Introduction

The return of President Trump to a second term ushered in a wave of sweeping tariff declarations, reigniting a global trade war that involved both allies and adversaries of the United States, ultimately plunging the world economy into a pronounced and far-reaching recession (Bouët, Sall & Zheng, 2024). These announcements, rolled out in successive stages, culminated in April with the imposition of reciprocal tariffs, prompting varied retaliatory responses from affected trading partners. The administration defended these unilateral tariff measures as necessary to address its persistent trade deficit with certain countries, blaming the imbalance on unfair trade practices. Central to its complaints were discriminatory tariffs, ongoing IPR infringements, and regulatory hurdles that hindered US exports and widened the trade deficit. Such tariffs may have briefly boosted customs revenues, but their broader implications cast doubt on the effectiveness of these measures. While some rationale supported the retaliatory approach adopted by the Trump 2.0 regime, the administration’s stance appeared unilateral. It contravened the spirit and rules of the multilateral trading system established in WTO agreements (Klingebiel & Baumann, 2024). The tariff increases were mainly a coercive tactic, aimed at pressuring trade partners into negotiations to rebalance trade relations and create a fairer playing field.

Through this, the US aimed to reduce its deficit by establishing bilateral or regional trade agreements. However, the core issue behind the imbalance was America’s unchecked domestic consumption. Without curbing domestic demand, its trade deficit was likely to continue. Instead of implementing structural reforms domestically, the Trump administration chose a populist strategy, shifting the burden of adjustment onto external trade policy. Additionally, the method used to set reciprocal tariffs was questionable, as these were often tied to the trade deficit levels rather than the extent of protectionism practised by partner countries. To strengthen its protectionist stance, the US employed or planned to use existing domestic laws, such as IEEPA, Sections 338, 301, 232, and 122, to restrict trade with specific partner countries, products, and regions. By June 2025, the heated rhetoric of the trade war began to ease, with negotiations resuming on various bilateral and multilateral platforms. How the international community responds to this changing tariff landscape remains an open question.

India, facing an average tariff of 26% on its exports, has not been immune to the consequences. To avoid a direct tariff clash, India has actively pursued economic agreements such as the ‘India–U.S. COMPACT’ and ‘Mission 500’ to strengthen bilateral trade relations. These initiatives cover both goods and services and seek to balance the trade relationship through mutual agreements. The US will benefit from market access in high-technology sectors, while India is given greater entry into labour-intensive segments. The long-term effects of these arrangements deserve careful examination, especially considering the unilateral imposition of a 26% reciprocal tariff by the US and India’s actions regarding US tariff policies.

Tariff Tremors: Global Response

The ‘America First Policy’ took centre stage during President Trump’s 2015 election campaign and has since remained a symbol of his political vision (Bukhari et al, 2025). It was the cornerstone of his first and second presidential terms, guiding the administration’s domestic and international stance. At its core, the policy aimed to revitalise domestic production—particularly in the manufacturing sector—to boost employment and to adopt a cautious approach towards regional integration. A key focus of the agenda was to pressure major trading partners into revising their trade frameworks to align with US efforts to narrow its growing global trade deficit. The policy’s operational focus involved strengthening the US influence over multilateral institutions such as the WTO and various UN bodies—including the WHO—alongside strategic use of tariff threats, withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord, and a confrontational stance on immigration. However, this assertive nationalist approach has weakened the United States’ leadership in various areas of global collective action—ranging from climate change to multilateral trade—and has strained its economic relations with longstanding allies like the European Union, Canada, and Mexico, as well as strategic rivals such as China.

The initial course of action involved the sudden and comprehensive imposition of tariffs on several trading partners, aimed at reducing the growing bilateral and overall trade deficit of the United States. The US chose a unilateral approach in trade policy, trying to rebalance its bilateral trade gaps with key economic partners. These policy measures mainly aimed to protect the domestic manufacturing industry, prioritising aluminium, steel, and the automobile sectors. A significant factor contributing to the decline in US exports was widespread violations of intellectual property rights, often justified under the guise of ‘unfair trade’ practices. Other countries also saw similar practices, including forced technology transfers, non-transparent subsidies, and other structural distortions. These ongoing imbalances led President Trump to implement extraordinary policy measures designed to shift the trade balance in favour of the US and to address persistent bilateral deficits with certain nations.

Following the Executive Order issued on 20 January 2025, tariffs in various formats continued to be implemented until May of the same year. Due to their extensive scope and scale, only a few key tariff decisions are highlighted here for illustration. In January 2025, tariffs were significantly increased on imports from China, Mexico, and Canada—including steel—with Canada and Mexico facing 25% tariffs (10% on energy), and China facing 20%, justified by concerns over fentanyl trafficking and border security. In March, imports from Canada again faced a 25% tariff, with energy imports specifically taxed at 10%. A blanket tariff of 25% was also imposed on countries importing crude oil from Venezuela. Tariffs on steel and aluminium were designed to encourage the relocation of base metal manufacturing back to US territory. By April, the administration announced broad reciprocal tariffs affecting over 90 trading partners worldwide. Tariffs against China increased to 84% and 125%, before a 10% reduction was granted following the Geneva Accord. Steel and aluminium tariffs rose to 50% in May, establishing the US as the most tariff-protected economy in the industrialised world. The average tariff rate in the US rose from 2.5% in January to 27% in April, eventually decreasing to 15.6% in June after some reversals were announced.

Diverging Trade Deficit

The United States’ trade deficit with the rest of the world is a deeply rooted structural issue that cannot be solved simply by imposing trade restrictions. As a consumption-driven economy with a per capita income reaching $82,000 in 2023, the US shows a strong preference for imported goods, especially finished consumer products, which is a key reason for its growing trade deficit. The US dollar, the world’s reserve currency, remains in high demand worldwide, leading to a persistent appreciation that worsens the trade imbalance. This upward pressure on the currency makes imports more attractive while exports become less competitive, weakening the global position of American manufacturing. Recognising these structural inefficiencies, many U.S.-based companies have chosen to move their production overseas, unintentionally increasing pressure on the country’s external sector.

Additionally, global trade regimes have played a significant role in shaping the US’s external trade performance. During the second wave of the global recession, especially in 2017, the US economy saw a partial recovery, with exports and imports expanding compared to the previous global trade environment. However, this recovery was accompanied by an increase in the overall trade deficit, driven mainly by a resurgence in goods trade.

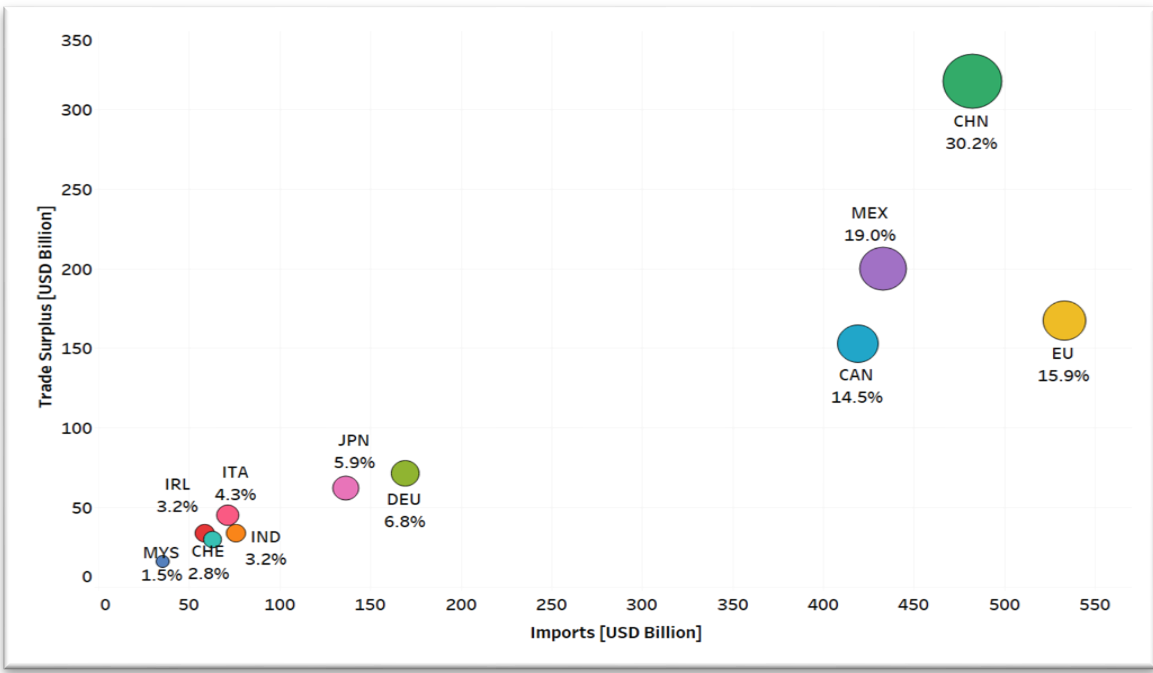

Figure 1: America’s Trade Gaps: Top Contributors by Country- Share in Overall U.S. Deficit, %

Source: RIS (2025)

The growing deficit in goods was partly offset by a favourable trade balance in the services sector, providing some relief. Nevertheless, the ongoing imbalance in goods trade negatively affected the current account and added to the gradual depletion of foreign exchange reserves. It is worth noting that the US external sector performed better in 2023 compared to 2022. In analysing the trade deficit, China emerged as the largest contributor, accounting for 30% of the total US trade gap, as shown in Figure 1, with a bilateral deficit of $317.7 billion in 2023. The US has also voiced concerns over its NAFTA partners, although bilateral trade flows—especially with Canada—have been more favourable than with other major trading partners. Bilateral trade tends to increase when the trade deficit ratio is low.

While the US showed lower bilateral trade deficit ratios as a proportion of total trade with Canada and Mexico (22.3% and 30.0%, respectively), countries such as China (49.1%), Italy (46.2%), and Ireland (40.7%) exhibited significantly higher proportions. Empirical analysis indicates that the US has struggled to sustain its global competitiveness in specific sectors, failing to maintain a consistent advantage across its major trading partners. Conversely, India recorded a relatively modest trade surplus of $33.8 billion with the US in 2023, representing 28.7% of bilateral trade. India recorded surpluses in agriculture and manufacturing while incurring deficits in minerals, along with signs of intra-industry trade in 2023 (RIS, 2025). The Indian trade surplus with the US appears to be structural, distributed across a broad range of sectors at the product level. Therefore, attempts to rectify this bilateral trade imbalance through tariff manipulation are unlikely to produce meaningful results.

Reciprocal Tariffs and Reconciliation

Reciprocal tariffs were implemented by the United States on 2 April 2025, with a comprehensive 10% tariff applied universally, alongside country-specific rates tailored to mirror the tariff structures of each trading partner. The Trump Administration targeted nearly 57 nations, notably exempting other NAFTA members from its scope. For several key partners—China, India, Japan, and others—tariff rates were determined based on various criteria, including existing tariff systems, bilateral trade imbalances, currency policies, etc. Unlike the uniform MFN tariffs approved by the WTO, these reciprocal tariffs varied significantly—China faced over 34%, Vietnam 46%, Thailand 36%, Japan 24%, and South Korea 25%. This policy also included India, with a 26% tariff levied on its exports. The impact was particularly felt in electronics, auto components, aluminium, and steel sectors, while industries like pharmaceuticals and energy exports were relatively exempt.

In response, some nations resorted to direct retaliation—China imposed 25–30% duties on soybeans, semiconductors, and automobiles, while the EU responded with tariffs of up to 25% on selected American goods such as whisky, motorcycles, jeans, and orange juice. India and others adopted more targeted strategies, penalising US exports like almonds, apples, walnuts, and pulses; Brazil notably reduced soybean shipments to China, undermining American trade interests. Others imposed non-tariff barriers—South Korea limited meat and poultry imports, while Japan introduced strict chemical compliance protocols for manufactured goods. Meanwhile, the US pursued a more conciliatory approach towards countries like Canada, Mexico, and Vietnam, opting for diplomatic negotiations and tailored bilateral agreements. By June, the Trump administration, aiming to de-escalate the growing trade conflict, stepped back from aggressive tariffs and pursued dialogue-based resolutions through bilateral deals. These agreements took various forms, involving strategic partners such as China, the EU, the UK, and South Korea. At the G7 Summit, the US and Canada committed to developing a new trade framework before July 2025—an approach India, notably, did not remain distant from.

Decoding Policy Impacts on India

Export advantage for India: A Structural Issue

India has consistently maintained a trade surplus with the United States — a crucial dynamic for a country that usually runs a persistent trade deficit with the rest of the world. With an ambitious export target of $2 trillion by 2030, India has aligned its ambitions with the Indo-US’ Mission 500′ initiative, which aims to increase bilateral trade to $500 billion by the decade’s end. This initiative fits well with India’s broader economic vision of becoming a $7 trillion economy by 2030. However, the path to this milestone is hindered by the current average tariff of 27% on Indian exports to the US. This barrier might impede India’s competitive ability to reach its export targets, especially with lower-cost exporters such as China.

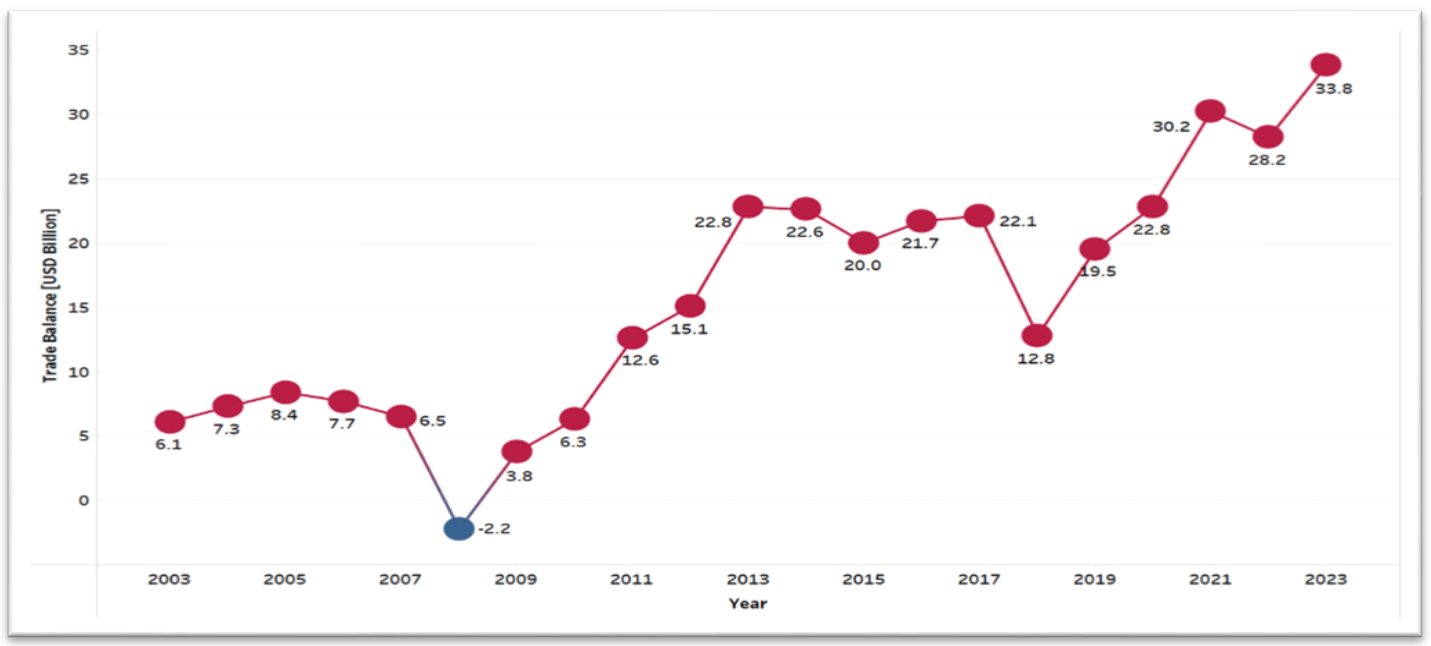

India has consistently been a competitive exporter to the United States across both primary and secondary sectors. Generally, India has maintained a trade surplus in agriculture and manufacturing, while the US has held an advantage in the mineral trade. Despite India’s significant and persistent trade deficit in hydrocarbons, its overall trade balance with the US remained favourable over the past twenty years, except for 2008, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Exporting Advantage: India’s Surplus Story with the US, $Bn

Source: RIS (2025)

This favourable balance remained steady during global economic growth, fluctuating modestly between $6.1 and $7.7 billion from 2003–07, before rising sharply from $3.8 billion in 2009 to $22.8 billion in 2013. Between 2014 and 2017, India’s trade surplus plateaued once again before experiencing a steep decline in 2018. The period from 2019 to 2023 marked another phase of rapid and consistent growth in India’s trade surplus, briefly interrupted by mild stagnation in 2022. Empirical evidence shows India’s strength in specific agricultural sub-sectors such as animal products, fruits and vegetables, and processed foods, while the US demonstrated competitiveness in oils and fats. In manufacturing, India recorded notable surpluses in chemicals (particularly pharmaceuticals), textiles and clothing, gems and jewellery, and machinery.

In 2023, India’s mineral imports amounted to $13.5 billion, yet a bilateral trade deficit of only $6.8 billion was recorded—an outcome attributed to intra-industry trade (IIT) within the same sector. Nonetheless, China remains a significant competitor for India in several product lines across the US market. Against President Trump’s 2.0 aggressive tariff regime, analysing at the product level across key target trade partners—Canada, China, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Mexico—indicates that higher tariffs on China may spill over, indirectly impacting Indian exports. While these tariffs could restrict China’s access to the US market, India may not be able to fill the resulting gap across numerous product categories without initiating renewed negotiations under the umbrella of ‘Mission 500’.

Structural Trade Issue

The Trump administration remained convinced that India’s trade surplus in manufacturing and related sectors was a short-term anomaly, manageable through firm tariff-based strategies. The persistent bilateral trade deficit with India was not seen as a systemic economic issue and could be addressed using conventional tariffs or regulatory tools. As an emerging economy, India was often expected to export raw materials and import manufactured goods. However, this longstanding assumption does not hold in the case of Indo-US trade relations. Contrary to expectations, India does not export a significant volume of primary goods to the United States, while the US, in contrast, exports substantial amounts of such goods, especially minerals, to India. The U.S. has effectively become a net exporter of primary commodities to India. In 2023, India’s bilateral trade in intermediate goods with the US was valued at $52.6 billion, from a total bilateral trade volume of $117.8 billion. Within the intermediate goods sector, semi-processed products dominated, accounting for 68.8% of bilateral trade in this category. Although parts and components (P&C) comprised a relatively small part of this trade, India was expected to increase its dependence on the US for such imports. Nonetheless, India managed to sustain a trade surplus in semi-processed goods and the P&C sub-segments of intermediate trade.

As India progresses in its industrialisation, it is logical for its reliance to shift towards imports of final capital goods, ideally evident through increased bilateral trade volumes in this sector. However, that expected trend has not materialised. Furthermore, India’s most significant bilateral export segment remains final consumer goods, which has generated the highest trade surplus. This segment alone contributed a surplus of $23.7 billion out of the total $33.8 billion bilateral trade surplus recorded in 2023. The final consumer goods sector has thus become the primary source of India’s export earnings from the American market. It accounted for 66.7% of India’s final goods exports and 25% of the bilateral trade volume between the two nations.

Nevertheless, this heavy dependence on final consumer goods has become a strategic weakness for India. Within this category, Indian exports have shown a high concentration of a limited number of products. Specifically, just 44 products made up over 70% of India’s exportable items within the final consumer goods segment. These concentrated exports include processed foods, cotton & textiles, fish products, pharmaceuticals, footwear, carpets, and fresh produce. Such over-reliance could restrict diversification and resilience against policy shocks. Therefore, upcoming trade negotiations with the US should focus on securing stable and long-term market access for these key product lines.

Bilateral Arrangement: Mission 500

In February 2025, both nations launched ‘Mission 500’, a Multi-sector Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) to boost economic and technological cooperation. The BTA covers trade in goods and services, establishing a solid and future-oriented economic partnership. ‘Mission 500’ aims to double current bilateral trade flows in goods and services to reach a target of $500 billion by 2030. A core element of the agreement is a reciprocal framework, where the US seeks to improve access for its industrial products in India. At the same time, India aims for preferential terms for exporting labour-intensive goods to the U.S. India has long maintained trade surpluses in agro-based, low-technology, medium-technology, and even high-technology goods, reflecting its growing export capabilities across various sectors. Historically, the US has maintained high tariffs on low-technology goods; reducing these tariffs could help expand India’s access to the American market. The signing of ‘Mission 500’ and the India-U.S. COMPACT represents a significant development in bilateral relations. Under the BTA, India is expected to increase its imports of US goods and services, which will likely help balance the US’s persistent trade deficit with India. However, implementing high reciprocal tariffs could seriously challenge achieving the goals and cooperative spirit of ‘Mission 500’.

Conclusion

The second Trump administration’s tariff regime cast a long shadow, sowing pessimism among both allies and rivals of the United States. In its first five months, the administration unleashed a surge of bilateral and global tariffs as a bold assertion of its ‘America First’ doctrine. However, by June 2025, these tariffs were scaled back following negotiations with key trading partners. The cascade of tariff declarations from Washington prompted varied retaliation from affected nations. While major partners such as China and the European Union responded in kind with mirror tariffs as before, others employed more measured counterstrategies to navigate the pressure from the US’s unrelenting tariff offensive (Yu, 2020; Li, Balistreri, & Zhang, 2020). Adopting a more moderate stance, India chose to absorb the 27% reciprocal tariff while entering into negotiations that led to the India-U.S. COMPACT and the launch of ‘Mission 500’ in February 2025.

As such, India maintained a trade surplus of $33.8 billion with the US in 2023, supported by robust agricultural and manufacturing exports. Besides the primary sector, India has consistently recorded trade surpluses across multiple industries. Its strength particularly lies in exporting semi-processed goods and finished consumer products to the US market. Under the ‘Mission 500’ terms, both nations agreed to double their current trade volume in goods and services, aiming to reach a milestone of $500 billion by 2030. The agreement envisages reciprocal market access—India in labour-intensive goods, and the US in industrial sectors, especially high-tech products. India continues to post surpluses across low-, medium-, and high-technology sectors, even as the US imposes especially steep tariffs on low-tech imports. The American commitment under ‘Mission 500’ to reduce tariffs on labour-intensive goods could boost India’s future exports in this sector. However, the long-term success of ‘Mission 500’ depends on how effectively both sides manage future trade negotiations amid current high tariff tensions.

Author Brief Bio: Prof. S. K. Mohanty is a Professor at the Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS), New Delhi.

References

Bouët, A., Sall, L. M., & Zheng, Y. (2024). Trump 2.0 Tariffs: What Cost for the World Economy? Policy Brief, 49.

Bukhari, S. R. H., Jalal, S. U., Ali, M., Haq, I. U., & Irshad, A. U. R. B. (2025). America First 2.0: Assessing the Global Implications of Donald Trump’s Second Term. Qlantic Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 6(1), 51-63.

Klingebiel, S., & Baumann, M. O. (2024). Trump 2.0 in times of political upheaval. Implications of a possible second presidency for international politics and Europe.

Li, M., Balistreri, E. J., & Zhang, W. (2020). The US–China trade war: Tariff data and general equilibrium analysis. Journal of Asian Economics, 69, 101216.

RIS (2025), Trump’s Trade Policies Peril Global Economic Stability, Research and Information System for Developing Countries, New Delhi.

Yu, M. (2020). China-US trade war and trade talk. Berlin, Germany: Springer.