The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is home to a diverse population with unique socio-economic and physical characteristics. This region is particularly vulnerable to climate change, and addressing its multi-dimensional impacts across the pillars of peace and prosperity is imperative. Recently, the region experienced natural calamities such as Cyclone Idai and Cyclone Kenneth that struck Mozambique, Malawi, and Zimbabwe, resulting in the loss of over 1,000 lives, widespread infrastructure damage, and crop destruction. Similarly, India suffered from one of the worst heatwaves in its history in 20XX, resulting in several hundred deaths and significant damage to crops and the agricultural economy. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as the Maldives, Seychelles, and Mauritius are particularly vulnerable to climate change because of their low-lying coastal areas and heavy reliance on climate-sensitive sectors like tourism and fishing.

There is an urgent need for investments in climate-resilient infrastructure and sustainable land-use initiatives facilitated through multi-sector collaborations to build resilience. Additionally, there is a need to think more holistically about economy-wide climate transitions in the face of increasing transitional risks. For instance, global responses to climate change commitments on trade and commerce on a global level, such as Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism introduced by the EU in December 2022, are set to impact IOR economies such as India, Maldives, and Bangladesh, whose exports heavily rely on industries that highly carbon-dependent for their input processes.

A climate-ready financial sector is crucial to these efforts; the annual cost of adaptation will likely range between USD 140-300 bn by 20301. Investing in adaptation efforts that have mitigation co-benefits can help improve the efficacy of climate finance, most of which will be directed through the financial sector. As a crucial intermediary, the sector is well-placed to address the needs of various stakeholder groups vulnerable to the impacts of climate change to foster a collective transition to a climate-smart economy. Furthermore, governments of the IOR need to introduce climate-focused policies and regulations to enable this transition. They can also encourage innovation and climate-focused start-ups to support this transition, allowing the financial sector to invest in sustainable projects.

Impacts of Climate Change on the Indian Ocean Region

Climate change has accelerated in the region. The global mean temperature in 2022 was 1.15 degrees Celsius higher than the pre-industrial average, and the eight years from 2015-22 were the warmest ever recorded.2 The Indian Ocean has warmed by ~ 1°C since pre-industrial times and is projected to continue warming resulting in coral bleaching, ocean acidification, and changes in marine ecosystems. This is accompanied by rising sea levels in the Indian Ocean (an average of 3.3 mm per year since 1950), an increase in the intensity and frequency of tropical cyclones (which could increase by 10 times in some IOR countries by 2100), and an increase in the risk of droughts and water scarcity, perturbated by changing monsoon patterns.

These pose significant challenges to the region’s economies and human well-being by damaging property and infrastructure, worsening food insecurity, increasing inequality and poverty, and reducing labour productivity. For instance, the rising sea levels could display up to 13 million people in the IOR by 2100 and could cause economic losses of up to USD 1.7 trillion.3 Under such circumstances, climate-stress-induced mass migration and conflicts arising from competition in accessing the dwindling natural resource base are projected to increase further.

These vulnerabilities are not evenly distributed but are differential based on geography and socioeconomic conditions. For instance, island nations and poor economies are more vulnerable due to a lack of effective means to mitigate the effects. These vulnerabilities are enhanced for indigenous communities in the IOR as their livelihoods and cultural practices are closely tied to the health of natural resources. Furthermore, across these groups, the social impacts of climate change disproportionately affect women and girls, who often have limited access to resources and agency to adapt to changing conditions. Hence, it is crucial to take a nuanced understanding of how climate change impacts differ across regions and populations to develop inclusive and equitable adaptation pathways.

In regions where the dependence on natural ecosystems to meet livelihood needs is high, changing climate and weather extremes have implications for peace and security. Decreasing crop yields that threaten famine, or the anticipated loss of landmass in coastal areas, introduce competition in existing patterns of resource consumption across communities, economic sectors, and geopolitical boundaries, sometimes leading to violence and political instability. IPCC AR6 has asserted with high confidence that climate extremes increasingly drive displacement in all regions, with SIDS disproportionately affected.4 Climate change has generated and perpetuated existing vulnerabilities through displacement and involuntary migration. At progressive levels of warming, involuntary migration from regions with high exposure and low adaptive capacity is set to occur more frequently. In response, the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) has made responding to climate-related security risks one of its strategic priorities for 2020-22, with this agenda gaining broader recognition in global narratives and diplomatic dialogues. Regional dialogues and country-level responses to the impacts of climate-induced resource competition and migration on national/regional peace and security need to build on collaborative governance and participatory sustainable resource management practices, emphasizing cross-collaborations across the regional actors and key sectoral players.

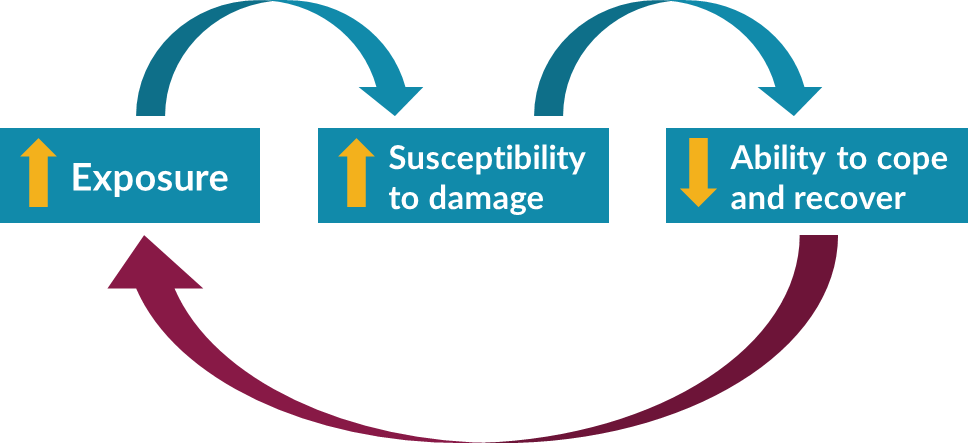

Economic growth rate and pattern are critical elements in raising prosperity levels and reducing societal inequalities, and climate change has a decisive bearing on both. The impact of climate change in the IOR is expected to have significant costs to the economy. A study by the Asian Development Bank suggests that the costs in South Asian countries will reach up to USD 215 billion per year by 2050.5 For some countries, this would result in a ~12% loss in their per capita GDP by the end of this century.6 Climate change also impacts human health, including increased incidence of heat stress, water-borne diseases, and vector-borne diseases such as dengue fever and malaria, in addition to food security. The effects of this are notably worse for the disadvantaged groups, whose needs are traditionally underserved and whose perspectives are often underrepresented in climate negotiation spaces. These groups get caught up in a vicious cycle of being increasingly affected by future climate extreme events. Their increasing inability to cope with the rising risks increases their exposure further (Figure 1). Lifting vulnerable communities out of this vicious cycle while meeting the countries’ climate commitments would require transformations in the economic sector, with coordinated efforts by stakeholders across the ecosystem. This would set us on the path of becoming a decarbonized economy that supports people’s financial well-being while promoting climate resilience.

Figure 1. Viscous cycle affecting the prosperity of vulnerable populations

Source: Adapted from Islam and Winkel, 2017. Climate Change and Social Inequality. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Working Paper No. 152.

Towards a decarbonized economy

Addressing the impacts of climate change on peace and prosperity would require a radical shift in how the economies of the region function. While meeting NDCs is a crucial first step in addressing its impacts (Table 1), a more significant shift at a systems level is needed to ensure that the economic sector is better equipped to deal with the physical and transitional risks that come with moving toward a decarbonized economy. Physical risks in this context refer to the direct impacts of climate change, such as natural disasters, extreme weather events, and sea-level rise in the IOR region. These can have immediate and direct effects on economic activities, including damage to infrastructure and property, disruptions to supply chains and markets, and increased insurance and financing costs for resilience. Transitional risks refer to the indirect impacts of climate change on the economy, such as policy changes, technological innovations, and shifting consumer behaviours and purchase patterns. These can have long-term implications for economic activities, including changes in market demand, regulatory policies, and investor preferences. Additionally, regulatory guidelines such as carbon pricing or trade regulations can have implications for industries’ competitiveness and profitability. Hence, this radical shift needs to be reflected in how the financial and broader economic sectors internalize climate change’s impacts across their value chains.

| S.No | Country | NDC Target | Estimated CO2e reduction (million tonnes) | Additional Information |

| 1 | Australia | Reduce emissions by 26-28% below BAU by 2030 | 245-260 | – |

| 2 | Bangladesh | Reduce emissions intensity by 5% from 2010 levels by 2030 | 90 | – |

| 3 | Comoros | Reduce emissions by 29.4% below BAU by 2030 | 0.5 | – |

| 4 | France | Reduce emissions by 40% below BAU by 2030 | 63 | – |

| 5 | India | Reduce emissions intensity by 33-35% from 2005 levels by 2030 | 3,042 | – |

| 6 | Indonesia | Reduce emissions by 29% below BAU by 2030 | 2,107 | Includes conditional target of up to 41% emissions reduction with international assistance |

| 7 | Iran | Reduce emissions intensity by 4% from 2010 levels by 2030 | 109 | Conditional target subject to international support |

| 8 | Kenya | Reduce emissions by 30% below BAU by 2030 | 138 | – |

| 9 | Madagascar | Reduce emissions by 14% below BAU by 2030 | 3.3 | – |

| 10 | Malaysia | Reduce emissions intensity of GDP by 45% from 2005 levels by 2030 | 297 | – |

| 11 | Maldives | Reduce emissions by 10% below BAU by 2030 | 0.1 | – |

| 12 | Mauritius | Reduce emissions by 30% below BAU by 2030 | 0.8 | – |

| 13 | Mozambique | Reduce emissions by 30% below BAU by 2030 | 47 | – |

| 14 | Oman | Reduce emissions intensity by 2% from 2016 levels by 2030 | 26 | Conditional target subject to international support |

| 15 | Seychelles | Reduce emissions by 29% below BAU by 2030 | 0.1 | – |

| 16 | Singapore | Reduce emissions by 36% below BAU by 2030 | 19 | – |

| 17 | Somalia | Reduce emissions by 7% below BAU by 2030 | 1.1 | Conditional target subject to international support |

| 18 | South Africa | Reduce emissions by 28% by 2030 and by 42% by 2025, relative to BAU | 427 | South Africa’s NDC includes both unconditional and conditional targets subject to international support |

| 19 | Sri Lanka | Reduce emissions by 4% below BAU by 2030 | 5.5 | – |

| 20 | Tanzania | Reduce emissions by 10-20% below BAU by 2030 | 62 | – |

| 21 | Thailand | Reduce emissions by 20-25% below BAU by 2030 | 308 | – |

| 22 | United Arab Emirates | Reduce emissions intensity by 23.5% from 2016 levels by 2030 | 196 | – |

Table 1. Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of IOR countries

MANAGING PHYSICAL RISKS: THE CASE FOR CLIMATE-RESILIENT DEVELOPMENT

Efforts to mitigate the physical risks that come with climate change need to double down on actions that focus on building the adaptive capacity of systems to respond to its impacts, including building resilient infrastructure, taking disaster risk-reduction measures, increasing sustainable practices across industrial supply chains, etc. This, among other societal benefits, would also result in reduced economic costs of recovery in the face of future extreme events. There is a growing recognition that climate financing in the global south needs to go beyond the energy sector’s green transition and catalyze funding for adaptation efforts with mitigation co-benefits. According to UNEP, the annual costs of adapting to climate change by 2030 might require thrice the quantum of existing funding levels, a significant share of which comes from the state. To address this gap, there is a need for scaling private sector participation through innovative, blended financing models. These models would ensure that various actual and perceived financial risks that come with climate adaptation finance are appropriately distributed among diverse economic actors based on their capabilities and appetite for risks. Increased funding levels in this regard should focus on land-use transitions that emphasize improving the services provided by natural capital while ensuring that the adaptive capacity of human-nature systems is enhanced in the process. There is an opportunity to build on the momentum enabled by global efforts to scale finance and action toward adaptation to focus on transitional changes at a systems level versus incremental steps that are uncoordinated and planned to increase short- and mid-term gains, often resulting in maladaptation.

MANAGING TRANSITIONAL RISKS: CLIMATE-SMART TRANSITIONING OF THE FINANCIAL SECTOR

In June 2019, the IMF endorsed investing in resilience building by disaster-prone nations, citing improved economic performance over the mid and long term. OECF estimates that the global investment requirements for addressing climate change will be to the tune of trillions of USD, with investments in resilient infrastructure alone requiring USD 6 trillion annually up until 2030. Most of these flows will be mediated through financial institutions. They are essential in complementing and potentially amplifying climate policy action by accelerating investments toward a low-carbon economy. Setting the right stage for the financial sector to play a crucial role in this capacity would require introducing mechanisms and processes to lower the transitional costs of becoming climate smart. While financial institutions already provide insurance and other risk-sharing instruments, they can play an even more fundamental role by supporting reforms across three key areas: governance, risk identification management, and disclosures of climate risks. Some leading central banks, such as the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, are already implementing these changes. For instance, the Bank of England was the first central bank to set supervisory expectations in 2021. In addition to setting up a climate financial risk forum, it has published risk management guidelines and conducted stress rest on its portfolio. In 2022, they published an online scenario analysis tool that any FI can use to evaluate its portfolio against climate risks.

While the central banks of countries in IOR are progressing in their thinking in enabling such a transition, implementation of the same remains nascent. For instance, the Reserve Bank of India, ranked 12th among G20 central banks for green policies and initiatives, created a sustainable finance group in 2021 and announced its scenario analysis and disclosure framework in 2023. It is presently engaged in developing implementation mechanisms to underpin the transition. There is a need for channels of learning and collaborations across the IOR regions that can leverage existing efforts and best practices to advance action on this agenda, thereby improving the economies’ resilience to climate change. However, this transition as a stand-alone effort would not be effective if the rest of the economic sector is not ready to absorb the implications of these changes on their functioning. Preparing the financial sector for such a transition is particularly crucial for SIDS in IOR, whose major contributing industries stand to lose the most owing to their dependence on and vulnerability to changes in the natural capital.

ENABLING A SECTORAL SHIFT: MAKING ECONOMIES CLIMATE-COMPETITIVE

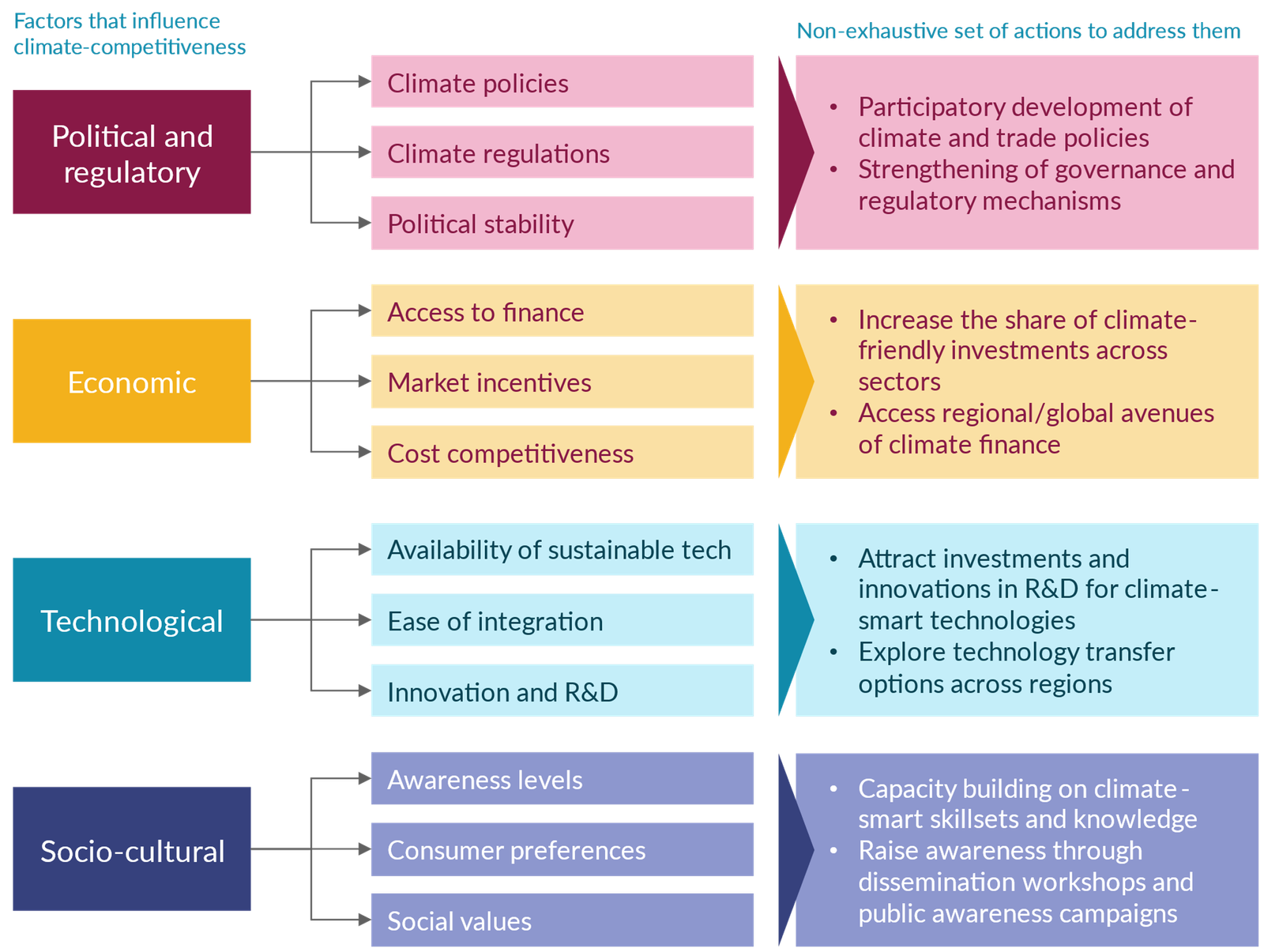

In December 2022, the European Union unveiled its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms to advance its vision of achieving carbon neutrality in the European industrial sector by 2050. Several countries in the IOR, such as India, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh (refer to case study), rely heavily on carbon-based industries for their global trade and commerce. Not responding to these policy shifts would increase increased costs of international trade, thereby affecting their economies. Therefore, there is a need for industries contributing to major exports to explore ways of reducing their carbon footprint and becoming more climate-competitive in the global markets. Efforts to decarbonize the significant contributing sectors are an opportunity to make the economies climate-

competitive and meaningfully contribute to resilience-building in the region. These efforts must be coordinated through a systemic approach to address the various factors, namely, political and regulatory, economic, technological, and socio-cultural, that influence the sectors’ functions and responsibilities. Having a framework that could aid in evaluating countries’ readiness and evolving appropriate interventions across the four factors could help inform targets and pathways of change needed to make the economic sector climate-competitive (Figure 2). This needs to be underlined by solid cooperation and strategic partnerships across various stakeholders, both affecting and affected by the economic sector, nationally and regionally.

Figure 2. Framework to inform country-level climate competitiveness of the economic sector

Progressing Partnerships toward climate resilience in Indian Ocean Region

Climate change affects everyone, everywhere, all at once. Hence, the wide range of stakeholders involved in climate action must come together in negotiating for climate-resilient pathways for the future. Multi-sectoral cross-collaborations involving decision-makers and communities affected through highly participatory forums are needed to bring about an equitable and just transition toward an IOR that promotes peace and prosperity in the process of becoming climate smart. Collaborations across regions need to go beyond the conventional North-South partnerships to include more associations and collectives led by countries of the global south. This would mean inter-regional cooperation across the length and breadth of the ecosystem actors in IOR for financial support, technology development and transfer, infrastructure development, institutional building, and collaborative learning. The United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC) recognizes the importance of Southern partnerships on climate change issues as valuable means of sharing their experiences and learning from each other based on mutual trust, collaboration, and understanding based on local contexts and consciously avoiding the traditional donor-recipient relationships.7 The existence of several partnerships in the IOR context, including the Indian Ocean Rim Association, Indian Ocean Commission, Partnerships for Resilience, and Indian Ocean Dialogue, needs to be leveraged to progress climate partnerships in the region. Ensuring that the recommendations from these partnerships accommodate the needs of downstream actors across the ecosystem is crucial to building just future pathways of impact. Apart from proactively facilitating and participating in these partnerships, the state has an important role to play in setting ambitious targets, providing policy support and guidance, introducing effective regulatory mechanisms, and encouraging innovation through accelerators and incubators that will set the stage for IOR’s transition into a cluster of decarbonized economies. This needs to be complemented by efforts of the private sector to catalyze more funding, advocate for increased uptake of sustainable practices across the economic sector’s value chains, and seed innovations in climate technologies.

INDIA’S APPROACH TO CLIMATE PARTNERSHIPS: INTERNATIONAL SOLAR ALLIANCE AND COALITION FOR DISASTER RESILIENT INFRASTRUCTURE

India has been instrumental in developing key partnerships to advance climate action on a global scale.

The International Solar Alliance (ISA) is an international organization launched by India and France during COP21 in 2015 with the primary objective of promoting the use of solar energy worldwide by driving market adoption for solar technologies in developing countries. At present, 110 countries are signatories to the ISA Framework Agreement. In 2020, it launched ISA Affordability Solar Project to provide 1000 MW of solar energy to the least developed and small island developing states by 2030. It has also established the ISA Innovation and Investment Cell to mobilize more than USD 1 trillion in solar investments by 2030. As the host country of ISA, India has committed to providing a grant of USD 27 million. It has established a dedicated ISA cell at the Ministry of External Affairs to coordinate India’s efforts.

The Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI) is a global partnership of countries, organizations, and other stakeholders committed to promoting infrastructure resilience to climate change’s impacts. It was launched at the UN Climate Action Summit in 2019 to bring together knowledge, expertise, and financial resources to support the development of sustainable infrastructure worldwide. CDRI has launched a project on ‘Mainstreaming Disaster Resilience in Infrastructure Investments’ in partnership with the Global Infrastructure Basel (GIV) Foundation with the aim of developing a framework for integrating disaster risk management into infrastructure investments. Since its inception, it has collaborated with multilateral development banks, such as World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the European Investment Bank, to mobilize financial resources for disaster-resilience infrastructure in the CDRI member countries. India has committed to providing USD 10 million to CDRI’s corpus fund and has established a CDRI secretariat in New Delhi to coordinate its efforts.

These partnerships reflect the country’s commitment to promoting global climate action towards resilience-building and fostering international cooperation in addressing the impacts of climate change at scale.

Conclusions

The vulnerability of countries of IOR to climate change is multi-dimensional, and their impacts on their socio-economic security are inherently complex owing to their diversity. Its high reliance on natural ecosystem processes to meet its social and economic needs has crucial implications for the region’s peace and prosperity in the face of climate change. Climate action in IOR needs to prioritize climate adaptation efforts that have mitigation co-benefits while also focusing on building the capacity of social-economic systems to adapt to the anticipated changes.

The financial sector has a key role to play in this transition as most of the regional, national, and international climate finance needed to bridge the huge funding gap will be mediated through it. A climate-smart financial sector is hence crucial in amplifying climate action. It also has a direct implication for how natural capital is valued, managed, and governed. Making the financial sector climate-smart would require developing policies and regulatory policies that can effectively mitigate the physical and transitional risks that come with the transition. Further, the global shift towards becoming decarbonized economies has led to the introduction of several climate policies and regulations, such as EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. These instruments have a bearing on the economies of IOR countries that are highly reliant on carbon-intensive industries for their exports as they reduce their climate competitiveness. Hence the financial sector’s transition into becoming climate-smart must be complemented by efforts to decarbonize the economic sector overall, thereby contributing to climate-smart social-economic growth while making the economies climate-competitive.

As climate change affects all, multi-sectoral cross-collaborative partnerships across the region, among various stakeholder groups, in key areas, including financial support, technology transfer, climate-smart innovations, capacity building, and collaborative learning, are key to charting a common vision and shared pathways for a resilient future. With strategic partnerships, IOR economies can become climate-smart and support a prosperous, harmonious, and climate-resilient future.

Authors Brief Bio: Anirudh Kishore is Associate Consultant, Dalberg Advisors and Jagjeet Singh Sareen is Principal, Dalberg Advisors.

Note: This article was published by India Foundation in the Indian Ocean Conference 2023 Theme Paper Booklet.

References:

- Asian Development Bank. “Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Asia”, Asian Development Bank, 2017.

- Auffhammer, M. “The (Economic) Impacts of Climate Change: Some Implications for Asian Economies”. ADBI Working Paper 1051, 2019.

- IPCC, 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- United Nations Development Programme, 2021. Addressing the Climate Crisis in the Indian Ocean Region.

- United Nations Environment Programme, 2021. Adaptation Gap Report 2020.

- United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation, 2017. Climate Partnerships for a Sustainable Future Report: An overview of South-South cooperation on Climate Change in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.

- World Meteorological Organization, 2022. WMO Provisional State of the Global Climate.