On 26 July 2019, the Indian nation, but more particularly the great Indian Army will commemorate the 20thanniversary of “Operation Vijay”, the code name of Kargil operations with the theme ‘Remember, Rejoice and Renew.’ Troops from three battalions will undertake expeditions to the peaks where their units had fought under impossible conditions (15000 to 18000 feet high peaks) to drive out Pakistani intruders. “We ‘remember’ our fallen heroes by revisiting their sacrifices which instils pride and respect. We ‘rejoice’ by celebrating the victory in Kargil and we ‘renew’ our resolve to safeguard the honour of the tricolour, an Army official said on the theme of this year’s celebration.

Pakistan’s Kargil adventure codenamed “Operation Badr” was planned in good time which included the construction of logistical supply routes. On more than one occasion, the army had given past Pakistani leaders (Zia ul Haq and Benazir Bhutto) similar proposals for infiltration in the Kargil region in the 1980s and 1990s, says General (Rtd) V.P Malik, the then Indian army chief. However, the plans had been shelved for fear of drawing the nation into all-out war. Some analysts believe that the blueprint of attack was reactivated when Pervez Musharraf was appointed aschief of army staff in October 1998.

In a disclosure Nawaz Sharif, the then Prime Minister of Pakistan stated that he was unaware of the preparation of the intrusion, and it was an urgent phone call from Atal Bihari Vajpayee, his counterpart in India, that informed him about the situation. Responding to this, Musharraf asserted that the Prime Minister had been briefed on the Kargil operation 15 days ahead of Vajpayee’s journey to Lahore on February 20. Sharif had attributed the plan to Musharraf and “just two or three of his cronies”, a view shared by some Pakistani writers who have stated that only four generals, including Musharraf, knew of the plan.

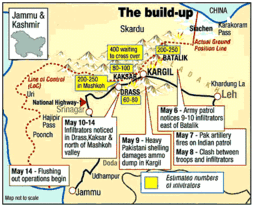

In early May 1999, the Pakistan Army moved to occupy the Kargil posts, numbering around 130, and thus control the area and the highway linking Ladakh with the rest of the country. It deployed the elite Special Services Group as well as four to seven battalions of the Northern Light Infantry (a paramilitary regiment not part of the regular Pakistani army at that time) backed by the jihadists from PoK and Punjab and Afghan mercenaries. Covertly or overtly, they set up bases on the vantage points of the Indian-controlled region.

Pakistan had opened heavy artillery fire across the Line of Control to provide cover for the infiltrators. A shepherd from Garkhon village, Tashi Namgyal, had first spotted the intruders at Jubar ridgeline in Batalik on May 3, 1999, and alerted the Army. He, along with two of his friends, had gone looking for a lost yak. While peering through his binoculars, he saw six Pakistani soldiers dressed in black Pathani outfits

Our army brought in about 250 artillery guns to clear the infiltrators in the posts that were in the line of sight. The Bofors field howitzer played a vital role and the IAF used laser-guided bombs to destroy well-entrenched positions of the Pakistani forces. It is estimated that in the war, nearly 700 intruders were killed by air action alone.

The Indian Navy also readied itself for an attempted blockade of Pakistani ports primarily Karachi port. Later on, Prime Minister of Pakistan Nawaz Sharif disclosed that Pakistan was left with just six days of fuel to sustain itself if a full-fledged war had broken out. As Pakistan found itself entwined in a tricky position, the army had covertly planned a nuclear strike on India. The US President, Bill Clinton issued a stern warning to Nawaz Sharif. Two months into the conflict, an estimated 75%–80% of the intruded area and nearly all high ground was back under Indian control.

Following the Washington Accord on July 4, where Sharif agreed to withdraw the Pakistani troops, most of the fighting came to a gradual halt. In spite of this, some of the militants still holed up did not wish to retreat, and the United Jihad Council (an umbrella for all extremist groups) rejected Pakistan’s plan for a climb-down, instead deciding to fight on. Following this, the Indian army launched its final attacks in the last week of July; as soon as the last of these Jihadists in the Drass subsector had been cleared, the fighting ceased on July 26. The day has since been marked as Kargil Vijay Diwas (Victory Day) in India. By the end of the war, India had resumed control of all territory south and east of the Line of Control, as was established in July 1972 as per the Shimla Accord.

The unparalleled bravery and fighting spirit exhibited by the Indian soldiers and officers can be gathered from the contents of the following paragraph from a PTI reportage; “ A treacherous ridgeline in the Batalik sector, Khalubar saw a major battle with 1/11 Gorkha Rifles leading the fight. Lt Manoj Kumar Pandey led the final assault and was awarded the country’s highest gallantry award Param Vir Chakra. The terrain of Batalik-Yaldor-Chorbatla sector is the most rugged after the Siachen Glacier, with heights ranging from 15,000 feet to 19,000 feet. The temperatures in winter range from minus 10-15 degrees Celsius on a sunny day to minus 35-40 degrees Celsius at night. Even in summer, the night temperatures hover around minus 5-10 degrees Celsius. In the heights of Kargil, The signs of the battles may have long obliterated, but the locals still vividly recall the Indian Army’s bravery. “We are proud of our Army which fought a deadly short war in these rugged, remote and inhospitable sectors and reclaimed all our posts,” a resident of Garkhon village in Batalik sector, TseringDolkar, told PTI”

Pakistan’s perspective

Pakistan’s first perspective of its Kargil misadventure in which a large number of her troops especially those of the Northern Light Infantry were killed besides many irregulars, isthat while there is broad consensus that Kargil-like operations are not viable in the current international environment, violence in various forms remains a legitimate—if not the only—means to achieve Pakistan’s political objectives in Kashmir. Pakistan understands it paid heavily for its adventurism and the international community did not support the use of overt force to alter the status quo. Thus Islamabad has concluded that the use of Pakistani troops in Kargil invited political failure, and consequently, its incentive to repeat such an operation is verymeager.

The second perspective is that in the calculus of Pakistani Generals, their Kargil strategy of total secrecy of this conspiracy has succeeded in keeping the Pakistani state and the nation both in complete darkness about the ground reality of Kargil war. Pakistanis believe and so do their Kashmiri henchmen that Kargil war was part of Pakistan-sponsored so-called freedom movement in Kashmir.

The third perspective isthat Kargil-like operations are disavowed, but violence remains a legitimate tool to achieve political objectives. Given these constraints, Pakistan believes that one of its few remaining successful strategies is to “calibrate” the heat of the insurgency in Kashmir and possibly pressure India through the expansion of violence in other portions of India’s territory. Security managers and analysts widely concur that Pakistan will continue to support the insurgency in Kashmir, and some have suggested it could extend such operations to other parts of India. Incidentally, notice has to be taken of the recent statement of an ISIS operative that they have established twocentres of operation, one in South Kashmir and the other in Pakistan. A few days before the Ansar Ghazavatul Hind commander Zakir Musa was gunned down in South Kashmir he had said in a statement that they were fighting neither for the “Azadi” of Kashmir nor for Pakistan but for the Islamic Caliphate for which Kashmir was central.

The third and the most dangerous take of Pakistan from Kargil war is that ultimately not able to face India in a conventional war, Pakistan must not turn down the option of using the WMD. She has developed tactical local delivery of the dirty bomb. As we have seen in this paper, at one point of time in the Kargil war, Pakistan was thinking of using the WMD. US President Bill Clinton summoned andwarned the Pakistani Prime Minister.

While we are remembering and paying homage to our martyred soldiers on the Kargil Divas and are fondly acknowledging the sacrifices of our armed forces, we also need to remind our leaders and policy planners what take Pakistan has taken from the Kargil war and how the enemy is changing strategy of befriending inimical elements within our people for their nefarious designs. Kargil success should not make us complacent nor should we underestimate the known and unknown the Jaichands in our society.

(Prof. K.N. Pandita is the former Director of the Centre of Central Asian Studies, Kashmir University, Srinagar. Views expressed are personal.)