The 6th Indian Ocean Conference – IOC 2023 was hosted by India Foundation in association with the Ministry of External Affairs of India ; Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh and S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies of Singapore on May 12-13, 2023 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The theme for this edition of the conference was “Peace, Prosperity, Partnership for a Resilient Future”.

Over a span of 2 days, the Conference was addressed by a President, a Vice President, a Prime Minister, 13 Ministers, 2 Foreign Secretaries and Heads of 3 multilateral organisations. Continuing with its efforts of bringing together diverse voices under a common roof, the conference was attended by over 300 social and corporate leaders, policy practitioners, scholars, professionals and media personnel from over 40 countries.

Day 1 of the Conference on May 12, 2023 started with focusses discussions across four thematic sessions addressed by subject experts and practitioners.

Thematic Session 1

The first thematic session of the day brought together a panel of Amb Aly Houssam El-Din El-Hefny, Secretary General, Egyptian Council for Foreign Affairs, Egypt ; Ms Lujaina Mohsin Haider Darwish, Chairperson for Infrastructure Technology, Industrial and Consumer Solutions (ITICS), Oman; Shri Prasad Kariyawasam, Former Foreign Secretary, Sri Lanka and Mr Farooq Hassan, President, BGMEA, Bangladesh. The session was chaired by Shri Shaurya Doval, Member, Governing Council, India Foundation. Discussions at the first thematic session were focussed on charting a Roadmap for an economically sustainable future in the Indo-Pacific.

Thematic Session 2

The second thematic session of the day focussed on the theme “Forging partnerships in the Indo-Pacific for peace and prosperity”. It was chaired by Amb Tariq Karim, Former Ambassador, Bangladesh and had H.E. Ahmed Ali Dahir, Ambassador of Somalia to India, Somalia; Dr. Mehmet Seyfettin EROL, President, ANKASAM, Turkey; Shri Nitin Gokhale, Founder, Bharatshakti, India and Dr. Muhammadzoda Parviz Abdurahmon, Deputy Director, Center for Strategic Research under The President of The Republic of Tajikistan.

Thematic Session 3

The third thematic session of the day moved the discussions from strategy and economy to deliberating on the future of Indo-Pacific. The conversation focussed on the theme of “Rise of a peaceful Indo-Pacific for a resilient global future” and was steered by Amb Pankaj Saran, Former Deputy National Security Advisor, India.

The panel comprised of Mr David Brewster, Senior Research Fellow, National Security College, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University, Australia; Mr Sinderpal Singh, Senior Fellow, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Singapore; Mr Hossein Ebrahim Khani, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Political and International Studies, Iran and Mr Shamsher Mobin Choudhary, Former Foreign Secretary, Bangladesh.

Thematic Session 4

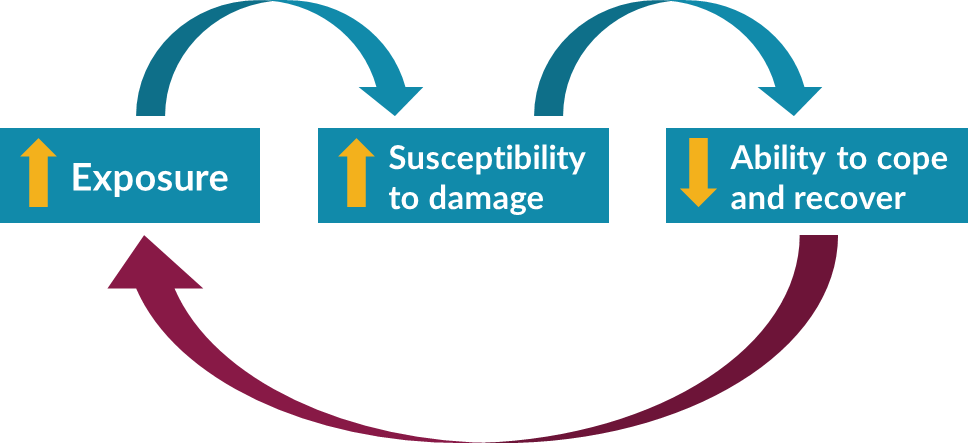

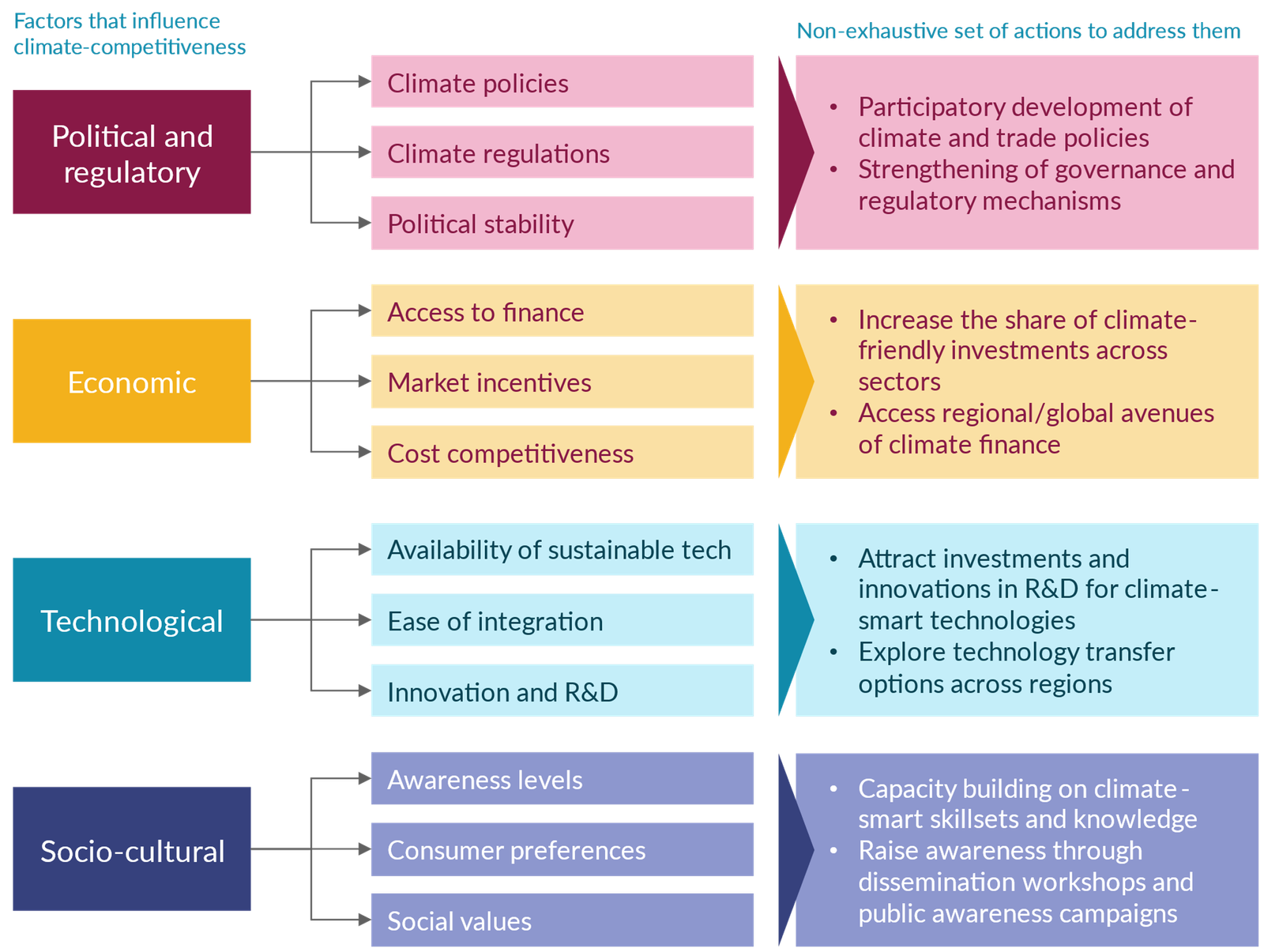

The final thematic session of IOC 2023 brought together a panel to converge diverse views on “Dealing with non-traditional security challenges for a peaceful and sustainable Indo-Pacific”. The session was chaired by Amb Vijay Thakur Singh, Director General, Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), India and was addressed by H.E J S Ndebele, High Commissioner of South Africa to India, South Africa; Dr Alexey Kupriyanov, Head, Center for the Indo-Pacific Region, IMEMO, Russia; Mr Jagjeet Sareen, Principal and Co-lead, Global Climate Practice, Dalberg Advisors, India and Ms Waseqa Ayesha Khan, Member of Parliament, Bangladesh.

Inaugural Session

The Inaugural Session of the 6th Indian Ocean Conference started with the Curtain Raiser Address by Dr Ram Madhav, President, India Foundation. In his address, Dr Madhav spoke of the geo-economic, and geo-political importance of the region. He spoke of the cultural and civilizational history that connects the region from Indonesia to Iran and from East Africa to ASEAN thus also highlighting the distinct character, identity and challenges that the region possesses.

Speaking about the evolution of the Conference since its inception its 2016, Dr Madhav elaborated on IOC not being an exclusive alliance but a forum led by Foreign Ministers of India, Singapore, Bangladesh and Oman. He called this as an “Indian Ocean Parliament” where stakeholders from different countries come together to make this a free, prosperous and peaceful region.

Delivering the welcome address of the evening H.E Dr A K Abdul Momen, Foreign Minister of Bangladesh spoke about the Indian Ocean Conference being of immense significance in bringing all equal partner stakeholders with mutual interests on a common platform to collaborate and exchange ideas with collective concerns in the field of governance. Speaking about the theme of the conference, Dr Momen expressed his optimism on deliberations over the two days being able to address the challenges being faced by the region. He expressed his gratitude to Bangabandhu, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman for his acumen and prudence for highlighting the significance of Bay of Bengal right after Bangladesh’s independence and also initiated negotiations on issues of maritime boundaries and delimitation, exploring and exploiting marine resources sustainably to promote socio- economic growth of his people. He spoke about the importance of the Indian Ocean being a crucial source of trade and transport, ocean based industries, fisheries and shipping and that the value of maritime trade has tripled over the last 15 years. He said that the various challenges the Indian Ocean Region faces due to its geo-strategic location and geo-morphological conditions require fostering partnerships and unity to maintain peace and prosperity in the region.

The Keynote address at the conference was given by Hon. External Affairs Minister of India, Dr. S. Jaishankar. In his address, Dr Jaishankar spoke of ‘Indo Pacific being a reality’ and that it has become ‘a statement of our contemporary globalization and an underlining that we are getting past the framework of 1945.’ He referred to the 4 Guiding Principles and 15 Objectives of Bangladesh’s outlook and its respect for the 1982 UN Convention on the Laws of Seas (UNCLOS) and appreciated Bangladesh’s views for its contribution for the growth and development of the region.

He spoke about the significance of the Indian Ocean nations having distinct issues arising from colonial experiences and geo-political relationships and their presence in the larger domain of Indo-Pacific and called for a more focussed approach towards these nations’ challenges. He further spoke about the importance of connectivity and re-building linkages in the post colonial era and talked about the efficient and effective connectivity with ASEAN.

Concluding his remarks for the evening, Dr Jaishankar appreciated organisations such as Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) which are working with specific mandate towards well being of Indian Ocean.

H.E Faisal Naseem, Vice President of Maldives delivered a special address at the IOC 2023. Speaking on the relevance of the theme of the conference Vice President Naseem called for unified and collective efforts to promote proactive measures involving adaptive management and innovation in leadership for a resilient and sustainable future and managing uncertainties and risks to ensure peace in the region. He spoke about the Indian Ocean Region being home to the fastest growing civilizations and a hub for trade with the Middle East, Africa, East Asia, Europe and America and that the responsibility to ensure peace, economic prosperity, environment protection and international rules in the region is a collaborative effort of all the countries.

He highlighted the current major concerns of the Indian Ocean, that is, the exploitation of marine resources, climate change and the vulnerable conditions of most of the population residing in the low lying coastal settlements of the region. He spoke about living in a more interconnected society and evolving as a unified community in the post-pandemic world as the pandemic revealed numerous economic vulnerabilities in the global supply chain and starkly reminded us the importance of building harmonious relations to guarantee an undisrupted supply chain. Concluding his address, the Hon’ble Vice President called for enhanced cooperation in upholding the spirit of partnership, inclusiveness, openness and intensive dialogue to ensure a prosperous future for the Indian Ocean Region.

H.E. Prithvirajsing ROOPUN G.C.S.K., Hon’ble President of Mauritius delivered the Inaugural Address of the 6th Indian Ocean Conference 2023. In his remarks, he paid tribute to the Father of the Nation of Bangladesh, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Expressing the complete endorsement of Mauritius for the theme of 6th IOC 2023, he appreciated its positive underpinnings and futuristic orientation. He went on to describe the pivotal role of initiatives taken up by Mauritius, such as the Indian Ocean Commission, which has extensively worked on critical issues such as preservation of ecosystems, sustainable management of national resources, renewable energy and maritime safety.

In his concluding note, he stated that, “We should strive to maintain a peaceful environment within the Indian Ocean region and beyond. Peace is essential, without peace there is no prosperity. But prosperity also demands that we look beyond our diverse national ambitions. No country, big or small, has the ability to build a resilient future on its own. Thus, we should all partner. We need collective actions among regional organizations, governments, the private sector, and civil society.”

Delivering the Chief Guest of the conference, H.E. Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh spoke about the economic and strategic significance of the Indian Ocean Region along with the challenges it faces and thus, the need to foster partnerships and cooperation for ensuring peace and prosperity for all. She spoke about Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman enacting the ‘Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones Act, 1974’ to set the limit of Bangladesh’s ‘Maritime Zones’ and facilitate exploration of sea resources and this particular act coming into force eight years prior to ‘United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982’.

She elaborated on Bangladesh’s views on ‘Culture of Peace’ as an essential element that would reinforce all aspects of peace and that Bangladesh is committed to UN’s global peacekeeping and peace-building endeavors. She said that Bangladesh has been a hub of maritime activities and has been active in many regional arenas and also Bangladesh is the current Chair of the Indian Ocean Rim Association and the current President of the Council of the International Seabed Authority.

She underlined six priority areas of engagement; firstly, countries in the Indian Ocean Region should foster ‘Maritime Diplomacy’; secondly, enhanced cooperation to reduce the impact of natural disasters; thirdly, strengthening mutual trust and respect to build stronger partnerships to ensure stability for a resilient future; fourthly, strengthening existing mechanisms on maritime safety and security in the Indian Ocean and upholding exercise of freedom of navigation in accordance with international law; fifthly, promoting ‘Culture of Peace’ and focusing on people centric development; sixthly, promoting transparent and rules-based multilateral systems that would facilitate equitable and sustainable development in the region and beyond through inclusive growth.

Day 2 – May 13, 2023

Plenary Session 1

The first plenary session of day 2 was hosted by Shri Suresh Prabhu, Chairman, Governing Council, India Foundation; Former Union Minister, Government of India. The panel for the session included, Hon. Dr Maliki Osman, Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office and Second Minister of Foreign Affairs, Singapore; Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Ports, Shipping and Aviation, Sri Lanka and Hon. Josoa Rakotoarijaona, Minister of National Defence, Madagascar.

Shri Suresh Prabu started the session by highlighting how at a time when the world may seem fragmented to some, ministers from various countries across the world are coming together to discuss a strategy for unity and cooperation. He said, “At such times, when everything is getting fragmented, we are meeting here to actually ascertain what we can do together to make, through us, our societies feel secure, better and over a time more prosperous”.

Hon. Maliki Osman highlighted the importance of the Indian Ocean region from an economic, trade and environmental perspective. He spoke on the importance of upholding multilateral trading systems and resisting protectionist policies by emphasising on how these very multilateral trading systems are playing a key role in the recovery of economies of various countries post covid and provided opportunities to explore new avenues for economies to receive a much required boost and relief post pandemic and lockdowns.

He said that, “We saw how international connectivity is a double edged sword, while it enhances international trade, it can also disable trade links. However, the crisis (COVID 19) also provided an opportunity for countries to work together in both traditional and non-traditional areas, relook existing institutions and regional mechanisms and revamp them in order to better serve today’s needs.” The minister also urged countries in the Indian Ocean Region to work together to support the full implementation of the Paris Agreement and strengthen collective resilience against rising sea levels which is increasingly becoming a major concern for all the countries in the region.

Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva took to the stage providing the Sri Lankan perspective on peace, prosperity and partnership in the Indian Ocean. He said that countries of the region have historically played a significant role in global trade and commerce and even today, the region remains a lifeline for global trade. He said, “In the emerging multipolar world, where Asia has become a major economic power, Managing competition and strengthening cooperation is essential to the peaceful development of the region” He emphasised that it is time for the Indian Ocean Countries to take a role in determining their own future and ensure that the Indian Ocean sustains its status as a peaceful and prosperous region where all nations can equitably benefit from its abundant resources in a sustainable manner.

Hon. Josoa Rakotoarijaona in his address elaborated on Madagascar’s vision for the development of the region and the role played by island nations. He spoke of the need to ensure mechanisms to address maritime zone violations as well as to establish a functional and effective framework to manage natural disasters such as hurricanes, cyclones and their often overarching cause i.e., global warming. He said, “We have 13 goals instored by the Madagascar President and Peace and security is the very first goal and it is also the priority of our country”.

Plenary session 2

The second plenary session of the day was chaired by Mr. M J Akbar, Member, Governing Council, India Foundation and Former Minister, Government of India. The panel comprised of Hon. Charles E. Fonseka, Minister of the Interior, Seychelles; Hon. Tandi Dorji, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bhutan; Hon. Narayan Prakash Saud, Foreign Minister, Nepal; Hon. Sayyid Badr bin Hamad bin Hamood Albusaidi, Foreign Minister, Oman; and Hon. Wendy Sherman, Deputy Secretary of State, United States of America.

Addressing the panel, Hon. Charles E. Fonseka, Minister of the Interior, Seychelles termed the Indian Ocean Region to be a “beacon of hope” for a strong collective towards peace and stability. He also spoke of the the challenges and instability that plague the region int he form of the insidious trafficking of narcotics and illicit drugs trading. The implications of such calamities impact the security, stability and well being of the entire region and affect the workforce and economic balance of the country.

Apart from nefarious drug trade, the minister also spoke about illegal and unregulated fishing casting a shadow over sustainable management of marine resources and the livelihood of coastal communities, in regard of which he acknowledged the pivotal role played by existing regions and international frameworks and agreements on fisheries management such as IOTC (Indian Ocean Tuna Commission) and PSMA (Port States Measures Agreement). He spoke of Seychelles’ unwavering determination for collective security and bolstering of joint patrol with regional partners in the maritime domain avoiding criminal activities and strengthening the pillars of law enforcement and judicial awareness. He concluded by highlighting the importance of the need for future cooperation and for strong and unwavering support to enhance cooperation among the countries by enhancing dialogue.

Hon. Tandi Dorji, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bhutan spoke about the infinite potential of the Indian Ocean region for establishing peace and prosperity in the region along with the challenges the region faces for ensuring the same. Speaking about the Indian Ocean region being home to some of the world’s busiest shipping lanes and critical for world trade and commerce and consisting of rich diversity and culture, he said that the region is also vulnerable to “traditional challenges of security, emerging threats of bio hazards, cyber warfare and maritime piracy” endangering the economic interests, security and well being of people.

He asked for a collective efforts to tackle these challenges by “leveraging our collective strength and resources to build a more secure and peaceful region based on principles of rules based order” and stated that Bhutan actively contributes to the peace building of the region. Speaking about prosperity of the region, he stated that the Indian Ocean region has “economies of scale, immense consumer market and the technical prowess which can propel the world into an era of global affluence based on the ethos of sustainable development.” He called for collective efforts of the countries to reach for an inclusive growth and brighter future for the people of the region. He also recognized the endeavors of India and Bangladesh for taking climate conscious decisions while implementing developmental imperatives. With regard to partnerships, the minister asked to collectively recognize the challenges of climate change, natural disaster and pandemics and to work towards building resilience and preparing for the future in respect of which Bhutan has taken steps to remain carbon neutral and promote sustainable tourism. He stated that “the Indian Ocean region is no longer based on the arithmetic of contemporary power equations but a natural construct based on the principles of inclusivity, camaraderie and multi stakeholderism.”

Hon. Narayan Prakash Saud, Foreign Minister, Nepal pointed out the economic and strategic significance of the Indian Ocean region and its importance as a gateway for international markets for landlocked countries like Nepal. He also spoke about the countries in the Indian Ocean Region working together on the grounds of mutual respect and justice for all nations. He talked about the climate crisis that has endangered the coastal and hinterland states and asked about true international commitment to accelerate the green energy solutions and more actions on ground towards climate change. He shared the commitment of Nepal towards achieving the goal of Net Zero Emissions by 2045 and also working in the field of hydropower energy for clean energy solutions. He said that the interconnectedness among the countries of the Indian Ocean region must go beyond the reason of economic and strategic importance and work towards sustainable and maritime well being and look out for more transformative actions against pollution and chemicals. He called out for assistance for landlocked countries to overcome their geographical constraints through better collaborative partnerships, conclusiveness and cooperation and that Nepal is committed towards engaging constructively and responsibly for a peaceful and resilient future.

Addressing the conference virtually, Hon. Sayyid Badr bin Hamad bin Hamood Albusaidi, Foreign Minister, Oman spoke about the strategic significance of the Indian Ocean region which serves as a “vital link connecting the East with the West” and also a “gateway for cultural exchange and intercontinental cooperation.” The minister stated the significance of Oman’s “quiet diplomacy” and stable and balanced relations of mutual respect with the neighboring countries. He also spoke about the importance of dialogue as the best chance of peace. He spoke about the significance of maritime security and collaborations enabling peaceful trade and investments. He also spoke about Oman’s Vision 2040 development plan which aims particularly for port development which would substantially reduce overall transit times and costs and called for regional and international cooperation in the Indian Ocean Region economic prosperity and sustainable development and through Oman’s three major ports, Salalah, Sohar, and Duqm which would boost regional trade and connectivity. In his concluding remarks, he talked about promoting peaceful partnerships and strengthening cooperation in the international arena with cohesiveness and transparency.

The last address of the session was given by Ms Wendy Sherman, Deputy Secretary of State, United States of America. She stated that the United States is “committed to elevating its engagement in the Indian Ocean region.” She also spoke about the serious challenges of the climate crisis, piracy and armed robbery at sea, trafficking and illegal and unregulated fishing that is degrading the blue economies across the Indian Ocean region and that these challenges require concerted and collaborative efforts. She said that the United States is working towards providing developmental assistance focused on the growth of sustainable blue economies.

Plenary Session 3

The third plenary session was chaired by Hon. Md Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh. The panel comprised of Hon. Tim Watts, Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs, Australia; Hon. Do Hung Viet, Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, Vietnam; Hon. Takagi Kei, Parliamentary Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan; Hon. Saeed Mubarak Al Hajeri, Assistant Minister for Economic and Trade Affairs, United Arab Emirates (UAE); Hon. Dr. Soeung Rathchavy, Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Cambodia; and Hon. Seyed Rasoul Mousavi, Advisor for Minister of Foreign Affairs, Iran.

In his introductory remarks, Hon. Tim Watts, Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs, Australia, noted that Australia’s prosperity and security were intimately tied to the Indian Ocean. He stated, “The Indian Ocean’s shipping lines are crucial to the energy security and to the economies of many countries around the world including our own, and global trade depends on stability and security here, particularly the security of crucial checkpoints that are so fundamental to an open, stable and prosperous region. And looking beyond trade, the Indian Ocean is also one of the key points of confluence for global strategic competition today. In an age in which we rightly obsess about the health of our global environment, the Indian Ocean is an area where the impacts of global warming and other environmental challenges will be felt the most. Hence, the salience of the theme of this year’s conference.”

He elaborated on Australia’s deep commitment to the betterment of the region “We recognize the urgency of the issues that we face right across the region, not least, climate change and health of global oceans. Turning inwards is not the answer. The answer is the very opposite. It is redoubling our efforts to work together in an open, collaborative and sustainable way through regional and global institutions and systems that promote cooperation through a strong, supported, multilateral, rules-based system, through open, non-distorting markets even as we work together to decarbonise our economies, through science and evidence-based decision making. Australia commits to this work, Australia would play its part, and a measure of our commitment working together and to the Indo-Pacific is that Australia is honored to be able to host the next iteration of this conference in 2024.”

Hon. Do Hung Viet, Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, Vietnam, touched upon the various traditional and non-traditional security challenges posed across the globe, further fuelled by increasing tensions between various countries, he discussed the potential future of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) as the “most populous, most prosperous and most developed region” in the coming decades. The geostrategic, geoeconomic and geopolitical significance of the “Indo-Asia-Pacific centric” region could lead to situations of conflict if not managed beforehand. Sharing his thoughts on the crucial steps required to achieve a peaceful, prosperous and resilient IOR, he emphasized on the need to build “an open and inclusive regional architecture that adheres to the fundamental principles of international law”, with ASEAN playing a central role in facilitating dialogue and cooperation in the region.

Hon. Takagi Kei, Parliamentary Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan

In her address, Hon. Dr. Soeung Rathchavy, Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Cambodia laid out Cambodia’s commitment to the IOR. She highlighted ensuring peace for the overall development of the IOR as Cambodia’s top priority. Advocating a ‘spirit of openness’ for the region, she noted that the reduction of trade barriers and promotion of international trade, particularly with respect to crucial commodities like food and energy, would help in enhancing the “resilience of regional and global chains”.

She stated, “We should devote special attention to strengthening cooperation and promote robust partnerships in the areas of capacity building, capacity development, acceleration of digital transformation and development of the digital economy, which is a new source of growth for the least developed countries. In this context, as digital technology has been rapidly advanced and has become a catalyst for economic growth, the Royal Government of Cambodia focuses on the effective implementation of the Cambodia digital economy and society policy framework 2021-2035, and also Cambodia Digital Government Policy 2022-2035, and other related policies.”

Hon. Seyed Rasoul Mousavi, Advisor for Minister of Foreign Affairs, Iranbegan his remarks by noting the shifting paradigms of theories about international relations and politics. He stated that there has been a shift from focus on globalization to intellectual deliberations on regionalization, along with the change “from unipolarity to multilateralism” and an “increasing importance of geography, geopolitics and geoeconomics”. This would imply a rise in the need for regional cooperation amongst countries. In his speech, he emphasized the need for thinking about new gateways to the Indian Ocean region which could facilitate crucial junctions for global trade. In this regard, he noted that the Iranian port of Chabahar is emerging as a central gateway to the Indian ocean as it connects the IOR countries to Eurasia, Central Asia, Caucasus and the Black Sea.

Session 4

The fourth session was hosted by Hon. Saurabh Kumar, Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India. The panel consisted of, Hon. Ahmed Latheef, Foreign Secretary, Maldives; Hon. Tenzin Lekhpell, Secretary General, BIMSTEC; Hon. Esala Weerakoon, Secretary General, SAARC; Hon. Isiaka Abdulqadir Imam, Secretary General, D8; Hon. Paul Vincent Uy, Assistant Secretary, Department of Foreign Affairs, Philippines and Hon. Afreen Akhter, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, USA.

Hon. Tenzin Lekhpell spoke of the significance of BIMSTEC as a bridge between South and South-East Asia. He noted that the evolving central role of BISTEC requires commitment, creativity, innovation, sustained political will, openness and vision among the BIMSTEC member states. He said, “I believe that all of us at this conference, representing different member states and organisations, are here because of our commitment to have a shared vision of the Indian Ocean built on peace, security, stability and prosperity. As a state led and government driven organisation the BIMSTEC member states set the agenda for BIMSTEC and I hope that the BIMSTEC member states will ensure that BIMSTEC evolves and grows in a manner in which it can play a central role in achieving this shared vision.

Hon. Isiaka Abdulqadir Imam highlighted the fact that the D8 is a unique organisation with member states across 3 continents: Asia, Africa and Europe and 5 member nations, namely, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia and Pakistan in the Indian Ocean Region. He said, “One key element through which D8 has contributed to creating peace and prosperity among it’s member states and in the Indian ocean region is through collaboration or partnership”. He further emphasised the importance of cooperation for stability such that a business friendly environment can be created across the region.

Hon. Paul Vincent Uy elaborated on Phillippines’ approach towards the Indian Ocean Region with a primary focus on ASEAN centrality in the Indo-Pacific. He said, “Philippines joins the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific or AOIP and recognizes ASEAN centrality which is the main principle that promotes cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region.” He emphasised on the importance of countries to adhere to established international maritime laws and follow a peaceful path of resolution.

Hon. Esala Weerakoon spoke of the fact that members of the SAARC are also stakeholders in the Indian Ocean Region. He said, “Peace, progress and prosperity remain the key components of sustainable socio-economic development in today’s interconnected and interdependent global order” He emphasised the importance of preserving the ecological balance of the region, the mountains, the low lying lands and the ocean.

Hon. Afreen Akhter highlighted efforts by the United States to help the countries of the region to deal with the negative impacts of climate change. She also discussed the role of the US in pushing investment into the region. She said, “Geopolitics does not drive our relationship with the region. We work bilaterally and multilaterally in order to bring security, prosperity and collective unity in this region. So we are very focused on the Indian Ocean Region as I outlined. We have a number of Investments and we are really looking to build our partnerships where those partnerships make sense.”

Summing up the proceedings of the conference over two days, Amb Kumar spoke of the important role being played by regional and multilateral bodies in shaping the global agenda of the future. He spoke of the role being played by such organisations in ensuring peace, prosperity and partnership in not just the region but the world while commending their leadership for building global institutions with such commitments.