Introduction

The idea of connecting the Pacific and the Indian Oceans emerged during Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s speech in the Indian parliament in 2007[i]. He emphasised the idea because he wanted to highlight the importance of India. The “Indo-Pacific” is the concept instead of the “Asia-Pacific,” which did not include India. Recently, improved cooperation between India and Japan has become more evident. India and Japan have been increasing their diplomatic exchanges, joint exercises of their armed forces, and seeking joint infrastructure projects. However, deep India-Japan relations have not always naturally occurred because of geographical and geopolitical distance. For example, according to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, 37,933 non-resident Indians (NRIs) live in Japan (MEA). And Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs points out that about 9,838 Japanese lived in India in 2018.[ii] However, 1,280,000 NRIs and 446,925 Japanese are living in the US. 241,000 NRIs and 98,436 Japanese are living in Australia. And 55,500 NRIs and 120,076 Japanese live in China. Compared with these numbers, India and Japan have relatively few people-to-people exchanges. Therefore, it is logical to ask why the relations of India-Japan have progressed recently.

India-Japan relations have grown closer since end of the 2000s, when China’s activities began to grow and were perceived as a threat to India and Japan. And India-Japan security relations have developed faster than economic relations. In addition, India-Japan bilateral relations have developed alongside multilateral relations, including with the US and Australia. As a result, this article focuses on the China factor in India-Japan relations and looks at three issues: What has happened since 2000s? What can India-Japan cooperation do? And, how does India-Japan cooperation affect relations with the US and Australia?

What has happened?

Let us take a look at three areas: The sea around Japan, the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean

The Sea around Japan

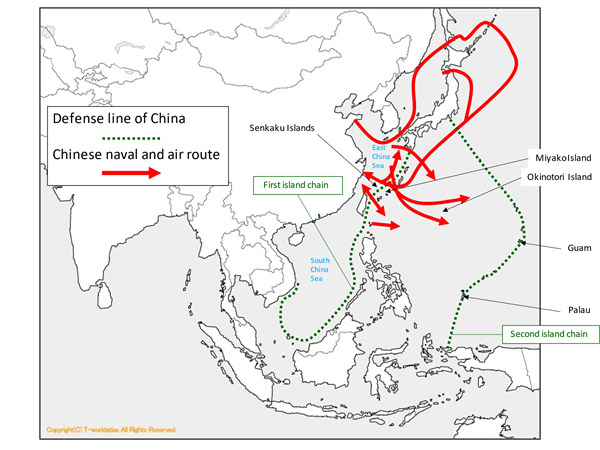

For Japan, the Chinese submarines are a threat to Japan’s SLOCs in the Indian Ocean. But at the same time, the main concerning points are China’s activities in the sea around Japan. For some years now, Beijing has been expanding its military activities near Japan. For example, in 2004, a Chinese nuclear attack submarine violated Japan’s territorial seas in the East China Sea. China has also been carrying out naval exercises on the Pacific side of Japan since 2008, as is show in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: China’s naval and air activities around Japan

Source: Ministry of Defense of Japan, 2020

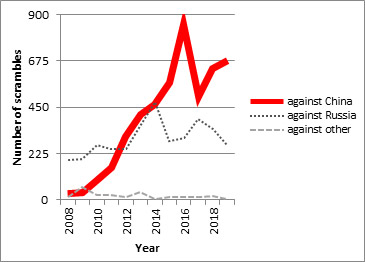

The Chinese air force has also been expanding its activities. In 2013, Japan’s Ministry of Defense white paper pointed out that, “in FY 2012, the number of scrambles against Chinese aircrafts exceeded the number of those against the Russian aircrafts for the first time.” In 2016, the number of scrambles against Chinese aircraft further increased to 851. This decreased to 500 in FY 2017, but the number rose to 638 in FY 2018 and 675 in FY 2019 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of scrambles of Japan’s Air Self-Defense Force

Source: Joint Staff, Ministry of Defense of Japan, 2020

The South China Sea

From Japan’s point of view, the situation in the South China Sea is a serious matter. While in 2016 the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague rejected China’s claim to ownership of 90 percent of the South China Sea, Beijing is ignoring the verdict and building three new airports on seven artificial islands in the South China Sea. This has provoked Japanese concern, and Prime Minister Abe, in an article published in 2012, just two days before he was sworn in as prime minister, noted that, “increasingly, the South China Sea seems set to become a ‘Lake Beijing,’ which analysts say will be to China what the Sea of Okhotsk was to Soviet Russia: a sea deep enough for the People’s Liberation Army’s navy to base their nuclear-powered attack submarines, capable of launching missiles with nuclear warheads”[iii]. His statement pointed out to the possibility of China deploying ballistic missile submarines under the protection of fighter jets launched from these artificial islands, and excluding all foreign ships and airplanes that might identify their submarines.[iv] Abe pointed out that, “if Japan were to yield, the South China Sea would become even more fortified.”[v]

The Indian Ocean

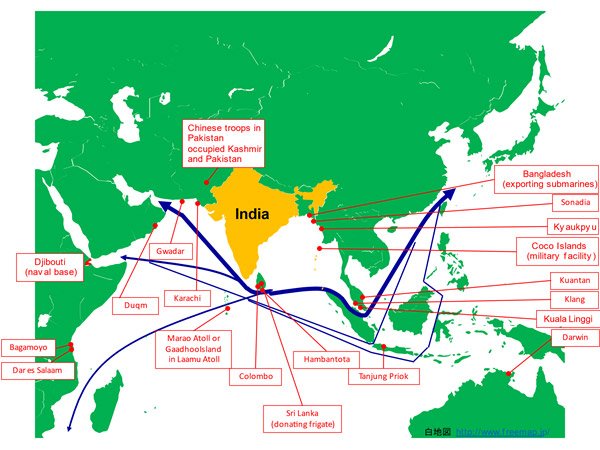

China has expanded its activities in the Indian Ocean, which has caused concern for India. Beijing insisted on solving its “Malacca Dilemma”—that it must avoid excessive dependence on the Malacca Strait, which is a strategic shipping lane for China’s oil and is controlled by the US Navy. As a result, China is creating alternative routes such as a Middle East-Pakistan-Xinjiang Uyghur route and a Middle East-Myanmar-China route. These are a core part of China’s Belt and Road Initiatives.

On one hand, Beijing is investing in developing ports such as Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Chittagong in Bangladesh, and Kyaukpyu in Myanmar in the Indian Ocean. Because of the sheer size of China’s investments and the 6-8 percent interest rates it charges on loans, these countries now have enormous debts (the World Bank and Asia Development Bank, in contrast, charge 0.25-3 percent).[vi] With Hambantota, Sri Lanka was unable to repay its loan. It thus became a victim of China’s “debt diplomacy” and in December 2017 handed over the port to China as part of a 99-year lease agreement.

In the meantime, in order to secure sea routes, China has started to expand its military forces in the region. China expanded its military activities in the Indian Ocean since 2009, when it joined anti-piracy measures off the coast of Somalia. Chinese submarines have patrolled since 2012, and the Chinese surface fleet has called at ports in all the countries around India, including Pakistan, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. According to Admiral Sunil Lanba, Chief of Naval Staff, Indian Navy, Beijing has deployed 6-8 warships in the Indian Ocean,[vii] while in Pakistan, it has started to deploy ground forces. Referring to China’s operation of the Hambantota port, some raise concerns that if the Chinese navy begins to use civil-purpose ports as naval supply bases, China could overcome its weakness, which is its lack of a naval port in the region.

In addition, China also exports submarines to countries around India. Bangladesh received two in 2016, and Pakistan decided to import eight Chinese submarines for its navy. In particular, Islamabad’s willingness to possess nuclear submarines must not be overlooked. Because it lacks the technology, there is a reasonable possibility that China will support such “indigenous” nuclear submarines to counter India.

The activities of these submarines indicate that they could potentially attack India’s nuclear ballistic missile submarines, aircraft carriers, and sea lines of communication (SLOCs). This means that these submarines will, to a great extent, regulate India’s activities (Figure 3).

Figure 3: China’s activities in the Indian Ocean

Source: author

The India-China border area

Since 2000, China has been developing infrastructure projects in the India-China border area, increasing the number of strategic roads, trains, tunnels, bridges, and airports. The military balance in the India-China border is changing because of China’s rapid military infrastructure modernisation. Along with these infrastructure projects, Beijing has started to deploy more armed forces in the area. In 2011, India recorded 213 incursions in the India-China border area, but in the following years, the numbers were larger: 426 in 2012, 411 in 2013, 460 in 2014, 428 in 2015, 296 in 2016, 473 in 2017, 404 in 2018, and 663 in 2019.

China is deploying troops in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and Pakistan where a part of the China-Pakistan economic corridor, which is a core project of the Belt and Road Initiative, is situated.[viii] Beijing is also developing infrastructure projects to connect to Nepal. It has entered the Doklam heights, claimed by both China and Bhutan, insisting on building a new road to deploy more forces. This led to Indian and Chinese armed forces facing each other in a standoff along the 3,500 km India-China border (including the Line of Actual Control, a line separating the territory controlled by India from the territory controlled by China).

And in 2020, the situation escalated further. China entered the India side in the spring and the two sides clashed in June. At least 20 Indian soldiers sacrificed their lives (the Chinese did not publish any losses). After that, China continued to redeploy fighter jets and missiles from other areas of China. For example, China moved H-6 bombers that can employ cruise missiles from Wugong to Golmud and Kashgar[ix]. China also deployed DF-21 missiles to Kailash Mansaravar[x] (DF-21s use new types of warheads that the US and Japan cannot intercept through missile defense systems). At the Hotan air base, China has been increasing heavy fighters and bombers such as the J-11 and J-16. Also at the Hotan base, many other types of military aircraft such as the Y-8G electronic reconnaissance aircraft, the KJ-500 early warning aircraft, and the CH-4 drone were present.[xi] The latest J-20 stealth fighter jets are also deployed.[xii] To protect these airfields and missiles, China is deploying Su-300 surface-to-air missiles.[xiii] To deal with China’s build-up, India has repeatedly conducted missile tests. In six weeks (September to October), India conducted more than 12 missile tests.[xiv]

What can India-Japan cooperation do?

What effect can India-Japan cooperation have on this kind of Chinese aggression? If history is any guide, the motive behind China’s maritime expansion is based on military balance. For example, when France withdrew from Vietnam in the 1950s, China occupied half of the Paracel Islands. In 1974, immediately after the Vietnam War ended and the US withdrew from the region, China occupied the other half. In 1988, after the Soviet withdrawal from Vietnam, China attacked the Spratly Islands, controlled by Vietnam. Along similar lines, after the US withdrawal from the Philippines, China occupied Mischief Reef, claimed by both the Philippines and Vietnam (Ministry of Defense of Japan, 2020). Whenever China found a power vacuum created by a changing military balance, it exploited it and expanded its territories. Maintaining a military balance to avoid creating a power vacuum will counter China’s strategy. And if India and Japan (and the US and Australia) cooperate with each other, there are at least three methods to maintain military balance.

The India-China border and the East China Sea

First, we should focus on the linkage of the India-China border area and the East China Sea. For example, if India cooperates with Japan (and the US), India will not need to deal with all the Chinese fighter jets and missiles at once because China is likely to keep some of its fighter jets and missiles in its east side against Japan, and vice versa. China’s defence budget is also divided among its east front against Japan and its southern front against India. Therefore, by using its know-how of high-end military infrastructural development, Japan can support India’s efforts to modernise its defence in the India-China border area. Since 2014, Japan has invested in India’s strategic road project in the northeast region of India. By using this road, the Indian army can deploy more forces and supplies to the border area. And as mentioned above, in 2018, India and Japan started joint development of unmanned ground vehicles. These unmanned ground vehicles are useful along the India-China border where conditions are too harsh for people to stay in the winter.

In addition, India-Japan cooperation can have some effect in the event of an India-China crisis. Dispatching the Izumo-class helicopter carrier with a US aircraft carrier during the Malabar Exercise in 2017, and the statement of support for India from the Japanese ambassador, achieved good results in the Doklam crisis in 2017.[xv] A similar situation occurred in 2020. Japan can use similar measures in a future crisis. In addition, as a good means to dissuade China, Japan should draw China’s attention toward Japan instead of toward India. For example, if Japan deployed the Self Defense Forces (SDF) in the Senkaku Islands, China would deploy more forces to Japan rather than to India.

The security burden in the Indian Ocean

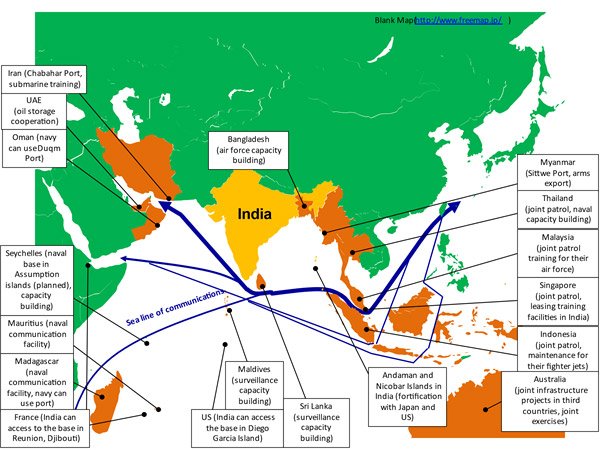

Second, if India has the will and capabilities, Japan, US and Australia will be able to release themselves from the heavy burden to safeguard security in the Indian Ocean and can deploy more military force in the East China Sea and the South China Sea to maintain military balance. And India can set the key role in the Indian Ocean. Recently, India has shown its presence actively (Figure 4). India will be a new hope for Japan. Japan should share the know-how related to anti-submarine capabilities and enhance India’s capability as a security provider. In the “Japan-India Joint Statement Toward a Free, Open and Prosperous Indo-Pacific” in September 2017, “They noted the ongoing close cooperation between the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) and the Indian Navy in various specialised areas of mutual interest, including anti-submarine aspects.”[xvi]

Figure 4: India’s presence in the Indian Ocean

*The figure was made by the author

India-Japan infrastructure cooperation is a useful method to neutralise China’s influence in the Indian Ocean Region. The Hambantota port in Sri Lanka had no alternative to a “debt diplomacy” offer from China: the threat of sanctions and war crimes charges in the wake of Sri Lanka’s civil war meant that China was the only country willing to provide it with massive investment. Beijing thus created a huge debt for Sri Lanka. This enabled Beijing to negotiate the 99-year lease of the Hanbantota port. India and Japan should offer an alternative. For example, Bangladesh has already chosen Japan’s Matarbari port project instead of China’s Sonadia project (Figure 5), and thus it is possible that India and Japan can use a similar tactic.

Supporting Southeast Asia

Third, Japan and India can collaborate to support Southeast Asian countries around the South China Sea, which need to beef up their defence with a trustworthy partner that provides military support. Thus, Japan and India should collaborate with each other and support these countries more effectively. For example, Japan and India can collaborate to support Vietnam.

For India, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are a gateway to connect with Southeast Asia. These islands are strategically important, as they are near the Malacca Strait and SLOCs. As described above, China’s submarines venture into the Indian Ocean, sailing from China’s Hainan Island through the South China Sea and choke points including the Malacca Strait. Therefore, to track China’s submarine activities, the Andaman–Nicobar Islands are an excellent location. India is modernising its infrastructure to deploy large warships, patrol planes, and transport planes in the Andaman-Nicobar Islands. No detailed official report has been published, but some media reports indicate that India, Japan, and the US are planning to install a submarine detecting sensor system along the coastline of the Bay of Bengal.[xvii] Japan has also decided to support radar facilities and power plants in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Japan is also planning to build a light fibre cable connection between mainland India and these islands. Although these are civil projects to resolve electric power shortage difficulties, there is a high probability that the project will have strategic effects related to China.

Impact of India-Japan Cooperation on Relations with the US and Australia

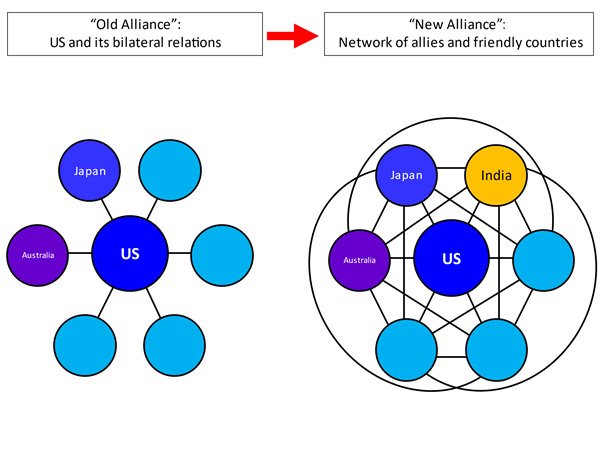

As mentioned above, India-Japan cooperation has been a core part of the US-led security framework in the Indo-Pacific. And that framework itself has changed. After World War II, the “hub and spoke system”—US alliances with countries such as Japan, Australia, the Philippines, and South Korea—maintained order in the Indo-Pacific (Figure 5). Although the US formed alliances with many countries in East Asia, a close defence relationship was lacking among its allies. For example, both Japan and Australia are US allies, but during the Cold War, there were no close security relations between Japan and Australia. In such a context, Japan and Australia are dependent on US military power and information. The hub-and-spoke system would function effectively if the US had enough military resources to tackle all the problems in this region.

However, a salient feature of the recent security situation is the changing US–China military balance. For example, during 2000-19, the US commissioned 21 new submarines. During the same period, China commissioned at least 54 submarines. US allies and friendly countries need to fill the power vacuum to maintain military balance. As a result, a new security framework has emerged. This new framework is a security network of US allies and friendly countries, and includes not only US-led cooperation, but also India-Japan-Australia, India-Japan-Vietnam, India-Australia-Indonesia and India-Australia-France, all of which do not include the US. In this case, India-Japan security cooperation will be the key.

Figure 5: Old alliance and new alliance

Source: Satoru Nagao, “The Japan-India-Australia ‘Alliance’ as Key Agreement in the Indo-Pacific,” ISPSW Strategy Series, September 2015,

https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/193713/375_Nagao.pdf

Conclusion

Why have India-Japan relations progressed recently? As mentioned above, this article focuses on the China factor in India-Japan relations. And China has been escalating its assertive behaviour against both India and Japan. Maintaining military balance is vital to curbing China’s activities. To do this, a new type of the Indo-Pacific security framework is establishing itself, one in which India-Japan cooperation plays a vital part.

What kind of tasks will India-Japan cooperation face? In light of the above analysis, there are at least three. First, it is important to deal with China’s economic strength. Because China has enough money, it can modernise its military very rapidly. Because China has enough money, it can create debt in developing countries by leveraging the infrastructure projects of the Belt and Road Initiatives. Curbing the income of China will thus be vital. India’s rising economy and Japan’s number three world economic status could create an alternative market to China if there is enough cooperation. But the supply chains of both countries are still very dependent on China. How to solve these difficulties will be an important challenge for India-Japan cooperation.

Second, under escalating US-China competition, the US has tried to institutionalise Quad cooperation. But compared with Europe, the Indo-Pacific region is far wider and more diverse. If one includes the sea between Indonesian islands, the size of the Indo-Pacific region is similar to that of the EU. How to institutionalise the framework will be the challenge for all involved countries, including India and Japan.

Third, opposition to China cannot be the only reason that India and Japan are connected. Therefore, for the long-term success of India-Japan cooperation, the two countries need to find another reason to maintain cordial and deep relations. During the Cold War, India-Japan relations did not develop well, and without strong efforts, their relations could return to that state. India-Japan relations have been developing at a very fast pace lately. This is the best chance for both India and Japan. Now is the time to act.

Author Brief Bio: Dr. Satoru Nagao is a Fellow (Non-Resident) at Hudson Institute, based in Tokyo, Japan. From December 2017 through November 2020, he was a visiting fellow at Hudson Institute, based in Washington, D.C.

[i] Shinzo Abe, “Confluence of the Two Seas,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, August 22, 2017,

https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

[ii] Ministry of External Affairs of Japan, Population of Overseas Indians,

https://mea.gov.in/images/attach/NRIs-and-PIOs_1.pdf

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Kaigaizairyuuhoujinnsuu (Japanese), November 13, 2019,

https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/toko/page22_000043.html

[iii] Shinzo Abe, “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond,” Project Syndicate, December 27, 2012, http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe#Vd6yytDokZJCiwtv.01

[iv] Satoru Nagao, “Nightmare Scenario in the South China Sea: Japan’s Perspective,” Maritime Issues, September 12, 2019,

Yoshida, Reiji, “Beijing’s Senkaku Goal: Sub ‘Safe Haven’ in South China Sea,” The Japan Times, November 7, 2012,

[v] Shinzo Abe, “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond,” Project Syndicate, December 27, 2012, http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe#Vd6yytDokZJCiwtv.01

[vi] Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “China May Put South Asia on Road to Debt Trap,” Economic Times, May 2, 2017,

[vii] “China’s Growing Presence in Indian Ocean Challenge for India: Navy Chief,” NDTV, March 14, 2019, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/chinas-growing-presence-in-indian-ocean-challenge-for-india-navy-chief-2007615

[viii] “Chinese Army Troops Spotted Along Line of Control in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir,” The Economic Times, July 12, 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/chinese-army-troops-spotted-along-line-of-control-in-pakistan-occupied-kashmir/articleshow/51380320.cms

Manish Shukla, “China Deploys Troops in Sindh, Just 90 Km away from Indo-Pak Border,” Zeenews, March 21, 2019,

[ix] Vinayak Bhat, “Massive deployment at China’s airbases, aerial exercises underway,” India Today, October 4, 2020,

[x] “Amid border tensions with India, China constructs missile site at Kailash-Mansarovar,” The Economic Times, August 31, 2020,

[xi] Michael Peck, “China Has Doubled Its Fighter Jets On India’s Border,” Forbes, August 10, 2020,

[xii] Sutirtho Patranobis, “China’s J-20 fighter jets near India border? State media downplays report,” Hidustan Times, August 19, 2020,

[xiii] Mayank Singh, “Massive Chinese build-up along Line of Actual Control,” The New Indian Express, August 27, 2020,

[xiv] Sushant Kulkarni, “Explained: Why has the DRDO recently conducted a flurry of missile tests?” The Indian Express, October 21, 2020,

[xv] “Doklam stand-off: Japan backs India, says no one should try to change status quo by force,” The Times of India, August 18, 2017,

“Don’t bank on US and Japan, you’ll lose: Chinese daily warns India over Doklam standoff,” Business Today, July 21, 2017,

[xvi] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Japan-India Joint Statement: Toward a Free, Open and Prosperous Indo-Pacific, September 14, 2017, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000289999.pdf

[xvii] Singh, Abhjit, “India’s ‘Undersea Wall’ in the Eastern Indian Ocean,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, June 15, 2016,

https://amti.csis.org/indias-undersea-wall-eastern-indian-ocean/