Introduction

Population dynamics have an impact on a country’s economic and strategic capabilities. Sparsely populated countries may face strategic challenges, but large populations are not necessarily a blessing. An unbridled population growth can greatly hinder the development process, besides adversely impacting on the environment.

An article published in 2011,[i] on the implications and trends of India’s demographic outlook, came out with estimates of what India’s demography will look like in 2030. The article stated that as per UNDP projections, India’s population will exceed China’s by 2025, and that the crossover will in all probability occur well before that time, making India the most populous country in the world. This article was extremely prescient in its predictions, as India is set to overtake China’s population sometime in 2023, but more ominously, the article has predicted that India’s population by 2030 will be in the region of 1.5 billion people. Is this sustainable and can India afford to go down that path? What are the fissiparous tendencies that such a growth can have on Indian society? These questions need to be asked and more importantly, need to be addressed with urgency.

Population Growth over the last five decades: World Comparison

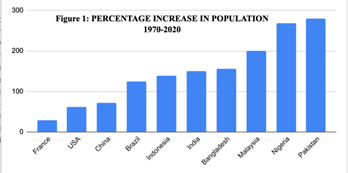

How has the world’s population increased over the last five decades? Statistics from 1970 onwards indicate that the Western world has successfully kept a lid on population growth. China too has been remarkably successful in controlling its population. However, most Asian and African countries have seen unprecedented population growth, which has hindered economic growth, created vast disparities between different economic groups, created water stress and food scarcity and led to fissures in society. All of these factors combined together have led to dismal standards of living for vast multitudes of people across the globe. The percentage increase in population over the last half-century for 10 countries is given in Figure 1.[ii]

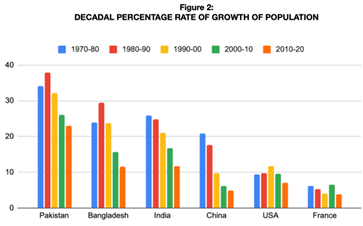

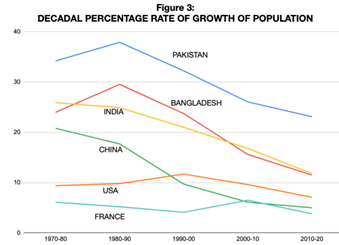

The decadal growth rate of population also makes an interesting study (Figures 2 and 3).[iii] Both the US and France, over the last half-century, have had a decadal growth of population below 10 percent for the period 1970-2020. This is true for most of the Western world. Low population growth has been a contributory factor to their ability to provide a high standard of living to their people and being classified as first-world countries. China, which imposed a one-child policy on its populace in September 1980 saw only a marginal decline in population growth for the first decade after the policy was introduced. The decade 1970-1980, prior to the introduction of the policy saw a decadal increase in the population of 20.8 percent. In the first decade after the implementation of the one-child policy (1980-1990), there was but a marginal decline, with decadal population growth at 17.7 percent. This indicates that the one-child policy was widely flouted by most residents. The next two decades saw decadal population growth dropping to below 10 percent, and for the decade 2010-2020, the population growth was just 5 percent. This is comparable to the population growth in France, which saw a decadal population growth hovering between 4 to 6 percent for the five decades 1970-2020. The US has also maintained for the most part, decadal population growth under 10 percent for the last five decades.

In the Asian subcontinent, the situation has unfortunately spiralled out of control. In Pakistan, the decadal population growth has been in excess of 30 percent for each of the three decades 1970-2000. A marginal decrease has taken place post-2000, with decadal population growth reducing to 26 percent and 23 percent for the decades 2000-2010 and 2010-2020 respectively. In real terms, the population of Pakistan has increased 3.8 times in the last half-century (1970-2020) and about seven times since the country achieved independence in 1947. This is clearly unsustainable. Bangladesh also has high decadal population growth, though their performance is far better than Pakistan. For the period 1970-1980, decadal population growth was 24 percent. This rose to 29.5 percent in the decade 1980-1990, which indicates that in the earlier decade following the Liberation War, large-scale migration of population had taken place from Bangladesh to India. Thereafter, decadal population growth witnessed a slight decline with population growth at 24 percent. Since then, population control measures appear to have been more successful, with decadal population growth at 15.6 percent and 11.5 percent for the period 2000-2010 and 2010-2020 respectively.

The statistics for India too are not very flattering and resemble to some extent the statistics of Bangladesh. The three decades 1970-2000 saw the decadal population growth hover between 26 percent and 21 percent. This is high and reflects a failure of the nation’s family planning programme. The decadal population growth dropped below 20 percent for the next two decades, touching 16.8 percent in 2000-2010 and falling further to 11.8 percent for the decade 2010-2020. This is still high though it now appears that India is closer to getting to grips with the problem. What remains of serious concern, however, is the wide variation in population growth between different parts of the country as also between different communities, which potentially can cause severe fissures in Indian society.

India and China: A Statistical Analysis

At times, when development or rather the lack of it is linked to excessive population growth, the nay-sayers promptly state that poor economic development is not due to unbridled population growth but due to socio-economic factors. Then they justify their assumption by giving a reference to China, quoting its spectacular economic growth despite it being the most populous country in the world. This is simply intellectually dishonest. Undoubtedly, poor socio-economic policies hinder economic growth, but unbridled population growth negates even the most pragmatic of economic policies and will invariably result in weakening poverty alleviation programmes. China’s spectacular rise is a result of strict measures to restrict family size; had such measures not been taken, the picture in China would have been rather gloomy.

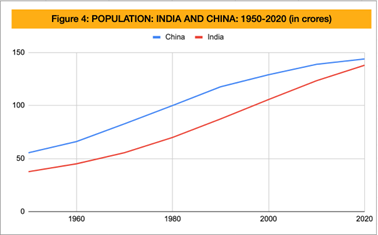

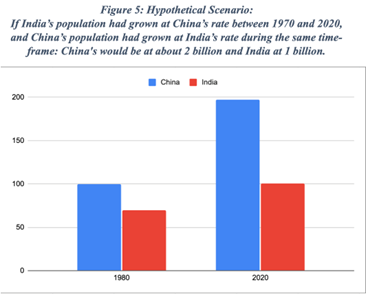

A comparison of population data between India and China—the world’s two most populous countries is indeed instructive. Figure 4[iv] shows the population of India and China from 1950 till 2020. China’s population, which stood at 55.44 crore in 1950 had almost doubled over the course of the next three decades to 100 crore by 1980. This was when China began its family planning programme, with its one-child policy. In 2020, 40 years later, China’s population stood at 143.93 crore, an increase of just under 44 percent. In comparison, for the period 1950-1980, China’s population had increased a whopping 80 percent. Had China continued with such a high rate of population growth, it would have crossed the two billion level mark by now (figure 5). What would be the impact on China if it had another 600 million mouths to feed and look after, can only be speculated, but undoubtedly, China would have still been a third-world country. As of now, while China’s decadal population growth has reduced to single digits, it is still higher than most European countries.

Now let us take a look at India. India’s population stood at 37.63 crore in 1950. In terms of comparison, this is less than the present-day combined population of Pakistan and Bangladesh. By 1980, India’s population had surged to 69.89 crore, indicating a growth of 85 percent. At this stage, India’s and China’s rate of population growth were almost similar. Over the next 40 years, the situation changed dramatically. In 2020, India’s population stood at 138 crore, an increase of a staggering 97 percent! Had India been successful in controlling its population as China had done, its present population would have been just over one billion (Figure 5). With 400 million less people, unemployment in India would have been minimal, the cities would not be bursting, pollution levels would have been under control and in all likelihood, India would have been a middle-income country.

Population Dynamics: Internal Fissures

The population growth of India is an area of concern, but more ominous is the fact that this population growth is uneven and could potentially create serious fissures in society on two counts. The first is related to a Constitutional provision. Article 81 of the Indian Constitution lays down the distribution of seats to each state based on their population, while Article 82 provides for the readjustment of seats in the Lower House, after each census. This delimitation was suspended in 1976 till the 2001 census, primarily because the Southern states had achieved a higher degree of population control than the states in the North. This was again postponed to 2026 by the 84th Amendment. In the revised allocation, the Northern states would have got a larger share than the South,[v] which effectively meant rewarding those states that were less effective in promoting small family norms.

Let us take the example of five northern states and five southern states to put the above issue in perspective. Based on population data, the Northern parts of the country have shown a higher rate of decadal population growth as compared to the Southern states which have achieved a certain measure of population stability. A readjustment of seats, carried out on the basis of Article 82 of the Constitution of India, could lead to a very serious North-South divide in the country, as the states which have a higher rate of population growth would stand to benefit in terms of seat share (Figure 6).[vi]

For the period 1970-2020, the population of five northern states viz. Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand and Rajasthan showed an increase in the population of 178 percent. These states have a combined representation of 164 seats in Parliament as of 2019. Based on the above, in terms of the Constitution, these five states will get seats in proportion to their population increase. Their seat share thus increases by 178 percent to a total of 455 seats.

In the five southern states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the states have a combined representation of 129 seats in Parliament as of 2019. The combined population of these five states increased by 102 percent over the period 1970-2020. Based on the population increase of 102 percent, their share of seats in the Lok Sabha would increase by 102 percent to give them a revised seat share of 260 seats. Based on percentage increase of population, the Southern states hence stand to lose significantly in representation in the Lower House while the Northern states, which faulted on population control measures, stand to gain.

Increasing seat share based on the proportional increase in population will hence disempower the South in comparison to the North, simply because they have carried out the required population control measures in a more effective manner than states in the Northern half of the country. This will create grounds for unrest with severe consequences. The solution hence would be to further defer the expansion, or to simply increase the number of seats in parliament in the same proportion as are currently existing. It must also be noted that even amongst the Southern states, population increase is not uniform as states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu have fared far better than Karnataka.

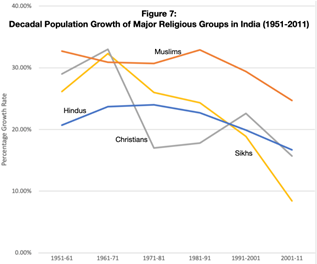

Religious fault lines too are beginning to appear because of uneven growth of different religious groups. Data available till the 2011 census indicates decadal population growth of all religious groups has declined but the rate of decline is different for different religious denominations (Figure 7).[vii] For each of the decades from 1951-2011, the decadal growth of the Muslim population has been about 10 percentage points higher than non-Muslims. In 2011, while the decadal growth rate of non-Muslims is veering towards the 10 percent decadal growth mark, the decadal growth of the Muslim population remains above the 20 percent decadal growth mark. In states like West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, UP and Assam, this is manifesting in societal tension which has the potential to lead to communal discord and splitting of communities on communal lines. Here too, as in the North-South divide, those religious groups which have been more effective in population control measures stand to lose out to those that have disregarded the same. Obviously, there is a need to implement strict family planning norms through a series of incentives and disincentives. The aim must be to get all groups to limit decadal population growth to between 0 and 5 percent.

To conclude, India as of now is on a cusp, where the country can break out as a middle-income country by 2047. This process will be greatly facilitated by the implementation of population control measures, uniformly across all strata of society and across the length and breadth of the country. This needs to be a priority call for India’s polity and civil society, to preserve the unity and integrity of the nation, prevent fissiparous tendencies and for the economic welfare of all sections of India’s population.

Author Brief Bio: Maj. Gen. Dhruv C. Katoch is Editor, India Foundation Journal and Director, India Foundation.

References:

[i] India’s Demographic Outlook: Implications and Trends: An Interview with Nicholas Eberstadt, available at https://www.nbr.org/publication/indias-demographic-outlook-implications-and-trends/

[ii] Data sourced from macrotrends.net for respective countries

[iii] Data sourced from World Bank Group

[iv] Data Sourced from the World Bank: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CN and https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=IN

[v] https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/article-81-constitution-explained-why-lok-sabha-is-still-543-6067542/

[vi] Data sourced from the Census of India