Introduction

In a world where our understanding of cultures often dissolves into the fog of preconceptions, and political ideas are reflected through the distorted mirrors of cliché, approaching the lived reality of an ancient society—especially one as layered as India—requires stepping away from ready-made narratives and towards direct experience. India cannot be understood through a single viewpoint or label; it resembles a thali—a diverse, multi-layered spread whose meaning becomes clear only when its elements are seen together rather than in isolation.

This note seeks to explore how direct interaction with groups such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) can contribute to a more accurate understanding of certain social and cultural dynamics within India—not as an endorsement or rejection, but as an attempt to situate the organisation within the broader “thali” of India’s complexity. RSS occupies an influential space in India’s public life, and that influence has generated a wide range of interpretations, often sharply divergent.

Ram Madhav, in The Hindutva Paradigm (2024), offers a thought-provoking observation: “The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is difficult to understand but easy to misunderstand” (ibid., 1). This statement does not define the organisation; rather, it underscores the importance of our method of understanding. Many external interpretations capture only one part of the picture and extend it to the whole. Direct engagement—speaking with members, observing activities, and encountering the organisation in practice—can help complete that picture, whether by confirming prior assumptions or complicating them.

Approaches rooted in distance, especially those shaped by dominant frameworks in Orientalist scholarship, tend to emphasise certain aspects of organisations, such as the RSS, while overlooking others. In contrast, firsthand experience opens space to observe the broader cultural, social, and political spectrum that becomes visible only from within. The goal is not to render quick judgments but to acknowledge the complexity that is often flattened in external analyses.

Iran and India, linked through long-standing historical ties and shared intellectual traditions, provide fertile ground for deeper dialogue and mutual understanding. This note suggests that approaches based on direct observation—including engagement with the RSS—can help us move beyond common stereotypes and towards a more nuanced, multi-dimensional view of India’s cultural, philosophical, and political landscape—one shaped not from a distance, but through direct experience.

-

The Challenge of Perception and Research Methodology

The serious, sustained study of any civilisation, particularly one as ancient, vast, and symbolically intricate as India, must commence with a fundamental critique of its own methodological assumptions. The philosopher Slavoj Žižek posed a deceptively simple yet profoundly unsettling question that serves as an essential starting point for cross-cultural inquiry: “What if the way we perceive a problem is already part of the problem?” This proposition is far more than a mere philosophical query; it is a crucial epistemic imperative when engaging with a culture defined by layered history and deep symbolic resonance. The lens through which an external observer views a complex culture—whether shaped by inherited academic paradigms, geopolitical frameworks, or prevailing media narratives—often predetermines the nature and shape of the very “problem” being analysed, as the observer is fundamentally entangled in the phenomenon itself.

This profound methodological truth was repeatedly encountered throughout the trajectory of research on South Asia, spanning from master’s-level work on the subtle concepts underlying Gandhi’s ahimsa to doctoral-level inquiries into the complexities of Hindutva and the organisational ethos of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The researcher’s own conceptual frameworks often become intrinsically woven into the landscape being surveyed, making objective distance a constant struggle.

A well-known adage shared among those who attempt to grasp India succinctly captures this recurring sense of intellectual humility and the scale of the challenge: “When you first arrive in India, you think you can write a book about it. Soon, you realise that only an article may suffice. And eventually, you understand that even a single sentence about India is profoundly difficult to write.” India is not a static object of study; it is an oceanic, multi-hued, living world of continuous experience that necessitates profound intellectual modesty and an acknowledgement of its near-infinite complexity. Every attempt to provide a singular, definitive explanation invariably uncovers new layers of complexity, thus continually reaffirming Žižek’s core warning: the means of perception are themselves entangled within the problem’s definition.

Consequently, any attempt at an authentic, academically rigorous understanding of contemporary Indian phenomena, particularly the ideological nuances of Hindutva and the structure of the RSS, must involve a deliberate and critical effort to transcend the Western constructs that have historically dominated global scholarly discourse. As articulated in Edward Said’s foundational critique, Orientalism (Said, 1978), Western scholarship has frequently constructed knowledge less as a means of genuine understanding and more as an exercise in subtle cultural power and intellectual domination. Numerous conventional Western analyses of both Hindutva and the RSS often inadvertently reflect these pre-constructed frameworks—which may be rooted in political reductionism or secularist assumptions—rather than the actual, lived realities and self-defined terms used by the Indian actors themselves.

To penetrate beyond these external analytical veils, the only effective methodology is one of direct, prolonged, and sustained dialogue. The most reliable and nuanced insights were derived from years of direct interaction with influential Indian thinkers, including Ram Madhav, and from extensive, candid engagement with a wide array of grassroots members within the RSS. The key finding was that the most authentic comprehension emerges when the voices are heard in their own terms and idiom—whether expressed in regional languages or in English, which serves as a pragmatic and crucial bridge for cross-cultural conversation—rather than relying solely on generalised, abstract, or politically charged secondary interpretations originating from external sources. This commitment to primary, experiential, and dialogic engagement is the absolute prerequisite for effectively navigating and overcoming the challenge of perception.

-

Iran and India: Mythic and Civilizational Kinship

The relationship between Iran and India is not merely one of geopolitical proximity or intermittent historical interaction; it is defined by a deep-seated, fraternal, and structural kinship. This profound connection is best captured by the timeless, powerful metaphor of Rama and Lakshmana from the Hindu epic, the Ramayana. Lakshmana is portrayed not as a mere secondary figure, but as the embodiment of unwavering ethical fortitude and constant, loyal companionship, whose presence and support are essential to Rama fulfilling his complex and challenging dharmic duties. In this same vein, Iran functions as a natural, almost mythic, counterpart—a true sibling civilisation—for interpreting and understanding India. It serves not as an external critic but rather as a co-originating cultural force whose shared roots illuminate the fundamental structures of the other. This powerful, enduring mythic analogy underscores the deep, shared foundations that inextricably bind the two great civilisations.

This conceptual parallelism extends far beyond mere literary metaphor, penetrating the core of shared linguistic, philosophical, and moral structures. In the Indian civilizational paradigm, Dharma functions as the multifaceted cornerstone defining ethical, social, and cosmic order. The term is inherently holistic, encompassing duty, law, righteousness, virtue, and the appropriate way of living in alignment with universal truth (Klostermaier, 2007). In parallel with ancient Iranian thought, closely analogous principles are manifest in Asha, which defines cosmic order, fundamental truth, and the ethical conduct necessary to maintain that order. Complementing this is Dād, which denotes the specific principles of justice, equity, and social equilibrium. A critical, unifying convergence between these two systems is the strong prioritisation of right action (praxis) over passive doctrinal belief, consistently emphasising ethical living as the highest measure of human alignment with the universal order.

This deep structural kinship is unequivocally supported by the presence of significant shared mythic symbols, most conspicuously the veneration of the sacred cow. This animal transcends its status as livestock to become a powerful symbolic entity in both cultural narratives. In Vedic texts and throughout Indian culture, cows symbolise abundance, vitality, divine insight, and the profound principle of cosmic generativity. This widespread veneration resonates deeply with parallel Iranian motifs and cultural memory. In the Avesta, the life-giving cow (gāu) is understood to embody essential cosmic energy crucial to creation and continuous sustenance.

The shared, powerful archetype is explicitly reflected in the heroic narratives of both traditions, particularly the detailed role of the cow in the Iranian narrative:

- In the Iranian national epic, the Shahnameh, the miraculous, nurturing cow named Barmaiyeh (also known as Bermaiyeh) plays a pivotal, life-saving role. Barmaiyeh provides essential sustenance and sanctuary to the young Fereydun, the hero destined to rise and ultimately overthrow the tyrant Zahhak. The cow’s presence at the start of Fereydun’s life is not merely an incidental detail; it is a profound symbolic act. Barmaiyeh embodies the life-giving, protective, and foundational energies necessary for the eventual triumph of Asha (truth/order) over the chaos and injustice represented by Zahhak. Fereydun’s ability to restore equilibrium in the realm is thus tied back directly to the sacred, nurturing entity that supported him in his infancy. The cow, in this sense, is an active agent of providence and the continuity of moral order.

- In parallel Vedic traditions, ancient heroic or semi-divine figures, such as Trita, are frequently aided—either symbolically or directly—by sacred bovines in their profound struggle to confront chaos, combat disorder, and restore the vital principle of Dharma.

In both heroic cycles, the cow serves as a consistent and vital facilitator of moral order and cosmic justice, acting as a bridge between human heroic action and the essential divine or cosmic orchestration. This symbolic and thematic continuity clearly shows that India and Iran are not merely “others” to each other; they form twin civilisations that share fundamental archetypes, deeply ingrained ethical imaginative frameworks, and identical cosmological concerns (Thapar, 2013). Fereydun’s successful restoration of balance after defeating Zahhak, rooted in the victory of cosmic law and order, closely parallels the Indian concept of dharmic heroism, as powerfully exemplified by the complex moral responsibilities borne by figures such as Rama and the Pāṇḍavas in their respective epics.

-

Shared Ethical and Spiritual Frameworks

The foundational connection between India and Iran extends well beyond shared myths and historical contact, reaching into the deepest layers of human spiritual and existential experience. This shared intellectual and moral ground is most vividly articulated through fundamental philosophical concepts and parallel poetic expressions that inherently convey profound complexity.

The Philosophical Core: Dharma and Asha (Ashé)

The intellectual bedrock of both civilisations is characterised by concepts that actively resist simple, one-to-one translation into Western languages, reflecting the unique, integrated nature of ethics, cosmic order, and societal structure within their respective worldviews.

- Dharma (India): As the quintessential framework, it encompasses duty, moral law, righteousness, and, most pivotally, ethical praxis. It serves as a comprehensive guide to individual conduct and as the mechanism for maintaining social and cosmic order (Klostermaier, 2007).

- Asha (Ancient Iran): This principle functions analogously, serving as the ultimate definition of universal truth, cosmic harmony, and the necessary ethical conduct required of humans to align with this cosmic reality.

- Dād (Iran): Complementing Asha, dād provides the specific, actionable framework for administering social justice and ensuring equitable equilibrium within the community structure.

These terms are critically important because they universally encode the principle that moral conduct is entirely inseparable from societal accountability and personal alignment with a greater, transcendent universal order. Understanding the foundational importance of Dharma and Asha—and their shared emphasis on action (praxis) over abstract belief (dogma)—is essential for interpreting both the overall trajectory of Indian civilizational thought and the practice-focused ethical framework adopted by the RSS. The core commonality is the belief that religious or traditional life is primarily defined by conduct and moral responsibility, establishing right action as the final measure of alignment with cosmic law.

The Poetics of Bewilderment: Nanak and Hafez

The sheer continuity of the spiritual quest and the expression of universal existential doubt are powerfully captured in the poetry of two great spiritual masters: Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, and the Persian poet Hafez. Both articulate a shared human predicament—the sense of spiritual and cognitive astonishment (ta’ajjub) when confronted by the immense, baffling complexity of existence. Guru Nanak gives voice to this deep sense of bewilderment and the necessity of self-search in his striking verses: “I remain astonished in the search for myself. / In darkness, I find no path. / Bewildered in pride, I weep with regret. / How can one attain salvation?” (Granth, 2004, 202, trans. Grant)

This clear expression of spiritual searching, existential confusion, and the difficulty of finding the correct moral path is mirrored with remarkable thematic fidelity in the ghazals of Hafez (Hafez, 2004): “From every side I went; nothing but astonishment increased. / Alas, this desert and this infinite path!” Hafez laments the boundless, inherently confusing nature of the spiritual and moral journey, underscoring the desperate need for guidance in the dark: “In this dark night, the path to purpose is lost; / Come forth from a corner, O guiding star.”

For the scholar, these deep thematic resonances are not merely intellectual curiosities; they provide a crucial, empathetic framework for engaging with India. They permit the researcher to view Indian civilisation not as a collection of alien or exotic practices, but as a vibrant, living tradition that grapples with the same fundamental moral and spiritual concerns that have informed and shaped Iranian intellectual and ethical traditions for millennia. The Iranian perspective, deeply rooted in its own long history of ethical reflection and heroic mythology, thus offers a uniquely natural and sympathetic lens for interpreting the core, enduring dynamics of Indian civilisation.

-

Identity, Cultural Confidence, and Introspection (The Jam-e Jam)

Civilisations that have successfully preserved a deep and continuous historical consciousness naturally cultivate a strong cultural confidence—an intrinsic and powerful awareness of their own value, the endurance of their legacy, and the vital necessity of self-preservation through ethical and moral consistency. This profound characteristic is clearly visible in the histories of both Iran and India. In the Indian context, when the socio-cultural movement of Hindutva is examined at its deepest level, it can be seen as a disciplined and deliberate expression of this very confidence: a commitment to achieving ethical and cultural coherence and to actively nurturing civic and moral responsibility among its followers.

The Allegory of the Jam-e Jam

The poetry of Hafez provides the most vivid and compelling allegory for this essential process of cultural introspection: the Jam-e Jam. This legendary cup symbolises universal insight, wisdom, and a comprehensive vision of the world. Hafez employs it to critique the human tendency to seek validation or knowledge from external sources, while the ultimate truth resides within the self and one’s own tradition. His famous couplet offers a profound and inescapable admonition for all studies of civilisation: “For years my heart sought the Jam-e Jam from others; What it possessed itself, it sought from the stranger.”

This couplet emphasises that true understanding, authentic cultural knowledge, and a grounded sense of identity must spring from within the civilisation itself. They cannot be reliably derived from external imitations, reactive criticisms, or dependence on the approval of outsiders. The Jam-e Jam, as a symbol of self-knowledge, underscores the fundamental principle that genuine cultural authenticity emerges from deep, internal reflection—not from external appropriation or copying.

RSS and the Quest for India’s Jam-e Jam

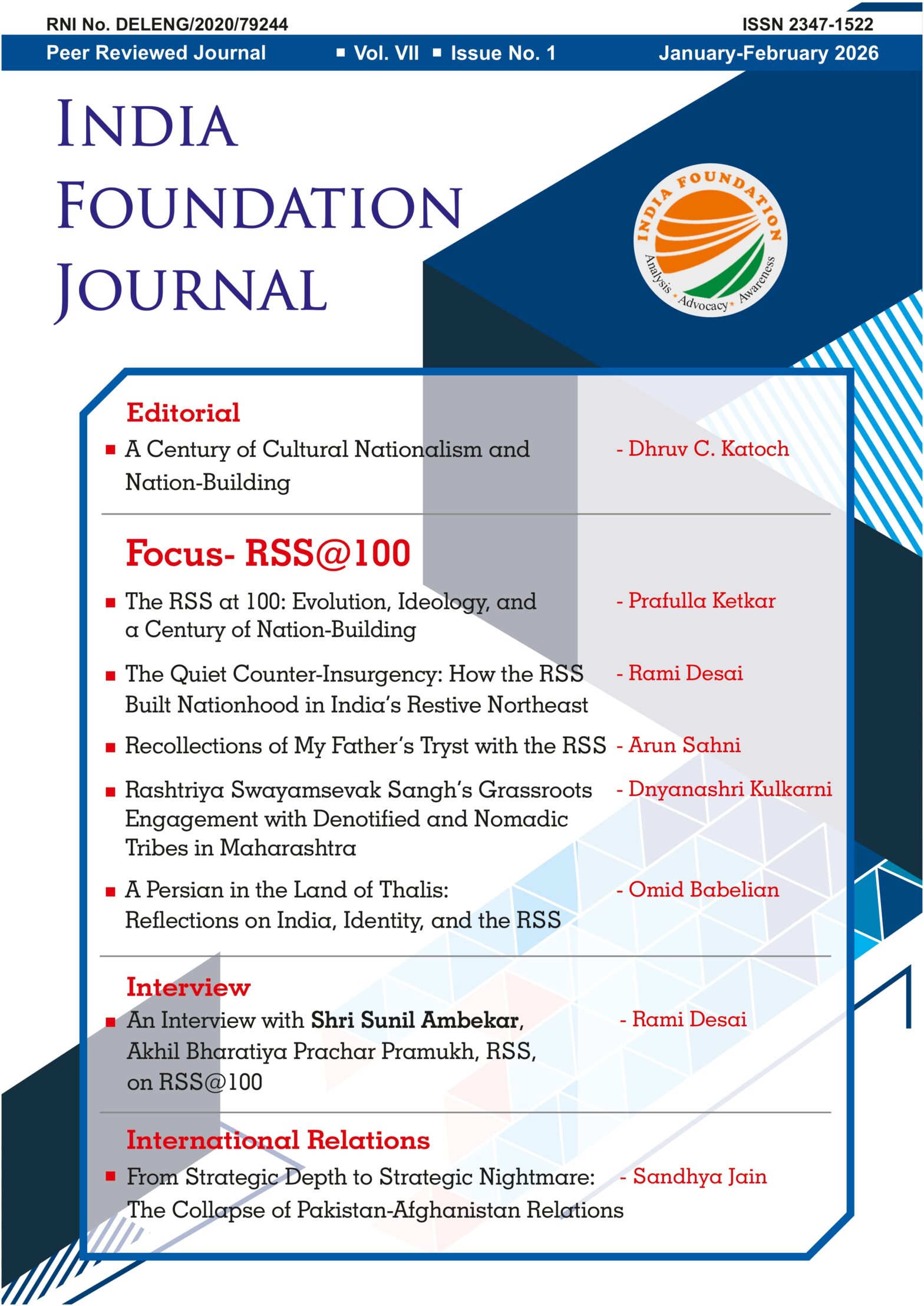

In earlier years, members of the RSS and similar organisations generally preferred to speak little about their beliefs or internal practices with outsiders. As a result, most accounts and interpretations of the organization and of Hindutva were produced by individuals outside the group, which often led to widespread misunderstandings. At times, the movement was labelled as a fascist ideology, while at other moments it was dismissed as a closed, antiquated tradition resistant to any innovation.

Fortunately, the movement’s new generation has approached public engagement with a markedly different perspective. They write fluently in English, participate actively in international conferences, and maintain high levels of dialogue and interaction. This renewed approach has not only enabled the group to be better understood but also facilitated a deeper understanding of India’s cultural heritage. A sense of cultural confidence has emerged, and when speaking with students and young people in India, this fresh understanding is immediately perceptible. Members talk with genuine enthusiasm about India’s cultural and historical legacy, as if the RSS itself is in search of its own “Jam-e Jam” for India: reclaiming, recognising, and reintroducing the rich identity and heritage of the civilisation.

-

Experiential Findings and Hindutva as Ethical Praxis

In the quest to gain a deeper understanding of Hindutva and the philosophies of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a closer examination of the positions taken by its prominent leaders is essential. One key observation in this regard is the assertion made by Mohan Bhagwat, the head of RSS, who emphasised that Hindutva cannot exist without Muslims. He stated, “If we do not accept Muslims, then it is not Hindutva. Hindutva is Indian-ness and inclusion” (as cited in Madhav, 2024, 250). This statement highlights an essential aspect of Hindutva that often goes unrecognised: it is not merely a political ideology but a vision of inclusivity that seeks to bring diverse communities together under the broad umbrella of Indian identity.

This inclusiveness is particularly evident in the everyday, voluntary activities of RSS members. Throughout India, the Sangh’s Shakhas and volunteer groups are actively engaged in crisis response efforts, such as flood relief and disaster management, demonstrating their commitment to serving society at large. These volunteers, driven by a sense of duty to their country and humanity, are not merely seeking political power or religious dominance; they are guided by a deep commitment to the moral and spiritual well-being of their nation.

This deep sense of inclusion and community service highlights the core values of Hindutva, which emphasises cultural self-realisation rather than opposing external forces. RSS, through its volunteer efforts and educational activities, aims to strengthen a shared sense of identity among all Indians, surpassing the divisions often created by external narratives.

From my own experience, and in conversations with figures such as Ram Madhav, a central question emerged: Does Hindutva aim to create a melting pot, where all groups merge into a single, homogeneous entity, or is it more akin to the thali (traditional Indian meal) where various distinct elements are served side by side, maintaining their individuality while complementing one another? The answer is not about forced homogenization but about respecting the unique flavours of each component while recognising their collective harmony. This “distinct flavour” defines Hindutva – a flavour unique to India, rooted in centuries of cultural, philosophical, and spiritual history.

This is not about exclusion, but about embracing cultural self-confidence – the confidence that I, as an Indian, possess the Jam-e Jam of my civilisation, which defines my identity. The goal of RSS, in this context, is to restore the proud and ancient identity of India or Bharat. It is a process of self-empowerment, one that seeks to reclaim the moral and cultural treasure of the civilisation that has existed for millennia, not merely as a reactionary force but as an active, reflective force of cultural revival.

The Continuity of Ethical Praxis and Conclusion

In conclusion, the Hindutva movement, when understood in its true context, goes beyond the simplistic political caricatures often imposed upon it. It is not about rejecting diversity or excluding others; rather, it is about fostering a sense of unity and shared moral responsibility among all who identify with Indian civilisation. Hindutva, as articulated by the RSS, is a call to recognize India’s ancient wisdom, cultural autonomy, and moral self-confidence. By internalizing this identity, the RSS and its followers aim to revitalize the ethical and spiritual foundations of Indian civilization, affirming that the essence of Hindutva is not division, but unity rooted in cultural pride and responsibility.

In this sense, Hindutva fundamentally seeks to restore the ethical and cultural identity of Indian society, particularly by emphasising moral action and social responsibility. Viewed through this civilizational lens, Hindutva emerges as a conscious continuation of a shared ethical lineage between Iran and India. In both civilisations, concepts like Dharma (in India) and Asha (in Iran) serve as foundational principles for aligning individual conduct with cosmic and social order. These concepts not only help define ethics and global harmony but also emphasise the primacy of ethical action (praxis) over abstract belief. In this framework, Hindutva is seen not just as a political ideology, but as a living, ethical worldview—one that actively seeks to build unity through cultural pride and moral responsibility.

Thus, much like the Jam-e Jam in Persian literature, which symbolises ultimate wisdom and truth, Hindutva also calls for an internal realisation of these truths; an ethical and cultural self-recognition. RSS and its followers aim to rejuvenate India’s moral and spiritual legacy by embracing a vision of unity, not division, rooted in cultural pride and social responsibility.

In essence, the Hindutva movement is a call to reclaim India’s heritage—not just politically, but ethically and culturally—while fostering a spirit of collective moral responsibility. This is the deeper vision of Hindutva: not merely a political stance, but a profound commitment to unity and pride in one’s civilisation, deeply rooted in the belief that a nation’s strength lies in its shared ethical traditions and cultural coherence. Through this process, RSS seeks to highlight the importance of a vibrant, living tradition; one that continuously nurtures its moral compass, ultimately bringing people together in a cohesive, ethical, and culturally proud society.

Author Brief Bio: Omid Babelian is a researcher at the Institute for Political and International Studies (IPIS), Iran’s leading think tank dedicated to Track 1.5 and Track 2 diplomacy. He holds a Master’s degree and a Ph.D. in World Studies with a specialization in the Indian Subcontinent. His doctoral research focuses on an analysis of the Hindutva discourse. Additionally, he works on the Indian Ocean region, examining the maritime dimensions of international relations and the role of regional actors in shaping global dynamics. His academic and professional work centers on the political, social, and cultural dynamics of South Asia. At IPIS, he actively contributes to research initiatives that foster dialogue and support Iran’s strategic diplomatic engagement. Beyond his regional specialization, Omid has a profound interest in cinema, the philosophy of art, political thought, and international literature. His interdisciplinary approach allows him to combine political analysis with cultural and philosophical insights, enriching his contributions to the study of international relations and global diplomacy.

References:

Hafez, S. (2004). The Divan of Hafez. Trans. D. Newman. London: Routledge.

Grant, G. (Trans.). (2004). Sri Guru Granth Sahib. New Delhi: Guru Granth Sahib Academy.

Klostermaier, K. (2007). A survey of Hinduism (3rd ed.). New York: State University of New York Press.

Madhav, R. (2024). The Hindutva Paradigm. Westland Publications Limited

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

Thapar, R. (2013). The past before us: Historical traditions of early India. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.