Introduction

The Union Budget, which is an annual report on the government’s revenue and expenditure, is often perceived as a platform for major policy announcements. However, it actually accounts for a decreasing share of public expenditure, with much more spending happening at the state level. As a result, State Budgets deserve more attention and scrutiny. The hype around the Union Budget stems from a bygone era when taxes changed frequently, and people were eager to know how prices would be affected. However, stability and predictability are essential for tax reform. While there may be a need to simplify the GST and reduce the number of tax rates, this is the responsibility of the GST Council, not the Union Budget.

The current budget is a stark contrast to N.D. Tiwari’s “sindoor budget” of 1988-89 made headlines for its symbolic tax exemptions on items like sindoor and kajal. Instead, this budget is all about empowering women, youth and progress. The government is gearing up for the ‘Amritkaal’, charting a path towards a developed India by 2047. It’s a budget focused on real change and investment in the future, leaving the quaint symbols of the past behind. This is a budget for a new India, ready to embrace its destiny and unleash its full potential.

The Finance Minister encountered a nuanced predicament in navigating the current economic terrain. Mindful of the importance of upholding macroeconomic stability, the budget strikes a delicate equilibrium between tackling inflationary constraints and promoting economic growth hindered by external factors. This conundrum entailed a precarious balancing act, which necessitated the Finance Minister to display unwavering composure.

The art of budgeting is a crucial component in fulfilling the commitment to proficient and impactful governance. Substantial deviations in the projection of revenue and expenses can impede the execution of government initiatives and policies, ultimately jeopardising social welfare results. Against this background, we highlight four areas where the budget has done exceptionally well.

Fiscal Discipline

Democratic political systems often face choices between present and future welfare. According to Nordhaus’ influential work published in 1975 on the political business cycle, a democracy that evaluates political parties solely based on their past performance is likely to make decisions that are unfair to future generations. This is because politicians may prioritise short-term gains over long-term benefits in order to secure immediate political success. Nordhaus (1975) further goes on to say, “within an incumbent’s term in office, there is a predictable pattern of policy, starting with relative austerity in early years and ending with the potlatch right before elections” (pp.187)[1].

Hence, the political business cycle theories posit that incumbent political parties engage in opportunistic behaviour, manipulating economic instruments before elections to enhance their chances of being re-elected. In other words, Governments are known to employ a strategic approach by exploiting the short-term Phillips curve to further their objectives[2]. In addition, governments may also take advantage of the limited knowledge and simplistic expectations of voters in order to attain their goals. This reveals a complex interplay between political manipulation and the economic implications of short-term policies.

At the same time, the work of Rogoff (1990) and Rogoff and Sibert (1988) suggests that in situations where information about the competence of an incumbent is limited, expansionary policy measures implemented prior to an election are often viewed as an indicator of high competence[3]&[4]. As per their analysis, a potential outcome of the political business cycle could be an increase in the budget deficit, as well as an increase in the money supply via the monetisation of the deficit. In addition, there may also be an increase in inflation during the electoral period, as politicians prioritise short-term economic gains in order to increase their chances of re-election. In the case of India, too, some studies have found clear evidence of an increase in revenue deficit in the years leading to an election[5].

However, under the incumbent government in India, things have changed. What Narendra Modi’s government is doing is completely opposite to the basic tenets of the political business cycle theories. The Prime Minister has proved Nordhaus and other PBC theorists wrong.

With the upcoming elections, many expected the government to unleash a spree of spending, showering voters with loan waivers and other financial goodies. But the Finance Minister and the government have taken a different approach, choosing to prioritise long-term stability over short-term gains. By resisting the temptation to indulge in vote-winning measures, the government has demonstrated a commitment to responsible financial management, even in the face of political pressure. This budget stands as a testament to the government’s determination to put the country’s future first.

The government has demonstrated exceptional fiscal discipline in recent years, consistently meeting or exceeding its deficit target. India’s fiscal deficit shot up to a record 9.3% in 2020/21, from 4.6% the previous year due to pandemic-related spending. This year, despite formidable fiscal challenges owing to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict and global economic uncertainties, the government deserves accolades for reinforcing its resolve to stick to the fiscal deficit target of 6.4%.

For the next year, the government has committed to bringing down the fiscal deficit to 5.9%. This reduction is in line with the government’s earlier commitment towards the fiscal deficit target of 4.5% of GDP by the end of 2025/26. Obviously, this doesn’t have to be linear. Even if the reduction is by 0.5% next, there may be more opportunities for substantial consolidation and growth as the global recession and headwinds would be behind us in the first year of the next government. Thus, there will be more room for fiscal consolidation in the next two years.

The endeavour to simultaneously achieve rapid economic growth and social welfare improvement while maintaining responsible fiscal management is a multifaceted challenge. Nevertheless, recent studies indicate that the fundamental means of accomplishing these goals is not merely through the reduction of fiscal deficits but rather by diminishing expenditures of inferior quality. This necessitates abstaining from the temptation to artificially generate capital account surpluses that come at the cost of enlarging gross fiscal deficits.

Capital Expenditure

In the midst of the Great Depression in 1933, economist John Maynard Keynes penned a passionate letter[6] to President Roosevelt urging him to take bold actions to jumpstart the economy. Keynes argued that the government should borrow money and use it to increase spending rather than raise taxes, as a way to boost national purchasing power and ignite growth. While it’s unclear if Roosevelt actually read the letter, he did ultimately turn to government spending to revitalise the economy through his New Deal.

A lot has already been written about the union government setting aside ₹ 10 lakh crore (~3.3% of the country’s GDP) for Capital Expenditure in this budget, a 37.4% increase from last year’s Revised Estimates. Economists talk about the multiplier effect. The multiplier effect is a concept that highlights the exponential impact of changes in government spending on a nation’s output. When the fiscal multiplier is greater than one, an increase in government spending leads to a corresponding increase in output that is greater than the original investment. In simpler terms, a single rupee increase in government spending could result in a return that is worth much more than one rupee.

The economic survey may have shed light on the resurgence of private investment, but with global challenges and monetary constraints, it alone may not be enough to drive growth. This is where the government steps in, with their unwavering commitment to revive the economy demonstrated by allocating a record-high ₹ 10 trillion for long-term capital expenditure in 2023-2024, surpassing the previous year’s budget of ₹ 7.5 trillion, thus providing a cushion from global headwinds. A 33% increase year-on-year shows that the government is putting their money where its mouth is and that growth is within reach. This, in turn, will also help in crowding in private investments.

But what is the extent of the fiscal multiplier in the case of capital expenditure in India? There is a dearth of studies on the subject. However, the most influential study out of these is that by Bose & Bhanumurthy, which first came out as a NIPFP Working Paper in 2013 and later got published in the Journal of Applied Economic Research[7]. According to their calculations, the multipliers for capital expenditures, transfer payments, and other revenue expenditures are 2.45, 0.98, and 0.99, respectively. However, the multipliers for taxes are approximately -1. Goyal & Sharma (2018) find that capital expenditure exhibits the greatest cumulative multiplier, with a size ranging from 2.4 to 6.5 times that of revenue expenditure.

Furthermore, capital expenditure has a more pronounced impact on long-term inflation reduction. Nonetheless, capital expenditure is susceptible to greater volatility due to its vulnerability to discretionary spending cuts[8]. However, the multipliers of public capital expenditure would not be as high as they used to be in 2013. The explanation for this phenomenon is straightforward. During the past nine years, the government has made significant expenditures on infrastructure development, including roads, railways and logistics. Infrastructure no longer poses as significant an obstacle for private capital influx as it did during the UPA era. Thus, the government is not just focusing on capital expenditure but also on addressing institutional weaknesses.

At the same time, the capital expenditure multipliers of the states are much higher the that of the union government’s capital expenditure. Thus, it is crucial to encourage states to prioritise capital expenditure as a means to revitalise the economy, especially after the shocks[9].

Incentivising States for Capital Expenditure

In pursuit of fostering cooperative fiscal federalism, the Union Government has extended a program of financial assistance program for capital expenditure for the upcoming fiscal year of 2023-24. This initiative has received a significant boost in allocation, with an increased budget of 1.30 lakh crore, representing a 30% escalation from the previous year. In terms of the current fiscal year, this amounts to approximately 0.4% of the nation’s GDP. The importance of empowering the states to undertake capital projects cannot be overstated, and this expanded allocation represents a progressive step forward.

The FM has decided to continue a 50-year interest-free loan to the state governments for one year. The states have been given autonomy to spend this at their discretion, with a catch – a portion of it is contingent upon increasing their actual capital expenditure. But what will they spend it on? The Union Government has tied parts of the outlay to either reforms or allocation to priority areas. This includes urban planning reforms, financing reforms in ULBs to make them creditworthy, the State share of capital expenditure of central schemes etc. Thus, there will be an inherent incentive for the state governments to also ensure the quality of public expenditure.

However, states should focus on the quality of the capital expenditure. There is a significant variation in capital expenditure by different states. Delving into the granular details, the states of Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu collectively contribute over 40% towards the consolidated capital outlay carried out by all states. In a particularly fascinating trend, states such as Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Assam and Jharkhand exhibit a relatively larger proportion of capital outlays in relation to the size of their respective economies.[10]

Similarly, the RBI’s State Finances report has also pointed out that fiscal marksmanship relating to capital outlay also varies across the state. During 2017-18 to 2019-20, states & union territories like Andhra Pradesh, Delhi, Jammu & Kashmir, Goa, Tripura and Punjab have cut their budgeted capital expenditure by more than 40%. Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, and Nagaland were the sole outliers in exceeding their budgeted targets for capital expenditure.

The RBI report has also flagged the issue of a residual approach to spending. Over the past five years, a substantial portion, amounting to one-fourth, of total expenditures occurred solely during the month of March. This presents a grave matter as the primary objective of spending by the year’s end results in a compromise in the quality of expenditures. The Union budget can only nudge the states to improve their quality of public expenditure. But under a federal structure, states will have to do more if they want to ensure higher growth rates for a prolonged period.

Transparency

In the past two budgets, the government has taken bold steps to bring off-budget borrowings, like those of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) previously, in its own light. By doing so, they aim to offer a clear picture of the government’s financial obligations, enabling informed decisions and assessments. Previous finance ministers acknowledged the issue with off-budget borrowings and made hollow announcements which were never fructified. P. Chidambaram, in his budget speech (2008-09), stated – “I acknowledge that significant liabilities of the government on account of oil, food and fertilizer bonds are currently below the line. This accounting arrangement is consistent with past practice. Nevertheless, our fiscal and revenue deficits are understated to that extent. There is a need to bring these liabilities into our fiscal accounting.” However, it was Nirmala Sitharaman who made it a reality. The finance minister has continued with this tradition again this year.

Social Sector

Some have argued that the union government’s outlay on the social sector, as a percentage of its overall expenditure, has displayed a persistent stasis. In FY 2009-10, the government allocated 21% of its total expenditure towards social sector expenditures, which subsequently saw a slight decrease to 20% by FY 2019-20. Over the past fourteen years, the average proportion of social sector spending by the government, amounting to nearly one-third (30%), was dedicated to the provision of subsidised food to the country’s poorest two-thirds. However, the percentage of such spending exceeded 50% in FY 2020-21 amidst the global health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the percentage of overall expenditure on the social sector would have remained same in the last few years, there is an incremental improvement on quality of expenditure in the social sector. Notably, today, intended beneficiaries get 100% of funds which they are supposed to get. During a visit to the drought-stricken Kalahandi district in Odisha in 1985, Rajiv Gandhi made a statement indicating that only 15 paise out of every rupee spent by the government actually reached the intended recipient. One should quote Justice A. K. Sikri’s majority opinion on the constitutionality of the Aadhar Act: “Resultantly, lots of ghosts and duplicate beneficiaries are able to take undue and impermissible benefits… It cannot be doubted that with UID/Aadhaar much of the malaise in this field can be taken care of.”[11]

The digital public infrastructure has not only enhanced accessibility of public services to the most disadvantaged and susceptible sections of the nation, but it has also facilitated the detection and elimination of fraudulent beneficiaries from various government schemes. The system has effectively curbed leaks caused by non-existent and duplicate beneficiaries who use fake identities to obtain benefits. While one should acknowledge that there are some exclusion errors, but the government is ensuring that there are enough safeguards against exclusion in the cases of authentication failure. The digital public infrastructure and Aadhaar based biometric authentication (ABBA) also makes it easier to ensure portability of benefits.

More importantly, use of Aadhaar to identify and authenticate beneficiaries in government scheme has led to considerable fiscal savings. Thus, even if the social sector spending has remained stagnant, the use of DPI and ABBA, has ensured that more people, especially the one who are marginalised and vulnerable are able to get intended benefits.

Moreover, criticism has been raised regarding the allocation of funds for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) scheme in the 2023-24 budget. The budget for MGNREGA in 2023 is 18% lower than the budget estimates of Rs. 73,000 crore for the current year of 2022-23, and approximately 33% lower than the revised estimates of Rs. 89,000 crore for the current year.

MGNREGA operates on a demand-driven model where households seeking employment are entitled to a minimum of 100 days of unskilled manual labor during a given financial year. In the ongoing fiscal year of 2022-23, nearly all rural households, or 99.81%, have been offered wage employment according to their demand. If a job seeker does not receive employment within 15 days of application, they are eligible for a daily unemployment allowance as per the provisions of the Scheme.

As there is reduced demand of MGNREGA, the number of person days generated by MGNREGA has also been going down. While the person days generated under MGNREGA was 389.09 crore in FY20-21 due to the migration to rural areas owing to pandemic, it has been going down subsequently.

| FY2022-2023 | FY 2021-22 | FY2020-21 | FY 2019-20 | |

| Person days generated (in crores) | 248.08 | 363.33 | 389.09 | 265.35 |

Source: Ministry of Rural Development[12]

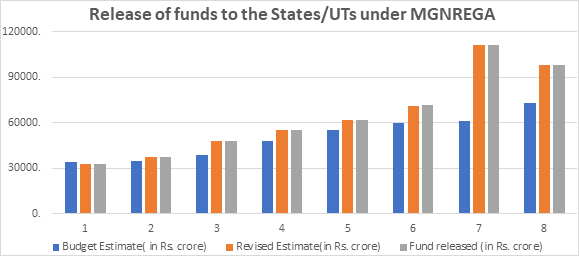

It should also be highlighted that the budget estimates are revised once there is more demand for work under MGNREGA. Over the past seven years, actual funds released to states under MGNREGA have consistently exceeded budget estimates. For example, in the fiscal year 2019-20, the budget estimate for MGNREGA was Rs.60,000 crore, but due to increased demand, it was revised to Rs.71,001 crore. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic and the sudden influx of population into rural areas led to a revised estimate of Rs.1,11,500 crore in 2020-21, compared to the original budget estimate of Rs.61,500 crore. In the fiscal year 2021-22, the budget estimate of Rs.73,000 crore was revised to Rs.98,000 crore. These figures demonstrate that the government is willing to allocate additional funds to MGNREGA in response to demand.

Source: Ministry of Rural Development

Conclusion

The Union Budget is no longer the sole platform for major policy announcements, as much more spending happens at the state level. The hype surrounding the budget is a remnant of a bygone era, and stability and predictability are essential for tax reform. The current budget is focused on empowering women, youth, and progress, leaving symbolic tax exemptions of the past behind. The Finance Minister has done an exceptional job of balancing tackling inflationary constraints and promoting economic growth. The government’s commitment to responsible financial management is commendable, even in the face of political pressure, and this budget stands as a testament to putting the country’s future first. The government has demonstrated exceptional fiscal discipline in recent years and deserves accolades for reinforcing its resolve to stick to the fiscal deficit target of 6.4%. The endeavour to simultaneously achieve rapid economic growth and social welfare improvement while maintaining responsible fiscal management is a long-term goal that requires prudent budgeting, and this budget is a step in the right direction.

Author Brief Bio: Bibek Debroy is the Chairman, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister & Aditya Sinha is Additional Private Secretary (Policy & Research), Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister.

References:

[1] Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The Political Business Cycle. The Review of Economic Studies, 42(2), 169-190.

[2] Dubois, E. (2016). Political Business Cycles 40 Years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, 166(1-2), 235-259.

[3] Rogoff, K. (1990). Equilibrium Political Budget Cycles. The American Economic Review, 80(1), 21-36.

[4] Rogoff, K., & Sibert, A. (1988). Elections and Macroeconomic Policy Cycles. The Review of Economic Studies,, 55(1), 1-16.

[5] Sen, K., & Vaidya, R. R. (1996). Political Budget Cycles in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 31(30), 2023-2027.

[6] Keynes, J. M. (1933). An Open Letter to President Roosevelt. Retrieved from University of Texas: https://bit.ly/3ScJVa2

[7] Bose, S., & Bhanumurthy, N. R. (2015). Fiscal Multipliers for India. The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 9(4), 379–401.

[8] Goyal, A., & Sharma, B. (2018). Government Expenditure in India: Composition and Multipliers. Journal of Quantitative Economics volume, 16, 47-85.

[9] Swaroop, E. (2022). Estimation of Expenditure Multiplier for India. Retrieved from IES: https://bit.ly/3YSly44

[10] RBI. (2023). State Finances: A Study of Budgets of 2022-23. Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India.

[11] Justice K S Puttaswamy (Retd.) and Another versus Union of India and others, 494 of 2012 (Supreme Court of India September 26, 2018). https://bit.ly/3XNTsph

[12] Ministry of Rural Development. (2023, February 3). Clarifications of Union Rural Development Ministry on budget cut to MGNREGA. Retrieved from Press Information Bureau: https://bit.ly/3SdCmzP