India is at a “chauraha”. A confluence of events makes the present a determining moment for India’s economy. Like any “chauraha,” there is “static” from bystanders offering guidance—sometimes of questionable quality or intent.

One (non!)-option is returning to the license raj with public-sector domination of the economy’s “commanding heights”. The overly-regulated structure benefitted powerful participants who played the rule game best, rather than the underprivileged. Equally avoidable is the second option of taking on sporadic, incremental reforms. In the best case, this may achieve high single-digit growth levels for a while. Both options do not do India justice, and fail in two important objectives – creating employment and pulling people rapidly out of poverty. In a competitive world, India risks falling behind countries that make better policy choices.

The right path is to take inspiration from “bahu-yuddha” – using the opponents’ strengths and one’s flexibility to win. We respond to COVID19 and the global economic situation by doubling down on change and undertaking large-scale transformational measures that make India a preferred destination for investment, technology and skills. Reforms must focus on ease of doing business and “minimum government”, improving productivity and making India a magnet for capital flows while strengthening a targeted social safety system that helps the real under-privileged.

A Multi-generational Opportunity

The chance to revitalise our economy into a global leader has transpired through a coincidence of events – some are years in making and others are unexpectedly sudden.

COVID: Beyond being a humanitarian disaster, the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the global economy. Analysts estimate losses to be in the range of USD 25-50 trillion. Beyond numbers, changed behaviours have upended established business models and caused drastic changes in the methods and practices across almost every aspect of our economies. Changes that would otherwise have taken years, have happened in months. Covid and the resultant lockdown, have proven the efficacy of remote and dispersed operations and delivery. It has also caused lasting damage to sectors dependent on the traditional in-office operations.

The impact of COVID has been widely differentiated – across countries and individuals. The poor have suffered inordinately more. Global trade has also been disrupted – though may be a positive development for us by reinforcing the importance of supply chain players who have the safety net of a large domestic market.

Trump, Brexit and loss of faith in “Internationalism”. Trump’s rhetoric on “America first,” Brexit and multiple political wins by parties that are inward-looking and anti-multilateral trade has created uncertainty around WTO, NAFTA et al. Trump’s successful negotiations on some bilateral trade deals, further encouraged this trend. Counter-intuitively, this helps countries that have clearly defined their trade priorities and are ready to go the extra mile to close deals quickly. Biden’s election has brought multilateralism back on the table – and this too can help India especially vis a vis China.

World “Breaks-up” with China. Less than perfect disclosures about COVID19, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) pushing some of the world’s poorest countries into inextricable debt traps, aggression – military, economic and territorial, and unabashed muscle-flexing, made the world’s view of China less rosy. Questions are being raised about “trusting” China as a partner. Suddenly the world is looking at China++ strategies, and pushing back on China’s unilateral claims like hegemony over the South China Sea.

Global macro situation that can “subsidise” reform and pivotal changes. Most OECD countries have signalled the maintenance of an easy monetary stance at-least till 2022. Global energy prices are likely to remain low. This has created “headroom” for policy risk taking by reducing risk of external price shocks. Multiple rounds of quantitative easing around the world have created a huge global pool of liquidity waiting for “productive” investment opportunities. This is especially relevant because we do not have indigenous capital in the scale needed to transform us into a first world economy.

4th (or is it already 6th!) Industrial Revolution – Coming Omnipresence of AI/ML, Nanotechnology and Biotech. It’s not yet “Machines Rule” but AI-ML will inevitably impact every aspect of our lives. How we cook, to how we run cities, how healthcare is delivered, how we conduct research, how we manufacture etc. – old process flow-charts will be thrown out of the window. There will be disruption. Positively, mankind will acquire capabilities that Captain Kirk might have described as “god-like”. Negatively, the weakest, least educated and underprivileged may face dislocation including at-least temporary unemployment. At the 8th C D Deshmukh lecture, Dr David Lipton referred to the possibility of 375 million people globally, losing their jobs due to technology. Mastering and pioneering cutting edge technology will differentiate countries, as well as determine the quality of employment we offer our citizens.

Emergence of true, and confident “entrepreneurial” class in India. Too often, private “old” family run businesses have been described as entrepreneurs. Old business-houses have contributed to India’s development but entrepreneurship is different. The last three decades have seen a new class of first-generation entrepreneurs coming to the fore – rarely from a wealthy background; building businesses based on “new” ideas for products and services; tech savvy; and, not afraid of failing. Just as TCS and Infosys spawned an entire IT industry, the unicorns created in the last decade are inspiring a generation of young entrepreneurs. This development, and the example of sectors like IT and Pharma that succeeded with minimal government support has put to rest the need for a “mother government”. It is a point that PM Modi has highlighted recently in assigning the private sector a major role in India’s future development.

India has the ingredients to exploit the opportunity – a large domestic consumer market, favourable demographics, pool of educated and skilled human capital, democracy, established judicial-administrative institutions and processes etc. Leveraging our strengths, in a timely and coordinated manner, will allow us to make massive gains in the global economic hierarchy. We will also transform the living standards of our most underprivileged citizens – fulfilling Gandhiji’s vision of Sarvodaya through Antyodaya.

One Still Has To Hit The Ball To The Boundary: Making The Most Of Our Opportunity

History is a litany of cautionary tales about opportunities – countries that made the most of them, and those that failed to do so. Spain discovered the “new world” but England colonised it; the East Asian Tiger economies started at a similar level but Korea and Singapore made the most of opportunities while others floundered; and closer to home our own dalliance with socialism, labyrinthine regulations and maximum government – which led to anaemic rate of growth for decades.

India has made progress in cutting through the maze. Narasimha Rao, even if under duress from multilateral institutions, took courageous policy decisions to start opening up the economy. Since then, there have been small steps that continued liberalisation. Unfortunately, we also suffered from regulatory inertia. Often, at the slightest hint of adversity, the vines of regulatory over-reach and complexity reappeared like tenacious weeds. Modi 1.0 made Minimum Government, Maximum Government a stated policy. Hundreds of outdated laws were junked. Approval processes were streamlined. Reforms like GST were executed. India was open for business.

The recent budget unveiled by Nirmala Sitharaman, together with the earlier “mini-budgets” are a gigantic step forward. It is, perhaps, the most radical set of reforms since Narasimha Rao’s. Coping with the impact of the pandemic, the government has stepped in to reignite demand and investment. It opened up sectors for private participation, and took innovative steps to spur entrepreneurship. Investments will be made in rural India to spark agricultural productivity and developing rural logistics. As a response to the unprecedented COVID19 crisis, this is a dream budget.

Now we have to construct the edifice of a sustainable, strong, world-leading economy on the foundation of this budget. This task can be viewed through two lenses – the macro-strategic view covering broad themes, and a micro, sector specific set of policies.

The Macro-Strategic Approach And Policies

Convergence in the “strategy” of policy making. Our economic policy sometimes appears to be formulated in isolation. We need a convergence of our multifarious strategic interests – external affairs (mainly, response to China); defence – exploiting linkages between large purchases and access to latest civilian technology; commerce and industry – ensuring we have access to capital and the latest technology to power the creation of champion industries; health etc. Convergence may help build consensus around bolder bets as a country, in contrast to a “middle path” without conviction. For example, we made the decision to work more closely with the US – given the advantages that such cooperation brings – reforms we need – transparency, corporate governance etc., and the recognition that the US represents the single largest pool of capital. It may also mean preferential treatment to particular countries in order to access deeper capital or technology pools.

Dismantle Regulatory Distortion Of The Markets and Pricing. Across sectors, the Indian economy has been distorted by subsidies, sops and other artificial market deviations. This has led to over-use of inputs and over-concentration of certain crops in agriculture. In industry, it has bred practices of “gaming” of rules just to access tax breaks and subsidies. We have kept uncompetitive, unprofitable industries going for years based on a misplaced sense of indispensability. Worst of all, even the most well-intentioned market interventions tend to have large leakages – with benefits not reaching the people who really need it. Barring exceptional circumstances, we need to map out a path for the government to move out of a price-determiner or market-disrupter role.

Let execution and policy making reflect the true breadth and ambitions of Atmanirbhar Bharat. The grandness of vision that PM Narendra Modi has proposed needs to be suitably executed. Instead of understanding that it is an aspirational “big tent” with multiple elements, people have inaccurately tried to pigeon-hole it into simplistic boxes – strong manufacturing, import substitution etc. It is much more. It is a dream where the gap between being best of class and market leader in India, and internationally, is minimised. Across sectors, Indian products and services must aspire to reach world leading standards. To get there, India remains welcoming to global capital, global ventures and global technology. Indian ventures may get assistance – to improve, build scale and do research, but not protective barriers to foster suboptimal businesses.

Extension, continued tightening of benefits delivery. Moving out of broad subsidies and price support does not imply reduction of assistance to the truly needy. In fact, it will support and enhance support. Expansion of DBT has been one of the biggest successes under PM Modi. This needs to be extended beyond just cash transfers and into “social parachute” services – unemployment benefits, insurance for exigencies, access to medical and education services. Savings accruing from reduced subsidies and price supports should be channelled into direct benefits for the most under-privileged. This re-purposing of benefits has to be accompanied by comprehensive, verified and up-to-data so that benefits go to intended beneficiaries.

Push Integration into Global Supply Chains. Global supply chains are “sticky” business. Once in, business is significantly easier to hold on to. There are the added benefits of correlated investment and capital that follow the supply chain. The advantages of scale that our manufacturing can enjoy while catering to a global market are hard to imagine.

Source: “High-Technology Exports (Current US$)”, The World Bank, 2007-2018

Inclusion and Participation. Inclusion has often been used in narrow contexts such as financial, employment etc. We need to broaden inclusion and participation to cover every aspect of our social-economy. Use of technology for delivery of education, financial services, medical services are an immediate need. Experience gained during the COVID lockdown in internet-based work collaboration and remote working needs to be translated into greater participation in our economy for women, the differently enabled, those living on the margins of society, residents of our North-east etc. Similarly, technology as a tool should be made available to the largest portion of our citizenry with the old public library becoming the new digital services centres.

Beyond individuals and families, inclusion and participation are also relevant to corporate entities. There is investment needed in broadening corporate credit delivery so that fiat-based credit provision is not needed. Similarly, mechanisms that reduce the cost of technology for MSMEs are needed. Last but not the least, we must enforce our competition regulations and provide a level playing field. Need for transparent handling of competition breaches must go hand in hand with giving the Competition Commission and similar regulators real punitive “teeth”.

Climate and Sustainability Integral To Real Development. Modi government was the first to stop treating development and environmental-protection as mutually antithetical. The recentlandslides and break-up of the glacier in Uttarakhand is a stark reminder about the fragility of nature and our ecosystems. In fact, Modi 1.0 had put a stop to further hydropower projects in Uttarakhand. We now need to marry environmental concerns with our economic development agenda. Reduction of carbon footprint, conservation of water, air-quality et al need focussed efforts. Energy needs to turn towards renewables as a major and not marginal source. Electric transport must become our targeted norm over the next 15 years. Many of these are “social good” investments that the government has to make, since the benefits will be spread over decades.

Recalibrate Marketing & Policy Incentives For Foreign Investment. India’s push for foreign investment has been focussed on financial institutions, largely by the broking community. Investor interactions have increasingly narrowed to roadshows for foreign funds and asset managers. This prioritisation needs to be reversed immediately with focus on strategic investors for companies setting up businesses in India. These investments are very long term and establish a continuing flow of capital and technology in to the country. Attracting these investments requires marketing, and incentives over a period of time. Some policy measures to attract such investments are:

- Establish tax holidays and other financial incentives based on investment size.

- Establish targets for some countries with greater investment potential like the US, Japan and Taiwan and focussed interactions with the largest corporates to customise incentives.

Commitment To Intellectual Property Rights and Contract Enforceability. India needs foreign capital and technology. Both have been curtailed by the issue of IP rights and contract enforceability. Whether it be the impunity of JV partners “borrowing” technology and starting parallel production, or toll road operators being evicted for “earning too much,” investors get spooked. Steps need to be taken to reassure potential investors through accelerated judicial processes, special arbitration cells and similar policy measures.

Bringing it all together: Productivity and Invest-ability. Just as Arjun remained focussed on the “eye of the bird,” our macro policy measures need to come together and focus on improving productivity across sectors of the economy. Higher productivity will naturally make India an attractive investment destination – the result will be self-sustaining supply of global capital to drive our economy growth.

There is a subtle message in the ordering of the policy recommendations above. By not putting inclusion-participation and sustainability-environmental protection at the end of the “developmental” recommendations, we want to reiterate the integral role these play. We will not succeed if we treat them as an afterthought.

The Micro Lens: Sector Specific Policy Approaches

Manufacturing. We need a leap-frog strategy for participating in the global value chain. Low-end, cheap assembly-manufacturing coupled with depreciated currency fostered exports approach that China exploited and Vietnam, Thailand et al are trying to mimic is the past. Our industrial sector needs to focus on the higher end of value addition, making complex components, high end machinery etc. and scale. We can use our large domestic consumer base as a platform for commercialising new technology. Focus should be on bringing in OEMs rather than their contract manufacturing. Scaling up will happen if our manufacturers can become internationally competitive and not protection enabled national champions. International competitiveness will draw in the capital needed to finance the scaling up.

Agriculture. In a recent address, while commenting about development in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, CM Yogi Adityanath sought a change in “Mansikta,” a need for positivity. For too long, agriculture has been negatively depicted as an unproductive, subsidy soaking sector holding the country back. Small farmers were profiled the worst. This false “Mansikta” must change. The bane of our actual farmers is “access” – to market (for inputs and produce), to water and land. Price distortionary policies and productions risks compound their misery. We need massive investment in building this “access”. Technology can play a role in improving input access – be it seeds, fertiliser or agri-tech knowhow about improving productivity. It can also help regulate illegally incentivised use of inputs. During cultivation, we need to figure out ways for farmers to reduce their costs for e.g. in use of machinery, irrigation. Finally, the small farmer needs access to the markets without losing value to multiple intermediaries. The MSP regime, accessed by less than 15% of our farmers has distorted cultivation towards low value, land-water guzzling crops. More than MSP, we need wider procurement infrastructure that benefits more farmers. FPOs (Farmer Producer Organisations) and similar organisations hold out great promise and need to be fostered. FPOs are more dynamic rather than the institutionally rigid cooperative institutions, and provide farmers with pricing power and buyers with reduced transactional expenses. Some FPOs will fail – and we need to let them – so that we eventually have a network of viable FPOs.

Agriculture policy will not be complete without incentives for organic farming. Organic farming has shown equal or better productivity but needs a 2-3 year conversion period. Governments, both centre and state, must come together to formulate a plan to encourage, and subsidise the cost of this conversion. We also need to encourage supplementary income from “remote working” that allows rural citizens to take up “urban” opportunities. This is also an achievable objective in the post COVID era.

Change Infrastructure Priorities. Infrastructure has traditionally meant roads, ports, power generation. There is a need to shift to “softer” infrastructure that supports the next leap in national productivity – healthcare, education, clean energy. Healthcare has already been a centrepiece of spending in this budget – following on the ramp-up in health infrastructure as a COVID response. Similarly, the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP) has set out the path to modernise Indian education, and more importantly help our educational system produce more fit-for-employment students.

Financial Sector. The recent announcement about disinvesting in two banks is a positive step. Eventually, the government should turn this objective on its head and keep only 2-3 banks. Continued government ownership and interference will only consign them to the fate of Air India and BSNL. A path to privatisation—capital, management change and empowerment etc. must be planned and timelines put in place. Pathbreaking steps have been taken in Insurance, capital markets as well as resolving bad loans. Many of these have not received adequate attention.

The money released from disinvestment (and by avoiding repeated recapitalisations) can be used to broaden our financial markets. More “types” of capital need to be made available. This needs more sophisticated exchanges, specialised institutions, access to financial technology and investments in effective regulation that truly prevents systemic risks.

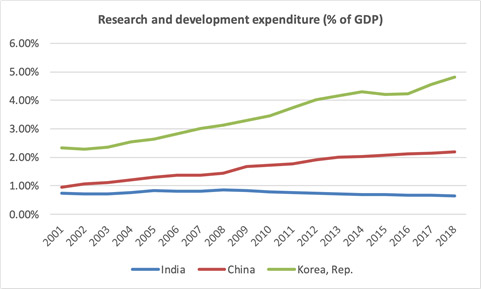

Research and Development (R&D). R&D is not a sector, but needs separate attention. For India to gain from global advances in technology, we need to be plugged into the global R&D ecosystem. Else, we will be like the Road-runner cartoon figure – always running to catch up and paying huge premia for the latest technology. We need a way to draw in global R&D into an onshore presence. Initially, our support role, clinical trials, reverse engineering etc., can help draw in research labs but there has to be prioritisation of original research. This needs to be incentivised commercially. We need a comprehensive policy that draws in the equivalent of the Teslas and Bell Labs to set up research labs in India.

Source: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/public-licenses#cc-by

Conclusion

India is ready to fulfil its economic potential. Global conditions are conducive, and in fact need a resurgent India. It needs courage and conviction to take on multiple initiatives across sectors, to throw off the yoke of unwieldy policies and to overcome our own vested interests and naysayers. It also needs consistent prioritisation for providing relief to our poorest citizens. The “sunahri chidiya” is ready to fly.

Author Brief Bio: Saket Misra is an investment banker and Advisor, Poorvanchal Vikas Board and Shreyam Misra is studying Economics at Williams College, USA.

References:

- Sukhpal Singh, “Future of Indian agriculture and small farmers: Role of policy, regulation and farmer agency” https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/future-of-indian-agriculture-and-small-farmers-role-of-policy-regulation-and-farmer-agency-75325 published on 02 February 2021

- Rumki Majumdar, “India The year that was and will be” https://www2.deloitte.com/za/en/insights/economy/asia-pacific/india-economic-outlook.html, published on 08 January 2021

- Kapil Shah, “The future of Indian agriculture lies with ‘atmanirbhar’ farmers” https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/the-future-of-indian-agriculture-lies-with-atmanirbhar-farmers-75228, Published on 27 January 2021

- Shelly Anand, “NEP 2020: A roadmap to success”, India Today Insight, https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/nep-2020-a-roadmap-to-success-1767976-2021-02-10 , published on 10 February 2021

- Ram Krishna Sinha, “National Education Policy: Why education must be anchored in quality and equity”, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/governance/national-education-policy-why-education-must-be-anchored-in-quality-and-equity-74492, Published on 02 December 2020

- The 8th NCAER C. D. Deshmukh Memorial Lecture 2020, India in a Changing World by David Lipton, First Deputy Managing Director, The International Monetary Fund https://www.ncaer.org/event_details.php?EID=271&EID=271 , 13 February 2020

- Kogila Balakrishnan, Saurabh Kukreja, “Can India be the Next Global Manufacturing Hub?” https://idsa.in/issuebrief/india-next-global-manufacturing-hub-kogila-saurabh-131120, 13 November 2020

- TN NINAN, “Like it or not, future of Indian economy will have to be built on services, not manufacturing”, https://theprint.in/opinion/like-it-or-not-future-of-indian-economy-will-have-to-be-built-on-services-not-manufacturing/590613/ , 23 January 2021

- Naveen Jindal, “2020 could be for manufacturing what 1991 was for our economy”, https://www.livemint.com/opinion/online-views/2020-could-be-for-manufacturing-what-1991-was-for-our-economy-11604415919783.html, 04 November 2020