Removing State Control from Religious Institutions: Constitution (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (Amendment of Article 26)

Legality of Collegium and the NJAC Debate

Constitutionality of the Re-organisation of Jammu and Kashmir

Challenges of Indian Aviation MRO Industry

India Foundation Journal January February 2020

Focus: Theme: The Constitution of India : Contemporary Issues?

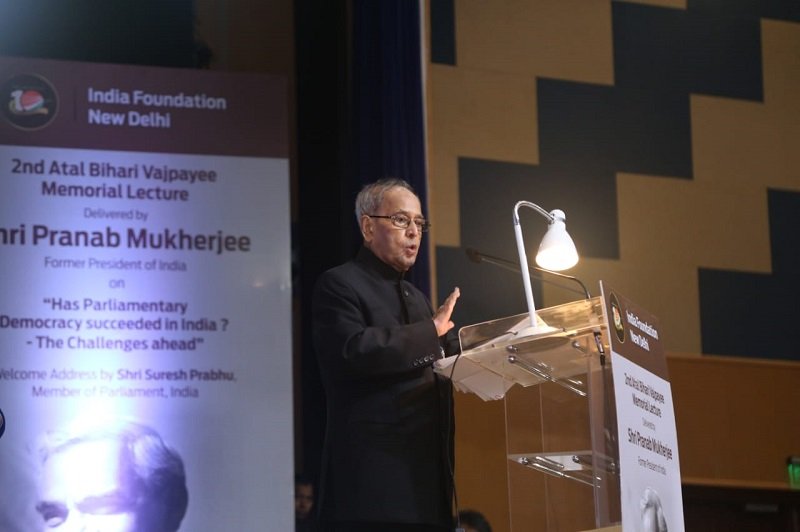

2nd Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture

India Foundation instituted the India Foundation instituted the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture in 2018 to celebrate the legacy of the Former Prime Minister of India Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Shri Vajpayee personified the spirit of nationalism, integrity in public life and approach towards politics.

The First Lecture was delivered by Former Finance Minister of India Shri Arun Jaitley in Delhi on the theme of “Indian Democracy: Maturity and Challenges” at the 4th India Ideas Conclave in 2018.

The Second Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture was delivered by the Former President of India Shri Pranab Mukherjee on December 16, 2019 in New Delhi, India. The theme of the second lecture was “Has Parliamentary Democracy Succeeded in India and the Challenges Ahead”.

Former President Mukherjee spoke of his admiration for Atal Ji for his innate qualities of being an orator, moderator and consensus seeker. Speaking of the evolution of parliamentary system in India, Shri Mukherjee spoke of three phases of British influence phase of post independence India; multi-party coalition stage of 1990s and the third phase where the multi-party system slowly started changing to a bipolar system where in two major coalition blocks came to dominate Indian polity after the elections of 1998. He, however, went on to commended the fine balance between electoral majority and majoritarianism that the parliamentary system in India has achieved.

He concluded by highlighting the shortcomings of the system and expressing hope that that Parliament of India will live up to the task of ensuring that Indian democracy provides for an enabling environment which helps every section of the society to fully participate in the process of governance.

The Address was attended by over 300 eminent citizens from all walks of life. The audience comprised of Ministers, Member of Parliaments, Bureaucrats, Political Leaders, Diplomats, Media Personalities, Corporate Leaders, Academics and Scholars.

If not Democracy, then what?

Anti-CAA demonstrations took a violent turn in some Muslim dominated districts of the country. Rowdy crowds have inflicted huge damages on public property. This raises an important question. Have the people of this country taken to the spirit of democracy during the seventy-three years of popular governance? In the course of its long stint in power since independence, the Congress has been claiming with great élan that it is making an enviable experiment of moderating Indian Muslims by using a proven tool called secular democratic dispensation as is enshrined in the Constitution. The objective has been to help the Muslim community integrate into the national mainstream. In other words, Congress meant to assert that Islam and democracy/secular democracy, seemingly a contradiction in terms, are reconcilable. The intentions were unassailable, and as a matter of simple logic, if any segment of Indian Muslims doubts or contradicts the paradigm, the logic will not be on their side.

Nevertheless, the sudden outburst, first at three or four universities in the country, with the Muslim tag appended to them notionally or virtually, and then the escalation of violence and vandalism in almost all important Muslim dominated pockets in various states of the country, ruthlessly demolished the edifice of de-radicalising of Indian Muslim community which the Congress claims it assiduously built over decades by adopting pro-Muslim pacifist and even solicitous policies at different levels. Many a time, the national mainstream expressed unease at this overdone conciliatory stance. Nevertheless, standing by its characteristic quality of tolerance, the masses of Indian people did not make an issue out of the ongoing large scale vandalising that could have the potential of disrupting and endangering civilian life and property.

The misfortune of the Congress is that after its grand old titans phased away, and the second and third rung leadership donned the mantle, it gradually dawned upon them that they were far behind their pioneers in popularity and public response. The generation gap was wide enough and would not let them cash on the big names for all times. Therefore, a new mechanism of retaining political ascendency had to be created. Simultaneously, they were confronted with the emergence of a new socio-political phenomenon called the culture of identity in the Indian civil society. It posed a serious challenge to the popularity and status of the traditional Congress party. After all, the impact of the steady growth of the Indian economy could not be underestimated. The rise of the culture of identity was a glaring manifestation of that impact. The task of the Congress to maintain its supremacy was becoming more and more arduous.

Unfortunately, the Congress, looking out for political crutches, committed the grave blunder of shifting its ideological goalpost from passionate and universal nationalism to the narrow confines of the national minority of Indian Muslims. In doing so, it first deliberately built the “oppressed, discriminated and deprived” profile of the Indian Muslim community, and then, on that premise, began to legitimise its policy of appeasement and pusillanimity towards the Muslim community. This was the beginning of an ugly and disastrous phase of Indian democracy, namely the vote bank politics. In carrying forward this policy, Congress, out of sheer lust for power, created an icon (Indian nationalism) to whose doorsteps it would bring all imaginable blames.

They branded the Indian nationalists variously like “tyrannical majority,” “Hindu terrorism” and even “Nazi dictatorship”. With that, the Congress party claimed that only they could provide security and prosperity to the Muslims of India while the rest of them, particularly the nationalists, were their detractors. Had Congress confined itself to the economic and social uplift of the Muslims of India and not created a political concoction, it would have immensely contributed to the integration of the Muslims into the national mainstream. The street rages and vandalism that we see today in Muslim dominated sectors in the entire country is what the Congress and its close associate the Left, nurtured for so many decades. They sadistically sowed the wind and the Indian nation must now reap the whirlwind.

If the Muslims of India have remained outside the national mainstream, the cause is firstly the wrong approach of Congress and secondly the absence of right-thinking leadership among the Indian Muslims. By succumbing to the egotistic socio-political philosophy of the Congress, the Muslims of India not only sidelined themselves from the national mainstream but also unwittingly created a wedge between them and the national majority. The widespread protestation by a section of the Indian Muslims that has emerged in the aftermath of CAA is part of the political game of Congress and its dissenting allies to create disorder in the country. It will be noted that Congress has resorted to these tactics after it exhausted all other options of derailing the elected government at the Centre.

It is for the first time since independence that some Indian Muslims have come out openly and violently against the elected government in the country and against the sovereignty of the Indian Parliament. Interestingly, the anti-India and anti-Indian majority campaign is being waged while brandishing the Indian tricolour, unlike the Kashmiris who generally brandish either the black or the Pakistani/ISIS flags in their anti-India demonstrations. Waging violent demonstrations under the shadow of Indian tricolour is certainly a method in the madness called takkiya in Islamic terminology.

By these exclusivist protest rallies, this section of Indian Muslims have indicated that they reject the Indian secular democratic dispensation as did the founders of Pakistan seven decades ago. The question is: If this section of Indian Muslims do not want a democratic dispensation, what do they want then? Do they want to force the Indian nation to ask for a declaration of India as a Hindu state like Pakistan? We have a word of admiration for the Modi government which did not lose its cool during the ongoing scenes of vandalism, arson, loot and violence in the country. This is how the government of the world’s largest democracy should behave. The Hindu community leaders equally deserve appreciation for not allowing the masses of people to go mad after a handful of miscreants. How regrettable that the chief of the Congress has publicly announced her party’s support to the students but has not said a word of warning or advising them to desist from vandalism, and respect the law of the land. She clings to the vote bank, and surprisingly she learnt nothing from her son having to run away from his traditional constituency in UP to a predominantly Muslim dominated constituency in Kerala. It appears that Ms Gandhi needs to support the elements in or out of the country that aspires and work for disintegration of India.

The widespread protestation by the Indian Muslims is not just a local affair. We are aware of various inimical forces on the international plane working towards the breaking of the Indian Union. After having played and exhausted its role in the Middle East, the rabid Islamic jihadists and suicide squads have shifted the scene of the contemporary war of civilisations from the Middle East to India. The concentration of all terrorist jihadists and suicide bombers of Pakistan along the Indo-Pak border, Pakistan’s repeated threats of using weapons of mass destruction, China’s dangerous posture in the Indo-Pacific oceanic region, outright anti-India stance of Turkey, Egypt and Malaysia, and the vast scale propaganda and disinformation unleashed by sections of biased national and international media, all point toward a global conspiracy purporting to destabilise the elected government in New Delhi and disintegrate the Union of India just because Indian Prime Minister is fighting Islamic terror at many world forums. Many countries are enviously looking at India’s growing economic and scientific power as a challenge to their status in the international arena. Many anti-national elements within the country or the Urban Naxals are accomplices in these perfidious acts. It is a shame for the opposition, one and all, that at a time when our enemies on the west and the east have forged an unholy alliance and are poised to strike at India in various ways, the opposition is contributing to its own disaster.

It must be noted that the protestation methodology adopted by anti-CAA crowds country-wide, is precisely the replication of the methodology adopted by the Kashmiri militants, dissidents and secessionists viz. stone-throwing and attacks on the police, torching public property and public and private vehicles, using black masks to avoid identification, contriving media, males disguising as females, raising slogans of ‘Azadi’ and responding to police authorities by saying that their respective localities are peace-loving but miscreants come from other localities etc. The only difference is that while the Kashmiris raised Pakistani or ISIS flags, the Indian Muslim crowds raised the tricolor only to be humiliated rather than respected.

This perfidy has to be uprooted. History has shown that the Indian nation has the inherent strength to survive through cataclysms and catastrophes. Today, the nation is in the hands of an honest, able and bold leadership, led by a man of the masses. Indian Sanskriti, disowned and then despised and reviled by the invaders is reborn and will thrive in full glory. This Sanskriti is the common heritage of all those who call themselves Indians. That is why, it behoves the Muslims of the country not be misled by a few disgruntled elements amongst them who preach vitriolic hate and strive to weaken the nation through a divisive ideology and through vandalism. These elements are doing great harm to the Muslim community, which needs to stand up and reject their hate-filled ideology. It is time for all Indians to rise as one and build the foundations of a strong country.

*The writer is the former Director of the Centre of Central Asian Studies, Kashmir University

Roundtable discussion on India-Vietnam Relations

Wordpress is loading infos from thehindu

Please wait for API server guteurls.de to collect data fromwww.thehindu.com/news/national/...

India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue by India Foundation

Special Address by Hon’ble Tony Abbott, Former Prime Minister of Australia, on “Vision for a Free & Open Indo-Pacific Date: 18 November 2019

Conference on India-Myanmar Relations on theme “Connecting India’s Northeast with North West Region of Myanmar: Roadmap for all round prosperity”.

Round-table Discussion on “The Chennai Spirit: India-China Relations”

Report of the Ninth Round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue

November 1-2, 2019

Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh

Configuring The Bangladesh-India Strategic Space

Inaugural Session

Building on the strong foundations of India-Bangladesh bilateral ties, the ninth round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue commenced on November 1, 2019 at Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. This round was organized by India Foundation and Bangladesh Foundation for Regional Studies. It was supported by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh and Friends of Bangladesh. The event commenced with a pre-conference interaction to highlight the goals and achievements of the Dialogue. This interaction was led by Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh and Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation.

The inaugural session was graced by the presence of Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury, Hon’ble Speaker, Bangladesh Parliament; Mr. Ram Madhav Varanasi, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party & Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation; Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh; Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma, Hon’ble Minister for Finance, Transformation and Development, Health and Family Welfare, PWD, Government of Assam, India; Mr. MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India; Ms. Riva Ganguly Das, High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh; Mr. M. Shahidul Islam, Secretary General, BIMSTEC; Md. Shahidul Haque, Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh; Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami, Director Techno International College of Technology and Working President, Friends of Bangladesh (India Chapter); and Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation. The inaugural ceremony also witnessed the presence of several other esteemed and learned dignitaries from Bangladesh, along with the delegation from India.

Mr. MJ Akbar credited the last five dialogues with achieving more success in bringing the two nations closer as compared to the relations between the two in the last 20-25 years. Md. Shahriar Alam highlighted the multifaceted relationship between the two countries rooted in the shared history and geographical proximity. He underscored the civilizational, cultural and socio-economic links and consequently, the commonalities between the two. Listing new areas of cooperation, Hon’ble minister regarded it as an example of maturing India- Bangladesh relationship.

Mr. M. Shahidul Islam focused on his strong belief that a sound relation between India-Bangladesh is conducive to the peace, progress and prosperity of the entire BIMSTEC region. He said that in an increasingly interdependent world, the cherished ideals of peace, freedom and economic well being are best attained by fostering greater understanding, good neighbourliness and meaningful cooperation among the countries of the same sub-region already bound by ties of history and culture.

Ms. Riva Ganguly Das while highlighting the various nuances of India-Bangladesh relations, focused on the trajectory followed by India in becoming the net employment generator in Bangladesh, while also indulging in capacity development. She brought into discussion the various projects undertaken that will forge stronger connectivity ties between Bangladesh and the North-Eastern states of India.

Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma in his address appreciated the efforts of Her Excellency Sheikh Hasina’s government in fighting terrorism, which have immensely contributed to the peaceful and secure economic prosperity of Assam. Concentrating on the geographical proximity of Bangladesh with the North-Eastern states, he urged the Bangladeshi government to take proactive measures to strengthen trade and commerce in the region.

Mr. Ram Madhav Varanasi commenced his address by highlighting the commonalities between the two countries in reinstating faith in their national leaders and designing national agendas on similar themes to strengthen their respective countries, while also reinforcing the bilateral relationship. He traced the relationship between he two countries to be built on sentiments, beyond the tangible contents of several agreements signed between the governments. He highlighted that the relationship transcends the nuances of a strategic partnership and is deeply rooted in strong historical and fraternal ties based on sovereignty, equality, trust and understanding.

Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury focused on the comprehensive scope of the theme for the ninth round of the dialogue. Describing the ‘Bangladesh-India Strategic Space’ as an innovative concept of cooperation, she regarded it as a notional setup providing framework within which issues of mutual cooperation can be fitted in and taken forward in a planned and methodological manner to attain shared goals. She highlighted the need to keep working together and be responsive to the emerging challenges to ensure that the two countries can grow with shared prosperity, while also formulating innovative modes to resolve the pending issues amicably and peacefully.

The vote of thanks was delivered by Shri. Alok Bansal. This was followed by a cultural programme showcasing the rich heritage of India and Bangladesh. Thereafter, dinner was hosted by AJM Nasir Uddin, Mayor, Chattogram City Corporation.

Session I: Trade, Investment to Generate Employment

Chairperson: Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh

Keynote Speaker: Dr Atiur Rahman, Department of Development Studies, Dhaka University & Former Governor, Bangladesh Bank

Panelists:

- Kushan Mitra, Managing Editor, The Pioneer, India

- Dr Nazneen Ahmed, Senior Research Fellow, BIDS, Bangladesh

- Preeti Saran, Former Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs, India

- Tarik Hasan, Treasurer, Suchinta Foundation, Bangladesh

Md. Shahriar Alam in his initial remarks categorized poverty as the biggest enemy for both the governments and ensuring trade and investment that can generate employment as amongst the most important tools to combat it.

Dr Atiur Rahman presented the initiation paper on the theme for the session and highlighted the unprecedented level of willingness to cooperate shown by the governments. He deliberated on the need to broaden the trade infrastructure, digital and other forms of connectivity which will generate employment both directly and indirectly, while also contributing to the economic growth story of both the countries.

Mr. Kushan Mitra focused his remarks on the automotive industry and the start-up ecosystem. He stated that there is immense potential in improving the ease of doing business in both the countries and that both should learn from each others experience, while also facilitating policy suggestions and adaptation to the other.

Dr Nazneen Ahmed stressed on the strategic importance of growing young population in both the countries. She highlighted the need to facilitate in setting up not just educational institutions, but also other forms of institutional designs that can provide access to information and opportunities to enhance their employability.

Ms. Preeti Saran expressed her concerns over the unrealized potential of trade between India and Bangladesh, despite the quantum having increased by nearly three folds. Inland waterways is one such sector, the investment in which will have direct bearing on the overall trade narrative and employment opportunities.

Mr. Tarik Hasan in his remarks focused on the need to ensure competitive value for exports in both India and Bangladesh to build on the existing trade and commerce exchange. He also focused on the need to proactively engage Bangladesh with the North-Eastern part of India to tap the unrealized potential.

Session II: Connectivity

Chairperson: Himanta Biswa Sarma, Hon’ble Minister for Finance, Transformation and Development, Health and Family Welfare, PWD, Government of Assam, India

Keynote Speaker: Dr Sreeradha Dutta, Centre Head and Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Vivekananda International Foundation, India

Panelists:

- Dr Atiur Rahman, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Dr Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Regional Studies Initiative, ORF, India

- Dr Delwar Hossain, Department of International Relations, Dhaka University, Bangladesh

- Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation

Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma in his initial remarks reiterated the commitment of Shri. Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India to bring transformation by facilitating transportation. He highlighted the impact of a strong infrastructure of highway, internet, railway and airway on relations between two countries.

Dr Sreeradha Dutta initiated her address by bringing to light that connectivity begins with the convergence of ideas, thoughts, interests and values, which ultimately develops the infrastructure and transportation. She highlighted the need to work on the logistical infrastructure on both side of the border, while also ensuring a strict mechanism to deal with security threats disrupting trade.

Dr Atiur Rahman provided a different spectrum to understand the connectivity between India and Bangladesh. He focused on the important role that agriculture and horticulture can play in strengthening the cooperation in supply-chain management. He urged to improve the connectivity by making borders the access points, facilitating an easier visa regime and focusing also on educational connectivity.

Dr Joyeeta Bhattacharjee in her address spoke about the importance of connectivity through information. She focused on the need to work positively towards the changing perception about each other in the two countries, while also ensuring that connectivity is not just seen from the lens of hard infrastructure, but also through the soft lens of people, ideas and minds.

Dr Delwar Hossain emphasised on the trajectory that made connectivity a basis for strong India-Bangladesh relations. He focused on the need to add financial connectivity as a paradigm while analysing connectivity between the two countries. There is a pressing need to smoothen financial transactions across the borders and develop new modes of connectivity for shared economic prosperity and growth.

Mr. Alok Bansal in his address focused on the need to enhance connectivity to ensure that the two growing economies, India and Bangladesh can live up to their true potential, especially between the North-Eastern region of India and Bangladesh, owing to their existing geographical proximity and cultural similarities. He also emphasised on the need to shift the transport of bulk freight from road to rails in order to facilitate trade of perishable goods and consider the idea of building a tourist grid to connect the two countries.

Session III: Technology, Power and Energy

Chairperson: Muhammad Nazrul Islam, Bir Protik, former State Minister for Water Resources, Bangladesh

Keynote Speaker: Md Abdul Aziz Khan, Member, Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission

Panelists:

- Veena Sikri, Professor, Ford Foundation, Chair, Bangladesh Studies Program, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi & former High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh, India

- Major General AKM Abdur Rahman, Director General, Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies

- Guru Prakash, Assistant Professor, Patna University & Advisor, Dalit Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, India

- Tanvir Shakil Joy, former Member of Parliament & Former Convener of Climate Parliament, Bangladesh

Muhammad Nazrul Islam discussed the importance of technology, power and energy for strengthening the India-Bangladesh cooperation.

Md Abdul Aziz Khan in his initial remark attributed a significant proportion of the tremendous growth of Bangladesh’s GDP to the energy sector. He highlighted the need to increase the renewable energy generation and distribution which can be achieved by greater cooperation with India as the supplier and also, as an intermediary for supply from Nepal and Bhutan.

Ms. Veena Sikri brought to focus the power and energy potential that can be enhanced by India-Bangladesh nuclear energy cooperation along with Russia. She also highlighted the growing technological exchanges between the two countries and the impact it will have on the region at large.

Major General AKM Abdur Rahman in his address categorized the energy cooperation between the two countries as one of the finest. He brought to focus the role hydropower generation can play in strengthening the ties between the two countries, while also contributing to the economic growth and development.

Mr. Guru Prakash in his remarks highlighted the Indian initiatives to address the structural and institutional challenges pertaining to power distribution at the grass-root level that can serve as a guide for Bangladesh. He also mentioned the three verticals of information & communication technology – software, cloud and computing architectures, that can serve as the basis for cooperation.

Mr. Tanvir Shakil Joy in his remark focused on the need to consider the limited availability of fuel running the power plants in Bangladesh and the urgent need to look for alternative fuel to ensure the continuum in economic growth and development. He also said that India can be the most trusted and reliable friend in achieving such aims.

Session IV: Ecological Sustainable Development

Chairperson: MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India.

Keynote Speaker: Veena Sikri, Professor, Ford Foundation; Chair, Bangladesh Studies Program, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi & former High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh, India

Panelists:

- Waseqa Ayesha Khan, Member of the Parliament, Bangladesh

- Sabyasachi Dutta, Secretary, Governing Council, Asian, Confluence, India

- Dr Kamrul Hasan Khan, former Vice Chancellor, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh

- Preeti Saran, former Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India

Mr. MJ Akbar in his initial remarks expressed concerns over human nature as an impediment to achieve goals framed on the premise of sustainable development.

Ms. Veena Sikri stated that economic growth cannot be an end in itself but it has to be seen in context with social development and protection of the environment. As neighbours, coordinated efforts to minimize the reliance on fossil fuels for cross-border trade and instead making use of the shared water resources has been one of the most important achievement of India-Bangladesh relationship in the context of ecological sustainable development. She brought to discussion the possibility of coordinating trade between India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal through the use of water ways as a model for sustainable development for the entire world.

In her address, Ms. Waseqa Ayesha Khan highlighted the common concerns of development that socio-political conditions dictate in Bangladesh and India. Thus, there is a stronger need for the two countries to coordinate and assist each other in developing sustainably. The shared ecology between the two countries including the delta, forest resources and the Bay of Bengal can be protected and developed not in isolation but only through formation of joint committees and agenda.

Reflecting on the shared geography of India and Bangladesh, Mr. Sabyasachi Dutta emphasised on the interconnectedness of the blue economy and the mountain economy of both countries. In his address, he proposed for creation of a Joint Basin Management body to ensure that both the countries while benefitting from the trade potential of the region, are also better positioned to protect the basin by managing sustainable usage.

Prof. Dr Kamrul Hasan Khan brought to discussion the importance of using, protecting and enhancing the community resources so that the ecological processes important for sustaining a good quality life are available for the coming generation. He laid emphasis on the need for joint efforts to revive the ecological resources while planning the growth and developmental agenda by India and Bangladesh.

Ms. Preeti Saran focused on the globally rising sea levels and the impact it has on Bangladesh and the costal states of India. Amidst this challenge, irrational use of the existing biocapacity by both the countries for years have raised serious concerns for the future growth narrative. She also mentioned the potential of natural disaster management cooperation between the two countries, considering their shared ecology and concerns.

Session V: Containing Extreme Ideology for Regional Security

Chairperson: Hasanul Haq Inu, MP, Ex Minister for Information and Broadcasting

Keynote Speaker: Maj Gen A.K. Mohd. Ali Shikder (Retd.), Security Analyst

Panelists:

- Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation, India

- Dr Delwar Hossain, Department of International Studies, Dhaka University

- Dr Sreeradha Datta, Centre Head & Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Vivekananda International Foundation India

- Prashanta B Barua, Director, UK Centre for Bangladesh Studies

Mr. Hasanul Haq Inu commenced the session by recalling India’s contribution in providing traditional sense of security to the Bangladeshi people in early 1970s. Since then both the countries sharing border, also share common security concerns. The most important concern being rise of religious extremism.

In his initial remarks, Maj Gen A.K. Mohd. Ali Shikder laid emphasis on the importance of peace and security as the basis for growth and development of both the countries individually and for the strengthening of bilateral relationship. He brought to discussion the role played by Pakistan for years in disrupting the internal security of India and Bangladesh by sponsoring and exporting terrorism. Secular by constitution, both countries must make coordinated efforts to ensure that the religious colour acquired by terrorism is countered for ensuring peace in the region.

Mr. Prashanta B Barua in his address focused on the role the new evolved form of media, ‘social media’ is playing in facilitating the spread of extreme ideologies. The worst affected are the young minds consuming the hatred propagated by the terrorist groups, who get hypnotised to join such organizations. He laid emphasis on the need for a united societal approach to fight such propaganda through stronger counter-radicalization policies.

Emphasising on the need to introspect, Dr Sreeradha Datta in her address spoke about countering the homegrown terrorist organizations before they form international linkages and expand their presence. Where initially the downtrodden deprived youth were part of the terror nexus, increasingly the privileged youth is also getting attracted to their narrative and hence, there is a need to approach the situation differently.

Dr Delwar Hossain in his address asserted that security is shaped by the cognitive and behavioural faculty of human beings. While the importance of military ecosystem for containing the behavioural aspect of the terrorists cannot be vitiated, past few years have been a testament for the growing need to form policies that can address the cognitive faculty of individuals getting attracted to the extremist narrative. He emphasised on the need to invest more in the people in order to ensure that they are not attracted to extreme ideology.

Attributing extreme ideology as the breeder of violence, Mr. Alok Bansal laid emphasis on the need for increasing tolerance for ambiguity. He emphasised on the need to diversify the ways in with the issues emanating from extreme religious ideologies are seen. In order to counter theological-based terrorist organizations, it is important to form a united regional forum that can counter the theological arguments propagated by the terrorist organizations.

Valedictory Session

The Valedictory Session was chaired by Lt Col Muhammad Faruk Khan (Retd.), Chairman, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh. The Chief Guest for the session was Dr AK Abdul Momen, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh. The session was also graced by the presence of Mr. MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India; Mr. Nahim Razzaq, Member of Parliament, Bangladesh and Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami, Director Techno International Collage of Technology, Working President, Friends of Bangladesh (India Chapter). The vote of thanks was delivered by Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation.

In the keynote address, Dr AK Abdul Momen laid emphasis on the multifaceted nature of India-Bangladesh relationship which is rooted in shared historical and geographical proximity. This relationship is based on the belief in values such as sovereignty, equality, understanding, trust and win-win partnership. The evolving engagements between the two speaks of a maturing and evenly paused relationship. He also said that in light of this strong bond between India and Bangladesh, conscious efforts must be taken to create a mindset of respect, irrespective of dividing variables.

Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami traced the importance track II diplomacy has played for strengthening the India-Bangladesh relationship over the years. In the last few years this relationship has gained a renewed momentum under the leadership of hon’ble Prime Minister Narendra Modi and hon’ble Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Both the countries must strive towards making the most of it for a shared growth and prosperity.

With this the Cox’s Bazar Declaration was adopted and the 9th round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue concluded.

Cox’s Bazaar Declaration

“CONFIGURING THE INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE”

Intent is the engine which defines the outcomes. Taking into consideration the foundational paradigm set in stone by the Sixth Round of the India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue held in New Delhi in the year 2015 and the Seventh Round of the India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue held in Dhaka in the year 2016 – wherein the dialogue has made an attempt to define (a) the participants, (b) the trends, (c) the peripherals, (d) the optics which shape both the economic and the political interaction between the two countries and then assign weights to each component separately across three of the nine major areas, namely, (i) Managing Peaceful and prosperous International Borders and Security, (ii) Water Security and joint Basin Management, (iii) Energy Security and cross border generation and trade in power, (iv) Connectivity and Integrated Multimodal Communication, with special emphasis on utilizing inland waterways, (v) Sub-Regional and Regional development and utilization of mega-architectures such as Regional and Continental Highways, Rail Networks, Sea Ports and Coastal Shipping, (vi) Investment, production, manufacturing and service sector complementarities, (vii) Education and Health Sector Development and elimination of disease, malnutrition, illiteracy and ignorance, (viii) Designing sustainable and forward looking mechanisms in joint finance and marketing of both innovative and high-end value-added products and services, and (ix) Development of leadership across South Asia to institute measurable social and economic changes; the Dialogue has reconvened in Bangladesh for its ninth chapter in Cox’s Bazaar in the year 2019.

The Dialogue in its ninth iteration has come to a consensus that there needs to be an ideational space, which shall henceforth be called the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE, where designs for the interrelationship between the two countries would be drawn based on the learning and experience of the past and expectations and aspirations for the future.

The Dialogue has also come to an agreement that the following areas would play a key role to strengthen the relationship between the two countries:

– First: Trade, Investment to Generate Employment. It is important that states recognize the urgent need to synergize the productive capabilities for movement and employment of citizens across the border. The individual citizen is eager for employment, not only as a service provider, but also as an entrepreneur. The individual wants to be connected and available to the global networks of talent and the state must render due attention to generate and sustain employment and entrepreneurship opportunities across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE.

– Second: Connectivity. The individual citizen wants to travel, to talk and to connect, meaningfully. This is a rising vector of an inalienable right in the global consciousness. Any system or systemic preference which stifles the individual’s propensity to connect beyond borders and boundaries will not only alienate the individual but undermine the very mandate and legality of the regimes in them and must therefore be identified, contained and eradicated.

– Third: Technology, Power and Energy. The individual citizen is either conscious or on the cusp of the awareness of the potential of technology. Any institutional arrangement, which wants to be relevant to the individual and consequently, draw mandates for representing them, ought to carry with itself a tangible promise of technology, not on Internet alone, but on applications and system support to leverage ideas, with solid financial underwriting. Connecting the Gujarat Financial and Technological City Model to one emerging city – such as Mymensingh – might be a test case in this regard.

Both the individual and institutions are energy hungry. Sustainable, eco-friendly, affordable and accessible energy needs have to be met if systemic balances are to be achieved in the long run. Cities are not really concentrated masses of human individuals; rather, they are concentrations of productive and imaginative talent. The urban landscape, as it continues to evolve into denser formations of shared human existence, is also shaping the nature of human evolution as a species. Both countries need to design work and workspaces which can leverage the abundant supply of human talent into mechanisms to meet the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE shall focus, highlight and augment the urbanization process across the two countries where innovations can be incubated, curated and accelerated, the Dialogue agreed.

– Fourth: Ecological Sustainable Development. Across the various parts of the India-Bangladesh terrain, particularly on the sea-front and also in the water-deficit areas, millions of individuals are at risk of seriously adverse changes in climatic conditions. Becoming climate refugees is not a good option for any state. Hence, measurable and verifiable tracks need to be laid to which the individual can relate and subscribe. Finding complementary and systemic solutions for identifying and solving the basic needs of the citizenry across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE, particularly for ensuring access to food, water, sanitation, health, education and jobs, is a high-priority agenda – across the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin, the Dialogue agreed.

– Fifth: Containing Extreme Ideology for Regional Security. The Dialogue agreed that specific and state-sponsored measures need to be devised to contain and “thwart” the propagation and mainstreaming of extremist and belligerent interpretations of religious values and principles. The authority of the state, as enshrined by the constitution, ought to be understood widely and deeply across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE. The Dialogue emphasized the creation of direct information and executive links between central administrations and law enforcement agencies in the real time to ensure that individuals and societies are safe, secure and in a region that can live without fear.

A Safer World and a Secure Relation

The Dialogue agreed that both India and Bangladesh need to continuous strive to ensure that the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE remains firmly rooted in the commitment of both states for ensuring essential human freedoms and on the core values of human rights, democracy, sovereignty, secularism and the rule of law. Together, the countries will build a “strategic space” for the world where there is freedom from fear and where freedom of thought and speech ensure a progressively more comfortable and congenial future for future generations.

The Dialogue will reconvene in India in 2020 for its Tenth Round to conclusively discuss the other identified intervention areas.

The Dialogue hereby concludes its Ninth Iteration on the 2nd day of November, 2019, in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

India Foundation Journal November December 2019

Focus Theme: Security Paradigm in South Asia