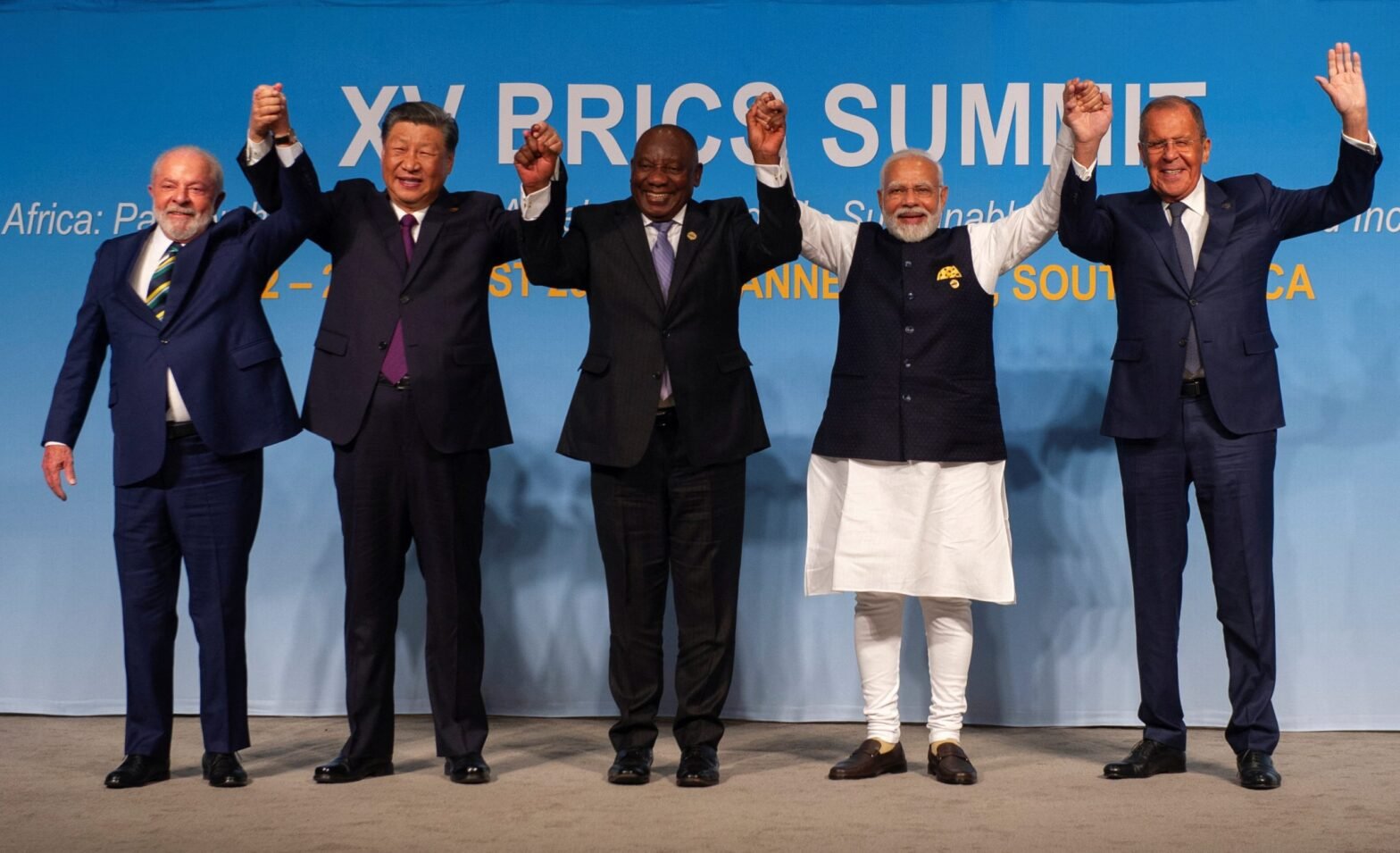

For years, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have been experimenting with the use of their national currencies in trade and agreements within the group and also with other emerging countries. A process of progressive de-dollarisation of their trade and economies is underway, involving now other regions of the world like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) countries and the nations of Mercosur.

In this context, many Western analysts continue to assert that the BRICS coordination has no future, it is doomed to fail. These “experts” should remember that BRICS coordination came into being in connection with and as a response to the Great Global Crisis of 2008, caused by the collapse of the U.S. and international banking and financial systems. The effects were devastating with respect to the production of goods and to world trade. The hardest hit was indeed the poor and developing countries. That is, those who did not bear the responsibility for economic and monetary mismanagement and financial speculation, but who paid a heavy price for the consequences.

All financial data confirm that the global financial situation is today worse than that of 2008. For example, world public debt moved from $41 to $92 trillion; global debt is at $305 trillion, $45 trillion higher than its pre-pandemic level; the mostly unregulated and often speculative Non-Bank Financial Institutions (NBFI) overcame the Banking System globally, etc.

Therefore, despite all the legitimate differing national orientations and sometimes diverging or competing interests of the BRICS countries, the necessity to have a safety net and of crafting an alternative to the likely crisis of the dollar and related systems remains stronger than before.

Multilateralism and the challenge of a new international financial order

Multilateralism is today the only means of peacefully addressing and resolving the many global challenges, political, economic, monetary, and even those concerning security. It is a concept recognized in Europe as well. Among others, François Villeroy de Galhau, the governor of the Banque de France argued this during the May 2022 Emerging Market Forum in Paris in a speech on “Multipolarity and the role of the euro in the International Financial System.” He stated that “while Bretton Woods disappeared when the convertibility of the dollar into gold failed, the international monetary system remained based on the U.S. dollar. The idea of a global currency has not thrived in academic debates, much less in policy discussions.”

Even as early as the 1960s, Henry Fowler, the Treasury secretary under President Lyndon Johnson, warned that “providing reserves and trade to the whole world is too much for one country and one currency to bear.”

The idea of change had been taken up in 2010 by Michel Camdessus, longtime managing director of the IMF, who had launched an initiative to highlight the shortcomings of the international financial system, particularly its global governance and over-reliance on a single currency.

This debate is also very intense in the United States, even if ignored by most of the media. For example, a leading American economist, James K. Galbraith, asked the question: “Can the United States survive the rise of a multipolar world?”

Galbraith is an economics professor at the University of Austin in Texas, best known for drafting the first legislative plan to save New York City from bankruptcy in 1975. He is the son of John Kenneth Galbraith, a famous economist and a close associate of various American presidents, starting with F. D. Roosevelt, for whom he implemented the price control policy during the Second World War.

To the question above, formulated in his article published by the Institute for New Economic Thinking, James Galbraith answers positively but adds, «not without a political upheaval, stimulated by inflation and recession and by a declining stock market in the short term and, finally, by demands for a realistic strategy in tune with the current global balance of power». He says that “the dollar-based order has thus far been sustained mainly by instability elsewhere and the lack of a credible alternative.”

He expects China to work to “set up bilateral or multilateral payment mechanisms, with willing partners, that bypass the conventional medium of the dollar.” However, it will be inevitable that the question of an alternative to dollar reserves will be raised. In addition to the role of gold, “an international financial asset will emerge, composed of a weighted set of securities of the participating countries, similar to Eurobonds … In the reality of Eurasia, this means a bond based predominantly on the Chinese currency.”

His prediction is that “the dollar-based financial system, with the euro serving as a junior partner, is likely to survive, for now.” A significant no-dollar, no-euro zone could be created, cut out for those countries that the US and the EU consider adversaries, primarily Russia, and for their commercial partners. China will act as a bridge between the two systems: it will be the fixed point of multipolarity. “If tough decisions are to be made against China, then a real division of the world into isolated blocs, as in the Cold War, would become a possibility.”, he says.

The role of national currencies in trade

China is clearly at the forefront of using its currency, the renminbi, for its international trade and investment. The most resounding agreement was the one signed in 2018 in renminbi and rubles for the supply of Russian gas to China for the equivalent of about $400 billion. It should be kept in mind that it imports $250 billion worth of oil and another $150 billion worth of commodities such as steel, copper, coal, and soybeans from the rest of the world every year. All these commodities are today valued and traded internationally in dollars. Therefore, China also has to pay for them in U.S. currency. The use of the renminbi, therefore, has become a strategic priority for Beijing. Trade in the renminbi is intensively done with the other BRICS countries but more in general with the other emerging economies worldwide.

China and Saudi Arabia, for example, in addition to oil agreements, recently signed a memorandum to coordinate the economic initiatives of the Belt and Road Initiative with the Saudi “Vision 2030” program of industrial and manufacturing development. The agreements include cooperation in space, nuclear, missile, new energy such as hydrogen, and major infrastructure including the construction of “Neom,” a $500 billion super modern city. Among the contracts signed is one with Huawei, the telecommunications giant, which, despite U.S. opposition, already has 5G network agreements with almost all Gulf countries. The prospect, of course, is to bring BRI with all its infrastructure, technology and industrial projects to that region and on to the Mediterranean. China has naturally proposed to use the renminbi in payments for energy supplies and more generally for trade.

Another example is Egypt, which applied to join the BRICS in 2022, and is reportedly considering issuing renminbi-denominated bonds for the Chinese market. Beijing has already signed currency swap agreements with more than 30 countries, including Japan and Russia, allowing the renminbi to be used for certain trades. Many cooperation projects between Brazil and China are already financed and settled in the Chinese currency and in the Brazilian real. In 2019, Russia and China signed an agreement to use ruble and renminbi financial instruments to cover 50 percent of all their bilateral trade in the coming years. The implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the financing role of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank help to internationalise the renminbi.

Many infrastructure projects with the Asian countries involved are already contracted in the Chinese currency. More surprising is the renminbi deal between China’s National Offshore Oil Company and France’s Total Energies on 65,000 tons of liquefied natural gas imported from the United Arab Emirates. The deal is being handled through the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange; an exchange created to facilitate renminbi payments.

India likewise has been preparing its currency, the rupee, to play an important role in international markets for quite some time. According to Indian policy experts, “sanctions have created a new world of countries seeking to trade using their own currencies instead of the U.S. dollar.” They also claim that sanctions have harmed third countries, such as India, which are only guilty of having trade relations with those who, for a variety of reasons, have been subjected to sanctions. For example, Venezuela and Iran are rich in oil and have been India’s major crude suppliers in the past. Trade was effectively stopped because of U.S. sanctions. Myanmar has also been subjected to several sanctions, tightened after the latest military takeover. Indian trade has also paid the price. India argues that the Western sanctions policy will remain in place for a long time and that other countries may be targeted in the future. This fear is prompting policy makers to set up alternative payment systems. The goal is to create parallel systems that can enable trade, rather than immediately “replace” the dollar.

The Indian reflection starts with energy. It states that the global energy scenario has changed over the past two decades. After the growing role of the Chinese renminbi, which has emerged as an alternative to the dollar, New Delhi wonders whether the rupee can be a third player with a petro-rupee. As is well known, India is the world’s third-largest consumer and second-largest importer of energy. Indians complain that the world oil and gas trade is conducted almost entirely in dollars on Western exchanges and with prices that do not represent real demand. India argues that the 2008 crisis challenged the dollar’s role as the single global currency and that its instability would double U.S. debt, prompting Washington to retreat from globalisation processes. It is noted that unilateral and geopolitically motivated sanctions have aroused strong resentment toward U.S arbitrariness. Hence the move to internationalise the rupee through the creation of a hub for a new international oil and gas market, possibly linked to the Mumbai exchanges. In this way, the Indian government could bring its influence to bear on energy price formation.

The proposal of a new currency

From the standpoint of the already long experience of the use of national currencies and looking at the future perspectives for stronger institutional cooperation, discussions and proposals about a new BRICS currency are legitimate. I do not believe that such a common currency is a factual possibility in the near future, but the studies upon this are today urgently needed.

Russia has been at the forefront of this idea. In mid-March 2022 a meeting dedicated to the “New phase of monetary, financial and economic cooperation between the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and the People’s Republic of China” was held in Armenia, under the auspices of the Eurasian Economic Commission and of Renmin University of Beijing, to define the contours of a new international monetary and financial system, at least as regards the Eastern part of the world.

The EEU is the economic and commercial union in which Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia participate, with a GDP of approximately 1,700 billion dollars. It means to establish a close collaboration with the Belt and Road Initiative, the new Silk Road charted by China. Already in 2020, China had increased its trade turnover with the EEU by about 20%, while national currencies of the concerned states accounted for only 15% of total trade.

What was on the table at the conference was precisely the creation of a “new currency” based on a basket of currencies, among them the ruble and the yuan, also anchored to the value of some strategic raw materials, including gold.

To think that it is just a desperate reaction to the recent imposition of super sanctions on Russia would be a misleading assessment. Instead, it is a project that has been in the field for many, many years, both in Russia and in China.

The project was made public as early as October 2020 by Russian economist Sergey Glazyev, a member of the Council and minister in charge of Integration and Macroeconomics of the Eurasian Economic Commission. He had proposed creating new national payment instruments to set aside the use of “third country currencies”, obviously meaning above all the dollar and the euro, in commercial and monetary transactions between members of the Eurasian Union and China.

Glazyev stated that the idea was the response “to the common challenges and risks associated with the global economic slowdown and the restrictive measures against EEU states and China”. The Russian economist argued that the financial and payment infrastructure was already in place and it was necessary to develop a system of incentives to encourage its use in trade and economic relations.

The minister of the Eurasian Economic Commission proposed: 1) to develop mechanisms to stabilise the exchange rates of the national currencies of the member countries, reducing bank commissions and interest on loans; 2) to create mechanisms to determine the prices of goods in national currencies within the framework of the agreements between the EU and the Belt and Road Initiative, subsequently also involving other countries, possibly those of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and those of the ASEAN.

Furthermore, in an interview on April 14, 2022, with The Cradle, the online journal of geopolitical analysis, Sergey Glazyev recalled that, together with economists from the Astana Economic Forum, a decade earlier he had proposed moving towards a new global economic system based on a new trade currency pegged to an index of the currencies of the participating countries.

It was then proposed to expand the underlying currency basket by adding some exchange-traded commodities. A monetary unit based on such a large basket was mathematically modeled, demonstrating a high degree of resilience and stability.

In the first phase of the monetary transition, these countries would use their own national currencies and related clearing mechanisms, supported by bilateral currency swaps. Price formation would still be guided by prices determined on various exchanges and denominated in dollars.

This stage, according to Glazyev, was almost complete. After Russia’s reserves in dollars, euros, pounds and yen were “frozen,” the Russian economist said it would be unlikely that any sovereign country would continue to build up reserves in these currencies, instead it would seek to replace them with other national currencies and gold.

The second phase should include new pricing mechanisms that would no longer refer to the dollar. Pricing in national currencies would incur overhead costs, but it would still be more attractive than current pricing in “pegged” currencies, such as dollars, pounds, euros, and yen. The only remaining global currency candidate, the Yuan, would not take their place due to its inconvertibility and limited external access to China’s capital markets.

The third and final phase of the transition to the new economic order would involve the creation of a new digital payment currency.

As can be seen, according to Glazyev this new currency would be open to BRICS and other interested countries. In my opinion, this is an interesting idea but not a practical one. A preparatory middle step is needed, first in the form of a unit of account.

The example of the ECU

The European currency unit, ECU, indicates the unit of account established in March 1979 within the European Monetary System (EMS), whose structure was defined as a basket made up of specific amounts of each community currency, weighted according to the importance of national economies, in terms of gross domestic product and intra-community trade.

The ECU was not a circulating currency and did not replace the value of the currencies of European Economic Community (EEC) member countries. A unit of account is one of the functions of money. It is a measure, a standard numerical monetary unit of measurement of the market value of goods, services, and other transactions. Therefore, it is a necessary prerequisite in commercial agreements that involve debt.

Using a mechanism known as the “snake” the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) tried to minimise fluctuations between member state currencies. It attempted to create a single currency band, pegging the EEC currencies to one another, with the aim to achieve stable, fixed ratios over time, and prepare the ground for the European Single Currency to replace national currencies.

The ECU replaced the European Unit of Account (EUA) which was introduced in 1950 for the European Payment Union. Originally the EUA was defined with the same value of a US dollar. After the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, with the 1971 decoupling of the dollar from gold, the EUA was redefined as a basket of European currencies. In 1974 the EUA basket was designed to have the same value as the IMF Special Drawing Rights basket.

Since the 1980s, the ECU experienced a notable development in its private monetary and financial uses (issue of bonds, bank deposits and credits, travelers’ cheques, etc.) and particularly in the commercial sector as an invoicing and payment currency. With the adoption of the euro on 1 January 1999 by the European Economic and Monetary Union, the ECU ceased to exist. The conversion between ECU and euro was established on the basis of a ratio of 1 to 1.

The ERM and the ECU processes were undermined in 1992 by Margaret Thatcher’s announcement of her outright opposition to the European Economic and Monetary Union. The general economic instability in Europe pave the way for an impressive speculative attack against some currencies, like the British sterling and the Italian lira.

The speculative attack against the sterling became known as the “Black Wednesday” of September 16 1992. The same day the UK government was compelled to withdraw the sterling from the ERM. According to reports the UK spent over £ 6 billion trying to defend the value of the currency. In those days the big financial speculators moved in to kill the ERM. Press reported that George Soros, known as “the man who broke the Bank of England”, made a speculative profit of over £ 1 billion in few days. Later the UK Treasury estimated the cost of Black Wednesday at £3.14 billion. For other people the overall cost to the British economy was much, much higher.

In the same days of September, the Italian lira also became the target of massive international speculation. The entire process was more widely analysed in Italy and was known as the “Britannia Story”. In fact, shortly before the crisis began, at the beginning of July, an informal meeting took place on Queen Elizabeth’s yacht Britannia off the harbor of Civitavecchia, near Rome, involving British and international financial interests and representatives of the companies in which the Italian state had a stake. The discussion was about the privatisation of these companies.

Italy had to face huge costs from the Bank of Italy’s attempts to defend the value of the lira from speculators. More devastating was the effect of the devaluation of the currency following waves of speculative attacks: the privatisation of the state-partly owned companies was carried out over time with a “discount” of about 30%!

The undermining of the ECU and of the ERM was the result of speculation and strong political opposition from dominating Anglo-American power centres. The timetable towards the single currency planned by the European States was upset. European leaders wanted a slower process to be able to combine the monetary union with other fiscal and political unitary decisions. To prevent the collapse of the process to build up the European Union, the monetary transition and the creation of the euro were accelerated. Now, Europe’s structural weaknesses are apparent, due the fact that the single currency and the European Central Bank are not supported by other, common political, economic, social and defence institutions, such as a single ministry of public finance.

The ECU experience could be a very important case study in the process of creating a BRICS unit of account. The technical aspects can be studied and improved. Eventually, some of the European economists who worked with the ECU process can still be consulted.

According to me, the most important lesson to learn is the way ECU was attacked and undermined. I am sure the BRICS leaders are well aware of this danger. It is important, therefore, to prepare a number of strong defensive measures against speculative and other attacks. The BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) has been conceived as a defense mechanism to face situations and threats as experienced in the 2008 global financial crisis. The latter originated in the US financial and banking sectors awash in debts and immersed in speculations, its devastating effects reverberated dramatically in the emerging economies. Along with the creation of a unit of account, the BRICS should modify and improve the CRA in order to be able to support it in case of need.

Another step in the same direction could be the creation of a strong gold reserve inside the New Development Bank as an alternative defence instrument in case some national currencies of BRICS members come under international speculative attack.

Conclusion

On the occasion of the 14th annual BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Summit, dedicated to a “New era of global development”, organised in Beijing at the end of June 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that the member-countries are preparing to create an international reserve currency.

Speaking online at the BRICS Business Forum, he said: “Russia’s financial messaging system is open to connect with banks, thus projecting the need for a BRICS member country reserve currency. The Russian MIR payment system is expanding its presence. We are exploring the possibility of creating an international reserve currency based on the BRICS basket of currencies.’

After the sanctions imposed by the West against Russia following the war in Ukraine, it is an almost inevitable move, expected by those who analyse political processes with a scientific and realistic approach, without ideological bias or prejudice.

Among the various sanction, in addition to the freeze of more than 300 billion dollars of monetary reserves of the Central Bank, Russian banks have been excluded from the SWIFT system of international payments. However, there are other global bilateral or multilateral settlement systems for cross-border financial services, such as the Chinese CIPS system. CIPS processed about 80 trillion yuan ($11.91 trillion) in 2021, an increase of more than 75% year-on-year. According to SWIFT data, the yuan maintained its position as the fifth most active currency for global payments, with a share of 2.14% of the total.

In the context of the present growing global conflicts, it is legitimate from the side of BRICS countries to prepare and alternative separate monetary system, but I believe that inevitably the emergence of two counterpoised systems, a Western one and an Easter-Southern one, would increase the danger of a direct confrontation.

On these matters, I share the evaluation of Villeroy de Galhau, already mentioned above. He acknowledged that a fragmented financial system poses a serious danger. We must avoid moving from a dollar-dominated system to a conflictual non-system between the dollar world and, for example, the Chinese renminbi world. This would generate instability, with the risk of competitive currency devaluations. It could lead to the development of separate payment systems with limited interoperability and weaken the global financial safety net. In particular, he noted that to avoid the mistakes of the past, we would need to generate a collective momentum toward a stable, market-oriented multipolar financial system.

Indeed, on the basis of a stronger international position and the growing influence in the so-called global South, the BRICS should work to propose and organise a reform of the entire international monetary system based on a basket of currencies, involving also the dollar and the euro.

Unfortunately, in the context of the war in Ukraine, the European Union is behaving as as junior partner of NATO. Nonetheless, it should be remembered that the economic reality and the genuine interests of Europe demand a more autonomous and independent strategic and geopolitical orientation. In my opinion, it is of utmost importance that the BRICS group, which has proven to be realistic and responsible hitherto, work for alternative global monetary and financial reform in collaboration with those in Europe, and also in the USA, who are committed to a peaceful future based on global justice and cooperation.

Author Brief Bio: Paolo RAIMONDI is an Economist; Columnist for the newspaper “ItaliaOggi”; and Expert member, Eurispes BRICS Lab.

References:

https://www.reuters.com/markets/global-public-debt-hits-record-92-trillion-un-report-2023-07-12/

https://www.iif.com/Products/Global-Debt-Monitor

https://www.fsb.org/2022/12/global-monitoring-report-on-non-bank-financial-intermediation-2022/

François Villeroy de Galhau, https://www.bis.org/review/r220517b.pdf

Henry Fowler, see IMF Summary Proceedings Annual Meeting 1965 9781475565157-9781475565157.pdf

https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-imf-idUKTRE5AG1EV20091117

James K. Galbraith, https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/the-dollar-system-in-a-multi-polar-world

On the Yerevan meeting, see https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/prove-generali-di-monete-rivali-34394 e https://kapital.kz/finance/103768/yeaes-i-knr-razrabotayut-proyekt-mezhdunarodnoy-finsistemy.html “EAEU and China will develop a draft international financial system”

Sergey Glazyev 2020. See various interventions in http://www.eurasiancommission.org/en

Glazyev’s interview with The Cradle https://thecradle.co/Article/interviews/9135

ECU,https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statisticsexplained/index.php?title=Glossary:European_currency_unit

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/black-wednesday.asp

President Vladimir Putin: “Greetings to BRICS Business Forum participants June 22, 2022”

http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/68689

www.brics-info.org Brics information Sharing & Exchanging Platform for all the information and speeches,

www.brics.utoronto.ca for all the final declarations and other official papers.

Vedi www.ndb.int for the New Development Bank

BRICS Foreign Ministers meeting, final declaration and speeches http://brics2022.mfa.gov.cn/eng/hywj/ODMM