Introduction

The Indo-Pacific—spanning the Indian and Pacific Oceans—is a critical region for global trade, energy security, and geopolitical competition. Home to over half the world’s population and accounting for nearly 60% of global GDP, it serves as a central hub for maritime trade routes and economic activity. The emergence of China, characterised by its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and expanded military presence, has intensified great power competition in the region, particularly with the United States.

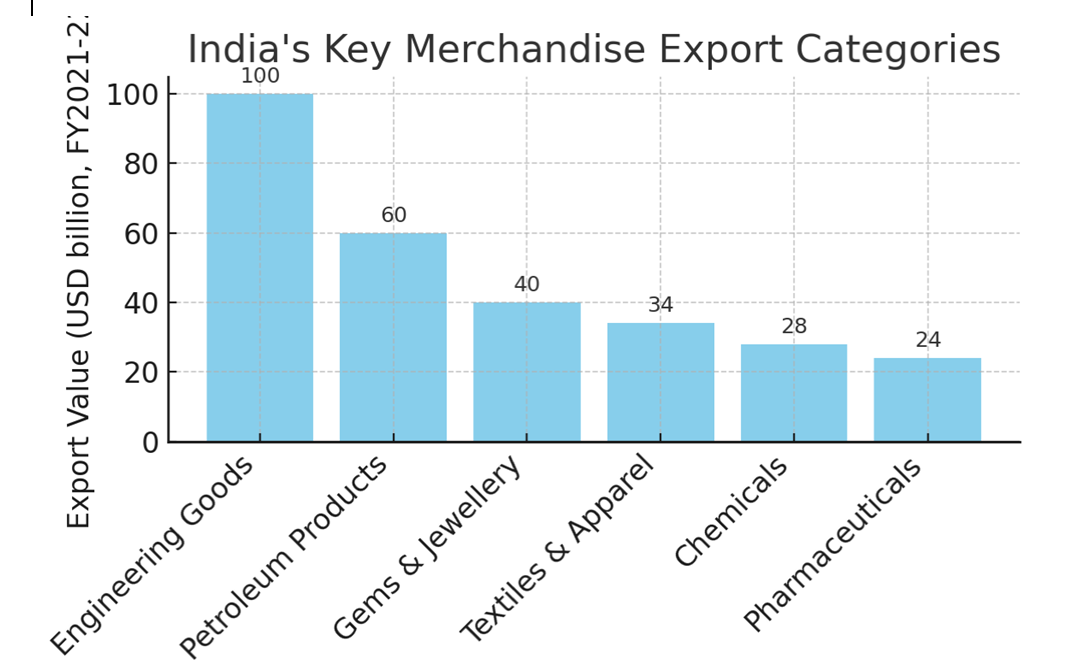

India’s trade diplomacy within the Indo-Pacific region is driven by two strategic imperatives: facilitating economic advancement and strategically containing China’s regional ascendancy. The statistics are revealing. In 2023, India’s trade-to-GDP ratio was recorded at 31%, a figure substantially below those of neighbouring nations such as Vietnam at 158% and Thailand at 112%. India faced a significant trade deficit of $83 billion with China in Fiscal Year 2023, which, alongside border tensions, necessitates stronger strategic alliances.

India’s Strategic Interest in the Indo-Pacific

India’s strategic and active engagement in the Indo-Pacific region is closely linked to its economic and security objectives. To achieve its aspiration of becoming a $10 trillion economy by 2030, it must forge strong trade partnerships and ensure a secure maritime environment. The Indo-Pacific, a crucial maritime region featuring major sea routes for communication and access to vital resources, is therefore of paramount importance.

In the evolving strategic landscape, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) holds increasing significance. India shares a distinctive and multifaceted partnership with ASEAN—encompassing trade, investment, connectivity, tourism, digital innovation, and skill development. ASEAN centrality receives India’s strong and consistent support, a principle now also embedded within the Quad, where India contributes a unique perspective as its only non-U.S. ally. As both a direct neighbour and a security partner, India remains deeply engaged with ASEAN’s regional priorities.

ASEAN member states account for 11% of India’s global trade, reflecting significant economic interdependence. According to the 2024 Asia Power Index, India ranks tenth among 27 nations in economic interactions, highlighting both recent progress and the potential for deeper integration. The findings underscore the necessity for enhanced strategic engagement and economic diplomacy to fully capitalise on the dynamic markets of the Indo-Pacific—and indicate India’s growing ambition to expand its role in regional trade diplomacy.

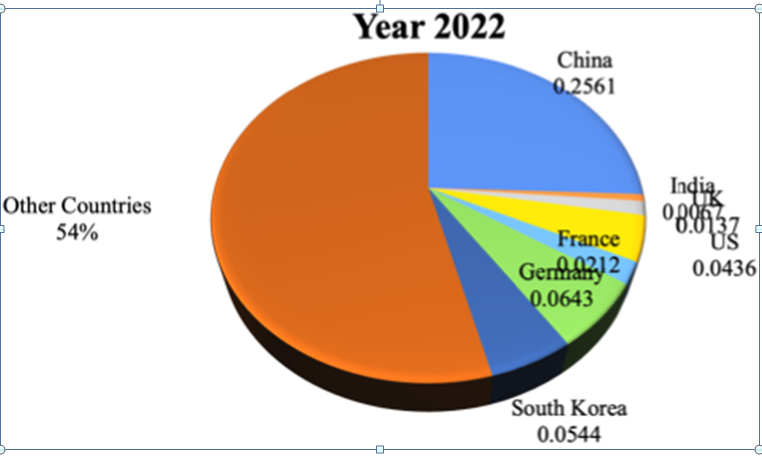

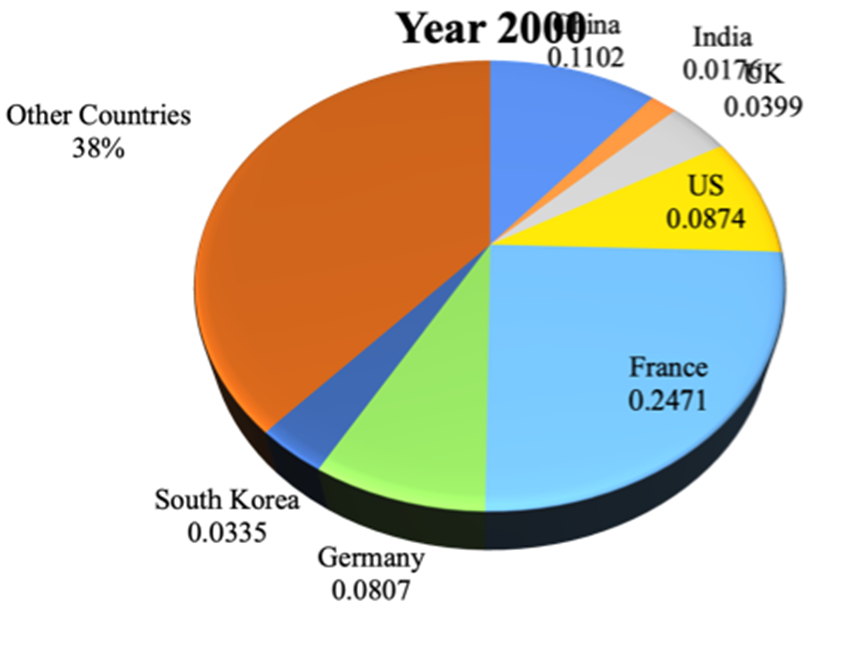

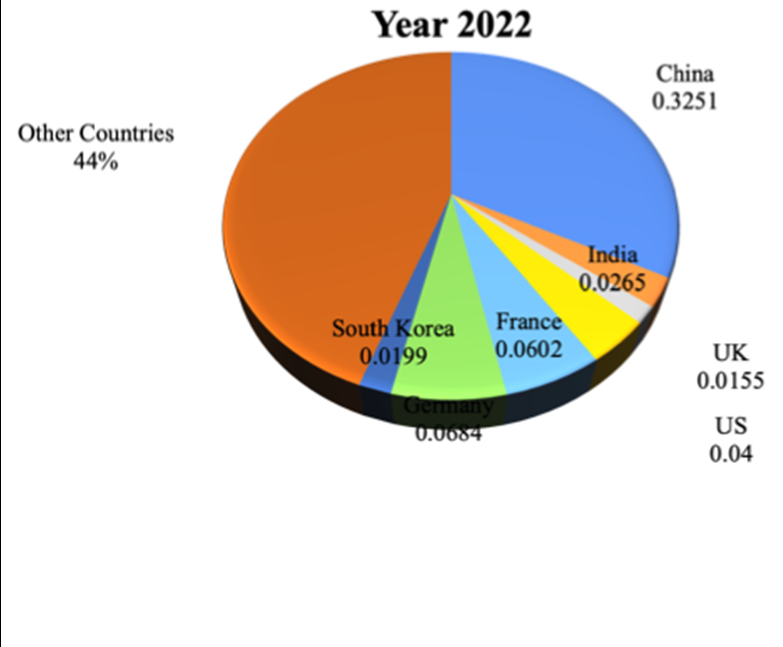

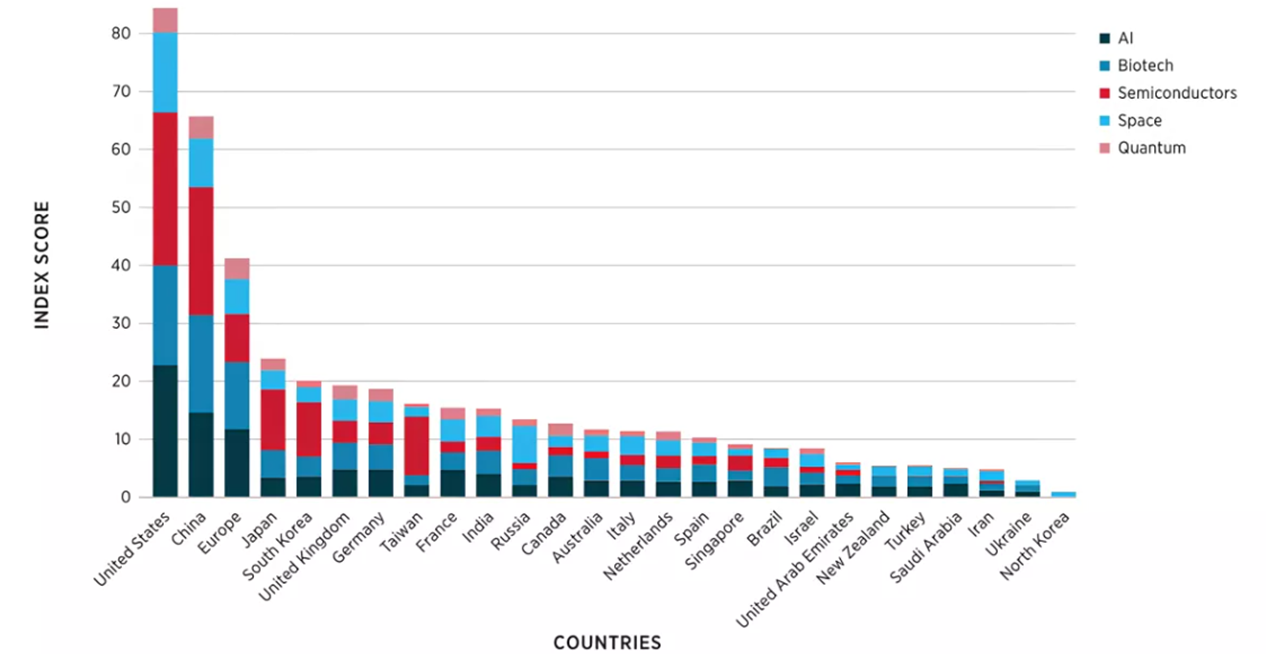

At the same time, China’s decisive actions pose significant security challenges. The Belt and Road Initiative has expanded China’s influence in India’s immediate region, including Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Border disputes, notably those of May 2020 and November 2022, along with China’s ongoing obstruction of India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group and its ambitions within the UN Security Council, have considerably heightened tensions in the bilateral relationship. India’s economic diplomacy seeks to strengthen resilience and build strategic alliances to counterbalance China’s regional ascendancy.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD)

In 2007, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe proposed the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), bringing together the United States, India, Japan, and Australia. The objective was to facilitate a “free and open Indo-Pacific” through a series of discussions and deliberations focusing on maritime cooperation. Geopolitical tensions in the Indo-Pacific, heightened by China’s growing influence in the South China Sea and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), resulted in the formation of the Quad as a response. While initially effective in disaster relief, the Quad struggled with multiple issues. Facing Chinese pressure, Australia withdrew in 2008, and India’s policy of non-alignment added further complexities, leading to the Quad’s effective disbandment, demonstrating the challenges of establishing multilateral security alliances in the region.

Driven by escalating geopolitical tensions, particularly China’s military expansion in the South China Sea and border clashes like Doklam with India, the Quad was revitalised at the 2017 ASEAN Summit. This resurgence indicated shared concerns about China’s growing economic power and its challenge to established global norms. Over time, regular summits and discussions at the foreign minister level have become a characteristic feature, with the Quad’s focus broadening to include key technologies, climate change resilience, and diversifying supply chains.

The Quad seeks to strengthen India’s Act East Policy and the SAGAR initiative, thereby enhancing its strategic position within the Indo-Pacific and addressing the challenge posed by China’s increasing regional hegemony, particularly following the 2020 Galwan clash. It bolsters India’s maritime security, trade diplomacy, and access to advanced technologies, although it requires a careful balance between maintaining strategic autonomy and pursuing deeper alignment. The Quad’s promotion of a multipolar Indo-Pacific reinforces India’s stance against the expansion of Chinese influence while also contributing to regional stability. Furthermore, the cultivation of democratic alliances significantly elevates India’s international stature.

Efforts such as the QUAD Vaccine Partnership and collaborative endeavours in cybersecurity and telecommunications aim to counterbalance China’s technological advancements. The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) initiatives in India, encompassing sectors such as electronics and drones, align seamlessly with the QUAD’s emphasis on enhancing supply chain resilience. India can strengthen its defence through the QUAD’s joint military exercises, like the Malabar drills, and intelligence sharing. Projects such as the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway serve as a counter and an alternative to China’s BRI. By participating in the Quad as one of its crucial partners, India can maintain a competitive stance with China while preserving pragmatic diplomatic ties.

Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF)

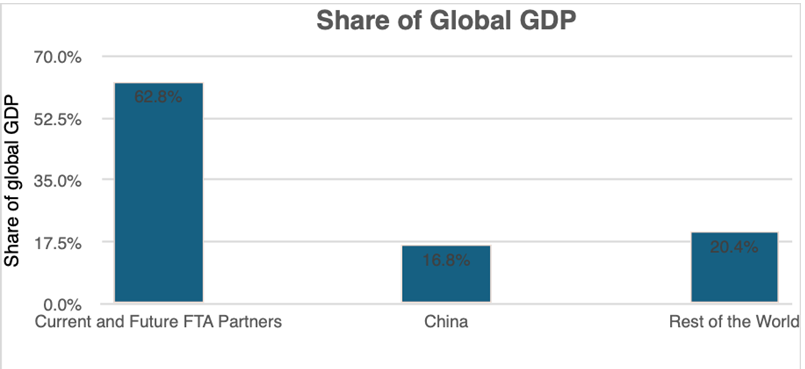

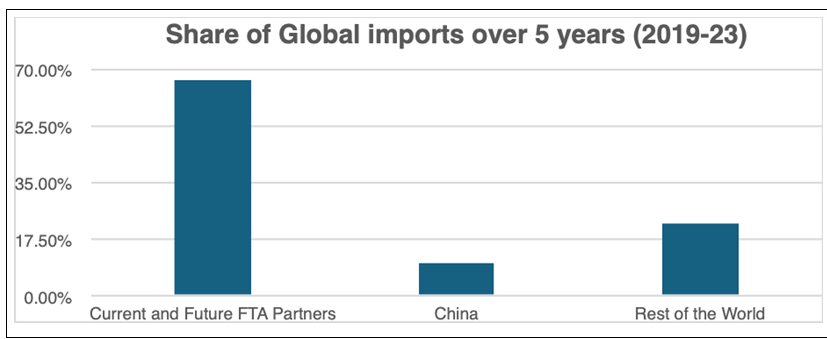

On 23 May 2022, the ‘Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity’ was inaugurated by the United States in Tokyo, with thirteen founding partners, including India. Its objective is to advance economic collaboration across four principal domains: trade, supply chains, clean energy and infrastructure, and tax and anti-corruption measures. The IPEF, which accounts for 40% of global GDP, distinguishes itself from conventional trade agreements by emphasising resilience, sustainability, and inclusivity over mere tariff reductions. This methodology embodies insights from the United States’ exit from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017. The framework emerges as a development from the Biden administration’s strategic “Pivot to Asia,” while also reflecting Japan’s Indo-Pacific vision initially expressed by Shinzo Abe in 2007.

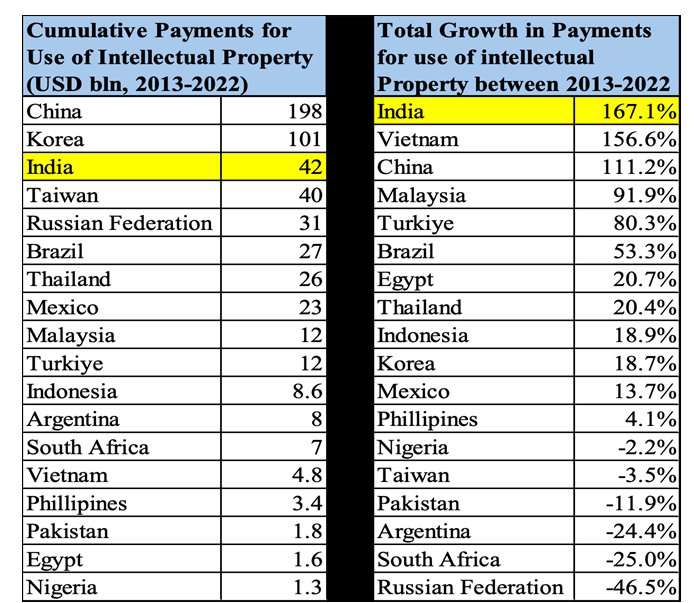

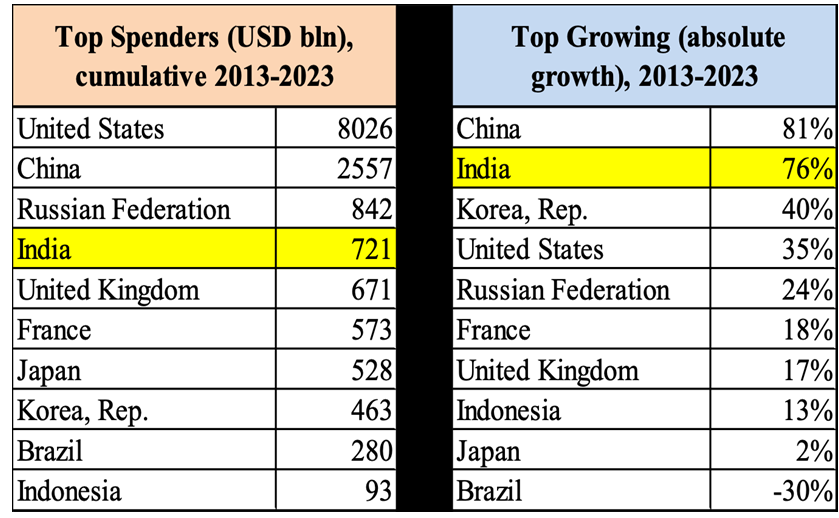

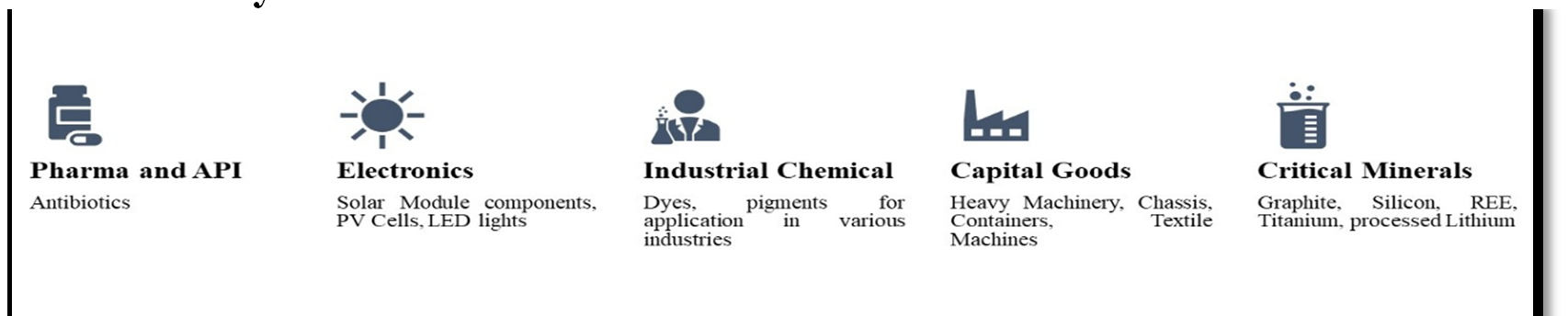

The IPEF serves as a strategic counterweight to China’s economic influence, particularly when contrasted with the Belt and Road Initiative and China’s role in RCEP, which India declined to join in 2019. By intentionally excluding China, the IPEF aligns with the QUAD goal of promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific. This strategic positioning directly addresses China’s actions in the South China Sea and its methods of economic coercion. India’s engagement significantly enhances its Act East Policy and strengthens relationships with ASEAN and Quad partners. Furthermore, the IPEF’s emphasis on augmenting supply chain resilience, particularly through the 2023 Supply Chain Resilience Agreement, aims to reduce India’s dependence on Chinese supply chains in critical industries such as pharmaceuticals and technology. Nevertheless, the current elevated tariffs and protectionist measures in India could impede the realisation of the full advantages offered by the IPEF unless these are harmonised with the framework’s inherent flexibility. The IPEF also reinforces India’s geopolitical stature by furthering economic integration and partnerships while maintaining its strategic independence in the context of the ongoing U.S.-China rivalry.

Free Trade Agreements with ASEAN and Australia

India’s endeavour to establish Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with key strategic partners, such as ASEAN and Australia, signifies an important element of its foreign economic policy, designed to stimulate economic integration and enhance its geopolitical stature in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond. The ASEAN-India Free Trade Area (AIFTA), which has been in effect since 2009, serves as a notable illustration of this ambition. AIFTA has been instrumental in systematically reducing tariffs and various trade barriers between India and the ten ASEAN member states, covering the domains of goods, services, and investment. This approach has led to a significant enhancement in bilateral trade, achieving an impressive total of $122.67 billion in the fiscal year 2023-24. The burgeoning trade dynamics have unveiled marked disparities, particularly a persistent trade deficit nearing $44 billion for India. While some sectors like pharmaceuticals, automobile components, and agricultural products have shown growth in exports, numerous challenges persist. Non-tariff barriers, including sanitary and phytosanitary regulations, technical standards, and complex rules of origin, continue to impede the smooth flow of trade. The intricate customs regulations across different ASEAN nations also pose significant operational hurdles for Indian businesses.

In contrast, the India-Australia Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA), established in 2022, represents a significant step forward in enhancing bilateral economic collaboration. The extensive provisions of ECTA for eliminating tariffs on a substantial majority of goods traded between the two countries provide India with improved access to vital resources, including critical minerals, energy, and cutting-edge technologies. The arrangement offers Australia a considerable opportunity to engage with India’s vast and rapidly growing consumer market. In addition to the immediate economic benefits, both AIFTA and ECTA contribute to advancing strategic objectives for India.

The significance of these FTAs lies in their ability to expand India’s trade portfolio, reduce reliance on specific markets, and enhance the robustness of supply chain resilience. Furthermore, in an era characterised by geopolitical instability, these agreements serve as essential tools for countering the economic hegemony of other major powers and strengthening India’s position as a key player in the evolving global economic framework. They promote improved integration within regional and global value chains, facilitate the transfer of technology and innovation, and elevate India’s diplomatic presence in international arenas. The Free Trade Agreements that India has established with ASEAN and Australia go beyond mere trade liberalisation; they are integral to a comprehensive approach aimed at fostering economic development, enhancing geopolitical standing, and reinforcing its strategic independence on the global stage.

India’s Trade Diplomacy as a Countermeasure to China

India’s trade diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific, a region that constitutes 63% of global GDP and over 50% of international maritime trade, has become a fundamental aspect of its foreign policy, demonstrating its aspiration to be a significant economic force. Evolving from the Look East Policy established in the 1990s, India’s involvement with the region has intensified with the introduction of the Act East Policy in 2014. This initiative focuses on economic, strategic, and cultural aspects to strengthen connections with Southeast Asia and beyond. This development has established India as an engaged collaborator in efforts such as the Quad and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), thereby enhancing its influence in advocating for a rules-based regional order.

Through the strategic utilisation of its dynamic IT and pharmaceutical industries, India has established a distinct position within global value chains, with trade agreements such as the India-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement enhancing export opportunities. The formation of strategic alliances with Japan and Australia, exemplified by the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor, spotlights India’s commitment to sustainable infrastructure development, providing viable alternatives to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

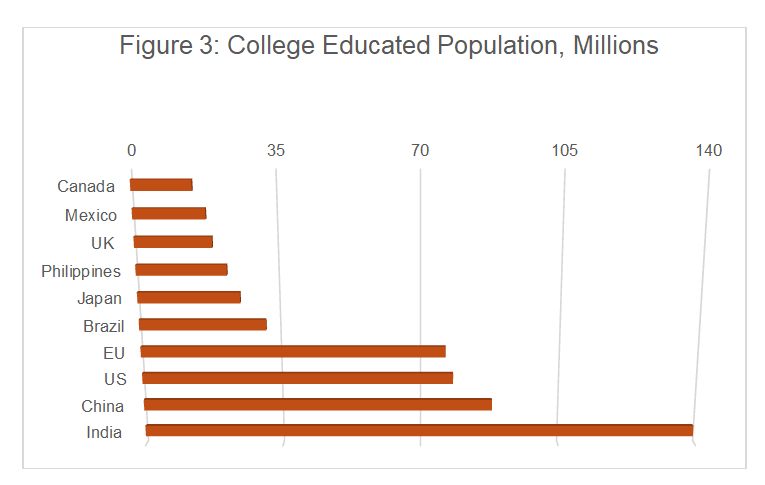

Nonetheless, India’s aspirations in trade face significant hurdles. In terms of economic performance, it lags behind China, which recorded a trade volume with ASEAN of $975.3 billion in 2022, compared to India’s $131.5 billion. Additionally, China’s substantial foreign direct investment continues to worsen this disparity. India’s protective economic measures, marked by high import tariffs averaging 13.8%, along with its decision to withdraw from the RCEP due to concerns regarding Chinese imports, have limited market access and obstructed integration within regional trade frameworks.

The complexities of geopolitical tensions, particularly highlighted by the 2020 Galwan Valley clash, impede India’s ability to navigate the delicate interplay between economic collaboration and strategic competition with China. Furthermore, India’s limited capacity to finance large-scale infrastructure projects undermines its competitiveness against the extensive influence of the BRI. Addressing these challenges through innovative trade initiatives and regional integration is vital for India to strengthen its economic presence in the Indo-Pacific.

The Way Forward

India’s strategic and trade diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific is at a pivotal moment amid ongoing geo-economic shifts. India must adopt innovative strategies to reinforce its regional influence, narrowing the economic gap with China, navigating rising protectionism, managing geopolitical frictions, and overcoming infrastructure deficits. Key initiatives aligned with the Act East Policy and the SAGAR (Security and Growth for All in the Region) vision focus on deepening economic ties, promoting sustainable development, and countering China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) through strategic partnerships and forward-looking frameworks.

Enhancing Infrastructure Collaboration

Collaborating with Quad partners—Japan, the United States, and Australia—India should seek to revitalise the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC) as a strategic counter to China’s Maritime Silk Road. This could involve establishing a dedicated task force within the appropriate line ministry to streamline project execution, exploring joint funding initiatives with Japan in Southeast Asia and Indian Ocean coastal nations—particularly in ports, roadways, and renewable energy—and leveraging the Quad’s infrastructure coordination group to align investments with regional needs, including clean energy efforts in Indonesia and Vietnam.

To enhance its maritime connectivity and diversify port access, India could contemplate joining Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI). As a Japan-led initiative promoting transparent and sustainable infrastructure, PQI offers opportunities for co-financing strategic projects—such as a deep-sea port in Indonesia—as viable alternatives to China-funded ports.

Formulating a Comprehensive Digital Trade Framework

The rapidly expanding digital economy, projected to reach $2 trillion in e-commerce by 2030, presents yet another avenue for strategic engagement. India is poised to lead efforts towards establishing an Indo-Pacific Digital Trade Agreement (IPDTA) within the ASEAN-India framework, with a focus on enabling cross-border data flows, strengthening cybersecurity, and formulating shared digital standards. Collaborating with Singapore and South Korea to establish reliable digital infrastructure, such as 5G networks, while also empowering Indian SMEs through capacity-building programmes inspired by Canada’s trade initiatives, will significantly improve market access. A pioneering digital trade corridor with Singapore has the potential to enable effortless e-commerce and data exchange, thereby establishing India as a frontrunner in the realm of digital trade.

Promoting Sustainable Trade Practices

Advancing sustainable trade practices will set India apart from the widely debated Belt and Road Initiative of China. By initiating a Green Trade Initiative within the SAGAR framework, India has the potential to export cutting-edge clean energy solutions, including solar panels, to ASEAN nations. Collaborating with Australia to ensure the stability of critical mineral supply chains for batteries will reduce dependence on Chinese markets. Furthermore, a regional fund, supported by the Quad, aimed at fostering climate-resilient infrastructure, can provide vital assistance to Pacific Island Countries. Implementing solar-powered microgrids in the Maldives would significantly enhance energy security while simultaneously mitigating China’s regional influence.

Enhancing Regional Cohesion

To enhance regional integration while abstaining from participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), India could engage in bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) with Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines, focusing on reducing tariffs on pharmaceuticals and IT services. Strengthening the India-ASEAN Comprehensive Strategic Partnership through trade facilitation initiatives, such as single-window customs clearance, and integrating the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) with the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway will establish resilient trade pathways. A free trade agreement with Vietnam, for example, has the potential to boost India’s pharmaceutical exports by leveraging the opportunities within Vietnam’s healthcare market.

Utilising the Quad and Squad Frameworks

Ultimately, utilising the Quad and the emerging Squad frameworks, which include the United States, Australia, Japan, and the Philippines, will enhance India’s strategic influence. The establishment of a Quad Trade and Technology Council to harmonise policies regarding semiconductors and clean energy, the consideration of Squad inclusion to safeguard trade routes in the South China Sea, and the organisation of annual Indo-Pacific Trade Summits will significantly bolster supply chain resilience. A supply chain initiative supported by the Quad, drawing upon the Australia-Japan-India framework, has the potential to diversify essential technology networks, thereby mitigating the economic coercion exerted by China.

These collective efforts enhance India’s trade diplomacy, promoting a multipolar Indo-Pacific framework while simultaneously addressing the strategic rivalry with China. By aligning domestic reforms with regional aspirations, India has the potential to consolidate its status as a premier economic force within the region. These initiatives correspond with India’s vision for a liberated and accessible Indo-Pacific, highlighting the significance of a rules-based trading system and maritime security. By emphasising sustainable and refined alternatives to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, India could cultivate trust with regional partners cautious of Beijing’s debt-driven strategies. The enhancement of digital trade and collaborative infrastructure initiatives will position India as a leader in emerging sectors, thereby narrowing the economic gap with China. India must also tackle local challenges, such as refining regulatory frameworks and minimising tariffs, to fully realise this potential.

Author Brief Bio:

Ruchira Kamboj: Ambassador Ruchira Kamboj is a distinguished officer of the 1987 batch of the Indian Foreign Service. She served as India’s first female Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York until May 2024, where she led key initiatives and made history in December 2022 by becoming the first Indian woman to preside over the UN Security Council. Her trailblazing path includes being India’s first female Ambassador to Bhutan, High Commissioner to South Africa, and Permanent Representative to UNESCO in Paris—each role marked by significant contributions to India’s strategic and cultural diplomacy. From 2011 to 2014, she served as India’s first woman Chief of Protocol, overseeing high-level diplomatic engagements that enhanced India’s global profile. Earlier in her career, she held key postings in Paris, Mauritius, New York, and Cape Town, and from 2009 to 2011, she was seconded to the Commonwealth Secretariat in London as a staff officer to the Secretary-General. She is a Member of the Governing Council of India Foundation.

Chitra Shekhawat: Ms. Chitra Shekhawat is currently working as a Research Fellow at India Foundation. She completed her Masters and B. A. Honours in Economics from St. Xavier’s College, Jaipur where she was elected as a Cultural Secretary of the Student Council. Her area of interest lies in the fields of development economics, good governance, public policy and advocacy.

References:

Saha, Premesha. “India’s growing strategic footprint in the Indo-Pacific” orfonline.org, 23 Aug. 2023, www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-growing-strategic-footprint-in-the-indo-pacific

“The Indo-Pacific in Indian Foreign Policy.” Royal United Services Institute, www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/policy-briefs/indo-pacific-indian-foreign-policy.

India Signs First-of-its-kind Agreements Focused on Clean Economy, Fair Economy, and the IPEF Overarching Arrangement Under Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2057489.

Wikipedia contributors. “Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.” Wikipedia, 1 Feb. 2025, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Pacific_Economic_Framework.

“Free Trade Agreements Between India and ASEAN Countries.” Invest India, www.investindia.gov.in/blogs/free-trade-agreements-between-india-and-asean-countries.

“Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement (ECTA).” Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/australia-india-ecta.

Rossow, Richard, and Richard Rossow. “India’S Diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific Has an Economic Hole. Fill It With Trade, Investment.” ThePrint, 3 Mar. 2025, theprint.in/opinion/india-economic-diplomacy-indo-pacific-trade-investment/2301558.

The Financial Express. “Blowing Hot and Cold.” Financial Express, 21 June 2023, www.financialexpress.com/opinion/blowing-hot-and-cold/3136415.

Monika Yadav, and Monika Yadav. “Goods Exports to China Fall 28% in FY23.” The New Indian Express, 14 Apr. 2023, www.newindianexpress.com/business/2023/Apr/14/goods-exports-to-china-fall-28-in-fy23-2565813.html.

India Today. “NSG: The Great Wall of Xi.” India Today, 1 July 2016, www.indiatoday.in/the-big-story/story/20160711-nsg-membership-india-china-829187-2016-06-30.

ET Bureau. “China Only P5 Nation Opposing India’s UNSC Entry: S Jaishankar.” The Economic Times, 5 Aug. 2023, m.economictimes.com/news/india/china-only-p5-nation-opposing-indias-unsc-entry-s-jaishankar/articleshow/102458250.cms.

Invest India, www.investindia.gov.in/production-linked-incentives-schemes-india

Team, Next Ias Current Affairs. “India and Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) for Prosperity – Current Affairs.” Current Affairs – NEXT IAS, 5 Nov. 2024, www.nextias.com/ca/editorial-analysis/05-11-2024/india-and-indo-pacific-economic-framework-ipef-for-prosperity.

Press Trust of India and Business Standard. “India Signs IPEF Bloc’s Clean, Fair Economy Agreements to Boost Cooperation.” www.business-standard.com, 22 Sept. 2024, www.business-standard.com/economy/news/india-signs-ipef-bloc-s-clean-fair-economy-agreements-to-boost-cooperation-124092200218_1.html.

Desk, Explained. “India Accepts Three Out of Four Pillars of US-led IPEF, so Why Has It Stopped Short of a Total Agreement?” The Indian Express, 10 Sept. 2022, indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-economics/us-ipef-india-accepts-three-pillars-stopped-short-total-agreement-8142554.

India’s evolving trade strategy with ASEAN: https://www.orf.org/expert-speak/india-s-evolving-trade-strategy-with-asean

“India Seeks Greater Market Access, Flexibilities in Rules of Origin in FTA Review With ASEAN.” BusinessLine, 7 Mar. 2024, www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/india-seeks-greater-market-access-flexibilities-in-rules-of-origin-in-fta-review-with-asean/article67925058.ece.

Pandit, Rajat, and Times Of India. “India Hands Over Warship to Vietnam, With an Eye on China.” The Times of India, 23 July 2023, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/india-hands-over-warships-to-vietnam-with-an-eye-on-china/articleshow/102043200.cms.

Peri, Dinakar. “Philippines Inks Deal Worth $375 Million for BrahMos Missiles.” The Hindu, 28 Jan. 2022, www.thehindu.com/news/national/philippines-inks-deal-worth-375-million-for-brahmos-missiles/article38338340.ece.

SEA PHASE OF ASEAN-INDIA MARITIME EXERCISE – 2023. pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1922815.

“Two Years of Indo-Pacific Strategic Results: Strengthening Indo-Pacific Commerce for a Prosperous Future.” U.S. Department of Commerce, 9 Feb. 2024, www.commerce.gov/news/fact-sheets/2024/02/two-years-indo-pacific-strategic-results-strengthening-indo-pacific.

“The Geopolitics of Indo-Pacific Trade.” Royal United Services Institute, www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/conference-reports/geopolitics-indo-pacific-trade.

Deshpande, Prashant Prabhakar. “India’s Indo-Pacific Strategy to Counter China.” Times of India Voices, 14 Aug. 2023, timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/truth-lies-and-politics/indias-indo-pacific-strategy-to-counter-china.

Bhowmick, Soumya. “The Indo-Pacific Economics: Inextricable Chinese Linkages and Indian Challenges.” orfonline.org, 8 Dec. 2021, www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-indo-pacific-economics-inextricable-chinese-linkages-and-indian-challenges.

Teekah, and Ethan. “Indo-Pacific | Geopolitics, Economics, History, Climate Change, and Outlook.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 June 2025, www.britannica.com/place/Indo-Pacific.

“The Indo-Pacific Economics: Inextricable Chinese Linkages and Indian Challenges.” orfonline.org, 8 Dec. 2021, www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-indo-pacific-economics-inextricable-chinese-linkages-and-indian-challenges.