semiconductors and quantum computing.

Figure 5: India’s relative performance in key technologies among technology leaders

Source: Taken from the Emerging and Critical Technologies Index, published by the Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, June 2025

Technology denial is an inherent aspect of geopolitical tension. Technology leaders like the EU, the US, and Japan increasingly attempt to withhold technological know-how and hardware from less-trusted players. The US policy of restricting the export of high-performance AI chips to only a few trusted countries is but one example of such emerging challenges.

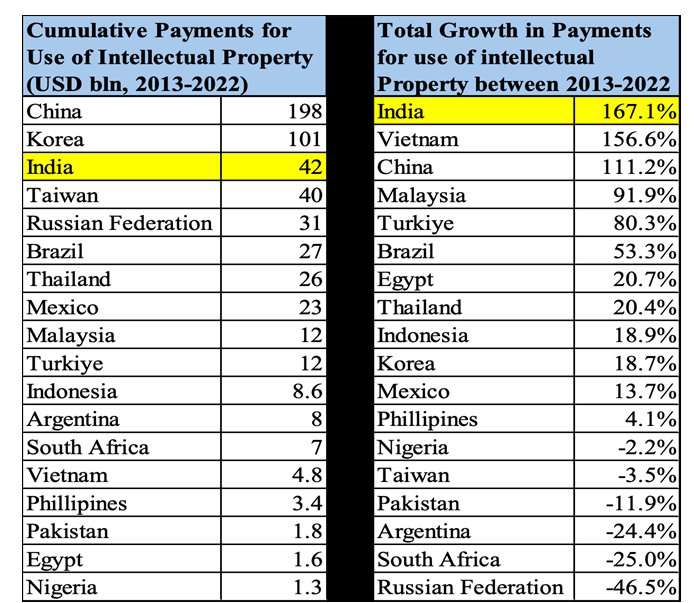

India’s independent courts and rule of law, which prevent technology theft and hold violators accountable, provide the foundation on which India could be regarded as a trusted partner for technology transfer by Western firms and countries. As FTAs enhance trade and investment linkages between India and industrialised economies, Western multinational technology leaders would have a significant incentive to engage in technology transfer and cooperation with India. As Table 2 illustrates, India ranks third among large developing and newly industrialised economies as a technology market and is the fastest-growing one.

Table 2: India as a market for technology: Relative importance among developing countries and NIE peers

Source: Calculations using the Trade in Services by Mode of Supply (TISMOS) database, WTO

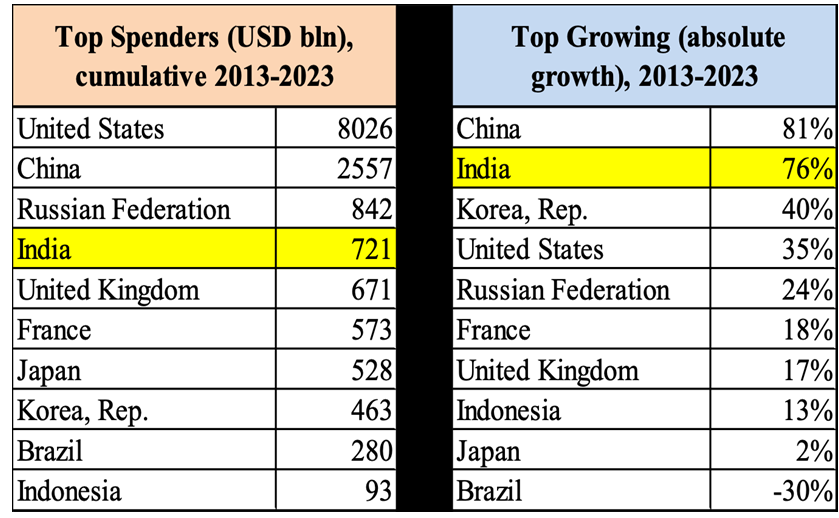

India’s vast pool of highly skilled labour (see Figure 2) offers another key advantage in joint technology development and innovation. India has emerged as one of the largest defence procurers in the world. It has successfully leveraged its purchasing power to advocate for licensed production, joint product development, and technology partnerships. The recent successes in indigenous production and development are attributed to reforms in the procurement process and strategy involving the Indian private sector.

Military technologies have significant spillovers for non-military commercial applications. The US military-industrial complex is a prime example of cutting-edge commercial product development. From Ray-Ban sunglasses to the internet, the defence sector has been the source of some of the most successful commercial products. A strategic approach to India’s defence procurement, as it expands in scale and scope to facilitate technology transfer, is critical to India’s long-term trade and industrialisation policies. As Figure 3 illustrates, India is the world’s fourth-largest defence spender, and its spending growth is second only to China among the leading countries.

Table 3: India as a defence spender: Relative importance among leading economies

Source: Calculations using World Bank Development Indicators Database

However, defence is not the only area where India’s influence in government procurement is rapidly increasing. Indian government investment and procurement in renewables, telecommunications, transport, agriculture, and medicine should be effectively leveraged along the same lines as defence. Unlike in the case of defence, procurement in these other sectors is distributed across numerous departments and state governments. This dilutes the advantage of scale. A thought-out planning process is needed where procurement remains independent, yet is conducted in a coordinated manner to capitalise on scale advantages as an incentive for technology transfer and joint development in partnership with the Indian private sector.

Finally, as will be discussed later under industrial policy, India would need to engage actively in its multilateral trade strategy within the WTO to seek flexibilities in current WTO rules[16] to use performance requirements related to investment that is trying to cash in on India’s large and growing market size. Such performance requirements may encompass technology transfer, training, or local sourcing (which facilitates tech transfer to local firms). For instance, a foreign firm keen on obtaining a share of India’s USD 10 billion per year industrial wastewater treatment market could be subjected to technology transfer and local content requirements to enhance India’s domestic capabilities in this vital area.

Developing Resilient Supply Chains

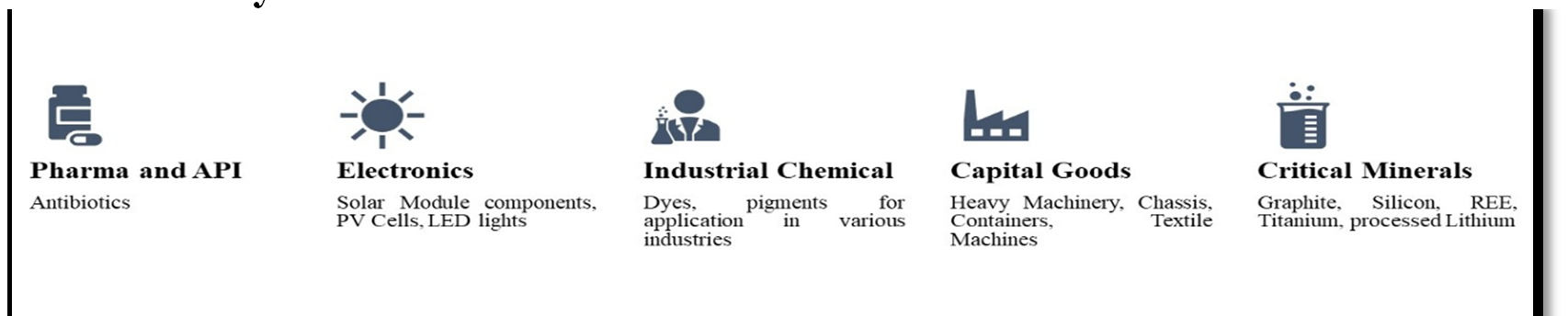

India depends significantly on foreign suppliers for critical goods and raw materials, including reliance on a single import source. In many instances, this singular source of imports is China, making India vulnerable to the potential weaponisation of supply chains. Figure 6 illustrates key areas of vulnerability for India.

Figure 6: Key Sectors and Associated Products of Supply-Chain Vulnerability for India

Source: Internal, unpublished analysis by the author

FTAs include disciplines that impose binding restrictions on partners, preventing export controls; that is, they reduce the risk of weaponisation of import dependencies. However, India has been reluctant to pursue deep commitments related to export controls due to its need to restrict exports of predominantly agricultural products to ensure food security and domestic price stability. Furthermore, India’s FTA strategy excludes China as a partner, even though dependencies on China define the majority of India’s supply-chain vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, India would benefit from reconsidering its soft commitments strategy to export controls with other trade partners, as such provisions are an essential mechanism for de-risking the supply chain. It should also be noted that WTO rules broadly prohibit export bans and restrictions, allowing members to apply them temporarily to prevent or alleviate critical shortages of foodstuffs or other essential products. However, WTO rules have been largely ineffective in preventing member states from restricting exports of various products.

India has also entered into agreements specific to supply chain security. These include the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) Supply Chain Agreement, which focuses on cooperation, information sharing, and joint crisis response mechanisms to minimise the impact of disruptions and enhance supply chain efficiency. India is also a signatory to the Mineral Security Partnership (MSP). The objective of the MSP is to coordinate policies among members to ensure effective access to critical minerals and collaborate to reduce dependencies on China overall.

India is also seeking to establish disciplines in its FTAs with countries that possess significant reserves of key natural resources, such as critical minerals, which will assist India in securing access to these resources. Examples of this strategy include discussions with Australia and Chile.

Indian policymakers are cognisant of the impact of disruptions at logistical chokepoints such as the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden. India has been focusing on creating alternative multi-modal linkages to supplement the routes where such chokepoints are situated. These initiatives include the International North-South Corridor (INSTC), linking India with Central Asia, Russia, and Europe, as well as the India-Middle-East-Europe Corridor (IMEC), which provides an alternative connection between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, bypassing the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden. Additionally, the trilateral highway offers overland connectivity between India, Southeast Asia, and the South China Sea. Unfortunately, these initiatives are progressing slowly due to geopolitical tensions and other operational challenges. Nonetheless, they remain essential objectives for India’s long-term supply chain resilience.

Last but not least, India must expand its domestic capabilities in key industries that are essential for national security, food security, and economic security. Industrial policy aimed at developing and enhancing indigenous capacity is crucial to this goal, and the next section discusses some pertinent issues regarding that topic.

Industrial Policy

India is increasingly caught between the aggressive use of state-led non-market unfair practices of the world’s largest industrial economy—China—and the well-funded industrial policies of advanced industrialised economies. Between them, these actors are attempting to squeeze out the competition in key sectors that will define the future of the global economy. India’s overall share in global manufacturing is a mere 2.9%, and in global manufacturing exports, it stands at 2.2%. Its share in high-tech sectors is just 2.7%. India must implement policies to support industrial development and competitiveness in these crucial sectors to catch up with dominant players. Since many of these policies could potentially conflict with WTO rules, for example, the performance requirements on foreign investment to aid technology transfer mentioned earlier, or subsidising inputs or credit for private industry, India would need to seek temporary flexibilities from such rules, arguing its developmental needs.

India must also find ways to discipline and limit unfair industrial policy actions that increase global developmental inequities and create global imbalances. This would entail countering China’s non-market unfair practices and finding ways to curtail aggressive and excessive industrial policies in the advanced industrial economies.

Achieving the above would necessitate independently pursuing each of the three objectives across different platforms with various sets of allies:

- Pursuing flexibilities in global rules to create policy space for India’s industrial policy: India must ally with major developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, whose interests align. The group of African nations has already submitted proposals seeking similar solutions at the WTO. With the forthcoming WTO 14th Ministerial Conference, India would benefit from articulating a position that distinguishes the legitimate developmental aims of industrial policy in most developing countries from the predatory and mercantilist industrial policies found in non-market economies like China.

- Pursue reforms in WTO rules that check unfair trade and industrial policies in non-market economies and hold them accountable: India’s interests broadly align with those of the US, EU, and Japan in this objective. India would benefit from making common cause with these developed economies and seeking to include as many developing countries as possible, which are also suffering from such unfair practices, in an alliance. In fact, the US, EU, and Japan might be willing to agree to allow market-oriented developing countries to pursue legitimate development goals with much greater freedom in using subsidies and state support in exchange for assistance in developing international disciplines to hold non-market economies accountable for their policies.

- Ensure that developed economies are held accountable for their trade-distorting policies: India must define parameters of development (per capita income, absolute number of poor people), along with the extent of global economic capabilities that prevent already prosperous countries, which have dominant industrial sectors, from using subsidies and state support that undermine competition and lead to the domination of industrial sectors by global oligopolies.

Conclusion

India’s goal of Viksit Bharat will need to be achieved under far more challenging circumstances than those faced by countries like Japan, Korea, or China during their respective transitions. The world is experiencing a backlash against globalisation and open markets, geopolitical tensions are disrupting supply chains, and access to key technologies is becoming increasingly restricted for geostrategic reasons. The relatively open markets and globalising trends that had progressed from the twentieth century into the first decade of the 21st century are now being reversed.

Furthermore, technological shocks stemming from advancements such as automation and AI have significantly diminished the creation of new jobs linked to economic growth, making it increasingly easier and cheaper to replace human workers with machines. This reduction in space for ‘labour-intensive’ economic activities poses a considerable challenge for India, which must ensure productive engagement for the world’s largest working-age population.

Adding to all this complexity is the challenge of imbalance in the global economy due to a huge non-market economy that has not played by the international rules governing trade and has weaponised both access to its market and its sheer dominance of supply chains against its competitors.

Finding comprehensive solutions that help India meet its developmental objectives by using access to global markets for goods, services, and human resources will require a focused approach involving deeper bilateral integration with major economies and regions through FTAs. Such FTAs must be complemented by matching initiatives that attract foreign investment and ensure accessibility to key technologies. India must form effective alliances to tackle the challenge of supply-chain vulnerability and the weaponisation of over-dependence on a single trade partner.

All of this would require agility. India would often find itself allied with countries in opposing geopolitical camps as it pursues its priorities in the areas mentioned above. Balancing such complexities would demand finesse and a relentless pursuit of Indian interests. More importantly, it would necessitate consistency and continuity in Indian policies over this extended period.

Author Brief Bio: Dr. Pritam Banerjee is Professor & Head, Centre for WTO Studies, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade, New Delhi.

References

Autor, David (2019) Work of the Past, Work of the Future, Working Paper No. 25588, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68.

Acemoglu, D., Restrepo, P., 2020. Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labour markets. Journal of Political Economy 128, 2188-2244.

Artuc, E, Christiaensen, L, Winkler, H. (2019) Does automation in rich countries hurt developing ones? Evidence from the us and Mexico. Evidence from the US And Mexico (February 14, 2019). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8741

Bai, Liang and Sebastian Stumpner. 2019, “Estimating US Consumer Gains from Chinese Imports.” American Economic Review: Insights, 1 (2): 209–24

Banerjee, P, Hussain, Z, and Karwal, K. (2025a) Navigating the Development Divide: The Case for Policy Space in India’s Industrial Policy Strategy Amid Rising Global Protectionism, Centre for Research in International Trade (CRIT) Working Paper No. 85

Banerjee, P, Vartul, Mandal, S, and Dua, D. (2025b) Negotiating for Digitally Delivered Services- Framework for a Comprehensive Approach, Centre for Research in International Trade (CRIT) Working Paper No. 82

Boullenois, C, and Jordan, J.A. (2024) How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies’, Rhodium Group, June

Caliendo et al. (2019) ‘Trade and Labor Market Dynamics: General Equilibrium Analysis of the China Trade Shock’, Econometrica, 87(3),

Guintella, O, Yi, L, and Wang, T (2022) How Do Workers and Households Adjust to Robots? Evidence from China, Working Paper No. 30707, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)

Jaravel, X and E Sager (2019), ‘What are the Price Effects of Trade? Evidence from the U.S. and Implications for Quantitative Trade Models’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13902 and

Laget, E, Rocha, N, and Varela, G. (2021) Deep Trade Agreement and Foreign Direct Investments, World Bank Policy Research Paper No. 9829

Endnotes

[1] Chinese state control of Banking and other investment agencies de-links investment decisions from market risks, and thereby expansion of capacities are not based on market based, risk informed decisions which would have otherwise prevented such investments

[2] How China’s Overcapacity Holds Back Emerging Economies’, Rhodium Group, June 2024

[3] Examples include Jaravel, X and E Sager (2019), ‘What are the Price Effects of Trade? Evidence from the U.S. and Implications for Quantitative Trade Models’, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13902 and Bai, Liang and Sebastian Stumpner. 2019, “Estimating US Consumer Gains from Chinese Imports.” American Economic Review: Insights, 1 (2): 209–24.

[4] Based on unpublished empirical research carried out by the author

[5] See China’s export ban on engineers and equipment disrupts manufacturing overseas, Strait Times, Published Jan 20, 2025, Singapore

[6] See China’s rare-earth curbs hit Indian auto industry, India Today, June 16th, 2025

[7] India-UK FTA was finalised in May 2025 and is expected to come into force in early 2026

[8] India has completed an early-harvest agreement with Australia and is currently negotiating to complete the comprehensive deal

[9] India is currently pursuing a Bilateral Trade Agreement with the US

[10] India has on-going negotiations with Oman

[11] India’s neighbours are already covered by South Asia Free Trade Agreement or SAFTA

[12] Friendshoring refers to the practice of developing more resilient supply-chains by sourcing imports from countries that are more dependable, politically aligned and generally considered to be market oriented and rules based.

[13] These sectors typically have the maximum potential for future growth includes electronics, advanced engineering, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, precision engineering included robotics, renewable energy etc

[14] For a more detailed discussion, see Banerjee et al 2025b

[15] The Make in India Ease of Doing Business page provides a complete list (refer to: https://www.makeinindia.com/eodb#:~:text=India%20jumps%2079%20positions%20from,of%20Doing%20Business%20Ranking%202020′.&text=To%20further%20enhance%20the%20ease,legal%20provisions%20have%20been%20decriminalized)

[16] Under the WTO agreement on Trade Related Investment Measures or TRIMS