India Foundation Journal January February 2020

Focus: Theme: The Constitution of India : Contemporary Issues?

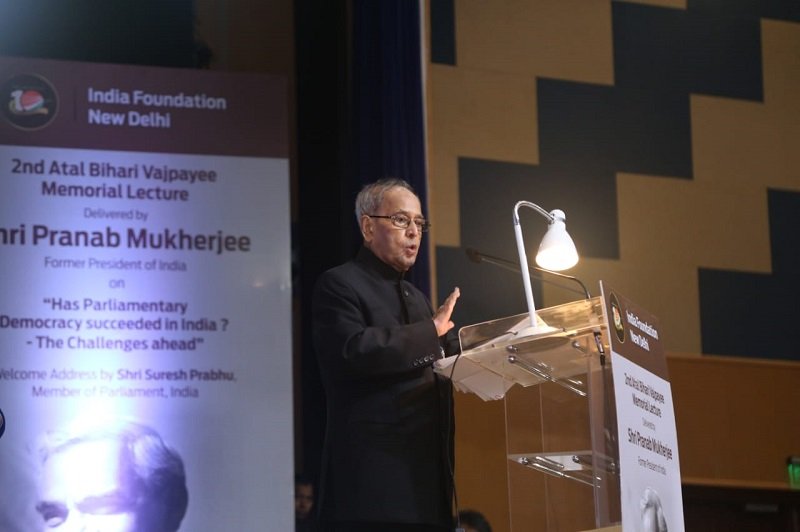

2nd Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture

India Foundation instituted the India Foundation instituted the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture in 2018 to celebrate the legacy of the Former Prime Minister of India Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Shri Vajpayee personified the spirit of nationalism, integrity in public life and approach towards politics.

The First Lecture was delivered by Former Finance Minister of India Shri Arun Jaitley in Delhi on the theme of “Indian Democracy: Maturity and Challenges” at the 4th India Ideas Conclave in 2018.

The Second Atal Bihari Vajpayee Memorial Lecture was delivered by the Former President of India Shri Pranab Mukherjee on December 16, 2019 in New Delhi, India. The theme of the second lecture was “Has Parliamentary Democracy Succeeded in India and the Challenges Ahead”.

Former President Mukherjee spoke of his admiration for Atal Ji for his innate qualities of being an orator, moderator and consensus seeker. Speaking of the evolution of parliamentary system in India, Shri Mukherjee spoke of three phases of British influence phase of post independence India; multi-party coalition stage of 1990s and the third phase where the multi-party system slowly started changing to a bipolar system where in two major coalition blocks came to dominate Indian polity after the elections of 1998. He, however, went on to commended the fine balance between electoral majority and majoritarianism that the parliamentary system in India has achieved.

He concluded by highlighting the shortcomings of the system and expressing hope that that Parliament of India will live up to the task of ensuring that Indian democracy provides for an enabling environment which helps every section of the society to fully participate in the process of governance.

The Address was attended by over 300 eminent citizens from all walks of life. The audience comprised of Ministers, Member of Parliaments, Bureaucrats, Political Leaders, Diplomats, Media Personalities, Corporate Leaders, Academics and Scholars.

If not Democracy, then what?

Anti-CAA demonstrations took a violent turn in some Muslim dominated districts of the country. Rowdy crowds have inflicted huge damages on public property. This raises an important question. Have the people of this country taken to the spirit of democracy during the seventy-three years of popular governance? In the course of its long stint in power since independence, the Congress has been claiming with great élan that it is making an enviable experiment of moderating Indian Muslims by using a proven tool called secular democratic dispensation as is enshrined in the Constitution. The objective has been to help the Muslim community integrate into the national mainstream. In other words, Congress meant to assert that Islam and democracy/secular democracy, seemingly a contradiction in terms, are reconcilable. The intentions were unassailable, and as a matter of simple logic, if any segment of Indian Muslims doubts or contradicts the paradigm, the logic will not be on their side.

Nevertheless, the sudden outburst, first at three or four universities in the country, with the Muslim tag appended to them notionally or virtually, and then the escalation of violence and vandalism in almost all important Muslim dominated pockets in various states of the country, ruthlessly demolished the edifice of de-radicalising of Indian Muslim community which the Congress claims it assiduously built over decades by adopting pro-Muslim pacifist and even solicitous policies at different levels. Many a time, the national mainstream expressed unease at this overdone conciliatory stance. Nevertheless, standing by its characteristic quality of tolerance, the masses of Indian people did not make an issue out of the ongoing large scale vandalising that could have the potential of disrupting and endangering civilian life and property.

The misfortune of the Congress is that after its grand old titans phased away, and the second and third rung leadership donned the mantle, it gradually dawned upon them that they were far behind their pioneers in popularity and public response. The generation gap was wide enough and would not let them cash on the big names for all times. Therefore, a new mechanism of retaining political ascendency had to be created. Simultaneously, they were confronted with the emergence of a new socio-political phenomenon called the culture of identity in the Indian civil society. It posed a serious challenge to the popularity and status of the traditional Congress party. After all, the impact of the steady growth of the Indian economy could not be underestimated. The rise of the culture of identity was a glaring manifestation of that impact. The task of the Congress to maintain its supremacy was becoming more and more arduous.

Unfortunately, the Congress, looking out for political crutches, committed the grave blunder of shifting its ideological goalpost from passionate and universal nationalism to the narrow confines of the national minority of Indian Muslims. In doing so, it first deliberately built the “oppressed, discriminated and deprived” profile of the Indian Muslim community, and then, on that premise, began to legitimise its policy of appeasement and pusillanimity towards the Muslim community. This was the beginning of an ugly and disastrous phase of Indian democracy, namely the vote bank politics. In carrying forward this policy, Congress, out of sheer lust for power, created an icon (Indian nationalism) to whose doorsteps it would bring all imaginable blames.

They branded the Indian nationalists variously like “tyrannical majority,” “Hindu terrorism” and even “Nazi dictatorship”. With that, the Congress party claimed that only they could provide security and prosperity to the Muslims of India while the rest of them, particularly the nationalists, were their detractors. Had Congress confined itself to the economic and social uplift of the Muslims of India and not created a political concoction, it would have immensely contributed to the integration of the Muslims into the national mainstream. The street rages and vandalism that we see today in Muslim dominated sectors in the entire country is what the Congress and its close associate the Left, nurtured for so many decades. They sadistically sowed the wind and the Indian nation must now reap the whirlwind.

If the Muslims of India have remained outside the national mainstream, the cause is firstly the wrong approach of Congress and secondly the absence of right-thinking leadership among the Indian Muslims. By succumbing to the egotistic socio-political philosophy of the Congress, the Muslims of India not only sidelined themselves from the national mainstream but also unwittingly created a wedge between them and the national majority. The widespread protestation by a section of the Indian Muslims that has emerged in the aftermath of CAA is part of the political game of Congress and its dissenting allies to create disorder in the country. It will be noted that Congress has resorted to these tactics after it exhausted all other options of derailing the elected government at the Centre.

It is for the first time since independence that some Indian Muslims have come out openly and violently against the elected government in the country and against the sovereignty of the Indian Parliament. Interestingly, the anti-India and anti-Indian majority campaign is being waged while brandishing the Indian tricolour, unlike the Kashmiris who generally brandish either the black or the Pakistani/ISIS flags in their anti-India demonstrations. Waging violent demonstrations under the shadow of Indian tricolour is certainly a method in the madness called takkiya in Islamic terminology.

By these exclusivist protest rallies, this section of Indian Muslims have indicated that they reject the Indian secular democratic dispensation as did the founders of Pakistan seven decades ago. The question is: If this section of Indian Muslims do not want a democratic dispensation, what do they want then? Do they want to force the Indian nation to ask for a declaration of India as a Hindu state like Pakistan? We have a word of admiration for the Modi government which did not lose its cool during the ongoing scenes of vandalism, arson, loot and violence in the country. This is how the government of the world’s largest democracy should behave. The Hindu community leaders equally deserve appreciation for not allowing the masses of people to go mad after a handful of miscreants. How regrettable that the chief of the Congress has publicly announced her party’s support to the students but has not said a word of warning or advising them to desist from vandalism, and respect the law of the land. She clings to the vote bank, and surprisingly she learnt nothing from her son having to run away from his traditional constituency in UP to a predominantly Muslim dominated constituency in Kerala. It appears that Ms Gandhi needs to support the elements in or out of the country that aspires and work for disintegration of India.

The widespread protestation by the Indian Muslims is not just a local affair. We are aware of various inimical forces on the international plane working towards the breaking of the Indian Union. After having played and exhausted its role in the Middle East, the rabid Islamic jihadists and suicide squads have shifted the scene of the contemporary war of civilisations from the Middle East to India. The concentration of all terrorist jihadists and suicide bombers of Pakistan along the Indo-Pak border, Pakistan’s repeated threats of using weapons of mass destruction, China’s dangerous posture in the Indo-Pacific oceanic region, outright anti-India stance of Turkey, Egypt and Malaysia, and the vast scale propaganda and disinformation unleashed by sections of biased national and international media, all point toward a global conspiracy purporting to destabilise the elected government in New Delhi and disintegrate the Union of India just because Indian Prime Minister is fighting Islamic terror at many world forums. Many countries are enviously looking at India’s growing economic and scientific power as a challenge to their status in the international arena. Many anti-national elements within the country or the Urban Naxals are accomplices in these perfidious acts. It is a shame for the opposition, one and all, that at a time when our enemies on the west and the east have forged an unholy alliance and are poised to strike at India in various ways, the opposition is contributing to its own disaster.

It must be noted that the protestation methodology adopted by anti-CAA crowds country-wide, is precisely the replication of the methodology adopted by the Kashmiri militants, dissidents and secessionists viz. stone-throwing and attacks on the police, torching public property and public and private vehicles, using black masks to avoid identification, contriving media, males disguising as females, raising slogans of ‘Azadi’ and responding to police authorities by saying that their respective localities are peace-loving but miscreants come from other localities etc. The only difference is that while the Kashmiris raised Pakistani or ISIS flags, the Indian Muslim crowds raised the tricolor only to be humiliated rather than respected.

This perfidy has to be uprooted. History has shown that the Indian nation has the inherent strength to survive through cataclysms and catastrophes. Today, the nation is in the hands of an honest, able and bold leadership, led by a man of the masses. Indian Sanskriti, disowned and then despised and reviled by the invaders is reborn and will thrive in full glory. This Sanskriti is the common heritage of all those who call themselves Indians. That is why, it behoves the Muslims of the country not be misled by a few disgruntled elements amongst them who preach vitriolic hate and strive to weaken the nation through a divisive ideology and through vandalism. These elements are doing great harm to the Muslim community, which needs to stand up and reject their hate-filled ideology. It is time for all Indians to rise as one and build the foundations of a strong country.

*The writer is the former Director of the Centre of Central Asian Studies, Kashmir University

Roundtable discussion on India-Vietnam Relations

Wordpress is loading infos from thehindu

Please wait for API server guteurls.de to collect data fromwww.thehindu.com/news/national/...

India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue by India Foundation

Special Address by Hon’ble Tony Abbott, Former Prime Minister of Australia, on “Vision for a Free & Open Indo-Pacific Date: 18 November 2019

Conference on India-Myanmar Relations on theme “Connecting India’s Northeast with North West Region of Myanmar: Roadmap for all round prosperity”.

Round-table Discussion on “The Chennai Spirit: India-China Relations”

Report of the Ninth Round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue

November 1-2, 2019

Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh

Configuring The Bangladesh-India Strategic Space

Inaugural Session

Building on the strong foundations of India-Bangladesh bilateral ties, the ninth round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue commenced on November 1, 2019 at Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. This round was organized by India Foundation and Bangladesh Foundation for Regional Studies. It was supported by Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh and Friends of Bangladesh. The event commenced with a pre-conference interaction to highlight the goals and achievements of the Dialogue. This interaction was led by Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh and Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation.

The inaugural session was graced by the presence of Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury, Hon’ble Speaker, Bangladesh Parliament; Mr. Ram Madhav Varanasi, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party & Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation; Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh; Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma, Hon’ble Minister for Finance, Transformation and Development, Health and Family Welfare, PWD, Government of Assam, India; Mr. MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India; Ms. Riva Ganguly Das, High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh; Mr. M. Shahidul Islam, Secretary General, BIMSTEC; Md. Shahidul Haque, Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh; Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami, Director Techno International College of Technology and Working President, Friends of Bangladesh (India Chapter); and Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation. The inaugural ceremony also witnessed the presence of several other esteemed and learned dignitaries from Bangladesh, along with the delegation from India.

Mr. MJ Akbar credited the last five dialogues with achieving more success in bringing the two nations closer as compared to the relations between the two in the last 20-25 years. Md. Shahriar Alam highlighted the multifaceted relationship between the two countries rooted in the shared history and geographical proximity. He underscored the civilizational, cultural and socio-economic links and consequently, the commonalities between the two. Listing new areas of cooperation, Hon’ble minister regarded it as an example of maturing India- Bangladesh relationship.

Mr. M. Shahidul Islam focused on his strong belief that a sound relation between India-Bangladesh is conducive to the peace, progress and prosperity of the entire BIMSTEC region. He said that in an increasingly interdependent world, the cherished ideals of peace, freedom and economic well being are best attained by fostering greater understanding, good neighbourliness and meaningful cooperation among the countries of the same sub-region already bound by ties of history and culture.

Ms. Riva Ganguly Das while highlighting the various nuances of India-Bangladesh relations, focused on the trajectory followed by India in becoming the net employment generator in Bangladesh, while also indulging in capacity development. She brought into discussion the various projects undertaken that will forge stronger connectivity ties between Bangladesh and the North-Eastern states of India.

Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma in his address appreciated the efforts of Her Excellency Sheikh Hasina’s government in fighting terrorism, which have immensely contributed to the peaceful and secure economic prosperity of Assam. Concentrating on the geographical proximity of Bangladesh with the North-Eastern states, he urged the Bangladeshi government to take proactive measures to strengthen trade and commerce in the region.

Mr. Ram Madhav Varanasi commenced his address by highlighting the commonalities between the two countries in reinstating faith in their national leaders and designing national agendas on similar themes to strengthen their respective countries, while also reinforcing the bilateral relationship. He traced the relationship between he two countries to be built on sentiments, beyond the tangible contents of several agreements signed between the governments. He highlighted that the relationship transcends the nuances of a strategic partnership and is deeply rooted in strong historical and fraternal ties based on sovereignty, equality, trust and understanding.

Dr. Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury focused on the comprehensive scope of the theme for the ninth round of the dialogue. Describing the ‘Bangladesh-India Strategic Space’ as an innovative concept of cooperation, she regarded it as a notional setup providing framework within which issues of mutual cooperation can be fitted in and taken forward in a planned and methodological manner to attain shared goals. She highlighted the need to keep working together and be responsive to the emerging challenges to ensure that the two countries can grow with shared prosperity, while also formulating innovative modes to resolve the pending issues amicably and peacefully.

The vote of thanks was delivered by Shri. Alok Bansal. This was followed by a cultural programme showcasing the rich heritage of India and Bangladesh. Thereafter, dinner was hosted by AJM Nasir Uddin, Mayor, Chattogram City Corporation.

Session I: Trade, Investment to Generate Employment

Chairperson: Md. Shahriar Alam, State Minister for Foreign Affairs, Government of Bangladesh

Keynote Speaker: Dr Atiur Rahman, Department of Development Studies, Dhaka University & Former Governor, Bangladesh Bank

Panelists:

- Kushan Mitra, Managing Editor, The Pioneer, India

- Dr Nazneen Ahmed, Senior Research Fellow, BIDS, Bangladesh

- Preeti Saran, Former Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs, India

- Tarik Hasan, Treasurer, Suchinta Foundation, Bangladesh

Md. Shahriar Alam in his initial remarks categorized poverty as the biggest enemy for both the governments and ensuring trade and investment that can generate employment as amongst the most important tools to combat it.

Dr Atiur Rahman presented the initiation paper on the theme for the session and highlighted the unprecedented level of willingness to cooperate shown by the governments. He deliberated on the need to broaden the trade infrastructure, digital and other forms of connectivity which will generate employment both directly and indirectly, while also contributing to the economic growth story of both the countries.

Mr. Kushan Mitra focused his remarks on the automotive industry and the start-up ecosystem. He stated that there is immense potential in improving the ease of doing business in both the countries and that both should learn from each others experience, while also facilitating policy suggestions and adaptation to the other.

Dr Nazneen Ahmed stressed on the strategic importance of growing young population in both the countries. She highlighted the need to facilitate in setting up not just educational institutions, but also other forms of institutional designs that can provide access to information and opportunities to enhance their employability.

Ms. Preeti Saran expressed her concerns over the unrealized potential of trade between India and Bangladesh, despite the quantum having increased by nearly three folds. Inland waterways is one such sector, the investment in which will have direct bearing on the overall trade narrative and employment opportunities.

Mr. Tarik Hasan in his remarks focused on the need to ensure competitive value for exports in both India and Bangladesh to build on the existing trade and commerce exchange. He also focused on the need to proactively engage Bangladesh with the North-Eastern part of India to tap the unrealized potential.

Session II: Connectivity

Chairperson: Himanta Biswa Sarma, Hon’ble Minister for Finance, Transformation and Development, Health and Family Welfare, PWD, Government of Assam, India

Keynote Speaker: Dr Sreeradha Dutta, Centre Head and Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Vivekananda International Foundation, India

Panelists:

- Dr Atiur Rahman, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Dr Joyeeta Bhattacharjee, Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Regional Studies Initiative, ORF, India

- Dr Delwar Hossain, Department of International Relations, Dhaka University, Bangladesh

- Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation

Mr. Himanta Biswa Sarma in his initial remarks reiterated the commitment of Shri. Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India to bring transformation by facilitating transportation. He highlighted the impact of a strong infrastructure of highway, internet, railway and airway on relations between two countries.

Dr Sreeradha Dutta initiated her address by bringing to light that connectivity begins with the convergence of ideas, thoughts, interests and values, which ultimately develops the infrastructure and transportation. She highlighted the need to work on the logistical infrastructure on both side of the border, while also ensuring a strict mechanism to deal with security threats disrupting trade.

Dr Atiur Rahman provided a different spectrum to understand the connectivity between India and Bangladesh. He focused on the important role that agriculture and horticulture can play in strengthening the cooperation in supply-chain management. He urged to improve the connectivity by making borders the access points, facilitating an easier visa regime and focusing also on educational connectivity.

Dr Joyeeta Bhattacharjee in her address spoke about the importance of connectivity through information. She focused on the need to work positively towards the changing perception about each other in the two countries, while also ensuring that connectivity is not just seen from the lens of hard infrastructure, but also through the soft lens of people, ideas and minds.

Dr Delwar Hossain emphasised on the trajectory that made connectivity a basis for strong India-Bangladesh relations. He focused on the need to add financial connectivity as a paradigm while analysing connectivity between the two countries. There is a pressing need to smoothen financial transactions across the borders and develop new modes of connectivity for shared economic prosperity and growth.

Mr. Alok Bansal in his address focused on the need to enhance connectivity to ensure that the two growing economies, India and Bangladesh can live up to their true potential, especially between the North-Eastern region of India and Bangladesh, owing to their existing geographical proximity and cultural similarities. He also emphasised on the need to shift the transport of bulk freight from road to rails in order to facilitate trade of perishable goods and consider the idea of building a tourist grid to connect the two countries.

Session III: Technology, Power and Energy

Chairperson: Muhammad Nazrul Islam, Bir Protik, former State Minister for Water Resources, Bangladesh

Keynote Speaker: Md Abdul Aziz Khan, Member, Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission

Panelists:

- Veena Sikri, Professor, Ford Foundation, Chair, Bangladesh Studies Program, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi & former High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh, India

- Major General AKM Abdur Rahman, Director General, Bangladesh Institute of International and Strategic Studies

- Guru Prakash, Assistant Professor, Patna University & Advisor, Dalit Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, India

- Tanvir Shakil Joy, former Member of Parliament & Former Convener of Climate Parliament, Bangladesh

Muhammad Nazrul Islam discussed the importance of technology, power and energy for strengthening the India-Bangladesh cooperation.

Md Abdul Aziz Khan in his initial remark attributed a significant proportion of the tremendous growth of Bangladesh’s GDP to the energy sector. He highlighted the need to increase the renewable energy generation and distribution which can be achieved by greater cooperation with India as the supplier and also, as an intermediary for supply from Nepal and Bhutan.

Ms. Veena Sikri brought to focus the power and energy potential that can be enhanced by India-Bangladesh nuclear energy cooperation along with Russia. She also highlighted the growing technological exchanges between the two countries and the impact it will have on the region at large.

Major General AKM Abdur Rahman in his address categorized the energy cooperation between the two countries as one of the finest. He brought to focus the role hydropower generation can play in strengthening the ties between the two countries, while also contributing to the economic growth and development.

Mr. Guru Prakash in his remarks highlighted the Indian initiatives to address the structural and institutional challenges pertaining to power distribution at the grass-root level that can serve as a guide for Bangladesh. He also mentioned the three verticals of information & communication technology – software, cloud and computing architectures, that can serve as the basis for cooperation.

Mr. Tanvir Shakil Joy in his remark focused on the need to consider the limited availability of fuel running the power plants in Bangladesh and the urgent need to look for alternative fuel to ensure the continuum in economic growth and development. He also said that India can be the most trusted and reliable friend in achieving such aims.

Session IV: Ecological Sustainable Development

Chairperson: MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India.

Keynote Speaker: Veena Sikri, Professor, Ford Foundation; Chair, Bangladesh Studies Program, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi & former High Commissioner of India to Bangladesh, India

Panelists:

- Waseqa Ayesha Khan, Member of the Parliament, Bangladesh

- Sabyasachi Dutta, Secretary, Governing Council, Asian, Confluence, India

- Dr Kamrul Hasan Khan, former Vice Chancellor, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Bangladesh

- Preeti Saran, former Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India

Mr. MJ Akbar in his initial remarks expressed concerns over human nature as an impediment to achieve goals framed on the premise of sustainable development.

Ms. Veena Sikri stated that economic growth cannot be an end in itself but it has to be seen in context with social development and protection of the environment. As neighbours, coordinated efforts to minimize the reliance on fossil fuels for cross-border trade and instead making use of the shared water resources has been one of the most important achievement of India-Bangladesh relationship in the context of ecological sustainable development. She brought to discussion the possibility of coordinating trade between India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal through the use of water ways as a model for sustainable development for the entire world.

In her address, Ms. Waseqa Ayesha Khan highlighted the common concerns of development that socio-political conditions dictate in Bangladesh and India. Thus, there is a stronger need for the two countries to coordinate and assist each other in developing sustainably. The shared ecology between the two countries including the delta, forest resources and the Bay of Bengal can be protected and developed not in isolation but only through formation of joint committees and agenda.

Reflecting on the shared geography of India and Bangladesh, Mr. Sabyasachi Dutta emphasised on the interconnectedness of the blue economy and the mountain economy of both countries. In his address, he proposed for creation of a Joint Basin Management body to ensure that both the countries while benefitting from the trade potential of the region, are also better positioned to protect the basin by managing sustainable usage.

Prof. Dr Kamrul Hasan Khan brought to discussion the importance of using, protecting and enhancing the community resources so that the ecological processes important for sustaining a good quality life are available for the coming generation. He laid emphasis on the need for joint efforts to revive the ecological resources while planning the growth and developmental agenda by India and Bangladesh.

Ms. Preeti Saran focused on the globally rising sea levels and the impact it has on Bangladesh and the costal states of India. Amidst this challenge, irrational use of the existing biocapacity by both the countries for years have raised serious concerns for the future growth narrative. She also mentioned the potential of natural disaster management cooperation between the two countries, considering their shared ecology and concerns.

Session V: Containing Extreme Ideology for Regional Security

Chairperson: Hasanul Haq Inu, MP, Ex Minister for Information and Broadcasting

Keynote Speaker: Maj Gen A.K. Mohd. Ali Shikder (Retd.), Security Analyst

Panelists:

- Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation, India

- Dr Delwar Hossain, Department of International Studies, Dhaka University

- Dr Sreeradha Datta, Centre Head & Senior Fellow, Neighbourhood Studies, Vivekananda International Foundation India

- Prashanta B Barua, Director, UK Centre for Bangladesh Studies

Mr. Hasanul Haq Inu commenced the session by recalling India’s contribution in providing traditional sense of security to the Bangladeshi people in early 1970s. Since then both the countries sharing border, also share common security concerns. The most important concern being rise of religious extremism.

In his initial remarks, Maj Gen A.K. Mohd. Ali Shikder laid emphasis on the importance of peace and security as the basis for growth and development of both the countries individually and for the strengthening of bilateral relationship. He brought to discussion the role played by Pakistan for years in disrupting the internal security of India and Bangladesh by sponsoring and exporting terrorism. Secular by constitution, both countries must make coordinated efforts to ensure that the religious colour acquired by terrorism is countered for ensuring peace in the region.

Mr. Prashanta B Barua in his address focused on the role the new evolved form of media, ‘social media’ is playing in facilitating the spread of extreme ideologies. The worst affected are the young minds consuming the hatred propagated by the terrorist groups, who get hypnotised to join such organizations. He laid emphasis on the need for a united societal approach to fight such propaganda through stronger counter-radicalization policies.

Emphasising on the need to introspect, Dr Sreeradha Datta in her address spoke about countering the homegrown terrorist organizations before they form international linkages and expand their presence. Where initially the downtrodden deprived youth were part of the terror nexus, increasingly the privileged youth is also getting attracted to their narrative and hence, there is a need to approach the situation differently.

Dr Delwar Hossain in his address asserted that security is shaped by the cognitive and behavioural faculty of human beings. While the importance of military ecosystem for containing the behavioural aspect of the terrorists cannot be vitiated, past few years have been a testament for the growing need to form policies that can address the cognitive faculty of individuals getting attracted to the extremist narrative. He emphasised on the need to invest more in the people in order to ensure that they are not attracted to extreme ideology.

Attributing extreme ideology as the breeder of violence, Mr. Alok Bansal laid emphasis on the need for increasing tolerance for ambiguity. He emphasised on the need to diversify the ways in with the issues emanating from extreme religious ideologies are seen. In order to counter theological-based terrorist organizations, it is important to form a united regional forum that can counter the theological arguments propagated by the terrorist organizations.

Valedictory Session

The Valedictory Session was chaired by Lt Col Muhammad Faruk Khan (Retd.), Chairman, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh. The Chief Guest for the session was Dr AK Abdul Momen, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh. The session was also graced by the presence of Mr. MJ Akbar, Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India; Mr. Nahim Razzaq, Member of Parliament, Bangladesh and Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami, Director Techno International Collage of Technology, Working President, Friends of Bangladesh (India Chapter). The vote of thanks was delivered by Mr. Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation.

In the keynote address, Dr AK Abdul Momen laid emphasis on the multifaceted nature of India-Bangladesh relationship which is rooted in shared historical and geographical proximity. This relationship is based on the belief in values such as sovereignty, equality, understanding, trust and win-win partnership. The evolving engagements between the two speaks of a maturing and evenly paused relationship. He also said that in light of this strong bond between India and Bangladesh, conscious efforts must be taken to create a mindset of respect, irrespective of dividing variables.

Dr. Radha Tomal Goswami traced the importance track II diplomacy has played for strengthening the India-Bangladesh relationship over the years. In the last few years this relationship has gained a renewed momentum under the leadership of hon’ble Prime Minister Narendra Modi and hon’ble Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Both the countries must strive towards making the most of it for a shared growth and prosperity.

With this the Cox’s Bazar Declaration was adopted and the 9th round of Bangladesh-India Friendship Dialogue concluded.

Cox’s Bazaar Declaration

“CONFIGURING THE INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE”

Intent is the engine which defines the outcomes. Taking into consideration the foundational paradigm set in stone by the Sixth Round of the India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue held in New Delhi in the year 2015 and the Seventh Round of the India Bangladesh Friendship Dialogue held in Dhaka in the year 2016 – wherein the dialogue has made an attempt to define (a) the participants, (b) the trends, (c) the peripherals, (d) the optics which shape both the economic and the political interaction between the two countries and then assign weights to each component separately across three of the nine major areas, namely, (i) Managing Peaceful and prosperous International Borders and Security, (ii) Water Security and joint Basin Management, (iii) Energy Security and cross border generation and trade in power, (iv) Connectivity and Integrated Multimodal Communication, with special emphasis on utilizing inland waterways, (v) Sub-Regional and Regional development and utilization of mega-architectures such as Regional and Continental Highways, Rail Networks, Sea Ports and Coastal Shipping, (vi) Investment, production, manufacturing and service sector complementarities, (vii) Education and Health Sector Development and elimination of disease, malnutrition, illiteracy and ignorance, (viii) Designing sustainable and forward looking mechanisms in joint finance and marketing of both innovative and high-end value-added products and services, and (ix) Development of leadership across South Asia to institute measurable social and economic changes; the Dialogue has reconvened in Bangladesh for its ninth chapter in Cox’s Bazaar in the year 2019.

The Dialogue in its ninth iteration has come to a consensus that there needs to be an ideational space, which shall henceforth be called the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE, where designs for the interrelationship between the two countries would be drawn based on the learning and experience of the past and expectations and aspirations for the future.

The Dialogue has also come to an agreement that the following areas would play a key role to strengthen the relationship between the two countries:

– First: Trade, Investment to Generate Employment. It is important that states recognize the urgent need to synergize the productive capabilities for movement and employment of citizens across the border. The individual citizen is eager for employment, not only as a service provider, but also as an entrepreneur. The individual wants to be connected and available to the global networks of talent and the state must render due attention to generate and sustain employment and entrepreneurship opportunities across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE.

– Second: Connectivity. The individual citizen wants to travel, to talk and to connect, meaningfully. This is a rising vector of an inalienable right in the global consciousness. Any system or systemic preference which stifles the individual’s propensity to connect beyond borders and boundaries will not only alienate the individual but undermine the very mandate and legality of the regimes in them and must therefore be identified, contained and eradicated.

– Third: Technology, Power and Energy. The individual citizen is either conscious or on the cusp of the awareness of the potential of technology. Any institutional arrangement, which wants to be relevant to the individual and consequently, draw mandates for representing them, ought to carry with itself a tangible promise of technology, not on Internet alone, but on applications and system support to leverage ideas, with solid financial underwriting. Connecting the Gujarat Financial and Technological City Model to one emerging city – such as Mymensingh – might be a test case in this regard.

Both the individual and institutions are energy hungry. Sustainable, eco-friendly, affordable and accessible energy needs have to be met if systemic balances are to be achieved in the long run. Cities are not really concentrated masses of human individuals; rather, they are concentrations of productive and imaginative talent. The urban landscape, as it continues to evolve into denser formations of shared human existence, is also shaping the nature of human evolution as a species. Both countries need to design work and workspaces which can leverage the abundant supply of human talent into mechanisms to meet the challenges of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE shall focus, highlight and augment the urbanization process across the two countries where innovations can be incubated, curated and accelerated, the Dialogue agreed.

– Fourth: Ecological Sustainable Development. Across the various parts of the India-Bangladesh terrain, particularly on the sea-front and also in the water-deficit areas, millions of individuals are at risk of seriously adverse changes in climatic conditions. Becoming climate refugees is not a good option for any state. Hence, measurable and verifiable tracks need to be laid to which the individual can relate and subscribe. Finding complementary and systemic solutions for identifying and solving the basic needs of the citizenry across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE, particularly for ensuring access to food, water, sanitation, health, education and jobs, is a high-priority agenda – across the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin, the Dialogue agreed.

– Fifth: Containing Extreme Ideology for Regional Security. The Dialogue agreed that specific and state-sponsored measures need to be devised to contain and “thwart” the propagation and mainstreaming of extremist and belligerent interpretations of religious values and principles. The authority of the state, as enshrined by the constitution, ought to be understood widely and deeply across the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE. The Dialogue emphasized the creation of direct information and executive links between central administrations and law enforcement agencies in the real time to ensure that individuals and societies are safe, secure and in a region that can live without fear.

A Safer World and a Secure Relation

The Dialogue agreed that both India and Bangladesh need to continuous strive to ensure that the INDIA-BANGLADESH STRATEGIC SPACE remains firmly rooted in the commitment of both states for ensuring essential human freedoms and on the core values of human rights, democracy, sovereignty, secularism and the rule of law. Together, the countries will build a “strategic space” for the world where there is freedom from fear and where freedom of thought and speech ensure a progressively more comfortable and congenial future for future generations.

The Dialogue will reconvene in India in 2020 for its Tenth Round to conclusively discuss the other identified intervention areas.

The Dialogue hereby concludes its Ninth Iteration on the 2nd day of November, 2019, in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh.

India Foundation Journal November December 2019

Focus Theme: Security Paradigm in South Asia

4th Indian Ocean Conference – IOC 2019

Report of the 4th Indian Ocean Conference – IOC 2019

03-04 September 2019

Maldives

The 4th Indian Ocean Conference – IOC 2019 was organised by India Foundation in association with the Foreign Service Institute of Maldives (FOSIM), and S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Singapore on September 3-4, 2019 in the Maldives. The theme for this edition of the Conference was “Securing the Indian Ocean Region: Traditional and Non-Traditional Challenges”.

The Conference was addressed by speakers from over 36 countries including Ministers from 17 countries, and Officials from 15 countries and was attended by delegates from over 40 countries.

First Day of the Conference started with parallel discussions on sub-themes of Navigational Security, Terrorism and Marine Ecology. The first symposium on Navigational Security was Chaired by Capt (IN) Alok Bansal, Director, India Foundation. The speakers were Dr Sanjaya Baru, Distinguished Fellow, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, India; Vice Admiral Anup Singh, Former C-inC, Eastern Naval Command, Indian Navy; Phil Midland, Former Naval Officer, USA and J B Vowell, Deputy Director, Planning and Policy, Indo-Pacific Command, USA

The second parallel symposium on Terrorism was Chaired by Prof S D Muni, Professor (Emeritus), School of International Studies, JNU. The session was addressed by Ms Prabha Rao, Executive Director, South Asian Institute for Strategic Affairs (SAISA), India; Admiral Jayantha Perera, Admiral, I M F and Former Commander of the Sri Lankan Navy; Lt Gen Syed Ata Hasnain, Former GOC, 15 and 21 Corps, Indian Army and Dr Klaus Lange, Director, Institute of Transnational Studies, Germany

The next two parallel sessions were on Navigational Security and an Ambassadors’ Panel to discuss the developments in IOR. The session on Navigational Security was Chaired Dr C Raja Mohan, Director, Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore and was addressed by Ms Preeti Saran, Former Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India; Ms Nisha Biswal, President, US India Business Council, USA; Dr Yan Yan, Director, Research Center of Oceans Law and Policy, National Institute for the South China Sea Studies, China and Mr Sinderpal Singh, Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the South Asia Programme, Institute of Defence and Security Studies, RSIS, Singapore.

The Ambassador’s Panel was chaired by Mr Rajiv Sikri, Former Ambassador of India. The Panel was also addressed by Amb Shin Bong-Kil, Ambassador of South Korea to India; Amb Rita Giuliana Mannella, Ambassador of Italy to Sri Lanka; Amb Vicente Vivencio T. Bandillo, Ambassador of Philippines to Bangladesh and Amb Southam Sakonniyom, Former Ambassador of Lao PDR to India.

Inaugural session of the 4th Indian Ocean Conference

Inaugural Session

The Inaugural Session of the Conference was addressed by H.E. Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, President of Maldives; H.E. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister, Sri Lanka; Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Singapore; Dr S Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister of India and Abdulla Shahid, Foreign Minister of Maldives.

Dr S Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister of India delivered the Welcome Address at the Inaugural Session of the Conference.

Addressing the Inaugural Session of the Conference, H.E Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, President of Maldives, spoke of the importance of navigational security to the security and well being of the Maldives. He then spoke of preserving the integrity and diversity of marine ecology as another crucial priority area for the collective security of the region. Particularly alarming for the Maldives has been a steep decline in the Indian Ocean’s fish stocks. He concluded by reiterating the commitment of his government to engage proactively on every single one of the substantial policy issues relevant to the Indian Ocean.

H.E. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister, Sri Lanka commenced his address by highlighting that the world is becoming increasingly uncertain and facing a triad of critical threats. Amongst these, one of the most critical is the possibility of the downturn of the global economy since the financial crisis. The global dynamics are shifting, and the rise of new powers is creating an asymmetric bipolar world with US and China leading these tensions. With the increasing competition amongst many players, maritime players need to realize the risk associated with destabilizing the maritime order as there is binding economic order that necessitates a greater degree of restraint and cooperation.

Recalling the first edition of the Conference in 2016 Dr Vivian Balakrishnan, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Singapore said that, then there were already signs of fraying of the existing international order. The collective commitment to international security and multilateralism had started to waiver and to add to this the ongoing evolution of the 4th Industrial revolution and the changes it has demanded of our citizens poses greater challenges. He concluded by saying that we all want an India Ocean built on Peace, Security, Stability and Security. It has remained committed to facilitating dialogue, building trust and strengthening multilateral institutions.

Abdulla Shahid, Foreign Minister of Maldives delivered the Vote of Thanks and expressed gratitude on behalf of the Organising Committee of IOC 2019, towards all Heads of States, Ministers, Officials, Scholars and all other dignitaries for having graciously accepted the invite and attended the Conference.

Keynote Session addressed by Dr S. Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister, India and Mr Abdulla Shahid, Foreign Minister, Maldives.

Conference Keynote Session

The Conference Keynote Session was addressed by Dr S. Jaishankar, External Affairs Minister, India and Abdulla Shahid, Foreign Minister, Maldives

Delivering the Conference KeynoteAddress Dr S Jaishankar reaffirmed that India will no longer be limited in the pursuit of its interest to its immediate neighbourhood. And, the same is being reflected in the forging of security relationships in the Pacific that parallel growing economic engagement. He conceptually justified India’s expanding interest in the region by highlighting that India’s core-interests lie in the Indian Ocean and thus a presence beyond also contributes to ensuring a peaceful periphery. Talking about the SAGAR vision, he drew attention to the fact that, SAGAR derives a more active and outcome-oriented Indian approach that enhances this influence by delivering on partnerships.

Taking the stage to address the Conference Keynote Session, Foreign Minister of Maldives, Shri Abdulla Shahid spoke of the geostrategic significance of the Indian Ocean Region and the need to protect and uphold the rule of law. He then elaborated on the Foreign Policy vision of President Ibrahim Mohammad Solih’s Government which seeks to cultivate healthy and mutually beneficial partnerships with all its neighbours and security in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is thus working towards the safety, stability and security of the Indo-Pacific Region and towards ensuring Freedom of Navigation, Maritime Security and addressing the hindrances to that freedom including piracy and organised crime.

Session 1 being addressed by the Cabinet Ministers of six countries.

Session 1

The first Plenary Session of the Conference was addressed by Cabinet Ministers of Seychelles; Mauritius; Bhutan; Nepal; UAE and Timor Leste.

The Designated Minister from Seychelles, Macsuzy Mondon began her address by emphasising on the importance of the blue economy for the states surrounding the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). She outlined the importance of peace and stability in the IOR for its surrounding states. With opportunities come threats, such as piracy, trafficking and terrorism that destabilise the region. Thanking India and the USA for lending support to Seychelles, she called upon the global community for a joint effort to stabilise the region. This could be in the form of multilateral agreements and continued vigilance.

Nandcoomar Bodha, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Regional Integration and International Trade, Mauritius spoke about the significant challenges posed by piracy and terrorism in IOR. A comment was made on the recent freeing of convicted pirates from Somalia’s prisons, a major signal that the threat of piracy remains. With the crucial trade passing through the IOR, it is vital to protect the region against challenges such as trafficking, piracy, smuggling, and terrorism (etc.). The speaker concluded his speech by reiterating the importance of the IOR in being a bridge between Asia and Africa and the need to protect it.

The Minister for Foreign Affairs, Royal Government of Bhutan, Tandi Dorji, began his address by highlighting the cordial and fruitful relationship that Bhutan and the Maldives share. While Bhutan is landlocked, what happens in the IOR does have a significant impact on the nation due to the interconnectedness of the world today. While states face rising sea levels, Bhutan faces threats from melting glaciers that threaten lower-lying regions in the country. The effects of climate change are seen in Bhutan and the need for a concerted global effort is highlighted. To protect trade in the IOR and sustain the benefits of a blue economy, dialogue and collaboration are needed, with such conferences being a necessary first step.

Talking about the theme of the Conference, Pradeep Kumar Gyawali, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Nepal said that Nepal sees this as an apt and critical challenge to address. With relevance in development, biodiversity and vast resources, the ocean is vital for each nation in the region, even Nepal. Climate change is something that also affects Nepal, even though it is landlocked. Further, a multilateral approach is needed to tackle security challenges such as smuggling and trafficking. With the proposed construction of roads and waterways between Nepal and the Indian Ocean, Nepal hopes to have greater involvement in matters about the IOR.

Ahmad Ali Al Sayegh, Minister for Economic Cooperation in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, UAE stated that freedom of navigation and regional cooperation is key to the growth of the ocean, continuing cultural exchanges and continuous trade movement. With the advent of climate change threatening all nations, there is a need to support global dialogues that catalyse climate action. A strong focus on vital issues such as maritime safety and security, cultural exchanges and the blue economy is needed with the help of several countries to continue building bridges and securing the region.

Joaquim Jose Gusmao dos Reis Martines, Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries, Timor Leste discussed the need to engage all partners to great cooperation and responsibility in the region, committing itself to the sustainable development of the blue economy following international law. Through partnership and support, there is a need to address unregulated fishing and developing sea-based tourism in the region, especially in tourism.

Keynote address being delivered by Md Nasheed, Speaker, Peoples’ Majlis, Maldives.

Day 2

Keynote Session II

The Second Keynote Session of the Conference was Chaired by M J Akbar, Member of Parliament, India and Md Nasheed, Speaker, Peoples’ Majlis, Maldives.

M J Akbar, Member of Parliament, India began his talk by diving straight into the history of the ocean. In his address, he stated that with climate change, increased militarisation and globalisation, it is imperative to ensure the safety of the Indian Ocean region. He also stated the importance of the Indo-pacific theatre during WW2, he reiterated the importance of the ocean to global affairs, then and now.

Mohammed Nasheed referenced the history of the IOR, stating the interest of Chinese and later European forces of establishing control over the ocean and their specific interest in surveying the islands of Maldives. While India has maintained a peaceful and strong relationship with the Maldives, he references the issue of land grabs and authoritarian rule in the region as a grave threat. Explicitly stating “I am specifically referring to China,” he outlined land grabs and debt diplomacy that the Chinese have used to gain control of the Maldives. He hopes for a more transparent and mutually beneficial investment in the Maldives from all nations in the region, comparing China to the East India Company. He also discussed the rise of radical Islam that threatens the Maldives and wider region.

Session II

Chair: Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party; Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation

In a special video message, Lisa Curtis, Deputy Assistant to the President, Senior Director for South and Central Asia, National Security Council, USA, highlighted the long term threat from other malign actors who seek to undermine rather than uphold the rules based international order, seek to destabilize the region and reorder it towards their exclusive advantage. She focused on the Indo-Pacific priority of America to realize the goal of strong, sovereign and prosperous nations in the region.

Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Bin Hamood Albusaidi, Secretary-General, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Oman focused his remarks specifically on maritime security in the region, built on the foundations of law and operational security. With piracy being a significant issue in the region, the Minister called for a collaborative effort in policing the sea. Cooperation entails the coordination of naval operations, information sharing and joint training. With trust-building and respect for maritime law, he hopes that states will prioritise long term peace and stability as opposed to short term gain.

Shahriar Alam, Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh stated that Bangladesh, a booming economy, has kept a strong interest and effort in maintaining peace and security in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. With peace and stability in the region, all can take part in prosperous growth. He calls for greater economic integration and coastal shipping agreements to enhance regional connectivity. With “zero-tolerance” to illicit activities in the ocean, he hopes for further strategic partnerships and a security architecture to address the issue. Highlighting the importance of sustainable fishing and the threat of climate change, he called for greater conservation efforts from all nations in the region.

Chhiv Yiseang, Secretary of State, Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation, Kingdom of Cambodia stressed the importance of cooperation in enhancing maritime security in the region, premised on strategic trust among nations. He called for a mutually beneficial framework where the interests of both large and small nations are respected. He outlined the importance of ASEAN in being a forum and “security shell” for its member nations to expand connections. He also stressed the importance of RCEP as being the key economic pillar of the region.

Session III

Chair: Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party; Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation

Kyaw Myo, Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Transport and Communications, Myanmar, stressed the importance of cooperation through bilateral and multilateral settings to address regional issues. With the ever-increasing importance of the region and Myanmar’s strategic location, Myanmar hopes for a greater role on the part of all states in the region. He hopes for the development of “institutionalised cross-regional setting” for integration to tackle marine pollution and terrorism in the region. He stated that Myanmar hopes for peace and harmony in the region and hopes to play a larger role in the future.

Presenting the Japanese perspective, Toshiko Abe, State Minister of Foreign Affairs, Japan, reflected on the strategic importance due to the important sea line of communications. The Indian Ocean region is also the theatre of economic activity for many players. Hence, it faces challenges of both economic and security nature. In the context of the Indian Ocean, the Japanese focus is essentially on three factors, namely, the maritime order, combating piracy and combating terrorism. She focused on the importance of a rule-based free and open order for stability and prosperity.

Ronny Prasetyo Yuliantoro, Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs and Special Advisor to the Foreign Minister on Inter-Institutional Relations, Indonesia stated that he hopes for greater confidence and soft cooperation through dialogue between nations in the region. In a growing economy, ASEAN can play a major role in bringing regional cooperation. The East Asia Summit can further bring economic and maritime cooperation, promoting connectivity and sustainability. With the sustainable development of the blue economy, Indonesia hopes for mutually beneficial growth and prosperity in the region.

Session IV

Chair: Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, India

Ambassador Harry Harris, US Ambassador to South Korea delivering his address.

Harry Harris, the American Ambassador to South Korea and Former Commander of United States Pacific Command, regarded Indian and the Pacific Ocean as the two determinants of the future of the earth. He mentioned the US contribution and the robust manifestation of US to the economic momentum in the region. He highlighted the focus of Trump administration on the creation of strong reciprocal bilateral trade relations that contribute to development through job creations and not debt creation. He advocated for a free and open Indo-Pacific, with states to be strongly independent and be satellites to none in economic, security and governance terms. He also raised concerns over China’s commitment in the region.

Speaking on behalf of the Russian Federation, Yuri Materiy, Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador of Russia to the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka and The Maldives highlighted the Russian interest in the Indian Ocean Region as mentioned in the Maritime Doctrine of 2020. He regarded the Shanghai Cooperation Operation as a potential multilateral dialogue form for concerns in the Indian Ocean with the recent additions in its memberships. He also questioned the substance value of “Indo-Pacific”, while focusing on “Asia-Pacific” as reflective of a constructive partnership and cooperation.

Wei Hongtian, the Ambassador of Department of Boundary and Ocean Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, China, commenced his address by stating the Chinese ambitions to be a strong maritime country based on four principles, namely, peaceful, cooperative, open and win-win development; settlement of maritime dispute through friendly dialogue and negotiation; commitment to maritime cooperation and rules; upholding unobstructed passage and security of international shipping lines. On behalf of China, he proposed a justified reasonable openness of Indian Ocean Region with the participation of all based on negotiations. He regarded BRI to be one such forum for pragmatic cooperation.

Session V

Chair: Shakti Sinha, Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, India

Describing old challenges as common knowledge, Pornpimol Kanchanalak, Adviser to Foreign Minister, Kingdom of Thailand, summarized new challenges to be rooted in the differences between the new great powers and the old international paradigm. She focused on the new Indo-Pacific outlook forwarded by Thailand as the current chair of ASEAN – to move away from confrontation towards constructive cooperation and working together to find some, if not all the solutions with an open mind.

M Shahidul Islam, Secretary-General, BIMSTEC Secretariat, focused his address majorly on the issues in Bay of Bengal and the littoral and adjacent states of BIMSTEC. The Bay of Bengal hosts key transit route between the Indian and the Pacific Ocean, thus becomes crucial in terms of security and strategic concerns of the larger Indian Ocean Region. Recognizing the need for a rule-based order supported by maritime infrastructures, he appreciated the awareness amongst the BIMSTEC states to work closely in developing common perceptions and approach towards them.

Richard Maude, Deputy Secretary, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia addressing the delegates.

Richard Maude, Deputy Secretary, Indo-Pacific Group, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia focused his address on the changing strategic dynamics in the region, the response of region particularly on the regional architecture and contribution of Australia in the region. He highlighted the manifestation of the changing dynamics through the creation of multipolarity in the region; flashpoints in border disputes; and gaining prominence of ‘geo-economics’, where trade, investment and infrastructure are being used not only for connectivity but also to build influence to secure political and economic gains.

Discussing the great strategic importance of the Indian Ocean, Nguyen Van Thao, Assistant to Deputy Prime Minister, Director General of the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vietnam, attributed this importance to connectivity, oil shipment, shipping lanes etc. as factors critical to international trade, navigation and energy security. He concluded his address by bringing into focus the recent activities in the South China Sea and urged the members of Indian Ocean region to stand firm on the rule of law in the oceans and for compliance with UNCLOS and international law.

Session VI

Chair: Vice Admiral Shekhar Sinha, Former C-in-C, Western Naval Command, Indian Navy; Member, Board of Trustees, India Foundation

Detailing the maritime challenges faced by Madagascar and several policy initiatives taken by the country in this regard, Ratsimandao Tahirimiakadaza, Secretary-General, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Madagascar, highlighted the effort required to build maritime oriented development policy. In his address, he reiterated the commitment of Madagascar to contribute in the ongoing international effort to promote a secure and prosperous Indian Ocean region. Supporting the vision of SAGAR forwarded by the India Prime Minister Narendra Modi, he advocated for peace and prosperity in the Indian Ocean region.

Discussing the perspective and experiences from Western Indian Ocean, Michael Kiboino, Director, Oceans and Security, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kenya highlighted the increasing and deliberate prioritization of blue economy as the next frontier of economic growth and development in Africa. He narrowed down three major concerns in realizing the potential of the Indian Ocean for Kenya. These were: land-based root causes of threats contained in passive conflicts and state fragility; the extra-regional dynamics with destabilizing effect in an existing fragile region; and climate change which is defining new security and developmental challenges.

Abdallah Mirghane, Director of the Foreign Minister’s Cabinet, Comoros, in his address stressed on the importance of including the coastal and island states in any dialogue on the Indian Ocean. He highlighted that the economic development of African states is highly dependent on international trade and thus, maritime transport and security are of vital importance. He concluded by emphasising that maritime security must include the elements of international peace, security, sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence.

Session VII

Chair: Vice Admiral Shekhar Sinha, Former C-in-C, Western Naval Command, Indian Navy; Member, Board of Trustees, India Foundation

Edward Ahlgren, OBE, Royal Navy, UK, stated that the Indian Ocean sits at the crossroads of international trade which is a critical link between the world’s powerhouse of Euro-Atlantic and the Indo-Pacific Region. The Indian Ocean is more than a simple transit corridor. The Indian Ocean is contested, congested, and complicated. He concluded by focusing on the need for technological developments to promote security, governance, prosperity and sustainability that we leverage are also available to our adversaries.

Acknowledging that strategic and security environment is highly volatile and ambiguous, Abdulla Shamaal, Chief of Defence Force, Maldives, stated that with complex and interlinked threats &challenges that creates uncertainty for Statesmen and Practitioners, the main cause of this volatility is intense socio-economic as well as military competition among near-peer competitors. He focused on the need for a natural convergence of interests on the part of major regional and international players that fit into India Look East/Act East policy as well as China’s economic network of Belt & Road Initiative and Maritime Silk Route.

Mahesh Singh, Flag Officer Karwar/ Karnataka, Indian Navy, commenced his address by pointing out that the global security environment has changed dramatically over the past few decades. The Indian Ocean is the only connection between the economic prosperity of the West and the aspirations of the East. The statistics of types and numbers of ships that travel through vital shipping lanes of the Indian Ocean Region indicate that they sustain economic activity and enable prosperity across the world. He concluded by stating that today the security of the Indian Ocean Region faces challenges largely from Non-State Actors and in some cases from State-Sponsored Non-State Actors.

5th Dharma Dhamma Conference 2019

Theme: Sat-Chit-Ananda & Nirvana in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions

Dates: 27-28 July 2019

Venue: Rajgir International Convention Centre, Rajgir, Bihar, India

Inauguration Speakers

5th International Dharma Dhamma Conference was organised by India Foundation in collaboration with Nalanda University on 27-28 July 2019 in Rajgir International Convention Centre, Rajgir, Bihar, India. The theme of the Conference was “Sat-Chit-Ananda & Nirvana” in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions. The conference was attended by 250 Scholars from 15 Countries, 37 Distinguished Speakers addressed the Conference while 50 Scholars presented their Research Papers on various sub-themes of the conference.

The Inaugural Session of the 5th International Dharma Dhamma Conference was addressed by Pujya Swami Avdheshanand Giri (Acharya Mahamandleshwar Juna Akhara and Founder, Prabhu Premi Sangh), Shri Kiren Rijiju (Union Minister of State I/C, Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India), Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera (Minister of Buddhasasana and Wayamba Development, Government of Sri Lanka), Lyonpo Sherab Gyaltshen (Minister for Home and Cultural Affairs, The Royal Government of Bhutan) and Prof. Sunaina Singh (Vice-Chancellor, Nalanda University, Rajgir, Bihar).

Pujya Swami AvdheshanandGiri

The conference began with invocations rooted in the Hindu and Buddhist traditions by the students and teachers of Nalanda University. Ms Lalita Kumarmangalam, Director, India Foundation, welcomed all the guests, eminent scholars, academics and students in her welcome remarks in the inaugural session of the conference.

In his Benedictory Address in the Inaugural Session of the conference, Pujya Swami Avdheshanand Giri Ji Maharaj spoke on the spiritual aspect of the theme of the conference. Swami Ji lauded the theme of the conference as very significant and important for the contemporary world. He said that the Hindu traditions conceive the Absolute Truth in terms of three essentials attributes namely Sat, Chit and Ananda. When one knows or experiences these three, then the logical conclusion is the liberation which is Nirvana. He added, “the name of Parmatma in Vedic/Hindu/Sanatana Dharma is Sachidananda and that is the ultimate truth which incorporates all elements of life including the truth, consciousness and Ananda”.

Minister of State (Independent Charge) Youth Affairs & Sports and Minister of State for Minority Affairs, India. MP from the State of Arunachal Pradesh.

The Chief Guest in the Inaugural Session was Shri Kiren Rijiju. He said “Dharma Dhamma Conference is an endeavour to underscore the basic commonality between the two religions – Hinduism and Buddhism. Knowledge culture, which is the Indian Culture, is common among the two religions. The texts of the two traditions have many similarities, though people theorize and practice them differently.”

Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Hon’ble Minister of Buddhasasana and Wayamba Development, Government of Sri Lanka, was the Distinguished Guest of Honor in the Inaugural Session of the Conference. He highlighted that Hindu and Buddhist traditions have to work and live together. He said, “Buddhist teachings are the most relevant to the contemporary world for achieving a sustainable and happy world”.

Lyonpo Sherab Gyaltshen, Hon’ble Minister for Home and Cultural Affairs, The Royal Government of Bhutan, was also the Distinguished Guest of Honor in the Inaugural session of the conference. In his address, he highlighted the natural linkage between Nalanda and Bhutan since time immemorial. He said“the deliberations at the Dharma Dhamma Conference should be focussed on Human mind & Self to develop a compassionate world. Courses and curriculum on self and human mind should be developed to create future citizens who care for happiness and values”.

Sunaina Singh, VC, Nalanda University

In her remarks, Prof Sunaina Singh, Vice-Chancellor of Nalanda University said “Nalanda traditions have been in the true spirit of Sat-Chit-Ananda. The Dharma Dhamma Conference provides a forum for the best minds from the world of academics as well as leading statesmen, policymakers, religious heads from India and abroad to come together to explore new wisdom and meaning in the contemporary world.”

Keynote speakers

The Keynote Session in the Dharma Dhamma Conference was chaired by Prof. S. R. Bhatt, Chairman, Indian Philosophy Congress and Former Chairman, Indian Council of Philosophical Research. The Keynote Addresses in the Session were delivered by Shri Ram Madhav (National General Secretary, Bharatiya Janata Party and Member, Board of Governors, India Foundation), Hon. Mano Ganesan (Minister of National Integration, Official Languages, Social Progress & Hindu Religious Affairs, Government of Sri Lanka), Shrihariprasad Swami (Managing Trustee, Sri Vishnu Mohan Foundation) and Venerable Prof Thich Nhat Tu (Deputy Rector, Vietnam Buddhist University, Vietnam and Founding Member, International Buddhist Confederation).

Shri Ram Madhav, National General Secretary, BharatiyaJanata Party

In his keynote address, Shri Ram Madhav said that “Satchidanand or Moksha is not there to desire or gain, but to experience. This experience begins from the physical world – Isavasyamidam Sarvam – Everything here is Isvara, the divine. Man has to travel from that realisation of the Omnipresent to a state where he becomes the Omnipresent himself, described in Upanishads as Aham Brahmasmi – I am the Creator. From Being to Becoming is the journey. Becoming is Moksha. Upanishads called that becoming as Satchidanand.”

Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Integration, Official Languages, Social Progress & Hindu Religious Affairs, Government of Sri Lanka

Hon. Mano Ganesan, in his Keynote address, underlined the harmony and coexistence of Hinduism and Buddhism since ages and said that Sri Lanka has recognized itself as multi Identity, multiethnic, metalinguistic, multi-religious country just like India.

Shrihariprasad Swami, Managing Trustee, Sri Vishnu Mohan Foundation

Shrihariprasad Swami, in his Keynote address, said: “philosophy and knowledge of the Shastra should transform you otherwise it is of no use”.

Venerable Prof (Dr) Thich Nhat Tu, in his Keynote address, talked about Nirvana which is the Ultimate Goal of Buddhism. He said “the essence of the Buddha’s teachings lies in the four noble truths which are: 1) the statement of what is suffering (dukkha), 2) discovering the cause of suffering (dukkha-samudaya), 3) realisation of the state of the destruction of suffering (dukkha-nirodha) and 4) showing the path leading to that state of destruction of suffering (dukkha-nirodha-gmin-paipad). They form the soteriological structure of the Buddha’s ethical teachings.

Venerable Prof (Dr) ThichNhatTu, Deputy Rector, Vietnam Buddhist University, Vietnam and Founding Member, International Buddhist Confederation

There were four Plenary Sessions in the conference where 27 Distinguished Speakers from various countries addressed the conference on four sub-themes of the conference namely Sat, Chit, Ananda and Nirvana. The first Plenary Session in the conference had discussions on the Sub-theme Sat (Truth) in Dharma Dhamma Traditions. The second Plenary Session had discussions on Sub-theme Chit (Consciousness)while the third Plenary Session discussed Ananda (Bliss) Sub-theme and fourth and final Plenary Session had an engaging discussion on Nirvana (Enlightenment) in Dharma Dhamma Traditions. There were also 8 parallel Sessions in the Conference where Scholars presented their Papers on Sub-themes of the Conference.

GULF IMBROGLIO: – CHANGING GE-OIL-ITICS

The present time is colloquially being called the Asian Century for all the right reasons. If the 19th century was Britain’s Imperial century and the 20th was American, then the 21st century is becoming the Asian century. By 2020, the economic growth (in purchasing power parity terms) of Asian giants put together will surpass the rest of the world and that is likely to be the future trend as well.

The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has played and continues to play a vital role in creating this Asian prosperity through the “road of development in the twenty-first century.” Today, the Indian Ocean has become a major conduit of international trade as it was until a few centuries back. While occupying almost 20 per cent of the earth’s surface, the IOR is inhabited by 35 per cent of the world’s population staying in 38 littoral states. Over 100,000 ships transit through the Indian Ocean every year, accounting for 66 per cent of the world’s oil cargo, 50 per cent of container cargo and 33 per cent of bulk cargo.[1] India’s 90 per cent trade by volume and 70 per cent trade by value is dependent on the Indian Ocean. The major fuel for growth for most of the Asian countries is oil. For the Asian countries, the supply of oil comes from West Asia—the Gulf region—while the major consumers, India, ASEAN, China, South Korea and Japan lie to the East. This oil, which fuels the growth of Asia is transported eastward from the Gulf via the Indian Ocean. The security of the production centres, as well as its transportation across the sea lanes, is thus vital for Asia and any disruption could put a huge question mark on the emergence of the 21st century as the Asian century. Oil thus is the most important governing factor of geopolitics these days andowing to its criticality the word “ge-oil-itics” needs to be introduced into common strategic parlance.

Asian economies have grown to be heavily dependent on oil imports to satisfy their growing demand. Crucially, Asian economies purchase most of this oil from the Gulf. As a share of oil imports, the Gulf region accounted for 44% of oil imports for China, 63.6% for India, 86% for Japan and 77.1% for South Koreaaccording to 2017 data compiled by the Observatory of Economic Complexity. Off late, some incidents impacting on oil security have exposed the vulnerability of Asian powers to events occurring in the Gulf. The mine attack, which blew of the hull of a Japanese oil tanker at a UAE port and 30 Indian sailors being detained by Iran who were on board a British tanker which was carrying the flag of Panama are cases in point.[2] But of even greater concern is the attack which took place on Saudi oil facilities on 14 September 2019. This attack has not received the attention it deserves, but if oil facilities continue to be targeted in the Gulf, the Asian century is unlikely to materialise any time soon.