16-17 September, 2021 | Virtual

Event Report

The Girmitiya Conference 2021 was conducted virtually with the support of the Overseas Indian Affairs (OIA-II) Division of the Ministry of External Affairs, on 16-17 Sep. 2021. The conference’s overarching theme was ‘Changing identities, shifting trends, and roles’. Over the two days 38 speakers and over 70 participants debated and discussed the issues, contributions, successes and tribulations of girmitiyas across the world focusing on their history, identity formation, cultural preservation, and their evolving relationship with India. This was perhaps the first conference that brought together Indian descendants from 18 countries and provided a voice for them to express their views.

Inaugural:

83 participants

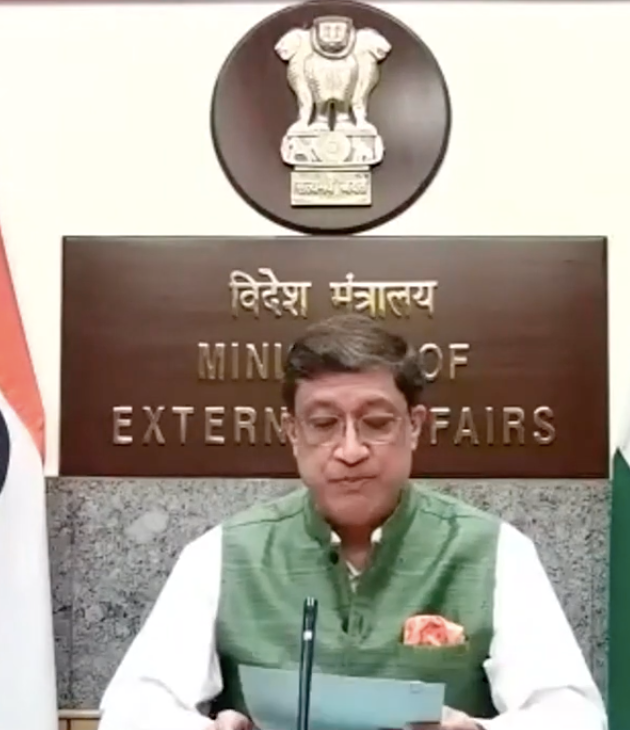

Shri V Muraleedharan, MoS External Affairs, India

Shri Muraleedharan welcomed the audience to the Girmitiya Conference 2021. He briefly highlighted the history of indentureship, the hardship faced by the the girmitiyas and the successes of their descendants today. He commended their maintenance of ties with India, their affection towards Indian customs, traditions and language. He also mentioned that their efforts and contribution to society in their home countries has not gone unrecognised as many of these countries celebrate them through the declaration of a public holiday or day. He then highlighted how India engages with the diaspora through the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas and many such other programmes. He concluded by wishing the conference success. The text to his speech is available here.

Hon Mrs Kalpana Devi Koonjoo-Shah, Minister for Gender Equality and Family Welfare, Mauritius

Hon Mrs Konjoo-Shah, a granddaughter of indentured labourers herself, said that the conference is important. She informed the gathering that her father was a Minister and a Member of Parliament, that she spoke in Bhojpuri at home, and that despite the success of her father she comes from humble belongings. She shared a brief history of indentureship to Mauritius and of sugar plantations, the right to go back to India being discouraged and the formation of Indian communities in her country. She explained that initially migrants had come from Pondicherry but in the later years they were brought from the Bhojpuri belt. The first migrants had entered Mauritius on 1 August 1834, and this wave would swell after the abolishment of slavery. She addressed themes like what makes you Mauritian? Who is a girmitiya? How did the term come to be? Finally, she explained the role that Indians have played in shaping Mauritius – either through the socialist model that Mauritius is based upon or through the many ways in celebrates Indian festivals. She said that as Mauritius is comprised on 60% Indians, their contribution and efforts do not go missed. She ended by her speech by reading out a moving poem by your forefathers written in Hindi about their time in Mauritius and their longing for their motherland, India.

Session 1: Making of the Girmit (Indentured) Diaspora

100 participants

Dr Bhugwan Singh, Head of Department of Surgery at the University of KwaZulu-Natal

The first slaves to South Africa came from India, largely from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, which Henry Pollack in his books goes to great detail in outlining. Dr Singh mentioned that Indians were isolated yet had to complete with the elite society. Despite all these hardships, Indians thrived. Indian merchants were treated as British Indians and enjoyed a better status than indentured Indians. He also quoted Chinua Achebe and said ‘lions need their own historians’, implying that Indians need to write their own history. Dr Singh in his presentation showed documents – a colonial number, a British India Passport (which the merchant class had access to, and thereby affording them great mobility and a head start) – the only documents to prove your identity and claim your Indian-ness. He then spoke about apartheid in Africa and claimed that Natal, where he lives, has faced much racism. He concluded by saying that the legacy of anti-Indian racism was legislated (disenfranchising Indians, restricting ownership of land and restricting migration to India) and that representations made to girmitiyas were rhetorical.

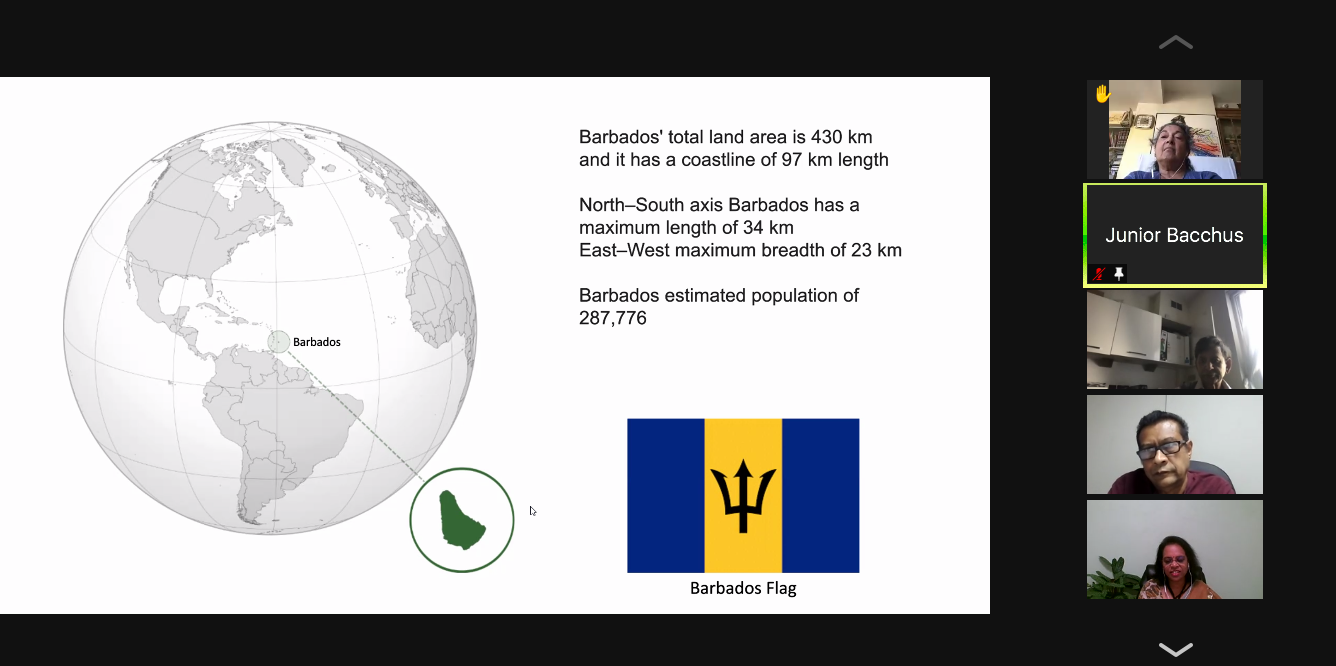

Junior Bacchus, Honorary Consul of India to St Vincent and the Grenadines

Following the abolishment of slavery, estate owners in St Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG) needed to find cheap labour. The year was 1845 and the Portugese and Chinese were first brought to SVG. They could not survive the conditions and many were dying. After giving a brief history, Mr Bacchus threw light on the fact that landowners did not treat Indians well. Around 1862 there was racism in the island, which led to riots. Yet, Indians who came to did a lot of good – many set up businesses, became doctors and lawyers, and traded across the island. Slowly, the population of Indians grew to 7000. The first Indian to become a Member of Parliament was Morgan in 1951. He pointed out that many Indians are choosing to migrate from SVG to the US, and their population is dwindling. Yet those who remain continue to be successful business people. Indians prefer to be entrepreneurs rather than work for a boss. In 2006, Mr Bacchus formed the Indian Heritage Foundation to bring together the energies and aspirations of the Indian community. He worked to officially recognise the Indian community through Indians days that are celebrated today. He shared a message that the Prime Minister of SVG shared with the Indian Heritage Foundation and recognised the efforts and contributions of Indians, calling them a “magnificent part” of the society.

Dr Kumar Mahabir, Anthropologist, University of Guyana

Dr Mahabir focused his presentation on a unique and often unspoken aspect on indenture – that of military migrants during indentureship: from the battlefields of India to the cane-fields of Guyana. He deconstructed the myth that not all migrants who came to the West Indies were unskilled. He began by giving an overview of the Sepoy Revolt in India, which the British claimed was largely unsuccessful. This mutiny took place at the middle of the indenture period. Through his presentation he tries to understand if some of the ex-soldiers of the Revolt legitimately migrated or secretly escaped to the West Indies in order to flee persecution for mutiny? He tapped into the memories of some of the descendants of these soldiers, as well as looked at literature.

The Revolt was sparked by Mangal Pandey and Rani Lakshmi-Bai of Jhansi. Dr Mahabir showed the audience a clip from Mangal Pandey. He estimates that 20,000 sepoys migrated to the West Indies, and elaborated on how he arrived at the figure. There was in fact a mutiny on board the ship to Guyana, and documents show that 23 to 30 men on the ship “possessed evidence of military training” and that their identity was carefully concealed. It is interesting to note that most of them are from Awadh. On another ship there were records of sepoys as well, and a Guyana newspaper carried a headline – ‘The Sepoys Have Come’. Most of them had to hide so they changed their name and downgraded their cast so that they could run away to these islands. It is for these reasons that Guyana became a hotspot of indentureship and the headquarters of the police in the West Indies. He also provides evidence of women warriors in Guyana, and links it to repeating the attack of Rani Lakshmi-Bai of Jhansi against British armed forces in Uttar Pradesh in 1857.

Session 2: Keeping Indian Culture Alive

85 participants

Appasamy Murugaiyan, Research Officer, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, France

Mr Murugaiyan spoke about indenture labourers in francophone countries and highlighted an important difference: in British colonies assimilation was never practiced while in Francophone countries assimilation was a general rule, either through language or through the conversion to Catholicism. The important take away here is that Indians lost their cultural identity in francophone countries. Importantly, 85% of descendants in francophone countries are of South Indian descendant – mainly Tamilian and Telugu. Mr Murugaiyan tries to understand how indentured labourers keep their language and culture alive despite the process of assimilation. Every diasporic community chooses identity markers and redefines them based on the emerging realities of its environment. Indian descendants face a challenge in that they have to pick between being Indian or identifying with a regional culture like Tamil, Telugu etc. Many descendants, Mr Murugaiyan claims, do not speak Tamil for example but still feel deeply for that culture. He took the audience through this research where he identifies 12 criteria of culture. In Malaysia and Singapore all 12 criteria are present and therefore have a direct relation to the preservation and transfer of culture where it can felt strongly. However, in Mauritius, Reunion, Martinique and Guadeloupe the number of visible criteria reduces and therefore the presence of Indian culture too is dwindling.

Deoroop Teemal, HSS Trinidad and Tobago

Mr Teemal focused his presentation on Trinidad and Tobago. He gave a few facts on the demographics of Trinidad and revealed that the Hindu population in Trinidad will face a decline if not actively preserved. He said Indian movies had a major impact on Indian culture. Some people among the community were attracted toward Creole culture, and a few others migrated or converted to other religions. By the 1950s Hindi was being taught in schools, and religious pujas were performed in Sanskrit. Bhojpuri and other local languages soon lost their relevance, despite some efforts in reviving them by locals. Indian cuisine remains the major aspect of Indian culture, such as paratha, curry, sabzi, kheer, laddoo and street food such as ‘doubles’. Doubles has perhaps become a national dish in Trinidad and Tobago! In terms of religion, he said temples and mosques are present across the island and Diwali has been declared a national holiday in the country. The Ram Leela tradition is very much alive and is performed in many villages in the islands. Other traditions have unfortunately died. Bollywood music has been very popular although it did to some extent kill local music, particularly Bhojpuri music. Since the declaration of the International Day of Yoga, there has been a revived interest in the practice of yoga and Ayurveda as well. The major challenge in keeping Indian culture alive is in maintaining cultural identity. The politics of the country has a major role to play particularly since the 1950s when ethnic politics has become popular. Since Trinidad’s independence, Indian culture was never a part of the national cultural scene, which favoured African cultural norms. This made saving and keeping Indian culture alive in the islands very difficult. Since 2000-2015 there has been a slight shift in Trinidad to accept Indian culture more, although there is a lot more to be done to recognise Indian culture.

Padma Mythili Nanduri, Director NSKB Aneasthesiology Services Inc, Barbados

Ms Nanduri began her presentation by describing her own journey to Barbados and went on to give a brief historical background of the country. Barbados will become a Republic in November this year. She pointed out that unlike in many other islands, it was not necessary to bring indentured labourers from India. However, Barbados saw an influx of Guyanese and Trinidadians who came on their own will. There is a Hindu temple built in 1997 where all deities are kept to worship and were brought from Mumbai. Most Hindus do puja regularly and follow Hindu festivals like Holi, but are unable to preform all rituals on a larger scale due to restrictions placed in Barbados. On Sunday’s it is common for Indians to congregate at the mandir, follow strict Indian dress codes, perform puja, sing bhajans, learn tabla, and eat Indian food to keep their identity alive – this is despite many of them probably not even knowing where India is. The feeling of being Indian is that strong! She also elaborated that Indians do a lot of charity in Barbados. She said this is the same even with Indian Muslims in the country, who migrated from the Gujarat region.

Ashook Ramsaran, President Indian Diaspora Council Int’l, USA

Mr Ramsaran gave a brief background of the indenture system and showed pictures of the ships that brought Indians to the various islands, as well as the various documents they brought along with them. He mentioned second journeys to the UK, US, France, The Netherlands and other destinations. He mentioned that most descendants of indentured labourers were able to keep their culture intact, perhaps because of the distance and the longing to connect with India in any way possible – through masala, through respecting parents and elders, from celebrating festivals, and watching movies. He mentioned that Indian Embassies and the ICCR help in preserving the culture, particularly Hindi. Indians he believes learn to easily adapt and assimilate within societies helping them to achieve great success.

Session 3: Girmitiyas and India

75 participants

Dr Kirk Meighoo, Public Relations Officer, United National Congress, Trinidad and Tobago

Dr Meighoo spoke on ‘Girmitiyas and India: A Complex Relationship in Constant Flux”. He began by asking, are girmitiyas Indian? At what point do you lose your connection with the ancestral country? In his case, he has not, despite being the sixth generation Indian in Trinidad. There are small populations in countries like St Lucia and Belize where Indian culture is mostly lost. In Trinidad however, many Indians feel they are Indian despite others (post-1947 Indian migrants to Trinidad) making them feel like they are not. He says if we consider India as a collection of different cultural practices, then Trinidians Indians are very much a part of the Indic being. Trinidan Indians have built Indian villages in Trinidad, they don’t speak the language but have built authentic Indian villages. He said their consciousness has developed differently because the pre-partition culture is very much alive in girmitiya countries. His own perspective is that his roti and dal may not be the same but it is still authentically Indian.

What is girmitiyas relationship to India? He said most Indians are not aware that Indians live in Trinidad! And within the global context of slavery, indentureship is a minor part of history. He however, believes that this migration is central to world history. If the East India Company was the most powerful then this part of history must be important too. At independence however, there was an unfortunate move by Nehru. When asked about the situation of Indians abroad, Nehru declared that they have to decide whether they are Indian or nationals of those countries. Indians in Trinidad looked to protection from the Indian government, which was not reciprocated. This abandonment defined the relationship of girmitiyas and India. He pointed that Indian consciousness is somehow seen as racist and undermining and this prevents some Indian descendants from getting close to India. The same is not felt by Africans – they are free to feel as African as they wish to be.

He ended his presentation by comparing NRIs versus PIOs and feels that the Indian Government pays more attention to NRIs, despite PIOs being more connected to the Indic consciousness.

Ravi Dev, HSS Guyana

Mr Dev mentions that the past is not dead and this seen through features in Guyana. What is the called the coloniality of powers takes three forms – systems of hierarchy, systems of knowledge and conscious systems from which India and the ex-colonised world is still trying to extricate itself from. The most popular among these are race, where the white race is put on top. The feeling of Caucasian-ness needs to go if one wants an equal society. One must not forget that it was Indian capital that was used to build the colonies!

He said that interestingly girmitiyas disappeared from Indian national consciousness after the end of indentureship. Very few movies and academic papers in India work on the topic of girmitiyas. Indian politics also neglected girmitiyas and eventually, India became a mythical land and not a homeland. Girmitiya lands saw the second migration of Indians, reducing girmitiyas to minorities in the girmit countries.

He spoke about the rise of the BJP in India and the importance the government gave to Indian descendants. In particular, he acknowledged the role of late Sushma Swaraj ji in bringing girmitiyas to India and to experience the country. However, girmitiyas asked, ‘what is in it for us?’ He said it is time for India to define who is bharatiya or India. Maybe India should learn from the recently concluded African-CARICOM. Girmitiyas need to be granted a special relationship with India, rather than a second place platform, for all that the community does in maintaining ties with India and keeping its culture alive. Why did India (Bharat) not condemn the rigging of elections in Guyana? He said it disappointed the community by not doing so.

He ended his presentation by giving some recommendations: Bharat has to reciprocate what girmitiyas have done for India; there has to be a quid pro quo and Bharat needs to defend the needs and wants of girmitiyas; India today, does not have the respect of former African colonies because they ignored the security dilemma of local girmitiyas; NRI Indians do not socialise with girmitiya Indians and speak disparagingly of them – they view it as a village culture and ICCR should address this.

Vikash Ramdonee, Acting Rector, Royal College Curepipe, Mauritius

Mr Ramdonee began with his own family history of being a descendant of a girmitiya – he is the son of a farmer who was brought to Mauritius to convert soil to gold. The unique factor that distinguishes the Indian diaspora from the rest is that Indians are hard working. From the Mauritius perspective, India has protected the diaspora. However, it is time for the diaspora now to exert themselves globally. He asked: how can the diaspora help India? He suggests perhaps we should move away from this narrative and asks – how can the diaspora help each other? The diaspora has the responsibility to support other diaspora and should begin to focus on business, economy and development. It is perhaps time to stop romanticising India and look to the girmitiya community to build relationships.

Gabriel Pate, Retired Public Officer, Belize

Mr Pate is a third generation East Indian. His grandparents came to Belize in the last half of the 19th Century. Belize is the only English speaking in the region, and gained independence in 1981. Indians account for 3.5% of the population of Belize. Between 1851-1870 there was a large migration of East Indians to Jamaica. The story of the arrival and survival of East Indians however, is linked to the American Civil War. It was then that 100s of East Indians, called coolies, were brought to work in the cane fields and sugar mills of Southern Belize. India became a faint and distant memory to the East Indians. Indians lost their culture and took up English surnames like Williams, Pate, Jacobs. Most experts believe, from the remnants of the language that remains, early East Indians spoke Bhojpuri.

The East Indian contribution to the growth of Belize has not been acknowledged. Indians are only looked at as dark skinned people. The major problem facing East Indians in Belize today is intermarriage. Only about 5% of East Indians marry within their ethnic group, as about 50% of Indians are related to each other in Belize, given the small numbers. He predicts that in the next two generations, Indians (culture) will cease to exist in the country. Post-independent migrants from India to Belize, like the Sindhis, do not interact with East Indians.

East Indians pioneered the opening of Southern Belize in the 1960s, the military produced two former commanders of Indian descendants, many Indians are teachers in the primary and secondary schools, they are a major force in Methodist churches, they own bus companies, they account for 40% of mechanised rice production in Belize, and they have produced two government ministers over the past eight years. For a population of only 3.5%, Indian descendants have performed very well.

To maintain unity among the East Indians of Belize, Mr Pate established the East Indian Council. Through the Council he hopes to keep Indian culture alive. East Indians cannot loose their culture to another, cannot become a shadow to assimilation. He ended by quoting the Mexican Ambassador who visited Belize and said “you can take an Indian out of India, but you cannot take India out of an India”. Finally, he shared a moving poem he wrote titled “Kaala Paani”.

DAY 2

Session 1: The Burden of History

61 participants

Dr Kamala Lakshmi Naiker, Senior Lecturer, University of Fiji

Dr Naiker began her presentation by giving a short history of the migration of Indians to Fiji with the first ship – Leonidas. Between 1879-1960, some 60,000 indentures arrived in Fiji. For indentured labourers, life as a girmit was hopeless and full of uncertainty. She says there are two common tools in writing history that Fijians have used – the use of language, and constructing narratives. They have used the language of the coloniser and not Hindi to communicate their struggles to the wider world. This is the first burden. Writers have been trying to make their narratives as real as possible. The history of indenture from the beginning was that of suffering. Over the years, the girmit has contributed to nation building in India. She ended her presentation by saying that there is no doubt that the burden of history is felt (both in Fiji as being outsiders, and in India as being rejects), but one must celebrate the successes of the Indian descendants as well. She was sad that the Indian diaspora was forgotten after independence.

Karen Dipnaraine-Saroop, Activist, USA

Ms Dipnaraine-Saroop spoke on the ‘Resistance, Resilience and Perseverance: A Case Study of Trinidad and Tobago’. She noted that 85% of migrants to Trinidad from India were Hindus and relied on their own memories to preserve Indian culture. Indians were regarded as strange and unwelcome intruders by the western influenced African inhabitants. The governing administration did not pay attention to the education of Indian children because the government believed they would return to India. Eventually, they sent their children to missionary schools and could become a teacher only if they converted to Christianity. Interestingly, many did not want to convert to Christianity as they wanted to preserve their ancient faith. It was only in 1982 that Hindu schools were allowed. She highlighted how politics, economic oppression, proselytization, and race tensions presented challenges to keeping Indian culture alive. During this time, a transformation was happening within the Hindu community, who began to celebrate Diwali on a large scale. These celebrations brought different Hindu sects under one umbrella and introduced the Indian community to other communities in Trinidad. Mr Dipnaraine-Saroop took the audience on a journey through Trinidad and described how politics, economic oppression and race tensions presented challenges to keeping Indian culture alive.

Dr Nalini Moodley-Diar, Executive Dean, Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa

Dr Moodley-Diar focused her presentation on memory, identity and heritage through a visual or art history background. South Africa is a deeply divided society along the lines of race, language and gender, undermining any sense of tolerance and unity. As recently as August 2021 there were riots with chants “one Indian, one bullet”. She explored the works of Alka Dass, who uses stitching on doilies to thread together heritage and layers of memories. Patriarchy adds another layer of burden of history among Indian South Africans and their experiences in domesticity. She also looks at the work of Sharlene Khan who explores the many women who committed suicide as the only way to get out of their problems, in her work ‘Drowning Durgas’. Her portrayal of Reshma Chhiba of women’s backs show the transformation of Indian women in South Africa and how they deal with their Indianness – from conservatism to modernism.

Session 2: Voices from the Indian Diaspora

70 participants

Anand Jayrajh, Attorney, South Africa

Mr Jayrajh mentioned that labour, slavery and indenture can be spoken of in the same breath and proceeded to give a brief history of indenture. Voices from the diaspora articulate both positives and negatives like discrimination, typecasting and racism. As the negatives have often been spoken about, Mr Jayrajh focused on the positives – the progress they have made, their hard work, dedication, and their will to succeed. In South Africa, the diaspora finds itself in a situation where they themselves have become a victim on their own successes. Emphasis on education, although important, is not the only common thread among Indian diaspora communities. He also highlighted the social cohesion programme of the South African government.

Ajay Chhabra, CEO Nukhut, UK

Mr Chhabra delivered a personal account of the work that his organisation, NutKhut does, as well as his journey of discovering Fiji through some objects he had collected from his grandparents. He traced his roots from Madhya Pradesh, and described his grandparents journey to Fiji from thumb print to stepping on Fijian soil. He spoke about his role as an actor and his quest for discovering his girmit identity and in preserving it. He also spoke about the work he does to highlight girmit experiences across the world.

Daljeet Maharaj, Secretary Fiji Hindu Society, Fiji

Mr Maharaj is a third generation descendant of an indentured labourer. He briefly described his family’s journey to Fiji from India. He visited India for the first time in 2017 under the the Know India Programme and discovered Indian descendants from other countries as well. He said girmitiyas are also known as jahajis in Fiji and were brought on 87 ships that transported 60,000 Indians including Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Indians brought with them Hindi, Telugu and Tamil, built temples, mosques and gurudwaras. Due to differences in dialects it went on to become Fiji-Hindi. He spoke about the work that the Fiji Hindu Society does and shared photos of the festivals celebrated, the chanting of mantras, and the acceptance of Indian culture by natives. He highlighted the achievements of Indians in Fiji – from producing a President, to soccer players and leaders in the culture sphere. He ended his presentation by talking about the challenges that Indo-Fijians face – from coups and insecurity, living in the informal sector, to preserving culture and sanskars and the ability to afford a decent living.

Session 3: Making of the Girmit (Indentured) Diaspora

57 participants

Virendra Gupta, Former Ambassador

Shri Virendra Gupta began his presentation by mentioning that India’s relationship with diaspora and vice versa wasn’t the same as before, like it is at present. It has evolved over some time. He highlighted three distinct aspects of diaspora i.e. the diaspora in the Gulf, the diaspora in developed countries, and the third is the Girmitiya diaspora. The Girmitiya diaspora’s feeling of warmth and attachment to India is unmatched as compared to the other two groups. Despite living very far away the Girmityas have been the most emotionally attached to India. He spoke in length about the movement of the Girmitiyas and how they were dispatched. Such hardships created a sense of brotherhood and solidarity amongst the Girmitiyas. This helped in creating a sense of a new identity. A very strong factor that held them together was their religion. The Girmityas believed and referred strongly to Ramayana and Hanuman Chalisa. Though they held very strongly to the Hindu identity the caste distinction faded when they moved to a new region, and religion indeed became a strong glue to bind them. Lastly, he recommended the role of the Indian diaspora community especially the Girmit community should be highlighted more when one talks about India’s soft power.

Ruben Gowricharn, Professor, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Dr Gowricharn focused his talk on girmitiya peasants. He filled the gap in literature on the evolution of the diaspora, particularly the transformation of girmitiyas from labourers to business or other fields. What are the distinguishing characteristics of the diaspora? For one they all belong to India, they formed ethnic communities, took their strong sense of religion and identity with them. They formed nascent labour communities on plantations and generally mixed to high degrees except for North and South India division. Suriname was the only country that had only North Indians so the division between North and South Indians was not felt. Women were a minority in all societies but played an important role. In Suriname access to land was practically unlimited as the planters went bankrupt. Indians in Fiji on the other hand had no access to land. He also spoke about the impact of Indian cinemas on the diaspora community. His main argument is that multiple homelands were developed due to migration, mixing of people, English (or local language) education.

Manoranjan Mohanty, Associate Professor, University of the South Pacific, Fiji

Dr Mohanty focused his presentation on Indians in Fiji and pointed out that Indians who arrived in Fiji were very diverse. They came from across India and spoke many languages from Tamil, Telugu and Hindi. Fiji was created as a casteless society and labourers gradually transformed from being bonded labourers to small farm holders. The diaspora was also diverse in terms on religion – Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs had migrated to Fiji. Over time, within Fiji, newer diaspora groups emerged such as the Tamil diaspora who created a space of their own. Architecture in temples also resemble these newer diaspora groups. Dr Mohanty mentioned that languages like Malayalam and Kannada have been lost.

Session 4: Keeping Indian Culture Alive

56 participants

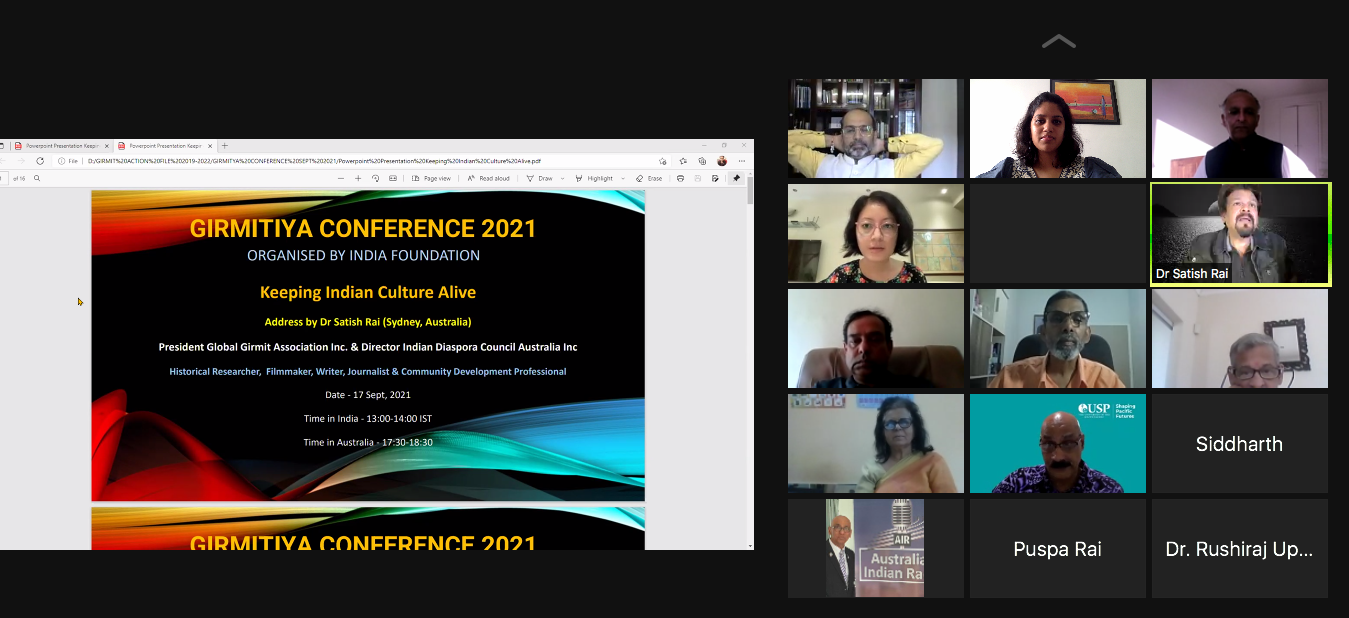

Satish Rai , Director Raivision Films, Australia

Dr Rai shared his experience of tracing his roots to India and was able to visit some of the places his four grandparents are from. He informed the audience that he made a film on girmitiyas in 2019. Mr Rai believes that we can have multiples homes and identities and need not be restricted to one. He considers his Janambhumi to be Fiji, his Karmabhumi as Australia, and Matrabhumi as India. He finds his connection to India very strong as his ancestors belong to the country, and contents most from the diaspora feel the same way. In Fiji, the parents played a very important role in passing on their culture to their children. This is especially true in preserving languages like Bhojpuri and Awadhi that ICCR does not help preserve to as much an extent as Hindi. He mentioned that these languages are losing their popularity to Hindi. He also spoke about the role that religion, folk songs, festivals, wedding rituals and cuisine have played in keeping Indian culture alive.

Selwa Nandan, Secretary of Fiji Girmit Council, Fiji

Mr Nandan focused his presentation on what the Fiji Girmit Multicultural Centre is doing to preserve Indian culture. They have built schools and temples for which they had to make tremendous sacrifices. For that, the present generation is forever indebted to them. He said it is this that ties the present generation to their ancestors and therefore India. The Centre provides training to students at a nominal cost in language and dance among other aspects of Indian culture. Despite the ICCR suspending the support to the centre, it is still continuing and is the largest cultural centre in Fiji. He then spoke about the challenges that the centre is facing (many which were compounded by Covid-19) and the main being external funding.

Sarita Boodhoo, Chairperson of Bhojpuri Speaking Union, Mauritius

Dr Boodhoo began her presentation by singing a song from India’s first generation migrants to Mauritius. Indians have taken with them their culture no matter where they went. The first 36 girmitiyas came to Mauritius from Chota Nagpur and this created a community in Mauritius. Today, every Hindu family in Mauritius has a Tulsi plant in front of their homes and celebrate their Indian-ness with a lot of pride. There are many institutes in Mauritius that have been set up to promote Indian research and culture. In Mauritius, 27 Bhojpuri channels exist, and the joint family system still exists although it is slowly being replaced by a single family unit. She mentioned that dal, saag, katchori, biryani and mithai are the staple food, and that Bihar’s dal puri has become a fast food in Mauritius. She also mentioned that in Mauritius the Girmitiya Arrival Day is celebrated as a national holiday, as is Holi and Diwali. Most Indian villages in Mauritius have mandirs, a neem tree under which stories of Ramayana are told. The names of the descendants themselves are a testament to the fact that Indian culture is alive. Villages and towns in Mauritius are named after Indian villages and cities. Finally, she mentioned that folk songs have been declared as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO.

Session 5: Girmitiyas and India

60 participants

Pt Bhuwan Dutt, Pandit, Fiji

Pt Dutt began his presentation by giving a history of India and gave a brief history of the arrival of Indians in Fiji. He asked how many Indians in Fiji returned to India, and how many times has India enquired about the wellbeing of Indians in Fiji. He said that women were not spared on their arrival in these new lands and that bulk of the revenue from the farms fuelled British development. How have these workers been compensated? Thousands of workers lost a permanent connection to India. It is the duty of Indians to look after Indians. He ended is presentation by quoting from the Rig Veda.

Pt Dhunsanker Maharaj, Pandit, South Africa

Pt Maharaj mentioned that talking about girmitiyas is both painful and uplifting at the same. Painful because of the history associated with indenture and the hardships that were endured. Uplifting, because of the courage, determination and resilience that the indentured showed. South Africa as a society has been through tremendous hardship be it racism, segregation or apartheid. Indians had to remind the black South African that Indians had built hundreds of schools and conducted many sewa projects in black townships. This reminded them that Indians are driven by race. Pt Maharaj views the conference as keeping the girmitiya consciousness alive. He said that if you visit South Africa you will notice that Indian culture is thriving. There has also been a longing to connect with India as they viewed it as their motherland and call it Bharat Mata. South African Indians visit India regularly either to visit ashrams, temples, for shopping etc. The problem South Africa faced was that they did not have local Indian schools but instead had to attend Western, Christian schools. Because they were not given the opportunity to learn their history or the opportunity to learn their language, they were robbed of their heritage. Unfortunately, South African schools taught Indians that the White Man was perfect and superior. Therefore, the problem of conversion is also alive. Why is this a problem? Because slowly Indian customs are lost – the emotional bond with India gets lost, social habits change, clothing styles change, food habits change. They are Indians only by looks and eventually abandon their Indian-ness.

Dr Pavitranand Ramhota, Former Officer-in-Charge of Rabindranath Tagore Institute, Mauritius

Dr Ramhota made an important point in that despite the hardships faced by the indentured in Mauritius, there were elements of joy that was the consequence of by being Indian. Marriage for instance, became a high point not just for the marrying couple but also for the community as marriage was accompanied by celebration, song and dance. During marriage, the pundit performs ceremonial functions for the couple but today they are being adapted to suit the changing societies. The best example is that marriage is nowadays solemnised on weekends to ensure that family and friends can participate. The haldi (turmeric) ceremony today is followed by song and dance. In India turmeric is first applied to the feet, however in Mauritius it is first applied to the forehand and feet last. In Mauritius, unlike in India, the birth of the girl child was always celebrated. Caste has come to represent popular discourses. In Mauritius caste is still adhered to in some respects – surnames have disappeared as the first name became the surname making it hard to trace the caste. Caste has not been academically debated or studied in Mauritius. There is fear in Mauritius that talking about caste is like opening a Pandora’s box. He concluded that Indo-Mauritius society has evolved differently from India.

Rajan Nazran, CEO Global India Series, UK

Mr Nazran runs the Global Indian Series to understand what identity means for Indians. The Series tries to understand what it means to be a Person of Indian Origin (PIO) and has learnt that as a community we are often neglected despite all the work and contributions we have made. He briefly highlighted the work that the Global Indian Series has done in brining to the forefront the riots in South Africa against the Indian community in August 2021.

Session 6: Voices From the Indian Diaspora

54 participants

Dr Akshai Mansingh, Dean of Faculty of Sports, University of West Indies, Jamaica

Dr Mansingh’s presentation was visual and he was able to show the audience pictures from his own family’s archives and their journey to Jamaica. He showed the audience a photo of the Ramayana that was taken to Jamaica but was written in Urdu. Through these objects, Indian culture was kept alive. Indians in Jamaica have contributed to the national cuisine through curry, roti. In North Jamaica, Indian jewellery can be found and this was pedalled as a cottage industry from plantation to plantation. Indians engaged in rice cultivation and were active in cricket, perhaps even bringing it to Jamaica. The state denied religion and persecuted Indians by not allowing education and denying health. So much so that in Trinidad a temple had to be built on the sea to circumvent the ban on temples on land. For 400 years Trinidadian Indians were cut off from India – except for when the cricket team would visit West Indies. Interestingly the Indians in the West Indies would root for India and not West Indies! Many Indians who visited or studied in West Indies would belittle local Indians and look down upon them. Indians from India thought they were “cooler” than the local Indians. Today, Indian culture is seen during graduation ceremonies when graduates where sarees, there are no “one day Christians”, Indians are educated, “everybody a smaddy”, chutney music are common. Today the culture is so strong that when an airport opened in Trinidad it was opened with a Hanuman puja and not by the Trinity Cross. Trinidad has seven local Hindi radio stations that are played across the West Indies. Indian Arrival Day is also celebrated in Trinidad with the cultural exposé being completely Trinidadian. The important thing now is get children involved. Interestingly instead of eating on banana leaves, Indians eat on lotus leaves! He cautioned that India has a literate and a growing middle class, and the population is shunning their own language and are looking down at traditional values and culture, family units are becoming decentralised and Indians are no longer proud of their culture. India is a lesson for the West Indies: there needs to be a cultural (re)explanation and (re)education if we Indian culture is to be kept alive, as opposed to only retaining Indian names.

Vishnu Bisram, Political Scientist and Journalist, Guyana

Mr Bisram stated that voices from the Diaspora are about celebration, mourning, of tragedy and of the relationship with mother India or mother Guyana or mother Trinidad. Many from the diaspora are now twice removed from India having migrated to other countries within the Caribbean – to the US, UK and Europe. Most of the voices share a common complaint – the neglect from the Government of India. Hindi is under threat in Fiji and there is very little emphasis on reviving the language or even the culture in these countries. There is nothing to bring the diaspora together via the media or the Indian government– nothing (no platform) to discuss their needs, achievements and challenges. In India there is not much being done to support the girmit diaspora. Engaging with the diaspora is viewed as a burden as it does not bring in much revenue, and is therefore neglected altogether. He said few people care about persevering Indian culture, and India does not seem to be bothered either. There is a paucity of scholars in the diaspora on India. Girmit academics do not get funding for their research. Scholars who do exist focus on their community (like Suriname, Fiji, etc), but very few have travelled far and wide and researched on the girmit community as a whole. There is no journal that focuses on girmits, although Mr Bisram, Mr Ramasaran and Mr Rai (all of whom spoke at this conference) are working hard to launch a journal next month. He said the voices of girmits are voices of disappointment in India – they expect India to do a lot more than what is being done. He suggested there can be regional offices, there can be regional programmes and conferences, yearly meetings in Delhi, meetings in girmit towns rather than in capital cities where girmits do not reside. Perhaps there could even be a think tank that focuses on girmits in India.

Shadel Nyack Compton, Managing Director, Belmont Estate Group of Companies, Grenada

Ms Compton shared her experiences as an Indo-Grenadian. She began by sharing her story of being raised in a household with strong Indian values. Despite studying in the US, she chose to return to Grenada and take care of her farm, which was bought by her grandparents. Her estate celebrates Indian Arrival Day, hosted a museum that showcased India, and tries to replicate pickles from India. 2.2% of Grenada’s population is Indian, 13.3% of whom are of mixed descent. The St George’s University markets heavily to Indian students and lecturers so Grenada is seeing a new wave of Indian migrants. The first Indians arrived in 1857 – 85% remained in Grenada while others migrated to other countries, mostly to Trinidad. A de-cultural programme forced Indians to abandon their culture and religion. Grenada’s small size did not allow Indians to establish an authentic community like seen in Trinidad, Guyana etc. Post indenture, the Indian community really struggled to retain a strong cultural identity. However, they attained significant positions in agriculture, politics, business etc.

What Indian values do we see today despite the degeneration of its culture and heritage? Families still try to hold on to the values, and there are pockets of communities that still live in extended families. The culture of thrift and hard work is evident. Dishes like dal, roti, curry, bhajji are all common dishes in Grenadian cuisine. Many plants like moringa, mango, tamarind, turmeric were brought to Grenada. Music and dance are some influences that Indians tend to hold on to. The most popular influence however is probably cricket.

How does Grenada celebrate India? Indian Arrival Day has been officially recognised as a holiday since 2017; Indian Independence Day and Republic Day are celebrated with the raising of the tricoloured flag; Holi and Paghwa are celebrated; a bust of Mahatma Gandhi stands tall; and Grenada sends young people to the KIP to experience India.

She then spoke about the work that the Indo-Grenadian Heritage Foundation, which she established, does to ensure that Indian culture is represented on the national landscape. India on its part set up an IT Centre, helped in some infrastructure development projects, there is some bilateral trade between the two countries (although there is much more room for this). In 2019 PM Modi pledged that CARICOM will receive a billion dollars from India.

Session 7: The Burden of History

59 participants

Shamshu Deen, Researcher National Archives, Trinidad and Tobago

Mr Deen first defined the the ‘burden of history’ as “demands of all humankind a level of responsibility”, and then went on to quote Rudyard Kipling, who in the white man’s burden said one must care for the conquered. He threw light on documents, general registers, estate registers etc. This is how Indian names entered the mainstream Diaspora country’s documentation. These are the databases that family historians look into to trace roots and help relieve the burden of history. He then spoke about how the diaspora can be connected and said the best way is to find family in India. He showed the audience documents of two brothers – one who went to Fiji and the other to Trinidad. These two people were brothers and came from Faizabad district from India and belonged to the Brahmin caste. The burden of history is so strong that brothers was displaced and unless family historians trace their roots the connections remain lost forever. But problems in tracing roots exist – recruiters wrote wrong information, wrong addresses were given, and some stories of the motherland written by ancestors were falsified or romanticised and cannot be traced to an existing place. In short, he said family history is very important as it helps track migration, satisfies curiosity, provides databases used for other disciplines like economics.

Maurits Hassankhan, Senior Lecturer, Aton de Kom University, Suriname

Mr Hassankhan identifies three burdens of history – identity, position of Indians in their respective home countries (countries of destination like Suriname), and the relation that the diaspora has with India. First, is identity. He asks, are we Indian? Are we Hindustani? Are we Surinamese? Migration to Suriname was from North India, particularly UP and Bihar who spoke Bhojpuri, Maithili, Awadhi etc. Very few were acquainted with Hindi. As people came from different areas, they developed a new language called Hindoostani towards the end of the 19th Century to communicate with each other. When indentured labourers finished their contract they organised themselves into communities and called themselves Hindoostanis, and objected to the usage of the term coolie. He mentioned that on signing the contract, the indentured labourer became a coolie for the European – the term was used for Indian coolies, Vietnamese coolies, Chinese coolies etc. At the end of indenture, they became agriculturalists and therefore objected to the usage of the term coolie.

Dr Baytoram Ramharack, Professor, Nassau Community College, Guyana

Dr Ramharack is a third generation Girmitiya from Guyana, whose grandfather originated from Allahabad and crossed the kala paani in 1930. The mentioned three things that he thinks are very crucial – having a girmitiya university, establishing a database, and the need for a commission of inquiry.

A girmitiya university is crucial to unburden the diaspora from their past. It will provide a place of learning. It will also give a chance for the girmitiyas to write their own history as opposed to the history written by the victor (as proposed by Winston Churchill). The second, is establishing a database like the Indenture Labour Route Project. Documents, archives and artefacts are in terrible condition today and need to be preserved. The third is a need to have a comprehensive commission on inquiry, not to extract monetary compensation from the colonials, but to document the history, something like is done with slavery.

He then narrated a story: Trinidad was born through the independence movement; the leading political party was trying to seek support from countries including from India and was led by Mr Vincent Mahabir. But, the conversation of who Mr Mahabir was never came up. When the government asked him if he is Indian, he replied saying that he is West Indian. In doing this, he misunderstood identity politics. Indians in Trinidad are sometimes confused about who they are.

Valedictory

63 participants

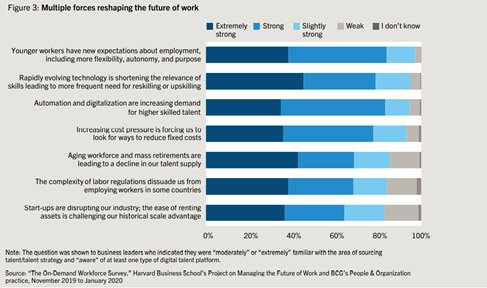

H.E. Mrs S. B. Hanoomanjee, High Commissioner of Mauritius to India

H.E Hanoomanjee thanked the organisers for the invitation to speak at the conference. She mentioned that the theme of the conference is very sensitive given that Mauritius is a land of migrants. Indians came as early as 1730 from Pondicherry and Chennai as settlers, but mass migration began only in 1834, following the abolition of slavery and the institutionalisation of indentured labour. This marked the sad journey of exile across the Indian Ocean. This time, most migration was from the Bhojpuri belt of India. when they migrated from the Bhojpuri belt of India. The recruiters of that time under British rule played their role in gyring away innocent indentured labourers who were the Girmitiyas. At that time, it was also an opportunity for the Girmitiyas to escape dire conditions of death and farming in India. However, given the high levels of illiteracy, many were misled about where they were departing for and the wages they would receive. This separation is one of the saddest chapters in human history. When the Girmitiyas reached their destination they were brought to work in sugarcane fields shouldering the burden of the economy of the British colony. They bear the burden of separation from their families and the indentured system was not based on a principle of equality and justice. Despite all the hardships they had to face the girmitiyas did not lose hope rather they persevered through blood, sweat, and tears. They contributed to what is today a prosperous Mauritius. The only great things girmitiyas brought with them when they came to Mauritius were their culture, tradition, art, and religion. They brought with them the sacred books of Ramayana and Bhagavad Gita. She noted that even the new generations of the Indian diaspora are actively upholding these values through socio-cultural groups. Mahatma Gandhi when he visited Mauritius in 1901 sowed the seeds of independence in the hearts of the indentured labourers. The descendants of Indian migrants played a crucial role in the emancipation and were largely instrumental in driving the liberation movement for our independence in 1968. Descendants of girmitiyas have come a long way. In the process of nation-building, there was no singular factor more important than the human capital for a small country like Mauritius. Mauritius has nurtured a close affinity with India both at the social and political levels. The High Commissioner paid special tribute to Prime Minister Modi for the highest respect given to the Indian diaspora by granting the status of Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) since January 2017. She also commended the Indian Government’s efforts in bringing people of Indian origin together by advocating the principle of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakum’ – The World Is One Family – and work together in advancing shared values and promoting security, stability and prosperity. Mrs. Hanoomanjee concluded on a very positive note that the diaspora can act as vital agents for development as all the countries gradually move into the knowledge economy, the smart economy, or in the wave of the fourth industrial revolution.

Shri Sanjay Bhattacharyya, Secretary CPV&OIA MEA, India

Mr Bhattacharyya described India’s migratory journey as a “rich history of amazing accomplishments and many adversities”. After giving a brief historical background of indenture and of their condition upon arrival on new lands, Mr Bhattacharyya pointed out that Indian culture was not lost. In fact, despite being many oceans away, Girmitiyas were “strong adherents” of Indian culture, giving them a unique identity today. He mentioned that Girmitiyas have played a significant role in enhancing the stature of India abroad and that they are a part of India’s soft power. The steady presence of Indian diaspora has even given rise to Indo-Caribbean, Indo-Mauritius, Indo-African, Indo-Fijian, and Indo-Malaysian populations – many of whom constitute the largest ethnic groups in some countries. Mr Bhattacharyya highlighted the role that the diaspora has played in shaping their host countries as well as in India through philanthropy, knowledge transfers, investments in innovation and in assisting with development projects. He also commended the hard work and perseverance of the diaspora that helped them hold the highest State and Government positions in the Girmitiya countries, serve in pivotal roles, run successful businesses and other enterprises. Mr Bhattacharyya stated that the Indian government values its extended family, it pays special attention to their needs, recognises their unique status and desire for links with India for which the Government launched the portal, Rishta, which is aimed at the diaspora. Mr Bhattacharyya also highlighted the various schemes and projects that the Government has for the diaspora like the Know India Programme, the Scholarship Programme for Diaspora Children, the Bharat Ko Janniye Quiz, and the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas. Mr Bhattacharyya concluded his address by saying that the Government works to advocate for the growth and benefit of the diaspora under the maxim of 4Cs – care, connect, celebrate and contribute. The entire speech may be read here.