India faces a complex and often challenging landscape in its immediate neighbourhood, shaped by a mixture of historical, geopolitical, economic, and internal factors. This article explores the various dimensions of India’s relationship with the Maldives, including maritime security, economic ties, and its diplomatic reset, placing it within the broader context of Indian Ocean geopolitics and economic cooperation.

Introduction

The Maldives, located at a strategic point in the Indian Ocean, has traditionally maintained close relations with India, based on geographic proximity, cultural links, and development cooperation. However, in recent years, the Maldives has increasingly engaged with China, attracted by large-scale infrastructure investments under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and promises of economic growth. This shift has introduced new dynamics into India–Maldives relations, as China’s expanding presence in the Maldives brings significant strategic implications for the balance of power in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). As the Maldives navigates a path between its traditional partnership with India and growing ties with China, India faces the challenge of balancing strategic assertiveness with diplomatic subtlety.

For India, maintaining influence while avoiding resentment requires a careful balance of soft power, economic outreach, and strategic vision – ensuring this remains one of the region’s most closely observed bilateral relationships. In this context, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the Maldives in July 2025, at the invitation of Maldivian President Mohamed Muizzu, marks an important step in strengthening bilateral ties between the two nations. Currently, the future of India-Maldives relations is likely to involve a mix of rivalry and collaboration due to the fluid political dynamics within the Maldives.

Geography of the Indian Ocean Region

The IOR is a maritime crossroads of global trade and geopolitics, shaped by its vast geography, diverse nations around it, strategic waterways, and abundant resources. Understanding its geography is essential for assessing the strategic calculus of regional and global powers, and the island nations, especially in the 21st century’s shifting maritime order.

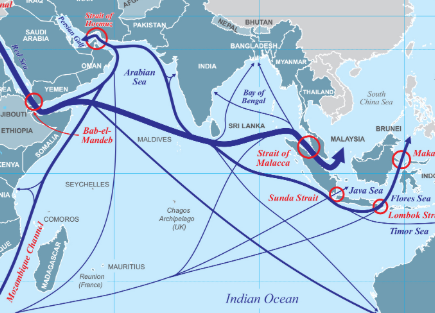

The IOR, which is the western part of the Indo-Pacific Region, is the third-largest oceanic region in the world, covering around 70 million sq km. It extends from the eastern coast of Africa to the western shores of Australia. The region is home to thirty-three nations and nearly three billion people. Major sub-regions in the IOR include the Arabian Sea, bordered by India, Pakistan, Oman, and Yemen; the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, which connect the IOR to the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal; the Bay of Bengal, surrounded by India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar; and the Andaman Sea and Malacca Strait, which are on the crucial link between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The Mozambique Channel lies between Madagascar and mainland Africa.[2]

The IOR also includes some of the world’s most critical maritime choke points. The Strait of Hormuz, situated between Oman and Iran, serves as a gateway for Persian Gulf oil. The Bab-el-Mandeb, located between Djibouti and Yemen, connects the Red Sea to the Arabian Sea. The Strait of Malacca, lying between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, is the busiest shipping lane between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, with the Sunda and Lombok Straits acting as alternative routes south of the Malacca Strait.[3]

Within its expanse lie several key island nations and territories – the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Seychelles, Mauritius, Madagascar, and Comoros – which hold considerable strategic value. Besides these, the strategic island territories in the IOR include the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India, Diego Garcia – a UK/US military base, and French territories such as Réunion and Mayotte. The region contains vital Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) used for energy and trade between the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. It is abundant in marine resources, fisheries, hydrocarbons, and undersea minerals.[4]

Approximately 80 per cent of the world’s seaborne oil trade passes through the choke points of the Indian Ocean, making it a crucial connector between the East and the West. As a result, the region has become a key geostrategic arena in the modern international system. The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has evolved into a battlefield of growing strategic rivalry among major powers—including India, China, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Its position at the centre of global maritime trade and geopolitics makes its island nations and territories strategically vital.

In today’s contested IOR and the wider Indo-Pacific, island states have increased their strategic importance by leveraging their geographic location and resources to promote national interests. It exemplifies how these island nations can strengthen their presence and assert themselves by engaging with regional powers on transactional terms. Situated at the crossroads of these key Indian Ocean trade routes, the Maldives holds significant strategic value in the IOR, acting as a crucial player in balancing the competing interests and influence of global powers.

Indian Strategy in the IOR

India’s overarching strategy in the IOR is driven by the need to ensure maritime security and freedom of navigation, safeguard SLOCs that are vital for trade and energy imports, counter China’s expanding naval presence, promote regional stability and economic growth, and reinforce its role as a net security provider in the Indian Ocean. Its broader foreign policy approach in the IOR reflects a careful balance of hard and soft power. It highlights India’s efforts to position itself as a counterbalance to China through development aid and security cooperation.[5]

India launched the SAGAR Doctrine (Security and Growth for All in the Region) in 2015 and the Neighbourhood First and MAHASAGAR (Mutual and Holistic Advancement for Security and Growth Across Regions) initiatives in 2025 with the aim of promoting collective security, enhancing capacity-building for littoral states, and encouraging economic and environmental cooperation. It also introduced the Neighbourhood First Policy, emphasising strong bilateral relations with the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Seychelles, and others, while providing development assistance, capacity-building, and infrastructure projects.

India has transformed its Look East policy into the Act East Policy to strengthen maritime engagement with ASEAN nations and promote a free, open Indo-Pacific.[6] Its Indo-Pacific Strategy supports a Free, Open, and Inclusive region in partnership with like-minded nations, notably the Quad (India, the U.S., Japan, and Australia). As a rapidly growing economic power, India is projecting its military and maritime influence by modernising its naval forces and utilising its island territories for extended regional reach.[7] To enhance Maritime Domain Awareness, it has established the Information Fusion Centre for real-time surveillance, integrated coastal radar networks with friendly IOR states, and built strategic partnerships across the IOR and Indo-Pacific.[8]

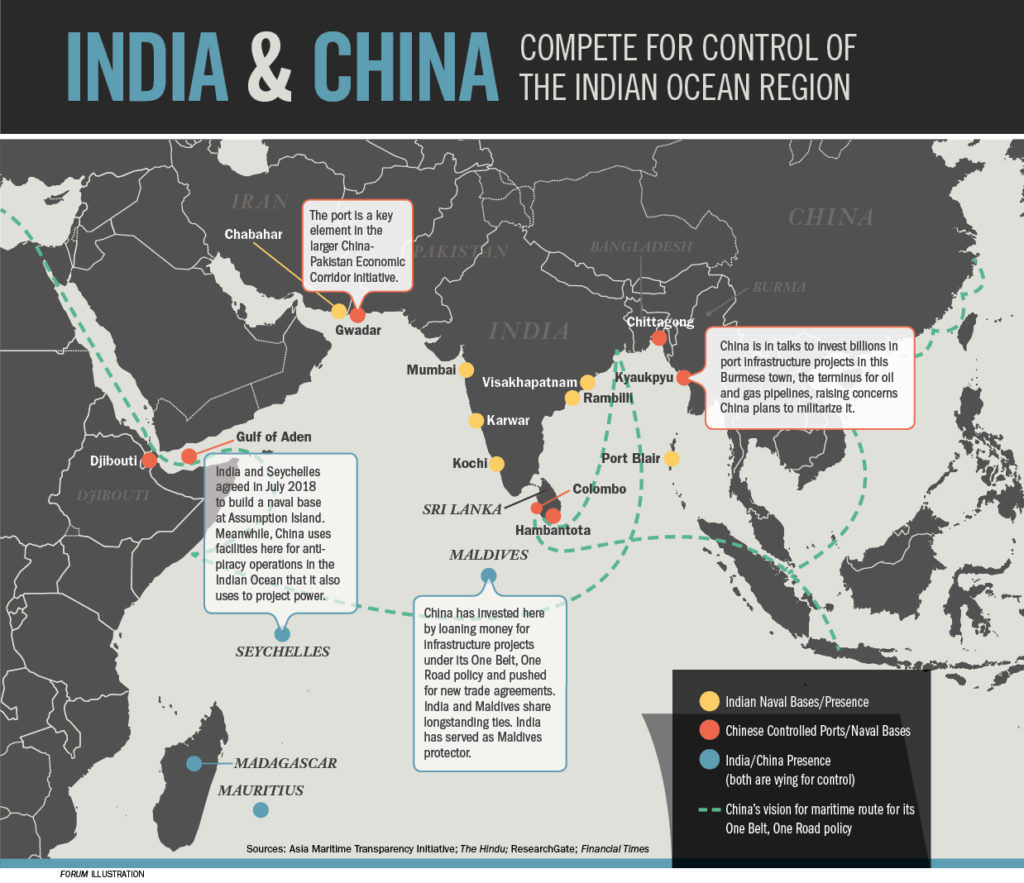

While India remains a natural leader in the Indian Ocean, it faces a complex web of strategic, diplomatic, and environmental challenges. China’s expanding presence through funded ports and infrastructure across the IOR, combined with its increasing naval patrols, submarine deployments, and debt-trap diplomacy, diminishes India’s influence in smaller IOR nations like the Maldives and Sri Lanka. Extra-regional powers such as the U.S., France, the UK, Japan, and Australia are also boosting their military and diplomatic engagement in the IOR. Although some are partners strategically, they also compete for influence, particularly in African littorals and island nations.[9]

India’s approach in the IOR combines hard power, soft power, and regional diplomacy. It aims to sustain influence by being a reliable partner, enhancing maritime capabilities, and promoting a rules-based, multipolar maritime order.

Maldives in the IOR

The Maldives is an archipelagic nation comprising 26 atolls and over 1,200 coral islands, spanning more than 750 km in the central Indian Ocean. This gives it an EEZ of approximately 900,000 km², abundant in marine biodiversity and economic opportunities. Renowned for its white-sand beaches, turquoise waters, and diverse marine life, it is one of the most geographically dispersed countries in the world. With none of its coral islands rising more than 1.8 metres above sea level, the nation is highly vulnerable to even minor sea-level rises caused by global warming. Its economy relies heavily on tourism, fisheries, and related services, with luxury tourism being a major source of revenue. Politically, the Maldives transitioned to a multi-party democracy in 2008 after decades of single-party rule under President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom. Since then, the country’s politics have seen frequent shifts in power, polarised party competition, and occasional instability, influenced by both internal and external geopolitical factors. Mohamed Muizzu was elected president in September 2023, defeating incumbent Ibrahim Mohamed Solih. He is considered a supporter of China’s interests in the country.[10]

Strategically situated along key global shipping lanes, especially the Eight Degree Channel, which is vital for maritime trade and energy routes connecting the Middle East and East Asia, the Maldives holds significant geopolitical importance and drawing the attention of major powers such as India and China. Located just 700 km southwest of India, the Maldives is strategically positioned between India’s Lakshadweep Islands and the Horn of Africa, making it a central hub in the IOR.[11]

The Maldives derives its strategic importance from its location near key SLOCs and its proximity to vital chokepoints, enabling the monitoring of maritime traffic between the Strait of Hormuz, the Strait of Malacca, and Bab-el-Mandeb. This positioning allows it to serve as a hub for naval surveillance and anti-piracy operations in the central Indian Ocean, as well as an air and naval logistics node supporting regional navies such as those of India, the U.S., and China. Its unique geography has also made the Maldives a potential buffer state between competing regional and global powers.[12]

India-Maldives Relations

The geographical proximity has fostered centuries-old cultural, economic, and people-to-people exchanges between India and the Maldives. Shared maritime traditions, linguistic similarities, and religious ties have laid the groundwork for mutual understanding. India was among the first countries to recognise the Maldives’ independence in 1965. Formal diplomatic relations were established in 1965, shortly after the Maldives separated from British protectorate status.[14]

India-Maldives relations have been strong for decades, characterised by thriving economic and security cooperation. Thousands of Maldivians have studied in India and visited the country for medical treatment. A pivotal moment occurred in 1988 during ‘Operation Cactus’, when India swiftly intervened within hours to prevent a coup attempt against President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, led by mercenaries. This gained India significant political goodwill and cemented its reputation as a reliable security partner.[15]

India has consistently been the first responder during crises — whether the 2004 tsunami, the water shortage in 2014, or the COVID-19 pandemic. It has assisted the Maldives in areas such as defence training, coastal surveillance, hydrography, and joint military exercises. Economic relations between India and the Maldives encompass sectors like trade, investment, and developmental aid. India remains a dependable partner in the Maldives’ human resource development, infrastructure, healthcare, and education sectors. Indian grants and Lines of Credit have financed vital projects, including the Indira Gandhi Memorial Hospital (IGMH) in Male, the Faculty of Engineering Technology, and the Greater Male Connectivity Project (GMCP) – India’s largest infrastructure initiative in a neighbouring country.[16]

The rise of China’s influence in the Maldives, especially under President Abdulla Yameen (2013–2018), caused a temporary strain in India-Maldives relations. Maldives joined China’s BRI and took on significant Chinese debt. However, relations with India improved under President Ibrahim Solih (2018–2023), who adopted an “India First” policy and revived strategic cooperation. This trusted relationship, however, again faced strain when President Mohamed Muizzu took office in November 2023, riding on his ‘India Out’ campaign and calling for the withdrawal of Indian military personnel from Maldivian soil. Nearly two months later, he reiterated this demand, stating that the Maldives must ensure no foreign military is present on its territory. His request for India to withdraw armed forces personnel—who had been providing search-and-rescue support to Maldivian aircraft—not only signalled a reevaluation of policy towards India but also marked a clear shift towards, and outreach to, China.[17]

The diplomatic row was worsened by derogatory comments made by three Maldivian ministers about India and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It sparked exchanges on social media, a boycott of Maldivian tourism, and increased promotion of Lakshadweep as a tourist destination, leading to a significant decline in Indian tourism, which is vital for the archipelago’s economy.[18]

Tourism is the Maldives’ largest industry, accounting for 28 percent of its GDP and over 60 percent of its foreign exchange earnings. According to recent data released by the Maldivian tourism ministry, of the 1.8 million foreign tourists who visited the Maldives in 2023, 11.2 percent were from India, followed closely by Russia (11.1 percent) and China (10 percent).[19] Adding salt to India’s wounds, Muizzu headed to China even as the row over the disparaging remarks raged on social media. He asked the Chinese to increase tourist numbers to the Maldives. Several investment and other deals were signed during this visit to China. This incident highlighted the fragility of bilateral relations and the impact of domestic political rhetoric on foreign policy.

China has been expanding its influence in the Maldives through infrastructure investments under the BRI. Its investments in the Maldives, including the $200 million China-Maldives Friendship Bridge, housing projects, airports, and maritime infrastructure, have increased economic dependencies, with Chinese loans making up nearly 40% of the Maldives’ external debt by 2023.[20] China became the Maldives’ largest trading partner and a major creditor, raising fears of debt-trap diplomacy. The strategic motivations behind China’s engagement with the Maldives can be summarised as the need for geopolitical positioning, protecting critical SLOCs through which China’s energy supplies pass, continuing the strategy of encircling India via a network of ports and bases in the IOR, using port visits and infrastructure investment to increase its presence and reach in the region until the establishment of proper dual-use facilities, and undermining Indian influence.

However, ultimately considering the strong reaction from India and its economic consequences, President Muizzu suspended the Maldivian ministers and issued a statement distancing his government from their comments, emphasising the importance of maintaining ties with India. This shift from an overtly anti-India stance to a more balanced approach by President Muizzu stemmed from both domestic and geopolitical realities. While his initial posture catered to nationalist sentiments and electoral promises, the Maldives’ heavy economic dependence on Indian tourism, development aid, and emergency assistance made prolonged hostility costly. Additionally, rising regional competition with China and the increasing strategic importance of the Indian Ocean compelled Muizzu to recalibrate, recognising that maintaining workable ties with India was essential for economic stability, security cooperation, and preserving the Maldives’ leverage in balancing major powers.

As far as India is concerned, despite tensions and the Maldives’ tilt towards China, India continued its developmental assistance, humanitarian aid, and security cooperation, underscoring its commitment to long-term partnership and regional stability. The underlying strategic logic being that sustained engagement, even during periods of strain, preserves India’s influence, counters rival presence, and reinforces its image as a reliable and indispensable partner in the IOR. While periodic political shifts create challenges, the depth of bilateral engagement, strategic alignment in the IOR, and people-to-people ties ensure the relationship remains fundamentally strong and enduring in counter-terrorism.

China Factor: Implications for India

The Chinese forays into the Maldives and other island nations such as Sri Lanka, Seychelles, and Mauritius, among others, in the Indian Ocean Region carry significant geopolitical, economic, and security implications, especially for India and other regional powers. China aims to reshape the region’s strategic environment by expanding its footprint—particularly through economic and political influence. This strategy has far-reaching strategic, economic, and security implications. It aligns with China’s broader vision of building a chain of ports and bases from the South China Sea to the Horn of Africa, enabling it to monitor key shipping lanes and improve PLA Navy (PLAN) access to critical sea routes and chokepoints. Its activities in the Maldives are therefore not isolated incidents, but part of a larger strategic agenda to expand China’s influence and secure vital footholds across the Indian Ocean Region. This necessitates ongoing vigilance, proactive diplomacy, and strong regional cooperation to safeguard freedom of navigation, defend sovereignty, and maintain stability in the Indian Ocean Region.[21]

For decades, India has been regarded as the main security provider in the Indian Ocean Region, responding promptly in times of need and working closely with island nations, including the Maldives, to support their development and safeguard their security. However, the growing influence of China and the Maldives’ shift towards it pose a significant concern for India. The Maldives, once under India’s strategic influence, has started hedging its bets by playing China against India. This could weaken India’s influence and foster a more competitive strategic environment in India’s neighbourhood. It risks a serious loss of India’s diplomatic leverage in the region and its neighbourhood-first policy. In the long term, it could limit India’s ability to operate freely in the region.

Chinese investments in ports, such as Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Gwadar in Pakistan, and potential future port deals in the Maldives, raise concerns about their civilian-military dual use. They could be exploited during crises or conflicts for military logistics, surveillance, or even deployment. China’s debt-trap diplomacy is now a well-established phenomenon. The Maldives’ debt to China, estimated to exceed $1.4 billion, is a point of concern.[22] This disproportionately high debt for the small economy of an island nation like the Maldives gives China leverage over its national policies, foreign policy alignment, voting behaviour at the UN, and defence procurement decisions. India observed this in the ‘India Out’ campaign and Muizzu’s directive asking the Indian Military to leave Maldivian soil.

Chinese forays into the Maldives require India to be vigilant, pursue proactive diplomacy, and foster regional cooperation to safeguard freedom of navigation, sovereignty, and stability in the IOR. India’s challenge will always be to curb the growing Chinese influence while maintaining its own, without appearing overbearing.

Resetting Relations

Rebuilding a damaged relationship between two countries requires ongoing diplomatic effort, including open dialogue, resolving core issues, and promoting mutual understanding. It also involves establishing trust through economic collaboration, cultural exchange, and people-to-people links.[24] The shifting geopolitical winds in the IOR, with the Maldives serving as a key example of this trend, require continuous realignment of relations – strategically, economically, and diplomatically.

For India, the Maldives is not just a neighbour defined by geography, history, and shared maritime interests. It is also a strategic maritime partner. The level of influence India has over the Maldivian islands affects its ability to monitor the central Indian Ocean, approach India’s west and south coasts, and respond swiftly to maritime contingencies. China’s increasing influence over the Maldives, by fostering dependence on it, is diminishing India’s primacy in its near-seas approach. The current strategic landscape in and around the Maldives therefore requires agile navigation to maintain a lasting relationship.

On a positive note, although President Muizzu came to power on an anti-India plank and initially focused on strengthening relations with China, he swiftly recognised the risks of increasing debt, the dangers of regional influence competition, and the inherent contradictions in balancing strategic interests amid rivalry between India and China. He understood that the Maldives cannot give the impression that it wants to distance itself from India and the associated economic and developmental support that entails.

Within about a year of his presidency, President Muizzu increasingly recognised that a confrontation with India would not bring any advantages. Understanding that constructive engagement with India would better serve Maldivian national interests than conflict, he started adjusting the Maldives’ foreign policy. Realising that having diverse partnerships, rather than depending too much on a single external actor, provides greater security and economic stability, he aimed to maintain India’s goodwill and acknowledge its key role in the region. This has led to a softening of anti-India rhetoric and a renewed willingness to engage, indicating a careful shift in approach that seeks to assert sovereignty while avoiding the strategic costs of alienating India.[25]

His visit to India in October 2004 reaffirmed the Maldivian commitment to developing “continued close relations” and enhancing bilateral cooperation. During that visit, a vision statement for a comprehensive economic and maritime security partnership was adopted, emphasising connectivity, capacity building, and counterterrorism cooperation. “The Maldives is India’s key maritime neighbour in the Indian Ocean Region,” India’s Ministry of External Affairs stated in announcing Muizzu’s visit. On this occasion, Prime Minister Narendra Modi discussed “energy, trade, financial linkages and defence cooperation” with him. India approved a $400 million currency swap agreement to support the cash-strapped Maldivian economy and also discussed a free trade agreement with him.

This visit of President Muizzu in October 2024 laid the groundwork for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the Maldives in July 2025. During the Prime Minister’s visit, the two sides announced the start of negotiations for an India–Maldives Free Trade Agreement (IMFTA), which will significantly enhance bilateral trade, tourism, and investments. Defence cooperation received a major boost through the joint inauguration of a new Ministry of Defence building in Malé, constructed with Indian assistance. Infrastructure development also took centre stage during Prime Minister Modi’s visit – 3,300 social housing units in Hulhumalé were handed over; projects in Addu City and six High Impact Community Development Projects were inaugurated; and 72 vehicles and assorted equipment were provided to support public services. India gifted two Bharat Health Initiative to Sahyog Hita and Maitri (BHISHM) health cube sets for emergency medical and disaster relief.[26]

Mutual security was another important aspect of the reset, during which President Muizzu condemned the April 2025 Pahalgam terror attack in India, which killed 26 civilians. President Muizzu called India the Maldives’ “closest and most trusted partner” and stated that “no one can break India–Maldives ties”.[27] Prime Minister Modi’s response to the Maldives’ “special place” in India’s Neighbourhood First policy, describing the relationship as “not just diplomacy, but a relation of deep affinity,” signalled a mutual desire from both leaders to foster political capital centred on stability and cooperation rather than confrontation.[28]

Learning lessons from the past, India has also increased its engagement across party lines. During his visit, Prime Minister Modi interacted with prominent figures from the ruling party, including those who played a crucial role in the “India Out” campaign and are close to China. He also held a meeting with notable figures from the Jumhooree Party, Maldives National Party, and Maldives Development Alliance. Separate meetings took place with the main Opposition, the Maldivian Democratic Party, and former President Mohamed Nasheed. These engagements emphasise India’s efforts to make relations non-partisan and resilient to turbulent domestic politics.[29]

Prime Minister Modi’s recent visit to the Maldives indicates that India is moving past previous issues and remains optimistic about future cooperation. There is confidence that the Maldives will recognise that regional security is a shared concern. However, it must be acknowledged that the Maldives’ economic stability will continue to pose a significant challenge for India. The Maldives will persist in engaging with China to seek assistance and investments to diversify and avoid over-reliance on India. Therefore, India should stay alert and continue to leverage its influence to protect and advance its interests.[30]

Conclusion

The Chinese ventures into the Maldives and other island nations in the IOR are not isolated events, but part of a wider strategic approach with significant strategic, economic, and security repercussions. The Maldives is at a crucial strategic turning point. While India cannot impose its will on the Maldives’ sovereignty, it must defend its maritime interests through patient diplomacy, strategic investments, and regional partnerships. Securing a stable and cooperative Maldives is essential for protecting India’s strategic frontiers in the Indian Ocean. It requires vigilance, proactive diplomacy, and regional collaboration to uphold freedom of navigation, sovereignty, and stability in the IOR.

President Mohamed Muizzu’s October 2024 visit signalled that Malé regarded engagement with New Delhi as vital. It not only reoriented India–Maldives relations towards mutual benefit but also opened the door for the Indian Prime Minister’s visit. Prime Minister Modi’s 2025 trip to the Maldives was a comprehensive effort to restore and enhance strategic, economic, and environmental ties with the island nation. By addressing past tensions, bolstering economic support, and aligning security interests, India reaffirmed its role as a reliable partner in a geopolitically competitive region.

For the Maldives, its leadership recognised India’s centrality and reliability, while understanding that sustained outreach to China does not need to come at the expense of ties with India. The lesson was clear: burning bridges with India could incur long-term costs. The Maldives must therefore avoid zero-sum geopolitical games, while India must continue to deliver on its commitments with speed, scale, and sensitivity.

Moving forward, the focus must remain on strengthening this trust. As Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri noted during the special briefing by the MEA on the Prime Minister’s visit to the Maldives, “There will always be events that will impact or try to intrude on the relationship. But I think this is testimony to the kind of attention that has been paid to the relationship, including attention at the highest levels… We’ve continued to work at it, and I think the result is there for you to see.”[31]

Author Brief Bio: In his distinguished career spanning four decades, Air Marshal P.K. Roy PVSM, AVSM, VM, VSM, has played a crucial role in strengthening India’s maritime and aerial capabilities. He has served as the Commandant of the renowned National Defence College of India and later as the Commander-in-Chief of the Andaman and Nicobar Command, India’s only tri-service integrated command. After retiring, he remains actively involved in strategic and security debates and discussions in India.

References:

[1] Picture: India: A Credible Leader for the Indian Ocean Region, Vikas Kalyani, January 27, 2021, https://chintan.indiafoundation.in/articles/india-a-credible-leader-for-the-ior/

[2] Mapping the Indian Ocean Region, by Darshana M. Baruah, Nitya Labh, and Jessica Greely, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/06/mapping-the-indian-ocean-region?lang=en Published 15 June 2023

[3] Indian Ocean Rising: Maritime Security and Policy Challenges Edited by David Michel and Russell Sticklor, ISBN: 978-0-9836674-6-9

[5] The Chatham House 2024 Asia-Pacific Report

[6] Reinvigorating India’s ‘Act East’ Policy in an age of renewed power politics, Chietigj Bajpaee, 12 August 2022, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09512748.2022.2110609#abstract

[7] https://www.narendramodi.in/reader/act-east-journey-india-s-strategic-design-for-the-indo-pacific

[8] Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean Region, https://ifcior.indiannavy.gov.in/ ,

[9] Towards a Cohesive Maritime Security Architecture in the Indian Ocean, Sayantan Haldar, dt 26 September 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/research/towards-a-cohesive-maritime-security-architecture-in-the-indian-ocean

[10] Maldives country profile, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-south-asia-12651486

[11] SIGNIFICANCE OF THE MALDIVES TO INDIA, Ritika V Kapoor, 09 April 2020, https://maritimeindia.org/

[12] ibid

[13] https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/maldives

[14] https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2022/11/the-maldives-tug-of-war-over-india-and-national-security%3Flang%3Den

[15] Strategic Synergy in the Indian Ocean: India-Maldives Relations, Dr Gedam Kamalakar, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388279376_Strategic_Synergy_in_the_Indian_Ocean_India-Maldives_Relations ,

[16] Blue Diplomacy: The Way Forward for India- Maldives Ties in the Indian Ocean Region, By Aishwarya Singh Raikwar, https://www.wgi.world/blue-diplomacy-the-way-forward-for-india-maldives-ties-in-the-indian-ocean-region/

[17] ibid

[18] India-Maldives War of Words on Social Media Triggers Diplomatic Row by Sudha Ramachandran https://www.drishtiias.com/daily-updates/daily-news-editorials/shifting-tides-of-india-maldives-diplomacy

[19] https://thediplomat.com/2024/01/ ,

[20] The Observer Research Foundation reported in its 2024 South Asia Brief that

[21] Maritime Security issues from the Perspectives of India, Sri Lanka and Maldives, By M P Muralidharan, NDIA AND THE ISLAND STATES IN THE INDIAN OCEAN Evolving Geopolitics and Security Perspective, INDIAN COUNCIL OF WORLD AFFAIRS 2023.

[22] https://asia.nikkei.com/politics/international-relations/maldives-owes-china-1.4bn-says-finance-minister

[23] Picture: India And China face off, April 22, 2019, Dr. David Brewster, https://ipdefenseforum.com/2019/04/india-and-china-face-off/

[24] DIPLOMATIC BLUEBOOK OR 1972, Review of Foreign Relations, PIB Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan

[25] Why is pro-China Maldives leader Muizzu seeking to mend India ties? https://www.aljazeera.com/news Sarah Shamim 10 October 2024

[26] https://www.idsa.in/publisher/comments/resetting-ties-modis-visit-reinvigorates-india-maldives-relations

[27] [5] “Maldives President Mohamed Muizzu Calls India ‘Most Trusted Ally’, Hails First Responder Role”, Hindustan Times, 26 July 2025.

[28] “India-Maldives Relations are Centuries Old: PM Modi in Malé”, ANI News, 26 July 2025.

[29] PM Modi’s engagement with the Maldives shows India is playing the long game, Aditya Gowdara Shivamurthy, Originally published in The Indian Express 02 Aug 2025, https://www.orfonline.org/research

[30] ibid

[31] Transcript of Special Briefing by MEA on Prime Minister’s visit to the UK & Maldives (22 July 2025), https://www.mea.gov.in/media-biefings.htm?dtl/39815/Transcript_of_Special_Briefing_by_MEA_on_Prime_Ministers_visit_to_the_UK__Maldives_July_22_2025

[23]

[23]