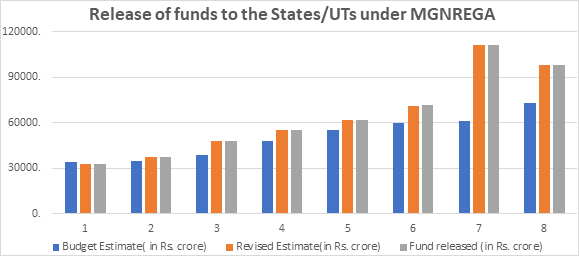

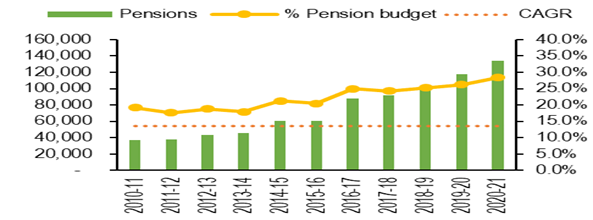

The global economy has been experiencing severe economic downturns since 2008. Much before the sub-prime crisis triggered the collapse of global trade, the world economy started experiencing recessionary trends. The European debt crises, the US-China war, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Russian-Ukraine war, among others, have significantly influenced the world economic outlook in the last decade. Amid such a crises prone period, even though the growth of trade has also been sluggish, the world trading platform has experienced a structural transformation creating several new opportunities for emerging and developing market economies. More than ever, international trade and commerce are now considered as critical weapons to ensure world peace and harmony, as these escalate the cost of future conflicts. This ideology though is not new. Mill (1848) also emphasised how international trade renders inter-country wars obsolete by enhancing their interdependences. However, today, the definition of trade has changed drastically. Unlike the traditional concept where production processes used to happen domestically and countries were engaged in the export and import of only final goods and services, in today’s world, there is no product which is made in a single country. The new trade reality is now demonstrated by the so-called Global Value Chains [or, GVCs], which are guided by fragmented production structures spread across different countries in the world. For example, as explained in a recent study by Xing and Huang (2021), a smartphone finally assembled in China contains components from several countries, such as visual design and power management module from the USA, computer codes from France, printed circuit board from Taiwan, silicon chips from Singapore, memory chips from Korea, and precious metals from Bolivia.[1] Another example is that of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner (originally an American product), the fragmented value chain of which, is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: GVC of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner Aircraft

Source: Adapted from <https://modernairliners.com/>

Thus, Figure 1 clearly demonstrates how in the new world of highly complex international production chains, goods cross several borders multiple times before reaching their end customers. To put it another way, this suggests that what we see happening in the world today isn’t really trade in final goods or services, but rather trade in intermediate inputs, materials, components, activities, or tasks. Rapid technological development, a steady decline in tariffs, lower costs for shipping and logistics, organisational innovations, etc. are just a few of the factors that remarkably decreased the cost of coordination between nations and enabled this process of global production sharing. The upper panel of Figure 2, based on OECD’S TIVA database, shows how, in the past few decades, this type of trade has dominated global exports and imports, and today, contributes to more than 60 per cent of the world trade.

Figure 2: Gross Trade in (Final and Intermediate) Goods and Services, 1998 – 2018

Source: OECD TIVA (2021 Ed.); Authors’ Calculations.

In addition, it is crucial to understand that the network of trade is expanding not between countries or industries but rather between businesses/firms, the majority of which are overseas affiliates or subsidiaries of various multinational corporations (i.e., the carriers of Foreign Direct Investment).[2] This is what is referred to as intra-firm trade in the literature, which is distinct from international trade carried out between unrelated parties. In a recent interaction with Financial Express, Pant and Bimal (2020) noted that

“Estimates suggest that about a third of global trade occurs in the form of intra-firm trade among MNEs;[3] the remaining two-thirds occur either as exports by MNEs to non-affiliates or trade among non-MNE national firms.”

In fact, the value of these intra-firm trade flows has increased as a result of MNCs’ expanding operations and rapidly emerging GVCs in the past decade or so. Based on the OECD’s database on Activities of Multinational Enterprises [AMNE], it has been estimated that these companies contribute to approximately 36 per cent of the global output, which accounts for about two-thirds of the world exports and more than 50 per cent of world imports. The UNCTAD [United Nations Conference on Trade and Development] estimates also suggest that around 80 per cent of global trade takes place under the purview of MNCs. However, this type of trade occurs only when MNs make investments abroad, referred to as Foreign Direct Investment [or, FDI]. Thus, in today’s GVC-driven era, FDI is serving as a conduit for the growth of trade flows. The main argument is that, in the present-day world, it is impossible to examine trade policy in isolation or to disentangle it from FDI policies.

To discuss the linkages between international trade and FDI, let us first understand the definition of Foreign Direct Investment, and how it differs from Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI) or what we call Foreign Institutional Investors (FII) in India.

Until about the early 1960s, FDI, like other forms of international investment used to be considered as a part of international capital theory. It was actually seen as a response to interest rate differentials between countries around the globe. Thus, it was recognised that, similar to trade in goods, a capital-scarce country (the one which offers higher return) imports capital and this continues up to the point where the return to capital gets equalised internationally. This explanation is analogous to the predictions of the standard Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) theory of trade.[4] Hence, it was thought that trade in goods could substitute for the international movement of factors of production, including FDI. But, with the failure of this capital theory in explaining most of the rise in international production (in contrast to just capital movement) during the late 1950s, efforts were made to analyse them from the trade theorist’s point of view. Only then, it was realised that trade and FDI are actually two different sides of the same coin (Pant and Srivastava 2015) and hence, they cannot be studied or analysed in isolation.

It was John Dunning who, in his 1980 seminal work, defined foreign direct investment based on what is popularly referred to as the ‘OLI’ paradigm, where O stands for Ownership, L for Location, and I stands for Internalisation. According to him, these three are potential sources of advantage that underlie a firm’s decision to become a multinational corporation. The first component ‘O’ addresses the question that why some firms go abroad, and suggests that a successful MNC has some firm-specific advantages, which allow it to overcome the costs of operating in a foreign country. Location advantages, on the other hand, deal with the question of where an MNC chooses to locate and suggest why it sometimes becomes profitable for a firm to locate itself in different countries, rather than producing and exporting from its parent country. Lastly, internalisation advantages influence how a firm chooses to operate in a foreign country, trading off the savings in transactions, hold-up and monitoring costs of a wholly-owned subsidiary, against the advantages of other entry modes such as exports, licensing, or joint venture. This implies that Foreign Direct Investment, as distinct from FPI or FII, does not just include the transfer of foreign capital from an enterprise in the source to another related entity in the host country, but also the transfer of know-how in the form of advanced technology, managerial expertise, or any other firm-specific factor.[5] Put differently, FDI combines three elements, viz. trade in commodities, services (for example, managerial services) and international technology flows. Secondly, most direct tax treaties between nations provide favourable treatment in the withholding tax rates applied on dividends/royalty payments among related enterprises, acknowledging the relationship between FDI flows and the production capacities of firms (Pant 2014).

In fact, as explained in Pant and Srivastava (2015), an investor in the parent country decides to switch to domestic production in the other country (i.e., it opts for FDI), when either entry barriers like tariffs make its exports uncompetitive, the other location gives it access to critical inputs at comparatively lower costs (vis-à-vis, the parent country), or when such a move becomes necessary to internalise the firm-specific advantages. With the establishment of the World Trade Organisation [WTO], the world has already experienced a gradual decline in tariff rates imposed by different countries. Hence, as argued in Huria and Pant (op. cit.), it is the latter reason that presently explains the expansion in the flows of FDI. This is because even if trade is free but FDI flows are restricted, it will be difficult for an economy to deepen its integration with the world market via GVCs. For one, restrictions on FDI inhibit the flow of technology and hence, the country’s technology-based trade. Secondly, no or lower levels of integration with global value chains (due to restrictions on intra-firm trade) may limit trade in intermediate inputs, which, in turn, could render a nation less competitive in the manufacture of a good (or goods) in which it had previously enjoyed a comparative advantage. Nevertheless, it is equally important to recognise that this association between FDI and trade could be complex and vary across countries, industries, production stages, and types of investment, etc. For example, while liberalised trade and FDI policies may foster a favourable correlation between the two, higher regulatory interventions in an industry in the form of tariff or non-tariff barriers, tax-based subsidies, etc. could potentially offer substantial incentives to the MNC to replace trade with FDI.

Tables 1 and 2 encapsulate Pearson’s pairwise correlation coefficients (measuring the strength and direction of the linear relationship) between different FDI and trade indicators (at the aggregate and sectoral level) for the world economy.

Table 1: Pearson’s Pairwise Correlation Coefficients – Trade and FDI, World (1970-2021)

| Percentage Shares in GDP |

Total Exports |

Total Imports |

Total Trade |

| Net FDI Inflows |

0.714* |

0.731* |

0.821* |

| Net FDI Outflows |

0.654* |

0.676* |

0.780* |

| Total FDI Flows |

0.701* |

0.719* |

0.817* |

Source: World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) Database; Authors’ calculations. Note: * represents significance at 1 per cent level, Total trade represents the total of goods and services trade, Green highlights represent the top three correlations. Interestingly, all the correlations are above 50 per cent, and the majority of the correlations are above 70 per cent (i.e., closer to perfect correlation).

Table 2: Pearson’s Pairwise Correlation Coefficients – Goods, Services Trade and FDI, World (1970-2021)

| Percentage Shares in GDP |

Goods Exports |

Goods Imports |

Goods Trade |

Services Exports |

Services Imports |

Services Trade |

| Net FDI Inflows |

0.717* |

0.745* |

0.721* |

0.729* |

0.662* |

0.704* |

| Net FDI Outflows |

0.665* |

0.699* |

0.669* |

0.660* |

0.581* |

0.635* |

| Total FDI Flows |

0.707* |

0.736* |

0.711* |

0.711* |

0.638* |

0.686* |

Source: WDI; Authors’ calculations. Note: * represents significance at 1 per cent level, Green highlights represent the top three correlations.

At the aggregate level for the world economy, Table 1 shows that trade and FDI are significantly and positively correlated with each other – be it the association between inward FDI and exports/imports, or the outward FDI or total FDI with exports/imports. Further, Table 2 replicates the analysis by incorporating information separately, on goods and services trade. Once again, we find that there exists a direct positive association between the two, indicating their complementarity. Though our analysis is indicative, it clearly makes a strong case for examining trade and FDI policies in a comprehensive and coherent framework.[6]

But, is this link well established in India’s trade and FDI-related policies? – Below we discuss some of the evidence in this regard, and suggest a possible way forward.

The Case of India

The lower panel of Figure 2 and Tables A.1, A.2 in the appendix to this article, show that India’s trade composition and the trade-FDI link are in line with our observations for the global economy. In fact, the correlation coefficients, on average, are higher in the case of India, than in the world, indicating the strength of the positive association between international trade and foreign direct investment. The last decade has witnessed several initiatives on the part of the country’s government to improve the ease of doing business, and make the country one of the most attractive FDI destinations in the world. In 2011, the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (erstwhile Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion [DIPP]) introduced the National Manufacturing Policy [NMP] to increase the share of the manufacturing sector in India’s GDP. National Investment and Manufacturing Zones have been established as an instrument to implement NMP, with an overall objective to facilitate the access to a requisite ecosystem for promoting world-class manufacturing activity (Press Information Bureau [PIB] 2018).

In September 2014, the government launched the Make In India [MII] programme with an endeavour to create and encourage domestic and multinational firms to develop, design, manufacture, and assemble products in India (PIB 2022b). As an initiative to simplify the process of approvals of inward FDI flows under government approval, the Union Cabinet abolished the Foreign Investment Promotion Board [FIPB] in May 2017. Henceforth, all the FDI proposals are required to be submitted through the DPIIT-managed Foreign Investment Facilitation [FIF] Portal, and respective applications are then screened by the concerned administrative ministries/department (PIB 2022a). Further, the government has also opened up several sectors for which FDI up to 100 per cent is permitted through the automatic route. A few examples are – ports and shipping, railway infrastructure, renewable energy, agriculture and animal husbandry, automobiles and auto components, single-brand product retail trading, and insurance intermediaries, among others.

While several other policy initiatives have also been undertaken to position India as the most attractive location for investment and conducting businesses (such as the Production Linked Incentive Schemes, PM Gati Shakti, India Industrial Landbank, the National Logistics Policy, Remission of Duties and Taxes on Exported Products, and the National Single Window System), however, at the same time, the country’s trade policy has been found to be highly restrictive in nature in the past one decade. Figure 3, based on the Global Trade Alert Database, shows the share of harmful trade interventions defined as those that restrict trade practices, as a percentage of total trade interventions for India for the period 2009-2022.

Figure 3: Harmful Interventions (% of total trade interventions), India (2009-2022)

Source: Global Trade Alert Database; Authors’ Calculations.

Except for the year 2011, as shown in Figure 3, the number of harmful trade interventions has always exceeded the number of liberalised trade interventions by the country. In fact, very recently, India was also flagged as highly restrictive in its trade practices by the industry associations of the United States of America, who pointed out that “although Prime Minister Narendra Modi has taken steps aimed at improving India’s business environment, India’s high tariff rates and restrictive border measures continue to limit manufacturers’ ability to invest in and export to India.”[7] This is a concern in itself as trade and FDI go hand in hand, and the rapidly expanding international production networks have only strengthened their association in the recent past.

The recent Budget announcements, however, seem to take a positive step in this direction. While the country’s long-due Foreign Trade Policy is still in the making, in this year’s Union Budget 2023-24, the country’s finance minister has reduced custom duties on a selected set of intermediate inputs to enhance domestic value addition, promote export competitiveness, and correct duty inversion. This is in contrast to the Union Budget 2021-22, where duties on imports of inputs were raised to ensure higher value addition within the country (even though the majority of India’s imports are of the intermediate category (see Figure 2, Lower panel)). Examples include some components used in TV manufacturing, electric heat coils, capital equipment for electrically operated vehicles and lithium battery production, parts of mobile phones, denatured ethyl alcohol for manufacturing of industrial chemicals, lab-grown diamonds, etc. Certain tariffs have been raised though for competing imports that may impact the local industry, such as rubber, toys and parts of toys.[8] Other initiatives include skill training programmes, the development of data processing centres, etc.

Despite these initiatives, one issue that still remains pertains to the bureaucratic separation of trade and FDI in India. While the definitional aspects of FDI are looked after by the country’s Ministry of Finance, the policies and control of FDI is with DPIIT. On the contrary, India’s international trade and trade-related policy matters are governed by the relevant trade policy division in the commerce ministry. More so, no chapter in its Foreign Trade Policy (FTP 2015-2020) thus far deals with investment-related provisions/norms (except for the section on Special Economic Zones/Export Oriented Units). This demands immediate attention especially when today, trade is determined more by technology and FDI, than by access to cheaper and abundant factors of production, and the emerging dynamics make it imperative for India to become a part of international production networks. The latter, as discussed above, are guided by MNCs to a great extent. The recent restructuring in the department of commerce may take this into account and create a separate wing to deal with trade and FDI policies simultaneously. Similarly, the government should consider the trade-FDI interlinkages while drafting India’s new FTP.

Lastly, akin to India’s policy framework, even at the multilateral level, there is no such comprehensive agreement that guides the trade in goods-services-investment nexus. However, acknowledging the link between the three, it seems that countries around the world are trying to bridge this gap by signing more and more regional trade agreements – now that these agreements also contain a specific chapter on investment-related provisions.[9] On the contrary, in India, the majority of the trade agreements still focus only on trade liberalisation, and exclude substantive provisions for foreign direct investment. Our recent work shows that this will not create significant gains for India, especially when it is now willing to conclude such deals with countries which are amongst its top FDI source economies.

Author Brief Bio: Prof. Manoj Pant is former Director/VC of IIFT and Sugandha Huria is a faculty member, IIFT.

References

Batra, R. N. (1973). Studies in the pure theory of international trade. Springer.

Dunning, J. H. (1980). Toward an eclectic theory of international production: Some empirical tests. Journal of international business studies, 11(1), 9-31.

Gereffi, G., & Lee, J. (2012). Why the world suddenly cares about global supply chains. Journal of supply chain management, 48(3), 24-32.

GOI. (2021). Union Budget 2021-2022: Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman. New Delhi: Government of India. Retrieved from <https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/bspeech/bs202122.pdf>

GOI. (2023). Union Budget 2023-2024: Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman. New Delhi: Government of India. Retrieved from <https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/>

Huria, S., & Pant, M. (2018). Foreign direct investment, welfare and wage inequality in a small open economy: theory and empirics. Indian Economic Review, 53, 131-166.

Huria, S., & Pant, M. (2019). Trade, Investment, and the Multilateral Trading System. In 20 Years of G20 (pp. 93-111). Springer, Singapore.

Krugman, P., Obstfeld, M., & Melitz, M. (2017). International Economics: Theory and Policy. Pearson Education.

Mill, J. S. (1848). Principles of political economy with some of their applications to social philosophy. 1857. George Routledge and Sons, Manchester, 467-474.

Mishra, A.R. (2022, November 27). US industry associations red-flag India’s ‘restrictive’ trade barriers. Business Standard. Retrieved from <https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/us-industry-associations-raise-concern-over-india-s-trade-measures-122112700668_1.html>

Pant, M. (2014, June 16). FDI or trade: end the confusion. The Mint. Retrieved from <https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/d35M6kulhSuMF4H5Bamc3N/FDI-or-trade-end-the-confusion.html>

Pant, M., & Bimal, S. (2020, May 28). Combating economic downturn post Covid-19 pandemic: Sync trade and FDI policies. Financial Express. Retrieved from <https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/combating-economic-downturn-post-covid-19-pandemic-sync-trade-and-fdi-policies/1972883/>

Pant, M., & Srivastava, D. (2015). FDI in India: history, policy and the Asian perspective, New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan.

Press Information Bureau (2018, December 27). Establishment of NIMZs. Retrieved from <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1557424>

Press Information Bureau (2022a, May 24). Foreign Investment Facilitation Portal (FIF) completes 5 years since Union Cabinet decision to abolish FIPB. Retrieved from <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1827889>

Press Information Bureau (2022b, December 16). Make in India facilitates investment, fosters innovation, helps build best in class infrastructure. Retrieved from <https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1884260#:~:text=’Make%20in%20India’%20is%20an,manufacturing%2C%20design%2C%20and%20innovation.>

Xing, Y., & Huang, S. (2021). Value captured by China in the smartphone GVC–A tale of three smartphone handsets. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 58, 256-266.

[Data] Global Trade Alert Database: https://www.globaltradealert.org/

[Data] OECD Activities of Multinational Enterprises Database: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/amne.htm

[Data] OECD Trade In Value Added Database: https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/measuring-trade-in-value-added.htm

[Data] World Bank’s World Development Indicators Database: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

[Website] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development <https://www.oecd.org/>

Appendix

Table A.1: Pearson’s Pairwise Correlation Coefficients – Trade and FDI, India (1970-2021)

| Percentage Shares in GDP |

Total Exports |

Total Imports |

Total Trade |

| Net FDI Inflows |

0.898* |

0.883* |

0.892* |

| Net FDI Outflows |

0.721* |

0.733* |

0.745* |

| Total FDI Flows |

0.876* |

0.867* |

0.876* |

Source: WDI; Authors’ calculations. Note: * represents significance at 1 per cent level, Green shaded cells represent correlation above 0.8.

Table A.2: Pearson’s Pairwise Correlation Coefficients – Goods, Services Trade and FDI, India (1970-2021)

| Percentage Shares in GDP |

Goods Exports |

Goods Imports |

Goods Trade |

Services Exports |

Services Imports |

Services Trade |

| Net FDI Inflows |

0.863* |

0.867* |

0.871* |

0.916* |

0.800* |

0.903* |

| Net FDI Outflows |

0.686* |

0.705* |

0.703* |

0.741* |

0.711* |

0.755* |

| Total FDI Flows |

0.840* |

0.849* |

0.851* |

0.895* |

0.799* |

0.888* |

Source: WDI; Authors’ calculations. Note: * represents significance at 1 per cent level, Pink highlights represent the top three correlations while green and pink shaded cells together represent correlation above 0.8.

[1] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] has also demonstrated several such cases with the help of it Trade In Value Added [TIVA] Database.

[2] Gereffi and Lee (2012)

[3] Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) and Multinational Companies (MNCs) are used synonymously in the trade-FDI literature.

[4] In a 2-country, 2-sector, 2-factor world, Hecksher-Ohlin Theorem states that a country should export the good which utilises its abundant factor of production intensively, and import the commodity which is intensive in the use of its scarce factor of production. For example, if the world market comprises of only India and the United States of America, with India having comparatively higher access to labour relative to that of Capital, while the US is relatively richly endowed with capital, then as per the H-O theory, India should export the labour-intensive good (say, textiles) to the USA. On the contrary, the USA should export machinery (i.e., the capital-intensive good) to India (See any textbook on trade theory such as Krugman, Obstfeld, and Melitz (2017) or Batra (1973) for details).

[5] Huria and Pant (2018)

[6] The literature now consists of a plethora of empirical studies examining the link between trade and FDI at various levels of analyses. For a detailed review, refer to Pant and Srivastava (op. cit.).

[7] Mishra (2022)

[8] Government of India [GOI] Budget Speech (2021, 2023)

[9] Huria and Pant (op. cit.)