“India is the only big economy which has delivered in letter and spirit on the Paris Commitment”[i] stated Prime Minister Modi in his address at Glasgow COP 26 Summit on 2nd November. He noted that India with 17% of the world’s population was responsible for only 5% of greenhouse gas emissions annually. He committed India to achieve the target of net-zero emissions by 2070 and reducing CO2 emissions by 1 billion tons by 2030. In one fell swoop, he silenced the critics (except of course the professional India baiters) and assumed leadership in the battle against climate change.

If the road ahead is bound to get more difficult, the journey thus far for India (and the developing nations) has not been easy either. “India has been a late starter and much of its infrastructure remains to be built. China’s emissions rise is likely to flatten as its years of intensive growth will soon be behind it, when it reaches its peak by 2030”.[ii] As such India’s GHG emissions are bound to rise, attracting mounting pressure, economic and political, from the sinners’ turned saints.

Climate change poses an existential crisis to mankind and is well described as Covid-like epidemic ‘in slow motion’. That comprehension has finally dawned on the decision-makers and the populace at large, the world over. What is still missing is a genuine sense of urgency and willingness to collectively put the shoulder to the wheel. Politicking, buck-passing and grandstanding, remain the order of the day, while the steady build-up of CO2 and other Greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere is choking the lungs of mother nature with ruinous consequences.

This short paper aims to look at the magnitude of the crisis, reasons for foot-dragging by the rich countries, and practical measures by the comity of nations to contain/reverse the damage. Humanity has no choice but to rise to the occasion. The only imponderable is whether or not substantive climate action will be initiated before nature’s balance is disrupted irreversibly.

Background

In the last 200 years, global temperature has risen by at least 1%. This is the result of the huge stock of greenhouse gases that have accumulated in the process of carbon-intensive development of the industrialised world with little regard for the environment. It is as if a thick blanket has enveloped the earth. Here it is important to distinguish between GHG stock and flow. The latter is the addition of GHG annually which currently measures a whopping 51 billion tons, while ‘stock’ represents the cumulative quantity of pollutants released by mankind. The restrictions imposed around the world during the Covid pandemic saw an overall decline in CO2 emissions of 5.6% in 2020.[iii]

GHG remains in the atmosphere for over 100 years and therein lies the foremost challenge. Even if the emissions are brought down to zero, it would take a century for the environmental poison to dissipate. Methane (CH4) is 262% and nitrous oxide (N2O) is 123% of the levels in 1750 when human activities started disrupting Earth’s natural equilibrium. “The amount of CO2 in the atmosphere breached the milestone of 400 parts per million in 2015. And just five years later, it exceeded 413 ppm”.[iv] Roughly half of the CO2 emitted by human activities today remains in the atmosphere. The other half is absorbed by oceans and land ecosystems, which act as “sinks.”

The challenge will get compounded with the addition of some 3 billion inhabitants in Africa between 2020-2100. The African population is expected to increase from 1.3 billion to 4.3 billion despite significant resource constraints, socio-political instability and security deficit. This would greatly aggravate inter and intrastate strife. Most of the increase will come in sub-Saharan Africa, which is expected to more than triple in population by 2100.[v] Meanwhile, the European population would shrink. The Asian population is likely to increase from 4.6 billion in 2020 to 5.3 billion in 2055, when it would start shrinking. China’s population should peak in 2031, while India’s should grow until 2059 to touch 1.7 billion.

In spite of damaging the environment, polluting the rivers, cutting down trees, and generating unconscionable levels of plastic waste, experts were divided about the extent of the actual impact on the climate. Many believed and some still do, that climate change is a boogie meant to extract resources from the industrialised world and pave the way for the development of new forms of energy and technologies, to the detriment of oil-producing nations. Nevertheless, the first serious attempt at taking stock of the situation was made at the Rio conference in 1992 which recognised the need for taking corrective measures and put the onus essentially on the industrialised world under the principle of ‘polluter pays’. Both mitigation and adaptation measures were envisaged. It was agreed that the rich nations will help the developing countries in curtailing pollution and enhancing energy efficiency.

The 1997 Kyoto Summit which was meant to concretise the gains of Rio turned out to be a tame affair. President Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol but was unable to secure Senate backing. A bigger fiasco was to follow in 2017 when President Donald Trump, a climate sceptic, decided to pull out of the Paris Accord (2015). The withdrawal came into effect three years later thanks to an inbuilt stipulation that no nation will be able to quit before 3 years of signing it. Mercifully, with the change of regime, President Biden re-joined the Accord. All the same such a yo-yo approach does not augur well for effective climate action, particularly since the US is the lead actor in the matter. Given the inevitable electoral cycle in the US, the COP (Conference of the Parties) would have to brace for such disruptions, unless there is a groundswell of support for effective climate action in the US and politicians fear a voter blowback for being seen as a naysayer.

Climate solutions entail a cost, are not attractive politically and gains are intangible. In other words, climate action does not win votes, as it is an investment into the well-being of future generations while politics is mostly about instant gratification. There are a handful of leaders who have the vision to recognise that the present generation has a fiduciary responsibility to leave the earth habitable. Meanwhile, the industrialised world has been looking at ways to wriggle out of the commitments. They ganged up to gradually chip away at their responsibilities to facilitate mitigation and adaptation by the rest of the world. The first to be attacked was the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) which front-loaded action by the developed Nations.

In 2000, the biggest polluters were the US and European Union, both in terms of absolute and per capita emissions. India’s per capita emissions, for example, was barely 5% of that of Europe. By 2020, the per capita gap started to shrink, emissions by the developed nations have peaked or are close to peaking while that of the developing countries are naturally rising. It may be pertinent to note here that though at the receiving end, the developing countries have not been very successful in staking out common positions nor do they have institutionalised consultative mechanisms like the G7. Just to cite one example, Brazil, South Africa, India and China constituted a group called ‘BASIC’ in November 2009, to co-ordinate positions on negotiations on climate change. They worked well during COP 17 in Copenhagen and COP 18 in Doha in 2012. However, China broke ranks when it outgrew BASIC. “As the run-up to the 2015 Paris climate conference showed, China’s interests in climate change negotiations could now be reconciled with those of the US. It was the China-US joint announcement and statement that largely produced the Paris outcomes” writes Shivshankar Menon.[vi]

The 2015 Paris Conference introduced the concept of voluntary commitments “in the form of ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDC) targets, to be communicated by each signatory to the UNFCCC. It represented “a ‘bottom-up’ approach where countries themselves decide by how much they will reduce their emissions” by a certain year. It essentially forces developing countries to share the burden and responsibility of climate action and dilutes the principle of CBDR reached in Rio. The Paris Agreement was signed by almost all (193) countries in the world at COP21 in Paris in 2015. Its other salient outcome was an agreement to limit the rise in the global average temperature to ‘well below’ 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels, and ideally to 1.5 degrees;[vii] strengthen the ability of nations to adapt to climate change and build resilience; and align all finance flows with ‘a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’. The affluent nations committed to providing $100 billion annually by 2020 which constitutes the core for climate action.

Glasgow Summit of COP26

The NDCs submitted under the Paris Agreement were collectively not ambitious enough to limit global warming to ‘well below’ 2 degrees, forget 1.5 degrees. However, there is a provision for the signatories to submit more ambitious – NDCs every five years, known as the ‘ratchet mechanism’. COP26 was the first test of this ambition-raising function. And that objective was well served. 126 countries submitted new NDC targets while 41 countries did not, as of 12 November 2021. The new NDC targets cover 90.8% of global emissions.[viii]

The UK has, for instance, pledged to reduce emissions by 68 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and 78 per cent by 2035. The European Union (EU) is aiming at a reduction of at least 55 per cent by 2030 relative to 1990 levels, and the US is targeting ‘a reduction of 50-52 per cent’ compared to 2005 levels. Considerable skepticism existed among the participants at Glasgow summit. Hardly anyone spoke of climate justice and the rich nations remained hesitant to walk the talk. It further sanctified the concept of net-zero emissions.

Magnitude of the Challenge

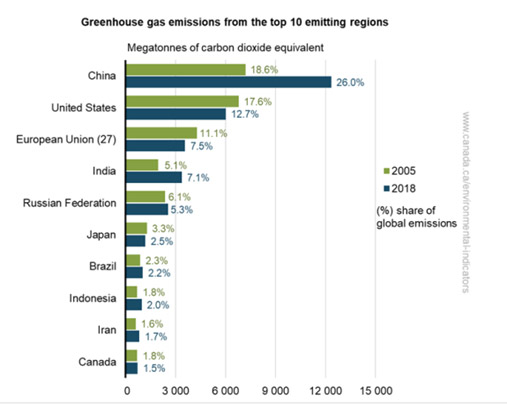

At the beginning of the industrial revolution, atmospheric CO2 levels were roughly 280 ppm, which rose by the early 21st century to 384 ppm and by 2020 to 413.2 ppm.[ix] The US has emitted 399 billion tonnes (bt) of CO2 or 25% of the global total since 1751. China, which was a late starter, has already released 200 bt of pollutants since 1899 or 13.8% of the global total, as compared to a mere 3.21% by India over the same period. But Chinese annual emissions are now the highest at 10.17 bt annually or 20% of the global total. They will continue to rise and peak by 2030. Emissions of Europe and the US have already peaked.

Graph: GHG emissions from the top 10 emitting regions[x]

Security, health and economic impact

The impact would be as under:[xi]

- By 2050, more than 143 million people could be driven from their homes by conflict over food and water insecurity and climate-driven natural disasters according to the World Bank.

- Rising temperatures threaten biodiversity, with one million species in danger of extinction that affect crop growth, fisheries, and livestock.

- Warmer temperatures could expose as many as one billion people to deadly infectious diseases such as Zika, dengue, and chikungunya.

- A warmer climate could lead to an additional 250,000 people dying of diseases including malaria each year between 2030 and 2050, as per the World Health Organisation.

- The Red Cross estimates that more than 50 million people around the world have been jointly affected by COVID-19 and climate change.

- An additional one million people could be pushed below the poverty line by 2030 due to climate change as per World Bank estimates

- By 2050 at least 300 million people who live in coastal areas will be threatened by dangerous flooding.

- A Stanford University study found that climate change has increased economic inequality between developed and developing nations by 25% since 1960.

COVID-19 pandemic is likely to exacerbate the impact of climate-driven challenges and disrupt efforts to address them. Climate-driven disasters threaten to overwhelm local health systems at a time when they are already under extreme stress, and the costs of damage and recovery from a natural disaster when compounded with the pandemic are estimated to be as much as 20% higher than normal.

Where does India stand?

India is the 7th most vulnerable country to climate change, according to Global Climate Risk Index 2021, both in the mainland and her over 7000 km long coastline. The good news is that India is “now ranked 10th in fighting climate change”[xii] —and is probably the only G20 country compliant with its commitments and the Paris agreement. India has already reduced the emissions intensity of GDP by 28% over 2005 against its target of 33-35 percent by 2030 and increased her installed capacity of renewable energy to 38.5% against its target of 40% by 2030. At Glasgow, India committed 500 GW of renewable energy by 2030 equivalent to almost 50% of her capacity.

The task is cut out for India especially as the “energy investment requirement will rise from about USD 70-80 billion annually to USD 160 billion. Much of India’s wealth is yet to be created. It is estimated that 60% percent of India’s capital stock—factories and buildings that will exist in 2040—is yet to be built”.[xiii] Therefore, the adoption of green technologies is the best option for growth, to create a more responsible and sustainable economy. “USD 10 billion of FDI in the past 20 has been received in the renewable energy sector but there has been a slowdown since. Also, in the last 2-3 years Indian investment in the renewable energy sector especially wind energy has fallen.”[xiv] India has taken a slew of salutary initiatives to mitigate the impact of and adapt to climate change including launching the National green hydrogen mission to promote production and usage of green hydrogen across sectors; a Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) of 25 countries to reduce risk through research innovations and share of good practices has been established; ISA or the International Solar Alliance was unveiled in 2015 along with France which now has 101 member-countries (the US joined in Glasgow) to promote solar energy. A Rs. 400 / ton cess on coal (or carbon tax) has been quietly imposed.

India has substantial low-grade coal reserves and her dependence on coal-fired thermal plants will continue for the foreseeable future. Coal-based plants are the most polluting. Chinese coal consumption comprises 50% of the global total and India’s 11%. “For years, climate geopolitics was premised on the approach that developed economies must bear the lion’s share of mitigating climate crisis. It was considered unfeasible to impose the same burden on developing economies. India has reshaped that understanding of climate commitments fundamentally—we have shifted the global balance of power by showing that developing countries can lead the way in pledging comprehensive climate targets while also successfully meeting their socioeconomic objectives”[xv] says Minister Puri, making a virtue of necessity.

But on the flip side, partly due to the Covid pandemic, mass poverty has risen in India from 60 to 134 million as per Pew Research Centre measured on the yardstick of people earning up to USD 2 in PPP terms.[xvi] India has also become the 3rd largest emitter of GHG globally, contributing 6.6% of the total as against 27% by China and 11% by the US. But in per capita terms, Chinese emissions are four-fold that of India.

Major steps being taken to combat climate change

Renewable and Nuclear Energy

Two-thirds of global energy is generated by fossil fuels, which account for 67% of annual GHG emissions. Oil-producing countries and multinational oil corporations have considerable clout and resources to lobby the decision-makers and blunt any campaign to kick the oil addiction. The better way is to innovate and come up with green energy solutions like renewable energy which today is the cheapest form of energy. The green premium, for the generation of renewable power, especially solar, has come down dramatically. As per IEA (International Energy Agency), “The world’s best solar power schemes now offer the ‘cheapest electricity in history’ with the technology cheaper than coal and gas in most major countries”.[xvii] But battery storage poses a huge challenge as a cost is as high as dollars 200 per unit. According to IEA report the technology for energy transition up to 2030 is proven and known. But only 50% of the technology needed for the transition during 2030-2040 has been developed so far.

The Fukushima incident adversely impacted national plans of enhancing nuclear energy capacity. IEA recommends that nuclear energy comprise 10% of the total capacity of a nation. The reason is that, other than renewable energy, nuclear power is the cleanest. It is impossible to switch to 100% renewable energy capacity as the generation is weather-dependent. Therefore, to avoid blackouts and ensure continuous supply some amount of nuclear capacity is necessary. Taking all factors into consideration, Bill Gates in his new book also recommends nuclear power as the best non-renewable energy source.

Presently, France is the biggest user of nuclear energy comprising 70% of its total capacity; it is about 20% in the case of the US and Europe and a mere 2% in India. 4% of Chinese capacity is nuclear but could rise to 10% by 2030 as some 150 nuclear plants are proposed to be established.[xviii] Research on producing three types of hydrogen power is being stepped up. The big difference is that the burning of hydrogen produces water instead of CO2.

Green Buildings

Globally, the buildings sector consumes more than half of all electricity for heating, cooling and lighting and accounts for 28 percent of energy-related greenhouse-gas emissions. Green buildings represent one of the biggest investment opportunities of the next decade—USD 24.7 trillion across emerging market cities by 2030.[xix] Most of this growth will occur in residential construction, particularly in middle-income countries. Most of this investment potential—$17.8 trillion—lies in East Asia Pacific and South Asia, where more than half of the world’s urban population will live in 2030. The investment opportunity in residential construction, estimated at $15.7 trillion, represents 60 percent of the market. There is a strong business case for growing the green buildings market. Construction of Green buildings could cost up to 12 percent more, which is easily offset by a reduction in operational costs up to 37 percent, higher sale premiums of up to 31 percent; up to 23 percent higher occupancy rates, and higher rental income of up to 8 percent.[xx]

Climate Finance

The transfer of “climate finance and low-cost climate technologies have become more important. India expects developed countries to provide climate finance of USD 1 trillion at the earliest. Today, it is necessary, that as we track the progress made in climate mitigation, we should also track climate finance. “The proper justice would be that the countries which do not live up to their promises made on climate finance, pressure should be put on them”, said PM Modi, who did not mince his words at the Glasgow summit.[xxi]

A Green Climate Fund was established in 2010 by some 190 countries to help developing countries respond to climate change. The fund has raised over USD 10 billion since 2014, and has directed resources to projects dedicated to both mitigation and adaptation. Through partnering with a number of international organisations, NGOs, and private sector companies, the fund has helped build resilience for an estimated 350 million people worldwide. Special Climate Envoy John Kerry recently stated that the United States would recommit to the Fund as part of renewed efforts to support global climate finance.

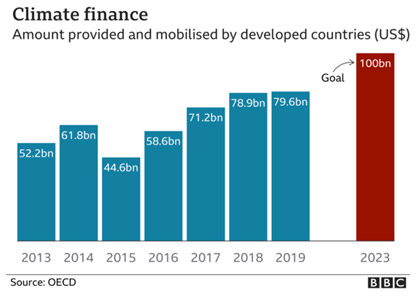

Over a decade ago, developed countries promised to mobilise USD 100 billion a year by 2020 to help poor countries deal with the worst impacts of global warming and invest in green energy sources. In 2019, rich nations raised USD 80 billion for climate action but mostly on commercial terms. In November 2021 U.S. President Joe Biden pledged to double his contribution to USD 11.4 billion, but that money is for 2024 and hasn’t been approved by Congress.

Rich countries now estimate they have raised between $88 billion and $90 billion annually, and are seeking to reach the $100 billion goal in 2022.[xxii] Truth be told, there is no paucity of resources in the developed world—only a lack of political will.

Conclusion

The solution to the climate challenge is innovation and technology, especially green technology. Significant initiatives have been taken in the last few years. Green banks are being set up. Buildings are going green. Green energy or renewable energy, especially solar, has become the cheapest to install, generate and maintain. Even more significantly, the employment opportunities being created in establishing renewable energy facilities are more than conventional energy. But as noted above, this is just a beginning and the journey ahead is far more uphill. Availability of climate finance on soft terms is critical for the success of mitigation and adaptation measures by developing nations. The difficulty is that the need for climate justice does not weigh on the conscience of the western world.

A sticking point which has angered the poorer nations is the failure of rich countries to make good on their promise. The poorer nations rightly state that they cannot cut emissions faster without the cash. As per the figures collated by the OECD, almost no progress has ben made between 2018 and 2019.[xxiii] It is quite evident that despite the tall talk and half-hearted commitments to help the developing countries in adapting to climate change, the rich countries will try to get away with as little as possible. As most of the growth will come from emerging markets and the least developed countries, it would be efficacious if they transition straight away to Green Technologies and energy, instead of crossing the pit in two leaps, which would entail delays and higher costs. Lack of money cannot be held as an excuse. The pandemic has shown that governments can find money where necessary.[xxiv]

While some amount of finance and green technologies will be contributed by the affluent nations, realistically, the heavy lifting will have to be done by the developing countries themselves, from their own resources. And in reality, they have no choice, as the cost of neglecting climate action will be too high to bear.

A holistic approach will have to be followed entailing action and changes in every sphere especially lifestyle; aggressive recycling and cutting down on waste; creating environmental consciousness at home, school and public space; reducing and eventually eliminating green premium; increasing R&D budgets for innovation in green technologies; information exchange, adoption of best practices, imposing penalties like carbon tax and providing incentives for adoption of green practices.

Author Brief Bio: Amb. Vishnu Prakash, has served as High Commissioner to Ottawa, Ambassador to Seoul, Official Spokesperson of Foreign Office and Consul General to Shanghai. He has also done postings in Moscow, New York, Vladivostok, Tokyo, Islamabad and Cairo. Since retirement in Nov. 2016, he has turned a foreign affairs analyst & commentator, with special focus on the Indo-Pacific region

References:

[i] Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi at COP26 Summit in Glasgow http://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/34466/national+statement+by+prime+minister+shri+narendra+modi+at+cop26+summit+in+glasgow

[ii] Shyam Saran, How India Sees the World: From Kautilya to the 21st Century

[iii] Fall in CO2 emissions https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-59016075

[iv] Greenhouse Gas Bulletin: Another Year Another Record https://shar.es/aWzs9E

[v] https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/17/worlds-population-is-projected-to-nearly-stop-growing-by-the-end-of-the-century/

[vi] Shivshankar Menon, “India and the Asian geopolitics: The Past, Present”, Penguin, pp 329

[vii] What is COP26 and why is it important? https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/09/what-cop26-and-why-it-important?CMP=share_btn_tw

[viii] CAT Climate Target Update Tracker https://climateactiontracker.org/climate-target-update-tracker/

[ix] https://www.britannica.com/science/greenhouse-gas

[x] https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions.html

[xi] Climate Change and the Developing World: A Disproportionate Impact: https://www.usglc.org/blog/climate-change-and-the-developing-world-a-disproportionate-impact/

[xii] India among top 10 countries with higher climate performance: Report http://www.ecoti.in/nqj18a

[xiii] Net-zero presents many opportunities for India — and challenges https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/net-zero-presents-many-opportunities-for-india-and-challenges/

[xiv] Vivekananda International Foundation webinar of 22 November 2021: Talk by Dinkar Srivastava

[xv] HTLS 2021: India’s energy growth from scarcity to justice to security https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/htls-2021-india-s-energy-growth-from-scarcity-to-justice-to-security-101637607948586.html?utm_source=twitter

[xvi] In the pandemic, India’s middle class shrinks and poverty spreads while China sees smaller changes https://pewrsr.ch/3eP3Fih

[xvii] Solar is now ‘cheapest electricity in history’, confirms IEA https://www.carbonbrief.org/solar-is-now-cheapest-electricity-in-history-confirms-iea

[xviii] Note 14.

[xix] Green buildings represent one of the biggest investment opportunities of the next decade https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/a6e06449-0819-4814-8e75-903d4f564731/59988-IFC-GreenBuildings-report_FINAL_1-30-20.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=m.TZbMU

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Note 1.

[xxii] Climate finance https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-05/rich-countries-fall-10-billion-short-in-climate-finance-pledges

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] Climate Change: The Slow Motion Pandemic http://www.iesve.com/discoveries/blog/8579/climate-change-slow-motion-pandemic