Abstract:

The 21st century global order has witnessed a significant shift towards the maritime domain, geopolitically and geo-strategically. The Indo-Pacific strategic space has gained importance and increasing number of nations are beginning to maintain their strategic presence in the region. The strategic deployment of assets has political, economic and military connotations. The Indo-Pacific strategic construct and the corresponding formation of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD), puts India in a significant position within the global power play. However, the “Indo” part of the Indo-Pacific must be understood in its entire strategic context. The Indian establishment on its part has shown strategic intent in line with the global expectations. The “Security and Growth for All in the Region” (SAGAR) declaration by Prime Minister Modi, is the first major geopolitical declaration by India, to be diplomatically seen as the leader in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). The Government of India, on its part, has further announced multiple mega projects like the “Sagarmala”, “Bharatmala”, “Inland Water Transport (IWT)” and many more to realise the SAGAR vision on ground. Maritime governance is a critical aspect that merits attention to manage the surge in maritime activities on all fronts. The Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is a term that has the potential to enable enhanced governance, however the conventional MDA has remained security driven and failed to penetrate into the other stakeholders. The second major drawback of the MDA has been that it has remained on surface. Given the vast undersea resources along with disruptive means available today to access the underwater domain, this is a major limitation. A comprehensive safe, secure, sustainable growth model that can address all the challenges and opportunities is required.

The Maritime Research Centre (MRC), Pune has proposed a comprehensive Underwater Domain Awareness (UDA) framework. This encourages pooling of resources and synergising of efforts across the stakeholders, namely maritime security, blue economy, marine environment & disaster management and science & technology. The UDA framework adequately addresses the policy, technology & innovation and human resource development requirements to be able to project India as a major maritime nation globally. India, with its geo-strategic location and vast maritime frontiers, cannot afford to remain a continental nation anymore. Massive acoustic capacity and capability building on multiple fronts is inescapable. In this paper, we present the infinite possibilities in the new global order. The Indo part of the Indo-Pacific and how India needs to gear-up in this new strategic context has been elaborated in depth. Young India is a massive resource. This could however become a huge challenge, if we as a community, fail to channelize their energy and aspirations in a constructive manner. “Maritime India with more Depth Underwater” is probably the way forward.

Introduction

The Indo-Pacific strategic construct has increasingly found more and more resonance among the global powers. Initiated by the Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, while delivering his address to the Indian Parliament in 2007, he referred to the “confluence” of the Indian and Pacific Oceans as “the dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and of prosperity” in the “broader Asia” [1]. It got symbolically linked to the “Quadrilateral Security Dialogue”, referred to as the QUAD, comprising of Australia, Japan, India and the US. The QUAD regained its relevance geopolitically during the pandemic with the growing assertion by China in global matters. The obvious belligerence from the Chinese, has probably brought the erstwhile dominant global powers to align themselves either way. The Germans and the French have also announced their participation in the Indo-Pacific strategic interaction [2].

The role of India in the Indo-Pacific strategic construct is significant in many ways. It brings India in the centre stage of global power play and India can no longer choose to remain a silent spectator. The Indo-Pacific is an outright maritime strategic construct and thus, India has to evolve itself as a major maritime power. The Indo-Pacific is defined as the tropical littoral waters of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean as shown in figure-1 [3]. The term tropical littoral waters bring with it, multiple unique challenges and opportunities. The “Indo” part of the Indo-Pacific demands that India invests significantly in its maritime capacity and capability building to remain a major player in the IOR and beyond [4].

Fig. 1 The Indo-Pacific Region: tropical Littoral Waters [3]

The Government of India on its part has displayed significant strategic intent to alter the continental policy outlook, it has been criticised of, since Independence. The SAGAR vision announced by the Prime Minster has been regarded as the most significant strategic declaration with a regional outlook, far beyond its national boundaries. This vision, as stated by the Prime Minister, in his address to the Shangri La Dialogue at Singapore in 2018 has the following aspects behind the broad vision [5, 6]:

(a) It acknowledges the security concerns that we face in the region due to the political instability and the socio-economic status of the IOR rim nations.

(b) It recognises the tremendous economic potential that exists for the nations in the region to harness.

(c) It emphasises the need for regional consolidation and bringing together nations in the region and prevent extra-regional powers from meddling in our internal matters.

(d) It attempts to revive the rich maritime heritage we shared and rekindle the sense of pride in our rich culture and traditions.

The Government of India has matched up the big SAGAR declaration, with mega projects like the “Sagarmala”, “Bharatmala”, “Inland Water Transport (IWT)” and more, to prioritise the maritime capacity and capability building. Significant policy incentives have also been offered and additionally, multiple legislations have been brought-in, to demonstrate aggressive push by the government on multiple fronts [7, 8].

The Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is a term used in the global parlance for effective maritime governance. MDA is rooted in the ability to effectively monitor what is going on, at any moment in the entire maritime space. The MDA, as defined by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), is the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact the security, safety, economy or the environment [9, 10]. The MDA, globally, remained a security construct and continued to be driven by the maritime forces with far less transparency and minimal involvement of the other stakeholders. Even from a security construct, the underwater component of MDA that could be referred to as Underwater Domain Awareness (UDA) has remained neglected and fragmented even on a global scale [11].

Challenges and Opportunities

There are political, economic and military connotations of the Indo-Pacific construct, given the geopolitical and geo-strategic realities of the times we are in. To achieve a comprehensive safe, secure and sustainable growth model, for good maritime governance, we need to be aware of these ground realities. The tropical littoral waters are blessed with abundant undersea resources, both living and non-living, available for exploitation. The economic abundance coupled with political instability and corresponding lack of maritime governance makes it a perfect mix for extra-regional powers to get involved and exploit the region for their narrow-vested interest. The global energy reserves in the Middle-East and the growing economies in South East Asia, with vast energy requirements, ensures a steady flow of shipping lines from west to east and back with the finished goods. Thus, the Indo-Pacific has become a critical sea route for the global powers to maintain their military presence to ensure their strategic autonomy [12, 13].

The political instability has given space to non-state actors, some of whom are being used both by the regional powers and extra-regional powers as regular instruments of diplomatic influence in the region. The non-state actors with an asymmetric and disruptive technological edge are a formidable force to deal with using conventional military means. Security, thus becomes a major cause of concern from a governance perspective. The extra-regional powers at times, also find it easy to use the security bogey to push their military hardware at high cost to these nations in the region. Many nations in the region with meagre economic resources and massive socio-economic burden, are the biggest spenders on military hardware. The socio-economic quagmire, coupled with political instability, makes it easy for the extra-regional powers to keep the polity within and the governments in the region fragmented, and allows them to exploit the situation to their benefit. The misplaced priorities politically, makes it difficult to evolve effective governance mechanisms and reverse the vicious cycle. Maritime terrorism, piracy, IUU (Illegal, Unreported & Unregulated) fishing, unsustainable maritime activities and more, are thus on the rise and threatening the sustainable development goals across multiple dimensions. Political instability and overall lack of synergy at all levels negatively impacts maritime governance. [14, 15].

The economic aspect further has multiple dimensions and dynamics. The abundant undersea resources coupled with lack of knowhow and effective governance mechanism is a deadly recipe for higher political interference by the extra-regional powers. Nations with vast coastlines are not the major players in shipping, shipbuilding and ship-repairs. They have occupied the lower end of the spectrum by offering to be ship-breaking yards. The undersea resources are not being exploited in a sustainable manner in the absence of a regulatory framework. The extra-regional powers are having a free run-in term of exploiting the undersea domain for resources and multiple other blue economic returns. Lack of big investments and minimal application of high-end science & technology tools has ensured unviable and unsustainable ways of undersea exploration and exploitation. The fragmented geopolitics does not allow the nations in the region to come together in any way to build mega initiatives. The demographic bulge in the region is not getting channelised into constructive nation building activities. This leads to youth getting vested into non-productive and at times even into anti-national activities. [16, 17]

The security bogey has become a major curse for the region. The spending on the security forces has become a significant drain into the national economy. The lack of indigenous Research & Development (R&D) in the tropical littoral waters with unique characteristics has meant over-dependence on the imported military hardware at very high cost and minimal effectiveness on ground. The brute force method of maintaining high numbers in terms of human resources and other assets among the security forces with minimal induction of the modern systems is no match to the disruptive and emerging technology means being deployed by the non-state actors. We have already had multiple incidents in the past where major attacks have been launched from the sea route and more recently the drone attack in an Air Force base is the manifestation of the larger asymmetry that exists and complete shift from the conventional rules of engagement. Low Intensity Conflict (LIC) is the order of the day and is only likely to get stealthier with higher element of surprise [4, 12].

The fragmented approach among the stakeholders and turf wars among the policy makers is a sure recipe for disaster. The consolidation on all fronts is a problem and thus, the capacity and capability building remain a low priority. In the absence of consolidation, we will always be short of resources for S&T (write full form of S&T) and local site-specific R&D. Every stakeholder is spending significant amount of resources and effort in building their own infrastructure and that is never enough to match up to the real requirements on the ground [18].

Underwater Domain Awareness Framework

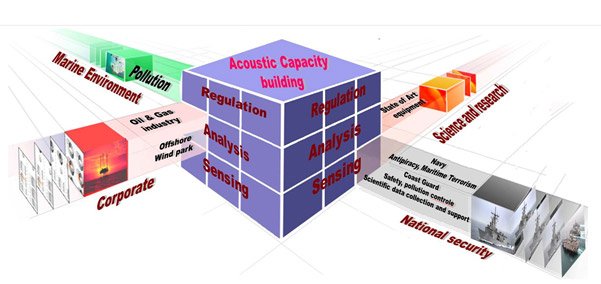

The concept of Underwater Domain Awareness (UDA) in a more specific sense will translate to our eagerness to know what is happening in the undersea realm of our maritime areas. This keenness for undersea awareness from the security perspective means defending our Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC), coastal waters and varied maritime assets against the proliferation of submarines and mine capabilities intended to limit the access to the seas and littoral waters. However, just the military requirement may not be the only motivation to generate undersea domain awareness. The earth’s undersea geophysical activities have a lot of relevance to the wellbeing of humankind and monitoring of such activities could provide vital clues to minimise the impact of devastating natural calamities. The commercial activities in the undersea realm need precise inputs on the availability of resources to be able to effectively and efficiently explore and exploit them for economic gains. The regulators on the other hand need to know the pattern of exploitation to manage a sustainable plan. With so much of activities, commercial and military, there is significant impact on the environment. Any conservation initiative needs to precisely estimate the habitat degradation and species vulnerability caused by these activities and assess the ecosystem status. The scientific and the research community needs to engage and continuously update our knowledge and access of the multiple aspects of the undersea domain. Fig. 2, presents a comprehensive perspective of the UDA framework. The underlying requirement for all the stakeholders is to know the developments in the undersea domain, make sense out of these developments and then respond effectively and efficiently to them before they take shape of an event.

Fig. 2 Comprehensive Perspective of Undersea Domain Awareness

The UDA framework on a comprehensive scale needs to be understood in its horizontal and vertical construct. The horizontal construct would be the resource availability in terms of technology, infrastructure, capability and capacity specific to the stakeholders or otherwise. The stakeholders represented by the four faces of the cube will have their specific requirements, however the core will remain the acoustic capacity and capability. The vertical construct is the hierarchy of establishing a comprehensive UDA. The first level or the ground level would be the sensing of the undersea domain for threats, resources and activities. The second level would be making sense of the data generated to plan security strategies, conservation plans and resource utilisation plans. The next level would be to formulate and monitor regulatory framework at the local, national and global level.

Figure 2 gives a comprehensive way forward for the stakeholders to engage and interact. The individual cubes represent specific aspects that need to be addressed. The User-Academia-Industry partnership can be seamlessly formulated based on the user requirement, academic inputs and the industry interface represented by the specific cube. It will enable more focused approach and well-defined interactive framework. Given the appropriate impetus, the UDA framework can address multiple challenges being faced by the nation today. Meaningful engagement of young India for nation building is probably the most critical aspect that deserves attention. Multi-disciplinary and multi-functional entities can interact and contribute to seamlessly synergise their efforts towards a larger national goal.

Acoustic Capacity & Capability Building

The acoustic means are the only way to generate domain awareness in the undersea region. The acoustic capacity and capability building pertains to managing the challenges and opportunities of the tropical littoral waters. The cold waters in the temperate and polar regions ensured that the sound axis (axis of minimal sound speed) was at shallow depths (as low as 50 m near the pole). This meant that the acoustic propagation remained concentrated around this sound axis, thereby ensuring minimal interaction with the surface and the bottom of the sea. On the contrary, the depth of sound axis in the tropical littoral waters is in the range of 1500 m (compared to the 100 m in the temperate region), thus there is significant interaction of the acoustic propagation with the two boundaries. This is one reason why littoral is a term used along with tropical in warm waters. The high interaction with the surface and the bottom means a severe degradation in the signal quality and high uncertainty in sonar performance. The high biodiversity in the tropical waters also ensures higher attenuation on the acoustic signal during propagation. The diurnal and seasonal variation in the underwater parameters further adds to the fluctuations in the acoustic propagation characteristics [19, 4].

The only way to minimise uncertainties in sonar performance is to build acoustic models that can predict underwater channel behaviour based on environmental parameters. These models will have to be validated across varying sea conditions and also across varying applications. The typical system for any domain awareness consisting of to see, to understand and to share, holds good here as well; however, the connotations may vary [20, 21].

To see includes the sensors that will gather information across the entire EEZ and beyond. The underwater sensors and their capabilities to see far, will be a major concern. The vast area cannot be mapped by conventional sensors alone. In any case, initiating a massive security exercise to deploy sensors is impractical, resource wise, and also may not go down well with the regional sensitivities, diplomatically. We will have to deploy strategies that are able to collect data from all possible seagoing vessels or enterprises and integrate it to the data centre. Environmental and academic research is a very potent means to camouflage security missions. We require platforms that will deploy the sensors at appropriate locations to adequately sense the region and collect the data for further analysis. These platforms could be surface or sub-surface that can reach the location along with the sensor and minimal interference from their own operations. Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) could be more cost-effective for a large-scale UDA initiative. Even static sensor suite could be deployed for data collection for long durations. A mix of Commercially-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) equipment for data collection and also specific prototype design of sensor and data acquisition systems may have to be developed to be installed across static and dynamic platforms to map the entire area.

To understand or analysis is a critical component that may be able to overcome some of the deficiencies of data collection. The analysis could be centralised or distributed based on the resource availability and strategy deployed for data acquisition. The first concern would be to minimise underwater channel distortions from the received data and also ensuring data integrity by verifying the corruption and errors. Deep learning methods are available today that can manage multiple data sets and provide the big picture. Also, High Performance Computing (HPC) infrastructure will be required to manage the Big Data in real time. The advanced underwater acoustics and signal processing may be deployed at the centralised facility or the distributed nodes.

The stakeholders may be integrated to this entire programme in a very covert manner to tap their data collection into the big infrastructure. The smart programme being implemented is a very unique model for this purpose. All kinds of data collection will seamlessly get channelised into the central systems with safeguards for data privacy for the individual users and metadata will be available for security analysis and policy formulation. Digital India already addresses many of the issues related to digital data and its handling. Digital Ocean should be our national priority.

To share or the networking of the systems for seamless data and information flow from source and destination to the central system is a critical component. The real time processing and networking is the key for any meaningful impact. The networking in the RF domain has progressed sufficiently to meet the requirement. The sensor networks have to be configured to bring the underwater signals above water to take advantage of the advances in RF. The old fashioned SOSUS systems (Sound Surveillance System) and the likes are thing of the past and need to evolve into their modern forms like DRAPES. We have to work on a very innovative model that is a mix of DRAPE (Deep Reconnaissance And Prevention of Emergencies) Systems and others, keeping in mind the tropical littoral issues and also the high traffic density in the IOR [22].

Way Ahead

The broad UDA framework needs to be dissected into individual S&T areas that have relevance across multiple sectors and applications. In this section we try to present few such areas that are representative to the vast UDA framework across the marine and the freshwater systems.

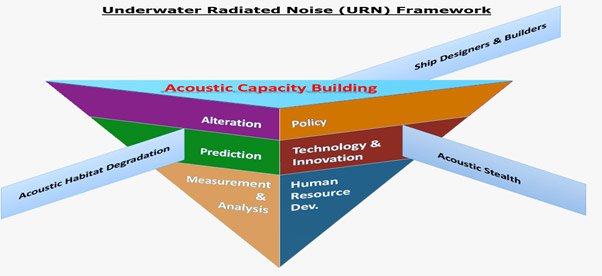

Underwater Radiated Noise (URN) Management is one of the most critical areas across military and non-military applications. The increasing shipping traffic across varied sectors starting from cargo in the high seas to coastal and inland waterways has huge impact on the underwater acoustic characteristics. The radiated noise from the marine vessels generates low frequency sound that overwhelms the low frequency spectrum of the ambient noise in the water bodies. The low frequency noise suffers minimum attenuation in the underwater domain so has significant impact over thousands of kilometres. Any underwater deployment of sonars for surveillance or marine mammal monitoring gets severely degraded due to poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Acoustic stealth for military deployment of platforms and acoustic habitat degradation for marine mammal conservation requires effective URN management. The shipbuilding and ship repair also needs to take note of the URN management aspects and deliver ships with requisite URN levels. Opportunities in this domain exist from URN measure & analysis to prediction and deception/alteration. Given the size of the shipping fleet in the merchant marine and the naval warships, this is a huge area available for technology as well as policy intervention. Acoustic capacity & capability building has innumerable dimensions as seen in Figure-3, which presents multiple aspects of the URN management and also brings all the stakeholders together in a seamless manner [23].

Fig. 3 Underwater Radiated Noise (URN) Framework

Sediment Management is another major opportunity for significant military and non-military applications. The broad areas of concern are freshwater resource management, flood control, navigation for inland water transport, port management, deployment of military vehicles in water bodies and more. There is significant military requirement in terms of logistics and movement of military assets across water bodies. Maintaining safe navigation and all-weather access across these water bodies could be a major challenge. There has been significant focus on port-led growth under the Sagarmala initiative and also the multimodal connectivity across waterways. These require massive acoustic capacity and capability building to ensure uninterrupted operations in our waterbodies.

Sediment management originates from prediction and prevention of the siltation process, de-siltation and also disposal of the silt. The tropical littoral waters have very high flow which causes high siltation. De-siltation needs to be done in a scientific manner to ensure viability of the projects. The acoustic survey and sediment classification is the key to the entire process. The volume of silt is a huge challenge from the perspective of removal and disposal. The dredging has multiple options with varying cost based on the nature of the silt. The disposal of the silt has become an impediment given the logistics cost and also non-availability of dumping ground. Precise sediment classification can ensure economic viability of the entire de-siltation process. There is significant wealth in the silt and with proper sediment management, this could turn out into a waste to wealth story. Figure-4, presents the multiple aspects of the sediment management framework. The stakeholders can seamlessly synergise and pool their resources to manage this effectively. The policy and technology interventions can be managed efficiently with enhanced acoustic capacity and capability building for sediment management [24].

Fig. 4 Sediment Management Framework

Aquaculture and Digital Oceans. The aquaculture industry in India has significant potential as a blue economy opportunity. The tropical littoral waters are known breeding grounds for shrimp farming and given the high value of shrimps in the global market, it a huge opportunity. However, shrimp farming is a high-risk venture due to disease outbreaks, environmental fluctuations, lack of scientific awareness and more. The small farmers are unable to sustain this venture, in the absence of financial support from the insurance companies and also banks. The unorganised sectors have a challenge to grow due to inadequate policy support from the governments as well. India, with a coastline of over 7,500 km, has a massive opportunity to build this industry and help the community to engage in productive ventures. Digital oceans is the only way forward to develop deeper understanding of the underwater conditions and fluctuations. Once we understand the patterns, the uncertainties of the environment and the production outputs could be minimised with better interventions. The lower uncertainties and enhanced predictability of the entire process will encourage participation of the financial entities to support such sectors. The policy and technology interventions for enhanced and sustainable aquaculture is a major requirement. India has failed to take advantage of its vast tropical littoral waters due to lack of prioritising of the digital ocean initiative. The acoustic capacity and capability building is again a key requirement for Digital Ocean, and if managed well could be a significant export opportunity of the Skill India initiative [25].

There is a substantial strategic angle to shrimp habitats and generating deeper understanding of their soundscape. They are known to be the loudest of the creatures with vocalisation ranging beyond 200 dB ref 1 μPa at 1 m. Even the biggest mammal on earth, the blue whale vocalisation is of the order of 196 dB ref 1 μPa at 1 m. The whales are in few numbers (in single digits) in a group, whereas the shrimps are in millions in a shrimp bed. There have been incidents in the past when a submarine has been acoustically swamped due to snapping shrimp vocalisation. The Indo-Pacific region is going to be a major maritime theatre for submarine deployment. The nations within have also acquired strategic submarines and Underwater Domain Awareness (UDA) for submarine deployment requires no emphasis. There are multiple other aspects of UDA that need to be prioritised for strategic security purposes ranging from maritime intelligence against undersea intrusions, effective deployment of subsea vehicles, mitigating the sub-optimal sonar performance to more demand high priority in the ongoing geopolitical and geo-strategic developments.

Conclusion

The high-end technology developments globally have taken place during the Cold War period. Even the underwater technology developments have largely taken place as part of the super-power rivalry. The Americans and the Russians have deployed huge resources to generate better understanding of the undersea domain for ensuring enhanced sonar performance. However, the engagement during the Cold War period were in the temperate and polar regions. The Cold War had different geopolitical and geo-strategic realities. Military spending was not questioned and military projects did not require any environmental clearances as well. The post-Cold War era has completely different political scenario. Even in the US and other democracies, the leaders have to balance socio-economic requirements along with national security requirements. The environmental clearances cannot be bypassed for national security projects. Pooling of resources and synergising of efforts across the stakeholders is the only way ahead. Geo-economics has taken the high ground and geopolitics has to match the economic growth engine trajectory.

The tropical littoral challenges and opportunities have to be driven by S&T and site-specific R&D. This requires high infrastructure investments and long-term commitment to develop the know-how. User-Industry-Academia partnership is inescapable. All the stakeholders have to be committed on a long-term basis to this model. Beyond the nations, the regional frameworks will make more sense and also keep the extra-regional powers at bay. The fragmented stakeholder interactions within the nations and also in the region is a major impediment to ensuring higher synergy. Digital Oceans driven by the UDA framework can be a game changer. It will be a paradigm shift for ensuring safe, secure, sustainable growth for all in the Indo-Pacific region.

India has taken multiple steps to build maritime infrastructure and the SAGAR vision demonstrates significant seriousness on the part of the Government of India. A User-Academia-Industry partnership model is presented in figure-5, for realising the Digital Ocean dream. It binds together multiple announcements from the Government of India and also the stakeholders both in the marine and the freshwater systems.

Fig. 5 User-Academia-Industry Partnership for the UDA Framework

Figure-5, brings all the core R&D domains on one side of the funnel and the government initiatives on the other, to provide the three main pillars of the UDA framework. The effective policy intervention, innovative technology support and the acoustic capacity & capability all seamlessly will come together across the stakeholders. The UDA framework proposed by the MRC has significant merit for a whole of nation approach. The above User-Academic-Industry interface can be implemented on ground with the setting up of a Centre of Excellence to build on all the five major requirements of research, academia, skilling, incubation and policy. The details of the COE is attached in Enclosure-1. (Where is Enclosure 1)

The SAGAR vision of the Prime Minister is better served by effective realisation of the UDA framework in a comprehensive manner. China is aggressively trying to make inroads into the IOR and to counter them will not be easy. The Whole-of-Nation Approach is extremely critical given the geo-political and geo-strategic realities. Beginning with the IOR and then the Indo-Pacific region will require the support of UDA framework. India can play a leadership role in the region and ensure that the extra-regional powers are kept away with enhanced S&T superiority and local site-specific R&D.

Author Brief Bio: Dr(Cdr) Arnab Das is Founder & Director, Maritime Research Centre (MRC), Pune

References

[1] “Confluence of the Two Seas”, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan. August 22, 2007. Speech by H.E. Mr. Shinzo Abe, Prime Minister of Japan at the Parliament of the Republic of India. Available at https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html.

[2] https://thediplomat.com/tag/quadrilateral-security-dialogue/.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pacific#/media/File:Indo-Pacific_biogeographic_region_map-en.png.

[4] Arnab Das and D.S.P. Varma, “Ocean Governance in the Indian Ocean Region – An Alternate Perspective”, Maritime Affairs, 2015, pp. 1–19.

[5] http://indiafoundation.in/sagar-indias-vision-for-the-indian-ocean-region/.

[6] Blog Post by Alyssa Ayres, from Asia Unbound: A Few Thoughts on Narendra Modi’s Shangri-La Dialogue Speech, June 1, 2018. Available at https://www.cfr.org/blog/few-thoughts-narendra-modis-shangri-la-dialogue-speech.

[7]https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/document_publication/Indian%20Ocean%20Region_v6(1).pdf

[9] Joseph L. Nimmich and Dana A. Goward, Maritime Domain Awareness: The Key to Maritime Security, International Law Studies – Vol 83, Global Legal Challenges: Command of the Commons, Strategic Communications and Natural Disasters, Edited by Michael D. Carsten, 2007. Available at https://www.usnwc.edu/Research—Gaming/International-Law/New-International-Law-Studies-(Blue-Book)-Series/International-Law-Blue-Book-Articles.aspx?Volume=83.

[10] “Amendments to the International Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue (IAMSAR) Manual”. International Maritime Organization. MSC.1/Circ.1367 24 May 2010. Available at http://www.imo.org/blast/blastDataHelper.asp?data_id=29093&filename=1367.pdf.

[11] Cdr Steven C. Boraz, U.S. Navy, “Maritime Domain Awareness

Myths and Realities”, Naval War College Review, Summer 2009, Vol. 62, No. 3.

[12] Arnab Das (2016), “Impact of Maritime Security Policies on the Marine

Ecosystem”, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 12:2, 89-98.

[13] Arnab Das, “Marine Eco-Concern and its Impact on the Indian Maritime Strategy”, Chapter 5, MRC Press Feb 2017.

[14] Sarabjeet Singh Parmar, “Maritime Security in the Indian Ocean A Changing Kaleidoscope”, Journal of Defence Studies, Vol. 7, No. 4, October–December 2013, pp. 11–26.

[15] Alok Bansal (2010) Maritime Threat Perceptions: Non-State Actors in the Indian Ocean Region, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 6:1, 10-27.

[16] SHARACHCHANDRA M. Lele, “Sustainable Development: A Critical Review”, World Development, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 607-621, 1991.

[17] Joris Larik et al., “Blue Growth and Sustainable Development in Indian Ocean Governance,” The Hague Institute for Global Justice Policy Brief, 2017.

[18] Dr. P. K. Ghosh & Sripathy Narayan, “Maritime Capacity of India: Strengths and Challenges” Observer Research Foundation. Available at https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Maritime Capacity_of_India.pdf.

[19] Paul C Etter, “Underwater Acoustic Modelling and Simulation”, Fourth Edition, CRC Press, 2013, Taylor and Francis Group.

[20] Arnab Das, “Marine Eco-concern and its Impact on the Indian Maritime Strategy,” Journal of Defence Studies, Vol 8, No. 2, Apr 2014.

[21] Arnab Das, “New Perspective for Oceanographic Studies in the Indian Ocean Region,” Journal of Defence Studies, Vol 8, No. 1, Jan 2014.

[22] Steven Stashwick, “US Navy Upgrading Undersea Sub-Detecting Sensor Network”, The Diplomat, November 04, 2016. Available at https://thediplomat.com/2016/11/us-navy-upgrading-undersea-sub-detecting-sensor-network/.

[23] Arnab Das (2019) Underwater radiated noise: A new perspective in the Indian Ocean region, Maritime Affairs: Journal of the National Maritime Foundation of India, 15:1, 65-77, DOI: 10.1080/09733159.2019.1625225.

[24]https://mrc.foundationforuda.in/documents/researchNotes/Interns/Report%20on%20Sediment%20Management%20Framework%20for%20Tropical%20Littoral%20Waters.pdf

[25]https://mrc.foundationforuda.in/documents/researchNotes/Interns/APY%20Analysis%20for%20Shrimp%20Farming.pdf

Very well written article addressing the larger picture!!!