Fashionable topics are obscure. The information available on fashionable topics is often more by factors than the information supplied. Means, a lot of information is concocted on the go. Who does not want to be associated with something that is considered important? Cryptos are today in thousands with Bitcoins and XRPs leading the way. Through this article we will examine all different aspects of cryptos.

Technology

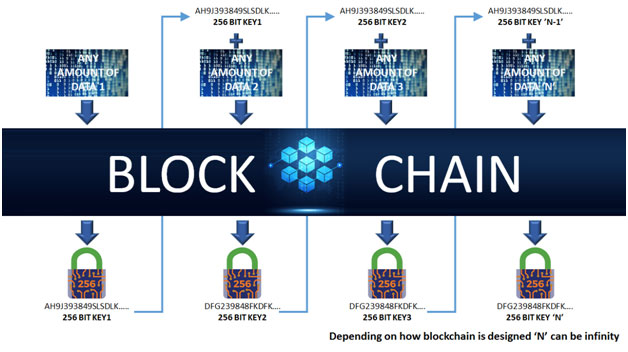

Usually cryptocurrencies are created using a technology called blockchain, though not all cryptocurrencies are blockchain-based. So, what is a blockchain? It is a mechanism of generating 256 bit crypto-keys (an alphanumeric code) from the collective data submitted, and then including this key generated in previous sessions as part of the data submitted in every next session. Entry is made in a commonly available ledger, which makes such entries immutable and hence safe. There is no limit on the volume of data, and each submission process includes the previous key.

The Blockchain carries none of the data, which may be left with anyone including the initial owner. Only the block keys are noted in the Blockchain. Each blockchain entry every few minutes or seconds is shared amongst and machine-accepted by all the participants of the main blockchain participants, called nodes.

In bitcoin, the data that forms the bitcoin is ‘mined’ (discovered by solving a mathematical computational problem), which keeps on getting more and more tedious, difficult, hence time & energy consuming, constantly enhancing the cost of the mining of bitcoin. Other cryptos have different mechanisms.

Is Blockchain and Cryptocurrency one and the same thing?

Not really. Blockchain is a technology that can be used for any purpose. Indeed, it is being used today for invoicing, legal documents, notary stamp papers, for smart contracts (discussed ahead), and even software creation. The applications are myriad. Within so-called cryptos, there is Bitcoin, which is a full-fledged cryptocurrency and beyond any legality or illegality as it has no promoter, no operator, no server and is collectively managed by the people who own it. ‘XRP’ of Ripple Labs, which is also cryptocurrency is completely legal and is used for international inter-bank payment settlements (prospective competitor to SWIFT) at less than 50% of the current costs. Hence, a large number of banks globally (300+) are subscribers to their service. XRP operates completely legally as a software-based settlement system amongst banks and at last count had a market cap of USD 11.35 billion.

Furthermore, there are more and more crypto-based products, which are not currencies. With varied alterations in the underlying blockchain technology, they are ending up in the market almost at the rate of few numbers a week. Therefore, it is important that in the context of this article, Blockchain refers to a technology, Crypto refers to any class of digital asset or instrument financial, legal or other, while Crypto-currency refers to a blockchain based money or money equivalent.

To unravel the conundrum that crypto and the information haze around it represent, let’s go back to first principles.

What is Money?

Believe it or not there are different schools of thought on what is money. There are classical schools and now there is Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and another labyrinth of ideas as to what is money. To avoid drowning my readers in this ontic ocean which has as much economic theory as history in it, I draw upon the current simple and superficial definition. “Money is an obligation undertaken by the Reserve Bank of India to exchange a submitted currency note for another one of the same number.” The INR100 note, if brought to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) will be exchanged for another INR100 note. That is all that RBI undertakes as an obligation. You don’t get gold or USD or sacks of wheat. Just another note for the one you submitted back. A currency note, therefore is an undated promissory note (debt obligation) of the exchequer.

What backs the fiat?

Nothing other than the revenues of Government, which most often are less than their expenditure in most nations.

So am I holding shares of a loss making enterprise?

Thematically, yes. But in practise it is slightly different, especially with a monopoly like a Government. They can afford to run losses and be credible.

Why can’t (don’t) Governments run proficits (Govt with revenues exceeding expenditure) rather than deficits?

This has nothing to do with economics. It is more about politics and social theory that a nation adopts. Proficits are run by only two types of nations: (a) Some relatively small and extremely rich European nations (not touched by the two world wars of the last century) with colonial resources left over from 300 years of plunder of Asia, Africa and South America and with high per capita income along with lowest standard deviation in per capita income can afford to be proficit states (they need little public welfare); (b) Those whose equity (treasury obligations of the sovereign) on the international debt markets takes a major hit and in a bid to shore up their reputation, they become like a big company for some time. Russia is one of few such examples after the sovereign debt default on 17 August 1998 by the Sergei Kirienko Government.

Sensible, good-health States are those that ensure zero proficit. This is sensible as any good state with its means to raise money anytime from the domestic and international markets or print its own, should ideally run like a not-for-profit venture. Welfare states are different. They believe that current inequality in availability of resources among their population and the resources that they require to run themselves (the Govt.) and build infrastructure and defence, should not be extracted back as taxes from the rich and affluent, but should be extracted as Treasury Bonds from the rich so that it keeps on lying on their balance sheets as an asset. Please know that every individual who has even INR 100 deposited in a bank, has Government assets on his personal or organisational balance sheet. It’s just that he does not know about it (it happens through Banks, who are bound to buy T-Bills and maintain SLRs). In venture investment business, there is a simple mechanism to evaluate anything, anytime. It is called, “see the exit value”. If the Govt. of a nation goes belly up (it happens all the time, in one or other country in the world, so it is not a Black Swan event), what is the value of the T-Bills? Actually, little.

Back to the modern welfare state, it replaces high taxes with the Govt. obligations, thereby giving a win-win, feel good effect. For purposes of altruism, I concede running some fiscal deficit is okay. Let the poor be assisted without harming the rich (that is the motto of fiscal deficits). But it should be within sensible limits. I desist from recommending those limits as that is not the subject matter of this article. But one ratio that no one ever publishes is the proportion of fiscal deficit caused by Govt.’s expenditure on sustaining itself. Here I have problems, because if this ratio is high, it is nothing but a Venture which has raised angel investment and is spending money not on the business that generates revenues, but on high salaries and fancy cars.

How are Govt bonds different from those issued by large corporations?

Just as the Govt. can never default on payments in national currency, they can tap on a computer a few times and generate as much money as required to honour the bonds. But the question remains: what will the money mean to the bond holders, if it is devalued? This brings us to a very critical juncture; what are the bond holders wanting? Is it Money (irrespective of what that money stands for) or Value? This question is relatively difficult to understand and answer. Because the bond holders are investing to avoid devaluation of their holdings. But in case the yield on a bond is fully compensated by inflation, the bond holder is actually reducing the worth of his money. Therefore, bonds of a very well managed corporation are safer than poorly managed Government. This brings us to the other painful incongruence that exists—Credit Ratings. Credit ratings of a legal entity cannot exceed the sovereign credit rating of the jurisdiction. This principle is followed by most rating agencies. This sounds theoretically sensible but has proven to be wrong in innumerable cases the world over. Currently, there are innumerable corporations in Spain and Italy, whose credit rating should be better than the corresponding Governments. This is a typical case of an insurance event, when emotion is let to govern the rational. Governments tend to provide a sense of security from the legislative and authoritative powers they possess.

What are limbic and cerebral markets?

Limbic economies are those where demand precedes and triggers supply. Cerebral economies, conversely, are supply-initiated demand triggered.

Modern Market Theory & the need for all powerful sovereign

The foundations of the theory that Governments are all powerful printers of currency, are flimsy. Indeed, the fact that firms can be more credible then the Governments in certain circumstances (I again quote Italy & Turkey as an example, where some Credit Rating Agencies decided to place companies ahead of countries) is itself a proof of this theory’s faultiness. In reality, in today’s globalised world, governments are economic agents like corporates. Yes, they are more powerful and in monetary economics, power = capability to manipulate or better said, power = capability of harmlessly-managed for oneself deviation by induction, from the spontaneous.

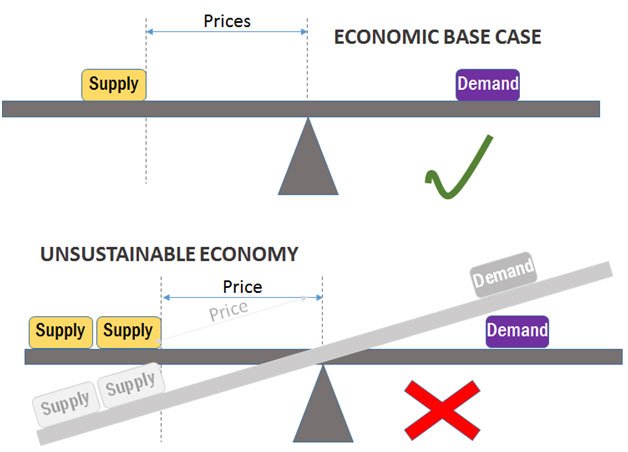

To finally come to the crypto and its logic, it is important to understand debt, which is of two kinds: Sustainable [maintains economic balance] and Unsustainable [promotes economic dis-balance].

In an informationally-transparent-market, ‘sustainable debt’ is the difference between demand and supply. Please note; it is the difference, irrespective of whether supply exceeds demand or vice-versa. The gap, whatsoever, among the two is sustainable debt without causing inflation or deflation (major change in prices). It is important to note that these gaps occur simultaneously in economies. In certain sectors, demand exceeds supply; in others, supply exceeds demand. ‘Sustainability’ manifests itself in the stability of the value of money.

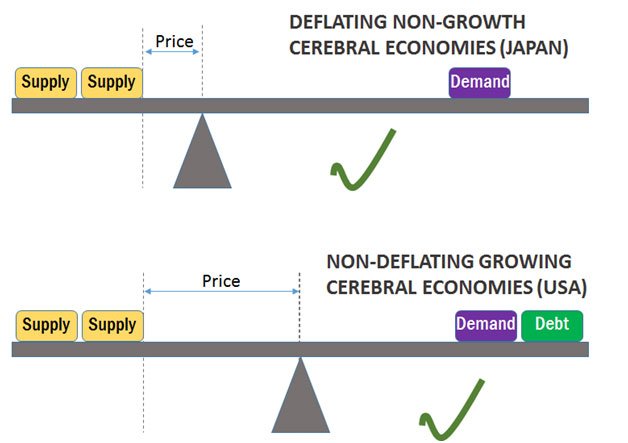

When supply is more, either the prices will fall (unsustainability) or people have to be provided debt to buy more + their consumption habits have to be ramped up substantially. Since the situation highlighted in the previous image is unsustainable, therefore one of the below mentioned two cases are chosen, depending on whether one is a deflating non-growth cerebral economy or a non-deflating growing cerebral economy.

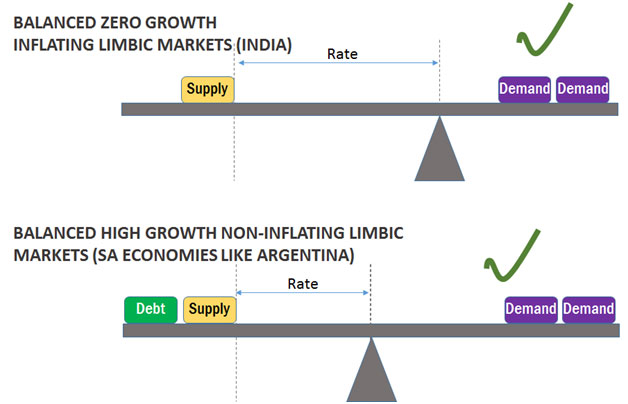

If demand is more than supply, one of the below mentioned are chosen. The 2nd on foresees providing debt to firms to ramp up production.

It is important to note that the complexity in an economy happens owing to simultaneous occurrence of all four mechanisms concomitantly, when specific sectors are a combination of cerebral/limbic, inflationary/deflationary/non-inflating in an economy. The complexity is a gaussian curve. Completely underdeveloped (usually limbic markets) and highly developed (usually cerebral markets) have clear choices. It is indeed the ones in the middle that face high-complexity choices and ideally very sector focused approach in policy making, which, if absent, will leave desired high growth a pipe-dream.

Conclusively, it is only social habits on one side and the innovative capabilities of the firms on the other that are constraints to growth. It is important to underline that demand (includes that which is domestic in origin as well as that generated by exports) and supply too is for both domestic market as well as imports.

Debt is growth, not money. When either supply or demand exceed the other, it leads to either people getting debt to buy more (with sustainable inflation in supply excess), or firms getting debt to produce more (in case of excess demand). “Money on the contrary is just another financial commodity and nothing more. It is subject to the same equilibrium economics as wheat or rice are.”

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), often referred to as Post-Keynesian Economics, assumes that Government’s money printing capability is the compensatory mechanism, keeping Government as a superseding mechanism over and above the economic agents—almost like a puppeteer. The fact however is that owing to legal and judicial parity that is available in India and most democracies between Govt. and non-Govt. entities in eyes of law; Govt. is just another economic agent, though with additional powers like emission of currency. The proponents of MMT especially in the United States are advocates of a superseding and unquestionable powers of the Govt. Worse, they believe in collective rationality and aptitude of Government. The latter is the most challenging and, in some cases, dangerous assumption, as systems like those of Government do not follow rationality, they create their own rationality and are hence, subject to the most irrational owing to cultural frames of operations to which they are subjected.

It is interesting that Bitcoin & Cryptocurrencies usually lie out of the purview of MMT. Proponents like Randall Wray, Mathew Forstater and Stephanie Kelton speak little on crypto or reject it as non-serious phenomena. I furthermore believe it is purposefully propped as it provides US Govt and extraordinary capability to manipulate & manoeuvre at the cost of others. MMT lends more economic credibility & authority to the US Govt than that, which is true.

Crypto and the New Economy

All the aforementioned were important to be understood by first principles for the understanding of Crypto’s role in making a new economy happen. Bitcoins are beyond the patience of most traditional economists. And they might be partly right in saying that once bitcoin is treated as a digital asset, its behaviour shall be no different from other similar asset forms. The major caveat that is unaddressed is the information plane. Information is the medium and milieu of all economic theories. If the information milieu changes dramatically, one might have a completely new set of substantially altered economic equations.

Bitcoin is excellent electronic money that finishes the rigging capability of individual states. It does exactly the same job as money, but the other way round: the total issued bitcoins are limited to 21 million. Therefore, if the entire world shifts to bitcoins, one will need no more economists as the growth of the world economy will be the growth in the rate of bitcoins—as simple as that!

For ease of use, Bitcoin can be endlessly reduced in denomination. It already has satoshi (The smallest bitcoin currency); then it will be milli-satoshi, micro-satoshi and so on, as technology allows for constant reduction of this denomination as per need and rise of the value of bitcoins. It will be an ideal capitalist, competitive economic model. Furthermore, while it will give a major startup advantage to the US, Europe and Japan; it will be a level playing field for the future. Because he who produces more of the needed and desired will win, irrespective of its location. In future, it will tilt in favour of those nations, which are less costly for production. It will therefore be a self-balancing mechanism, based on unemotional merit-based capitalism. This is quite in contrast to the superseding sovereign that MMT proposes.

What is so exciting about Cryptos?

The development quotient of a nation can indeed be estimated from the higher proportion of electronic payments vis-à-vis paperback. Electronic money clearly identifies the payee and the payer, making it relatively difficult to evade taxes, making money cleaner. Most transactions in North America, Europe and developed East Asia are electronic. Nevertheless, crypto-currency is very different from all existing electronic money transactions. It is important to observe that crypto currency is not one uniform lot in terms of technology. There are innumerable different technologies that are used for creating crypto currencies. Therefore, we focus on the minimum common denominator which is invariably available in every type of crypto currency. Following are the crucial features of crypto currency qua electronic money:

- Electronic transaction ledger rests with everyone. There is nothing to steal. And at the current level of computing technology, the ledger is immutable.

- Block chain does not require any central agency, authentication or trust centre (like banks) that authorises or underwrites a transaction and charges a commission on the same. Since a common ledger of entries is available, changes, if any made, are available for everyone. A simple analogue would be sharing a Google spreadsheet, such that each participant can make changes in the spreadsheet, but the changes are validated only when each participant agrees to the proposed change.

- Crypto-currency can be issued in lots, such that different lots are governed by different rules. Therefore, it is possible to create multiple currency types pretty quickly.

- If required, the issuer can exert control over the currency even after it is issued.

- Crypto currency can be created to be completely opaque or completely transparent along with automated reporting of various types of transactions including those which could tantamount to corruption.

- Critically, crypto-currency when programmed as a smart contract has the capability to work on its own without any action required to be triggered by the owner. It technically could become the Letter of Credit of the 21st century.

- Open electronic marketplaces make it extremely easy for the end user to transfer or exchange this currency globally, as all it needs is an internet connection to be accessed or used.

- Offline transfer of cryptos is possible. Indeed, it is even possible to print cryptos as tangible cards or tokens for easy offline interactions, which are accounted for once the transaction jumps over from offline back to online.

- Very importantly cryptos can(not) be made traceable. Traceability could bring in a new dawn of new economics, as lots of theories that economists have devised are actually for predicting behaviours to ultimately understand the flow of money in an economy. Crypto can provide economists and data analysts instantaneous understanding of currency vis-a-vis hundreds of markers, including the capability to see which sector has how much monetary gravity and what is the sector-wise rate of monetary circulation. This could, therefore, open the tummy of economics for relationship dynamics and knowledge. Relationship dynamics means the capability to see how, which relationships and dependencies are changing and by how much.

Aforementioned are pretty much the most gravitational changes that block chain brings to money vis-à-vis existing electronic money.

Need of a smartphone for carrying crypto-currency is a misnomer amongst the masses. It is only partly true. All crypto money is computed, binary money. A computing device is required only for transactions, especially those where one is a sender (not a recipient) of crypto-currency, quite like existing electronic money. Secondly, there is a possibility of creating very cheap electronic-wallet devices or cards that connect electronically and independently or parasitically (when in proximity or connected to a terminal, without its own display, like cards). These wallets can be produced so cheap that they can be provided free of cost by Governments to all its citizens. Pretty much like the Banks give away debit cards along with account opening.

Launch of DigiYuan and its repercussions on the World

#COVID-19 has eclipsed another momentous event—China launched its crypto-currency in May 2020. An official crypto-fiat built around block-chain is very different from cash or electronic money that exists today in mobile wallets and bank accounts. Through this article, we first understand the disparity between existing electronic money and block chain based crypto-currency, followed by the impact that Chinese DigiYuan could potentially have on China and the world.

In context of all the aforementioned, China’s launch of its crypto-Yuan is very significant. China achieved the status of an upper middle-income nation through prudent use of its inexpensive work force, making itself into the factory of the world and through financial policies that let it grow at an astronomical pace. It now clearly sees that depending on export for the next push in growth is not possible. Concurrently, One-Belt-One-Road has had an undulating beginning. China therefore, knows it needs to now grow its domestic market. Secondly, it needs a performance spurt. Weeding out corruption is a major efficiency exercise. It can easily add 1-2% points to growth annually. Besides which, it will have a cascading impact on a number of other aspects of economic, social, cultural and political life. It could also create a renewed interest in China as a great clean large market to invest and do business.

China is a single party authoritarian regime. Such a regime has complete control over national resources and can legally draw resources for its sustenance. The Party is the Government and hence everything belonging to the Government belongs to the Party. Therefore, institutional corruption, which in democracies exists through business-political quid-pro-quo for politicians to access resources for electioneering is not required. Corruption in such ‘institutionalised authoritarian’ nations is a result of an individual human’s propensity to monetise power for richer living or for accumulating further additional power. The word ‘institutionalised authoritarianism’ stands for one in which the public and the ruler are in an equilibrium that is discovered through decades long struggle amongst them, such that the endurance and reliability of such regime is as high as that of democracies, while those aspects of living, which free societies term as ‘absence of freedom’, are so deeply impregnated into the cultural fabric of the nation that they no more seems authoritarian. “Socio-political freedom has no absolutist existence or features, it is a bargain within the cultural context of a nation.”

By slowly replacing paper money with a crypto currency, China will be able to gradually weed out close to all individual corruption, technologically. This could lead to a much better performance, better economic efficiency and better image of China. Furthermore, a stable China with easily available Digi-Yuan for international transactions, could in no time become an international transaction currency, though it might never become a reserve currency for the same political reasons of opaqueness and authoritarianism. This will grossly impact the current status of US Dollar as the world money (currency of exchange and transaction) as well as the reserve currency. While the US Dollar will still retain the status of reserve currency; but the world money status might quickly decouple itself from the US and agglutinate to China. As mentioned above, a clean and transparent China will also attract attention and a second wave of investment. Where does it leave us in India, Russia, Europe, the US & others?

Remember the 70s? The US and China built a seller-buyer relationship that thrived for almost four decades. China will now build one with the developing nations of Asia, Africa, South Europe and South America. These nations will become the projections of Chinese power and rich in DigiYuans. Quite like China became rich in US Dollars and only now understands that it was fooled for exchanging its natural resources for a song and four trillion American promises. In this, India has been much more intelligent than Chinese; we exploited resources for ourselves, China ravaged them for the US!

Russia faces a lot of internal challenges, most crucially lack of ideology. Socio-culturally, Russians are very different from both Asians and Westerners. They operate most efficiently when provided a common clearly identifiable by most ideals. Happiness and prosperity for all has not really cut ice with Russia, notwithstanding repeated propositions of President Putin, who has dominated the Russian mind space for the last two decades. China has two very large neighbours—India in the South and Russia in the North. It is clear that China has learnt to deal with both adeptly. Russia is treated with equity and respect, something Europe and America failed to provide Russia. Russia with its large pool of resources and a sensible size economy will be major target markets for DigiYuan as the world money (transaction currency). Reasons are simple and straight: Euro, does not want to be one, Ruble cannot be one, so what is left is the US dollar that Russia dislikes and Digi-Yuan, which it will perhaps adopt and accept.

Africa, some parts of Asia (Iran, Pakistan etc.), S. America and all those being supported by China will have little issues with use of DigiYuan. Europe is orphaned, with identity lost to America, a lukewarm European United Front and contradictions within. They surely do not stand to compete with China. And individually, not collectively, (as EU) will subscribe to DigiYuan as a transaction currency. Having said the aforementioned, Europe will have a positive, but cautious approach rather than a camaraderie with China.

The US might subsequently be left with only India and the Middle East (till the monarchies don’t die along with oil, which though not immediate, but is now apparently declining on the horizon). Australia, Canada and the UK are too small and inconsequential separately, while their colonial past will never let them unite together. India is seen to be of no bother currently, as the democratic contradictions within India are seen as a safety valve that will never make India a threat for China. Assisted by the US, brooded by Europe and politically no more a push-over, could India gain from the current COVID crisis by being the other large market for sourcing, manufacturing, selling and exporting?

A popular Digi-Yuan will force other nations including India and the US to issue their own crypto-currency. With all crypto-currencies freely available on the internet, transferred without intermediary and state control, coupled with a very high level of universal awareness and connectedness amongst people of the world, the globe is poised to be more dynamic than ever. So brace for the change.

With Digi-money issued as a smart contract, the role of banks as medium of trust will be annulled completely. Would all money be crypto money, the role of banks will be reduced to asset management companies. Furthermore, with ever expanding role of relatively better algorithmic scrutiny and rating along with an easily analysable record of crypto-money, the role of Asset Management by Banks might also completely shift to data analytics and an AI system, which rates and assesses debtors, and provides the depositors to choose risk-return for themselves; in other words, a new era of crypto-bonds is visible on the horizon. This will be an end to banking as we know it now. Each of the aforementioned elements are individually already evolving.

Another major impact of gradual introduction and dominance of crypto-currency in China will be birth of new economics. Most Economics Nobel Laureates (including Abhijit Bannerjee) would have spent their life gathering monetary and other data from the economic limbs of a society—individual citizens—to see the impact of money, its distribution, its circulation speed etc, to verify the causes of trickle-down effect, if one exists. With complete traceability in crypto (one can, in one click, trace all the owners of each and every single Digi-Yuan from the day it was issued/mined to the present day), along with identification of the holder, most of these economic theories will be facts, rather than hypothesis in flux. What trickles down, what does not will be transparently visible and will cease being a matter of expert guesses and debates. This will enable a completely new type of development economics to be born in China. Akin to shooting a guided-missile, bang on target, then hurling tens of unguided projectiles, this development economics will be highly directed for the target population (directly or indirectly). Pilferage shall be marginal. Upliftment of underprivileged will be dramatically catalysed. And China will be driven into a new unmatched league of its own. And all this seems happening with their decisiveness. So brace for it.

So, will India rise to the occasion? The tone of the answer, like in any other democracy, will be decided by the people of India, the tenor by its leaders. India has always been more American than America. The best team work most Indians are capable of is when playing alone. Therefore, in some sense we are opposites of Russians. Russians have immense capability to unify around an idea but are lacking great unifying ideas. India has great unifying ideas but lacks any desire in its people to be in unison. “Constructive Union is a tendency of people to make an idea happen, Diversionary Union on the other hand is the one that happens when people unite to avert a calamity brought on them by nature or internal or external forces. Such unions are nothing but acts of collective survival. They are instinctive, not strategic.” There will be other outcomes of Crypto introduction, which includes automation of economics and a major replacement of economists by data analysts.

Deepak Loomba is Chairman of De Core Nanosemiconductors Limited, Gandhinagar, Gujarat.