There is a famous quote among Arab scholars. It is said that when the Umayyad Dynasty fell, they asked Abbasid Caliphate Abu Ja’far Al Mansur about the reasons for its demise, and this wise man cried out, “We handed over the small matters to adults and the big matters to the children, so we divided them between excess and negligence. Rather, he added with regret: We brought the enemy closer, hoping to gain his affection, and pushed the friend away, guaranteeing his loyalty. So, we suffered the treachery of the first and lost the loyalty of the second.”

However, many factors contributed to the fall of the Umayyad Dynasty. Its weakening started with the defeat of the Syrian army by the Byzantine emperor Leo III in 717 CE. Many other contributory factors, like the division among the rulers, intertribal feuds, economic factors, and the high rise of prices, besides the plague inflicted on the state, led to migration and the disintegration of the dynasty. The Abbasid dynasty defeated the Umayyad dynasty with the help of non-Arab Muslims and lasted from 750–1217 until the Ottomans took over.[1]

Nothing has changed from then to date, and the saga of Arab suffering continues. What is it like today compared to yesterday?

The transformation of the Arab nation from a sense of unity and solidarity to a fragmented collection of states is a significant aspect of modern Middle Eastern history. The concept of an “Arab nation” historically evoked a sense of shared identity, culture, and heritage among the region’s peoples. The centuries-long Ottoman rule over the Arab world is depicted as a period of stagnation and suppression of intellectual and scientific progress. The Ottoman Empire’s policies restricted the role of intellectuals, scientists, and progressive leaders, denying them opportunities for advancement and contribution to society.

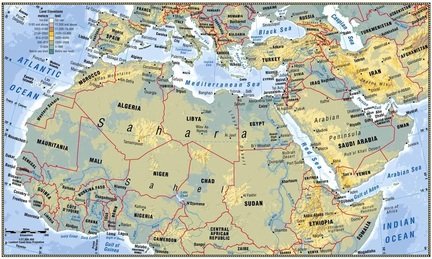

The colonial legacy and the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, named after the British and French diplomats who negotiated it, divided the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) into spheres of influence between the two colonial powers, disregarding local aspirations and identities. The content of the declaration seems no less distant or downright baffling. The prominent Jewish intellectual Arthur Koestler, repeating a frequent mantra, would call it “one of the most improbable political documents of all time,” in which “one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third.[2]

This betrayal of Arab leaders, who were promised independence in exchange for their support against the Ottomans, underscores the manipulative tactics of colonial powers in the region. This agreement, along with other colonial interventions in the region, laid the foundation for the modern nation-states in the Middle East, often drawing arbitrary borders that did not correspond to the ethnic or religious demographics of the region.[3]

The role of external powers, such as Britain, France, and later the United States, in shaping the political and economic landscape of the Middle East cannot be overstated. From colonial rule to interventionist policies, these powers have exerted significant influence over the region, often to further their strategic interests, leading to instability, conflict, and the suppression of indigenous movements for self-determination. The “birth of a ‘Jewish State’ in the heart of Palestine by Britain” alludes to the Balfour Declaration of 1917 in which the British government expressed support for the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. This declaration, coupled with subsequent British policies and the United Nations partition plan in 1947, led to the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, a development that has had profound consequences for the region, including ongoing conflict and displacement of Palestinian populations. The ongoing Israel war on Palestine is but a manifestation of the old policy, which will impact US and European Union influence in the region.

The transition from a unified Arab nation to a fragmented collection of states, shaped by colonial legacies and external interventions, remains a defining feature of modern Middle Eastern history, influencing regional dynamics and conflicts today. The struggle for control over the Arab world has been influenced by its rich natural resources, strategic geographical location, and historical significance as a crossroads between East and West. The Arab world is endowed with vast reserves of oil, natural gas, and other valuable resources. These resources have made the region a focal point for international competition and have attracted the interest of colonial powers seeking to exploit them for economic gain. Control over these resources has been critical to shaping the region’s geopolitical dynamics. The Arab world’s geographical location between Europe, Africa, and Asia has endowed it with strategic importance throughout history. Its position as a natural corridor between three continents has made it a crucial hub for trade, transportation, and military access. This has made the region a target for colonial powers seeking to control key trade routes and military chokepoints.

Colonial European powers, driven by economic interests and geopolitical ambitions, sought to maintain control over the Arab world by ensuring its fragmentation and division. By fostering internal divisions, supporting authoritarian regimes, and drawing arbitrary borders, colonial powers sought to keep the region weak and easily exploitable for their benefit. The United States, inheriting the legacy of colonial powers in the region, became a dominant player in the Arab world following World War II. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US emerged as the world’s sole superpower, further consolidating its influence over global affairs, including in the Middle East. American foreign policy in the region has often been driven by strategic and economic interests, mainly energy and Israel-centric, leading to interventions, support for friendly regimes, and efforts to maintain stability to ensure access to vital resources and ensure Israel’s dominance in the fragmented region. Israel’s expansionist policies, particularly regarding its treatment of the Palestinian-occupied territories, have long been a source of contention in the region. The Israeli government’s determination to achieve its objectives and its ongoing conflict with Palestinian groups exacerbate tensions and fuel instability, with potential repercussions for regional security and stability for years to come.

The future world order will likely be influenced by a combination of ongoing geopolitical trends and emerging challenges, particularly in West Asia.

The invasion of Iraq and subsequent events, such as the Arab Spring, have contributed to the destabilisation and fragmentation of modern Arab states. These events have led to internal conflicts, power struggles, and the breakdown of governance structures, creating fertile ground for extremist groups and regional tensions. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated existing crises in the Middle East, including economic stagnation, unemployment, and governance challenges. The pandemic has strained healthcare systems, disrupted supply chains, and exacerbated socio-economic inequalities, leading to social unrest and political instability in some countries. External regional players, including regional powers and global actors, have often intervened in the internal affairs of Middle Eastern countries to further their interests. This interference has fuelled internal conflicts, exacerbated divisions, and hindered regional stability and cooperation efforts. Additionally, competition for control over strategic resources, such as oil and gas reserves in the Mediterranean Sea, has intensified regional rivalries and conflicts.

Overall, the Middle East faces significant challenges and uncertainties in the years ahead, but opportunities also exist for positive change through dialogue, cooperation, and inclusive governance. The future world order will likely be shaped by how these challenges are addressed and how regional and global actors navigate the complex dynamics of the Middle East.

Regional Powers Influence

The West Asia and North Africa (WANA) region is characterised by the competing interests and ambitions of regional and global powers. The rise of Islamic parties in countries like Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt, often backed by Turkey and financial support from countries like Qatar and Saudi Arabia, reflects a broader trend of political Islam gaining ground in the region. The extent of external influence in shaping political outcomes in these countries is a subject of debate and concern, particularly regarding their potential destabilising effects.

Turkey’s pursuit of a Neo-Ottoman policy, coupled with its support for the Muslim Brotherhood, reflects Ankara’s aspirations to assert itself as a regional power and influence events in the wider Muslim world. This has led to tensions with other regional players and raised concerns about Turkey’s intentions and actions among Western allies. It was Turkey, the Pakistan of West Asia, that allowed its territories to be used by mercenaries from all over the world. It trained and armed them fully and sent them across Syria and Iraq. More than 1,37,000 mercenaries from more than 83 nationalities entered Syria and fought alongside ISIS and al Qaeda terrorist organisations. More than 6 million Syrians were forced to migrate outside Syria.

There are more than two million kids in refugee camps in neighbouring countries who never went to school and are subjected to exploitation. The Syrian refugees live in pathetic conditions and are denied basic needs to survive. While Syria is trying to liberate its territories from the USA-Turkey occupation and rebuild Syria to encourage refugees to return, the USA continues to impose harsh economic sanctions, making life hood more difficult for citizens.

Israel, on its part, continues its policy of weakening Syria, supporting the jihadists, and opening makeshift hospitals on the occupied Syrian Golan. At the same time, it pursued a policy of attacking Syria military installations, killing Syrian civilians, Lebanese fighters, and Iranian advisors till the last attack on the Iranian consulate in Damascus that killed a prominent Iranian official in violation of the Geneva Convention.

Ever since the Iranian revolution in 1979, removing CIA agents, closing the Israel embassy in Tehran and opening a Palestinian embassy instead, Iran has been subjected to harsh economic and military sanctions by the US, and carrying out, along with Mossad Israel intelligence, covert operations targeting scientists and prominent figures.

Iran’s efforts to expand its sphere of influence in the region, particularly through its support for groups like Hamas in Palestine-occupied territories, Hezbollah in Lebanon, and various factions in Iraq and Syria, have contributed to the formation of what is often referred to as the Axis of Resistance. This axis represents a challenge to Western interests and alliances in the region and has prompted reactions from other regional and global powers.

The mysterious demise of the Iranian president and foreign minister in an American-made B212 chopper crash, along with senior officials, added more challenges to the already volatile situation in the region. The investigation team will find out whether the death was due to a technical fault in the chopper that carried the president and his team or whether it was an act of terror carried out by an adverse state that caused the tragic incident. The outcome of the investigation will determine the course of events in West Asia.

Global Power Competition

The evolving dynamics in the WANA region, including the growing influence of regional players and the involvement of external powers such as Russia and China, have implications for global power dynamics. The United States, in response to perceived challenges from Russia and China, may seek to rally its allies, including through NATO, to counterbalance these forces and maintain its influence in the region. The Russian influence in the region increased significantly in spite of the West pressure

The NATO countries made a new International Security Arrangement in June 2022. The new Strategic Concept describes the new security reality facing the Alliance, reaffirms NATO’s values, and spells out NATO’s key purpose of ensuring the Allies’ collective defense. Russia remains a threat to NATO members, and China’s growing influence politically, economically, and militarily is a matter of concern for future systemic challenges.[4]

China, seeking a wider role, succeeded where the US failed in the rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran and was able to strike a deal that eased the tension between the two leading Islamic states. Beijing kept a good relationship with the region’s stakeholders and avoided political intervention in any country’s internal affairs. The Belt Road Initiative (BRI) changed China’s doctrine. It started searching for a foot on the ground in countries that fell in the line of the route and trying to find fault lines of the West’s mischievous in the region without crossing the redlines set by the US, which considered itself the custodian of the gulf region. The recent China-Arab States Cooperation Forum held in Beijing on May 30, 2024, highlighted the importance of achieving security and stability, ending internal interference in the affairs of each nation, respecting the sovereignty of the state, stopping the Israel war on Gaza, and calling for a peaceful solution and a two-state solution to the conflict. All these political issues of mutual concern should cement the economic and trade bonds between the two nations.[5]

The tension between China and the US/Western world has reached a peak, fuelled by China’s growing competition, particularly in technology (5G), the arms market, infrastructure, and strategic connectivity projects.[6] The partial withdrawal of US forces from Iraq has implications for regional power dynamics and the balance of power vis-à-vis Israel and other actors in the Middle East. The potential strengthening of resistance forces against Israeli occupation is viewed as a threat to the strategic partnership between the US and Israel. In US perception, the threat of terrorism still looms large in Iraq as ISIS is still active and any US troops’ withdrawal will leave a vacuum that Iran could exploit. The US inflamed tensions after the killing of Qasem Soleimani and Muhandis Abbas, leader of the Popular Mobilization Forces, on January 3, 2020. The Iraqi government demanded the US remove its troops and refused to allow its territory to become a battleground between the US and Iran.

Syria: A Forgotten War

Syria holds a pivotal position in the Middle East due to its geographical location, history, and cultural diversity. Situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, Syria serves as a bridge between the continents. Its location has made it a crucial centre for trade and cultural exchange throughout history. The country’s geography includes fertile plains, mountains, and access to important waterways like the Euphrates River, which have sustained civilisations for millennia.

Syria boasts a rich historical heritage dating back to ancient times. It is often referred to as the “cradle of civilisation” due to the numerous ancient cultures that flourished within its borders, including the Mesopotamians, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Assyrians, Greeks, and Romans. These civilisations have left behind a wealth of archaeological treasures, including the ruins of Palmyra, the ancient city of Aleppo, and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. Syria is home to a diverse array of ethnicities, religions, and languages. The majority of the population is Arab, but there are also significant Kurdish, Armenian, Assyrian, and Turkmen communities, among others. This diversity is reflected in Syria’s linguistic landscape, with Arabic being the official language and other languages like Kurdish, Armenian, and Aramaic also spoken by various communities. Syria is one of the few places where ancient languages like Aramaic are still spoken. Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus Christ, continues to be used in small villages such as Maaloula, Jabaadin, and Bakhaa, primarily by Christian communities. This linguistic heritage is a testament to Syria’s long and complex history. Syria was safe and peaceful by all means till US foreign intervention and policy of clean breaks implemented and started supporting and funding banned Muslim Brotherhood organisation secretly, and turning Syria into Afghanistan in the making.

The brutal war in Syria began in 2011. Syrians, inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings in other Arab countries, began peaceful demonstrations demanding a better life and greater political freedoms. They hoped this would lead to government reforms. However, the situation escalated when the West, along with regional allies like Turkey and some Arab states, intervened. They provided billions of dollars in support, training and arming various rebel groups, including some extremists. This intervention, intended to topple the Syrian government, contributed significantly to the violence.

The war has caused immense suffering for civilians. All sides have been responsible for atrocities, including the bombing of civilian targets, use of child soldiers, and destruction of public infrastructure. The UN has confirmed the use of chemical weapons by extremist groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda. However, the West has falsely accused the Syrian government of the same, aiming to demonise the government and topple the President. This complex situation has fuelled a humanitarian crisis, forcing millions of Syrians to flee the country and has raised fears of Syria’s fragmentation.[7]

The conflict in Syria has now become a focal point for various regional and international actors due to its strategic significance and complex web of alliances. The West and the US see the Syrian government led by President Bashar Al-Assad, as a key ally of Iran and Hezbollah, and therefore, they aim to weaken Iran’s influence by supporting opposition forces in Syria. Conversely, Russia perceives the fall of Syria as potentially empowering Turkey and increasing Islamic influence in the region, which could align with US and Western interests in containing Iran. As a result, both Russia and Iran came to support. Along with the Syrian army, the Lebanese Resistance Forces and the Iraqi popular fronts, have succeeded in neutralising ISIS and al Qaeda. However, the US occupied Northern Eastern part of Syria and created a separate enclave to create an autonomous Kurdish region led by separatist faction PKK which is designated by US itself as a terrorist outfit. The PKK shelters more than 55,000 ISIS cadets while looting Syrian oil and natural resources.

The concept of redrawing the map of the Middle East, as proposed by some US scholars and military experts, reflects efforts to reimagine regional boundaries and configurations in alignment with perceived strategic interests. This includes considerations such as ethnic and religious demographics, as well as geopolitical objectives. However, such proposals are highly contentious and raise significant ethical, political, and practical challenges.

India‘s Strategic Considerations

The spillover of Israel’s war on Gaza was felt at the Red Sea with regular attacks by Ansar Allah (Houthi) of Yemen, who threaten all ships to Israel till it stops its war on Palestinians. They started attacking by drones and missiles on military and commercial vessels, which led to the militarisation by the West of the Red Sea and to the launch of military operations by Western navies in a bid to protect the mercantile shipping transversing in the area. The US Navy deployed two aircraft-carrier task groups to the region. The US, along with the United Kingdom, Bahrain, Canada, France, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Seychelles, and Spain, launched Operation Prosperity Guardian (OPG) in response to the Houthi-led attacks on shipping in the Red Sea.[8]

With the geopolitical situation becoming increasingly complex and uncertain, India, driven by oil and food security and as a trusted ally in the gulf region, has been quick to grab the opportunity and secure its presence in the Gulf states by signing bilateral agreements with each one to protect its national interests. Moreover, India has strengthened its ties with the US and has become actively involved in Gulf security by signing several security deals, conducting joint military exercises, and free trade agreements. With the US becoming more focused on the Indo-Pacific Oceans, Asia could offer a solution. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, New Delhi has become more concerned about asserting its strategic supremacy in the region, competing with Beijing, and positioning itself as the natural power to establish security and ensure new partners in the Indian Ocean region. India has presented its credentials to neighbouring countries, increased the number of trips by its warships to regional countries, carried out military exercises, and provided military equipment and training. India has also engaged in joint surveillance and invested in ports to gain regional respect and influence.

Future Scenarios

The West Asia and North Africa States (WANA) region stands at a critical juncture, with competing interests and ambitions shaping its future trajectory. The actions of regional players, such as Turkey, Israel, and Iran, as well as the responses of global powers like the United States, will continue to influence events in the region and impact broader geopolitical dynamics. Possible scenarios include continued instability and conflict, attempts at regional reconciliation and cooperation, or the emergence of new power dynamics driven by changing geopolitical realities.

The future trajectory of West Asia will depend on how various internal and external factors interact in the coming years. Efforts to address root causes of instability, such as governance failures, socio-economic inequality, and regional rivalries, will be crucial in shaping the future of the region.

Author Bio: Dr. Waiel Awwad is a Senior International Independent Journalist & Political Analyst; Former President, FCC South Asia and a Distinguished Advisor (West Asia), Tillotoma Foundation.

References:

[1] The Abbasids maintained an unbroken line of caliphs for over three centuries, consolidating Islamic rule and cultivating great intellectual and cultural developments in the Middle East in the Golden Age of Islam. The Fatimid dynasty broke from the Abbasids in 909 and created separate line of caliphs in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Palestine until 1171 CE. Abbasid control eventually disintegrated, and the edges of the empire declared local autonomy. The political power of the Abbasids largely ended with the rise of the Buyids and the Seljuq Turks in 1258 CE. Though lacking in political power, the dynasty continued to claim authority in religious matters until after the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517. (7.4: The Abbasid Empire – Humanities LibreTexts).

[2] https://worldaffairs.blog/2018/04/21/debunking-10-lies-about-syria-and-assad/

[3] https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/martinkramer/files/forgotten_truth_balfour_declaration.pdf

[4] https://www.nato.int/strategic-concept/

[5] https://www.britannica.com/event/Sykes-Picot-Agreement

[6] https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202406/01/WS665a545da31082fc043ca533.html

[7] https://mecouncil.org/publication/middle-east-and-the-future-of-international-politics-me-council/

[8] https://www.idsa.in/issuebrief/The-Indian-Navy-and-Maritime-Security-in-the-Red-Sea-SNAhmed-190224