The economic development of India is shouldered by its industries. Since the early days of modern India, industrial policymaking has almost always concentrated on the upliftment and the augmentation of agriculture and industry. Empirical data shows that the manufacturing sector contributes to almost 29.73% to India’s GDP. The Indian State, in the early days of freedom, faced severe illiteracy, poverty, low per capita income, industrial backwardness, and unemployment. Resultantly, policymakers strived to incubate a climate for industrial development. The first industrial policy introduction (1948) became a significant part of the first five year plan marked out by India’s founding fathers. The introduction of the industrial policies paved way for breakthrough policy statements to follow (1956, 1973, 1977, and 1980). After what seemed like an indentation in the economic progression of Indian industries for a few decades preceding the 90s – an all-around change was introduced in 1991, in the framework giving a new direction to liberalisation and open markets. There appeared encouraging trends on diverse fronts as a direct result of this move. The industrial growth that was 1.7 per cent in 1991-92 increased to almost 9 per cent within a decade. With the devaluation of the overpriced Rupee, the industrial structure balanced domestic demand with the newfound world market. The impact of the reform was reflected in multiple increases in investments, both domestic and foreign.

It was in such an environment that India woke up to the advent of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Foreign investment brought India closer to the different economies of the world, thereby updating various sectors in India like manufacturing, infrastructure, transport, technology, services, productivity, hospitality etc, to their external counterparts. Global trade and foreign investment make for great parameters to determine India’s global openness. Without a global presence, the Indian economy like any other would have perished under the boulders of market forces. With the times, FDI has taken on various mantles to facilitate international trade and finance. This article aims to analyse the role of FDI in India’s journey towards the new tomorrow, with revised industrial aspirations, and refined industrial production means.

Prologue: Globalisation in Industrial Development

Industrial Policy of Investment as an instrument has perpetually been perceived in dichotomy. While one section champions it as a means of rapid economic growth and development (cite East Asian economies), others condemn its import-substitution policy failures (cite sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America). But what cannot be forsaken is the idea that industrial policies of investment is responsible for resource transfer on a transnational basis. FDI generates externalities in the form of technology transfer through various rates of spill-overs on the productivity of domestic firms (Liu, 2006). A new theory to have emerged in this context is that the level and rate effects of spill-overs can go in opposite directions. While the negative level effect highlights the costliness of technology transfer, iterating that scarce resources must be devoted to learning, the positive rate effect proposes technology spill-overs behind enhanced domestic productive capacity. What cannot be missed in this context is that industrial policy finds itself as a primary apparatus for economic development in the global setting. Notwithstanding the inescapable market failures, internationalised industrialisation in India is perceived to be necessary—the approach being a smooth amalgamation of private participation and state intervention.

The side proposing structural industrial policies houses arguments that allow governments precedence to manoeuvre policy routes, despite with the presence of private stakeholders. In this view, economic development is founded by the country’s endowment structure, in terms of its relative abundance of labour, capital, and natural resources. Now the industrial construction of India is endogenous to this endowment; changing the endowment correspondingly alters the industrial policy. The policymaking is also rooted in the operational mechanics of the private sector, which responds effectively to prices reflecting the relative abundance of scarcity of its own set of factor endowments (Justin Lin, 2012). In India therefore, the government pursues economic development in collective effort with the corporates, facilitating entry of firms into industries with the country’s latent comparative advantages. In a side-track, the Indian markets absorb the large externalities that might be later engaged for infrastructural upgradations and improvements. The government’s role here is to ensure the launch the economy in the process of said upgrading.

There is however a flip side to it. The side opposing the structural industrial policy put the full onus on the government. Unlike their peers, this section does not assume that there is or will be a private sector mature enough to respond to the coordinated activities between and with the state.

Contrasted to Lin’s approach of assuming the production factors to be allocated to a country’s comparative advantages, Ha Joon Chang (Lin and Chang, 2009: 490–91) shows many poor countries to exhibit limited factor mobility and access to technology, thereby impeding industrial upgrading efforts.

This side of the policy debate asserts a pronounced role of the government in overcoming the many complications to industrial upgrading. Less affluent countries such as Angola and Mozambique are likely to face structural hindrances owing to their low endowment levels that the coordinating method may not be equipped to handle. This might mangle the industrial upgrades, making it impossible for the countries to follow market signals. As a result, Chang fears that the country risks entering an industry its endowment level cannot afford, thereby defeating the aim to smoothly plug into the comparative-advantage-conforming strategy.

As divergent as these two sections of the policy debate may appear, they share a bit of common ground is acknowledging the importance of industrial upgrades for economic development, and the government’s substantial role in the process. Now, how far the regulatory easements might be tolerated by a government depends on the target industry, as well as the country. Restrictions, for instance, remain common in a specific stage of the procedure – entry regulations for infrastructure industries have remained restrictive1 owing to new screening procedures developed by the NIR-driven models (New Industrial Revolution, as I discuss later). More generally, most measures adopted over the past decade have considerably relaxed restrictions. Manufacturing has hardly faced the brunt of regulation, with more than 95 per cent economies allowing full foreign ownership of facilities.

Today, with as much as 80 per cent of industrial policy measures taken since 2010 abolishing FDI limits, the point of initiation of a resolve to this dichotomy has been found. The broad openness to foreign investment in industrial sectors in most countries is the result of an ongoing trend to relax formal FDI restrictions. This sense of responsible investment policy in industrialisation, without undermining the presence of the government, is allied to the idea of the structural industrial policy. For example, India in 2015 had adopted a comprehensive FDI liberalisation strategy and relaxed FDI rules in 15 major sectors, including manufacturing. In a way, Indian policymaking has struck a balance between laissez faire and regulation.

Academia has churned out a considerable amount of literature on this over the decades, emphasising on this middle path to be taken. Economics submits a host of literature championing FDI as a growth performance enhancer for the host country. However, there is a lacuna of unanimous agreements among empiricists about positive impacts of FDI on Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In fact, studies by Konings (2001), Damijan et al. (2001), Zanfei (2002a, 2002b) and Zukowska-Gagemann (2002), found a negative relationship between these two variables. While there are opinions advocating both sides, I seek rationale behind the operational mechanics of FDI in the search for a reason behind the positive (or the negative) relationship between GDP and FDI and Mello’s (1990) findings on FDI’s role in growth simulation. He states that FDI simulates growth through i) capital spill-overs by encouraging the adoption of new technology in the production process, and ii) stimulating knowledge transfers by bringing in alternative management practices in place.Both Mello and OECD, in another study, stress on the host country’s attainment of a certain degree of development in education and/or infrastructure before being able to enjoy the results of FDI. Alternatively, the host has to settle for a weak or an insignificant impact on economic growth

Several studies have discussed the conditions necessary for identifying FDI’s positive impact on economic growth, each accentuating on different closely related aspects of development. It is comprehensible therefore, that there exists a relationship between a country’s developmental aspirations and foreign investment. This analysis focuses exclusively on the industrial connotations of foreign investment, especially how investment policy is fundamental to the overarching industrial policy.

An often overlooked aspect of FDI is also one of the most important: upgrading current industrial infrastructure. With the flow that FDI ensures, the government has a choice to distribute the resources into industrial factions for optimal upgrading. It is however, recommended for governments to concentrate activities that are in their nascent stages more than those already well-established (Rodrik, 2004). In economics, this is also referred to as the new technology (or a new good/service). As a nod to Ha Joon Chang’s conclusion, policymaking in India must tread farther from its comparative advantages (agricultural trade and agribusiness) towards the endorsements of new ways of producing (manufacturing sector)2 . In this relation, Indian institutions need to further learning in the economy to upgrade the end that ties the slackest knot.

Unlike allocating resources to a comparatively advantageous section, upgrading current infrastructure is nuanced in nascent industries. It is not like India is not in pursuance of excellence, but today industrial policy warrants ideas out of the convention. Weiss (2011) offers a broad perception to utilise FDI in ensuring industrial upgrading:

1. Micro economy: A collaboration between the governance and the local industries for

A. Identification and alleviation of constraints to industrial upgrading;

B. Establishment of public-private “deliberation councils” to identify roadblocks and propound solutions to upgrading;

C. Creation of centralised budgets for allowing public institutions to draw on state resources (Hausmann et al., 2008: 5–10).

2. Macroeconomy: A government can promote upgrading through, for instance, making credit available for risk-taking ventures as well as choosing to focus on promoting a priority sector instead of an industry. Enhancing efficiency for these promoted sectors however need to be time-bound, be transparent, and have clear performance criterion.

Amidst a multitude of interventions that are deemed necessary by aforementioned literature, a distinguished characteristic of a new industrial policy has been called for. There is now a need to harness a country’s potential for capacity-building, promote Higher Value Additions (HVA activities) in the economy and therefore participate in and capture the gains of higher levels of Global Value Chains (GVC)3 . It marks a significant departure from literature discussing an FDI-GDP relationship unilaterally.

Another idea that it successfully defeats is that of the conventional policy forms that advocated protectionism. Such policies have met limited success in achieving industrial perfections, primarily by substituting foreign trade and investments by half-baked scarce levels of domestic demand and investment. A successful global integration is key to realising positive developmental effects in any country (sufficient condition). Yet it also stands, a successful integration is by no means solely dependent on FDI levels (necessary condition), but rather an assortment of quality FDI, good governance, and the ability of the county’s investors to responsibly promote industrial boost.

The need for and the shape of the New Industrial Policy

The temporal journey of industrial policymaking has been through several phases and models, with the deployed instruments evolving along the way. While more “primitive” policies of import substitution restricted foreign investment, those export oriented engaged in measures to maximise positive spill-overs (Zhan, 2011). For certain specific industries currently, almost as much as 40 per cent industrial strategies are vertical. From the remaining rest, a bit over 33 per cent focuses on the more recent horizontal investment facilitation, whereas over 25% on NIR. Other measures to garner incoming FDI – like investor targeting – have also become more prominent4 .

1. Box 01

UNCTAD’s global survey of industrial policy shows for at least 84 countries comprising of about 90 per cent of global GDP to have formalised an industrial policy for their respective selves over the past half-decade alone. Investment policies accommodate for several model prescriptions—the New Industrial Revolution (NIR) especially is a prospect for the world, and especially Indian industrial development. After three previous stages of Industrial Revolutions marked by steam-powered mechanical manufacturing (IR1), electrically powered mass production (IR2), and automated IT-controlled systems (IR3), the NIR heralds the flag for IR4 based on Big Data, cloud-computing, and cyber systems. Based on digitalisation of supply chain technologies, the NIR is changing the way we perceive cross-border investment patterns. India has seized the opportunity to join the bandwagon, specifically with the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution in Maharashtra. The Indian efforts started taking shape with the steps to become an e-government (introduction of biometric demographic database). The government closely works with leaders from business, academia, start-ups and international organisations to co-design new policy frameworks and protocols for emerging technology. India’s aspirations to become a technological power and an AI hub has been reflected on the Global Innovative Index, where the subcontinent currently ranks 52 out of 1255 .

The NIR affects key decisions for productivity boosts, transparency in operations, and reducing inefficiency. Questions like ‘whether to invest,’ ‘where to invest,’ or ‘investment in what capacity’ can be addressed through smartly made strategies. For instance, the choice of location for an investment has become more flexible in the wake of new technologies such as 3d printing and M2M (machine-to-machine). Economics therefore gets modified when decision-making no longer solely rests on conventional variables like labour costs, skill distribution, infrastructure or policy environment. The NIR is also likely to affect investor behaviour in host countries, affecting the readiness of firms to strategise production styles (regional mass production, distributed manufacturing, etc.), data-sharing, training, as well as the relative foot-looseness of operations.

This paper claimed that investment policy is fundamental to an industrial policy. For India’s impetus towards NIR, FDI is more than a stimulant to economic growth. The idea of investment in Indian market encompasses a host of assets that include long-term capital and technology (skills, know-how, physical capital, etc.). These are crucial for industrial development because they are the harbingers of how well a market is doing – availability of scarce financial resources, employment levels, export capacities; skill distribution and transfer, and fiscal revenue levels. FDI here can support the industrial proliferation and upgrading (capacity building). On a global level, this can also imply a connection between a global supplier and a local enterprise through linkages, subsequently leading to the latter’s financial strengthening. So the characteristic of investment policy is ingrained in the measures that in confluence comprise industrial policies.

Today, the stage has been set for innovative industrial policies more out of necessity than convenience. With the change in production processes and reliance on conventional production factors, the entire market for industrial manufacture has transformed. The foremost reason is very obvious – price alterations to suit market necessities. But that also means that there appear economic agents, who incur losses as well as those who profiteer. Market directions in the wake of this new era require updating the existent industrial policies.

A. According to the business cycle, a global financial crisis might be followed by a reduced unemployment and stimulated growth. Governments therefore are more proactive to address negative effects of globalisation.

B. Industry-friendly policies to counter deindustrialisation and opportunity loss of developing countries (both emerging and mature markets) are being deliberated on.

C. Intensified trade competition from East and South-East Asia has pressurised the developed nations, and inspired the low and middle-income countries to ensure greater participation in Global Value Chains (GVC).

D. Through concomitant supportive policies and facilitating regimes, more is being focussed on GVC in the hope of capacity building in the secondary sector.

E. Commitment to the Sustainable Development Goal is to be honoured.

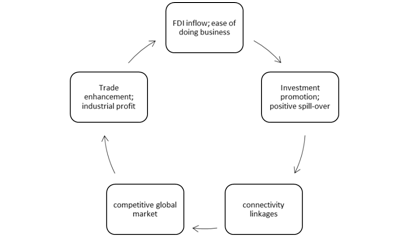

Foreign investment promotion maximises positive spill-overs for domestic industrial development. In a globalised market, foreign ownership limitations or joint venture projects are not uncommon. Joint ventures in particular fosters domestic industrial enhancement and protect key industries from a wholesome foreign takeover. With ease of doing business, also comes stipulations of investment promotion measures and incentivises facilitation approaches. Spill-overs therefrom have capabilities to turn this process into a virtuous cycle of giving (Fig. 01)

1. Fig. 01

Broadly speaking, investment policy is ingrained in a host of closely interlinked policy areas, including trade, competition, tax, intellectual property, labour and other policies6 . Take for example the following policies from India:

• National Policy on Skill Development

• National Policy on Universal Electronic Accessibility

• National Manufacturing Policy

• Science, Technology & Innovation Policy (2013)

• National Policy for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (2015)

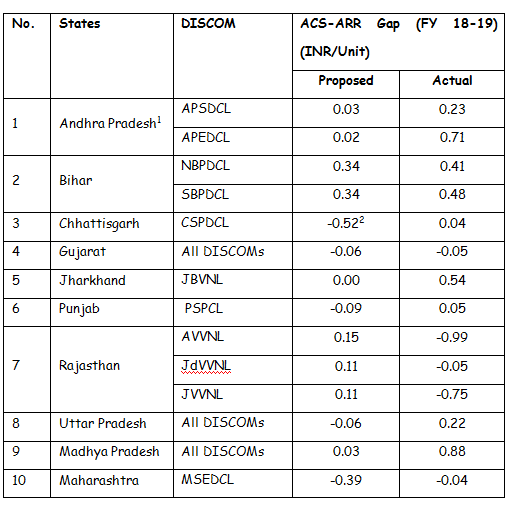

• National Steel Policy (2017)

Investment policy in India recorded post 2010 are directed mostly at the industrial policy purpose. While manufacturing plays a front-running role in the new Industrial policy now, complementary services and industrial infrastructure serve an incentivised and performance oriented purpose. Why India actively chooses an investment heavy route to growth-based development is explained by examining the goal at the end of said route – FDI. In line with industrial policy models, some of the measures that promote direct investments are:

• SEZs – Establishment and endorsement of Special Economic Zones – specialised high-tech zones as the Electronic City in Bangalore, that reflect economic strengths in specific industries or activities (e.g. business process outsourcing). Incubator zones comprising of aerospace and biotech parks have been developed in places like Bangalore or Hyderabad to create a competitive advantage in new industries.

• Investor facilitation (Creation of an investment-friendly environment – for instance, the Invest India Initiative provides the necessary facilitation services for attracting investments into the critical sectors of the economy. Using a host of nodal offices across the government, the ‘cell’ interacts with states in a Hub & Spoke Model to feed the State policies on land, labor and capital to the investor)

• Investor targeting (Utilising existing resources to attract high-end investments)

• Screening and Monitoring

Depending upon the requirements, SEZs can be and have been used for various forms of activities – of course depending on the industrial structure of the country. In India, SEZs serve to not only alleviate high poverty levels, but also are used a part of the broader economic reforms. SEZ is predominantly used in part for economic purposes should be able to diversify exports while keeping barriers in place, and partially as a laboratory to experiment with new ideas. For instance, China had its FDI, land, legal and labour policies tested at its largest SEZs, being extended to the rest of the economy. Indian SEZs often facilitate rapid transfer of good for cheap, offering commute linkages for connectivity, aid investors meet sustainability target (form of incubation), assistance with labour disputes, and environmental compliance issues.

On the other hand, Industrial policies can also selectively restrict FDI through screening. The screening and monitoring procedures in foreign investment can primarily be classified into three broad categories, on the basis of some flexibly defined review criteria (general criteria), and on the basis of the sectoral sensitivities. For the first case, the flexible broad criteria are more often directly related to the national and international interests of the respective countries. Although manufacturing is rarely included in such reviews, sectors of security, labour, society (interest), net benefit, and environment feature mostly commonly across nations. The second case on the other hand, not only provides predictability for a certain investor (knowing well the policies of the respective country), but also ensures that the inspection procedures are carefully followed. Screenings based on sector specific sensitivities might include any sector of the host country that it deems mandatory to be under strict governmental supervision. For instance, the Indian Brownfield Projects in pharmaceuticals is a classic example of sectoral sensitivity, where the entire screening criteria is governed by the statutory act of the Foreign Exchange Management Regulations (2017).

Adding trivia to sector-based restrictions of FDI – much of it has been done keeping in mind the purpose of protecting smaller indigenous businesses, which would otherwise have been crippled by strong international market forces. Such screenings have an unintended consequence of fettering the economy down, thereby keeping it away from harbouring a market economy. The result is the lack of a foreign-local corporate linkage structure in large segments (capacity building).

Being one of the fastest growing nations of the world, India has a balanced amalgamation of giant home-grown corporates and the striving infant industries. In the post-independence era, India has championed protectionist policies to foster these infant industries and provide them equal ground to compete with external competition. This and a handful of sociocultural reasons might have pushed Indian policymakers to pursue restrictive FDI policy. In the present however, this relatively narrow policy scope has given way to a broader approach of strengthening FDI-related instruments. As opposed to the blatant protectionist ideology previously upheld, the current change emboldens approvals for direct and portfolio investments into Indian markets. The beneficiaries of government protection still include national champions, strategic enterprises and critical infrastructure. Moreover, the government finds reason in protection of ailing domestic industries in times of financial crises or to restrict outward investment in order to keep the national employment rate stable. Therefore, the archaic policies that justified FDI restrictions have blurred over time, having been replaced by policies that protect and invite internationalisation of Indian markets without compromising the intervention scope of State in the domestic sectors. In this context, even the Indian markets are being invested on – strengthening the government to better govern the industrial home-grounds. The role of instruments that improve the flow of FDI and provide greater stability becomes an important aspect of industrial policy.

It can be conclusively said that dependence of new industrial policy on investment policy is a key aspect in determining the fabric of the economy. Policymakers can invoke a vast body of economic research on the potential contribution of FDI in industrial development over the years, as well as the former’s effect on investor behaviour. The latest phase witnesses the NIR – the driver of the emerging sustainable and inclusive development – being motivated by investment choices. But the opposite might just as well be true – the NIR’s operations may very well alter the current logical nexus between investment and industrial policies.

India’s path to Industrial Modernisation

A. Investment in Indian Industries

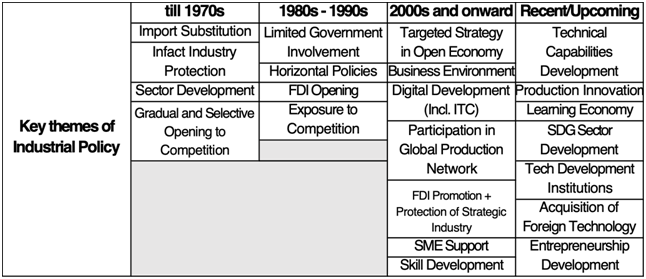

Industrial Policy is essentially a modern phenomenon – as the evolution in industrial policies and new themes revolutionised the way we look at the secondary sector, a global change in policymaking was noticed. From the dawn of the 1900s, industrialisation has thrown out myriad opportunities for modernising the economy. Admittedly, India was one country to jump at the opportunity to bring the manufacturing sector into organised policymaking at the earliest opportunity. These policies have historically been diverse and complex, including a multifaceted objective to drive the growth figures.

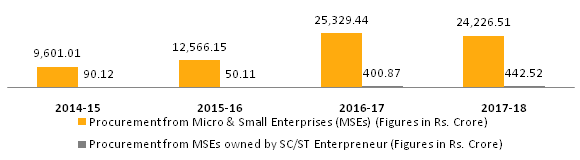

Since FDI has been an important source of funds for companies in an otherwise capital choked country, India effectively juggles market forces and regulations under the governance of the Foreign Exchange Management Act (2000). FDI is automatically routed in most sectors, implying minimal supervision by government. A regular revision is nonetheless done for FDI inflow, through prior approvals and scrutiny of prohibited lists 7. After a string of liberalisation reforms in 2016, applications relating to issues of equity capital import and pre-incorporation costs are managed by DIPP. In the industrial sector (like any other), various categories of investment – portfolio, institutional, venture capital, NRI – can hold stakes in Indian entities if they meet the conditions for the sectoral caps on ownerships. Venture capital has in fact boosted start-ups in sectors of high growth potential in India, often with international funding to promote the NIR-mandated growth of IT.

India thus has become more habitable for FDI over the last few years, owing possibly to a change of regime. After a promise of a more globalised economy and a freer Indian Rupee at the Monterrey Consensus, the vision of the country is to shift gears toward the corporate. The reorientation reflects an increasing realisation that private international capital flows are likely to develop finance to boost the industry sector. This is possibly why we discuss more about the modernisation and the empowerment of SEZs, or regarding the dissemination of investment promotion agencies through the promise of incubation.

Analysis of the FDI’s role in the Indian industrial policymaking should answer the question: how does foreign investment capture the idea of new industrial policy. In its recent incarnation, even the Indian industrial policy is driven towards more foreign investment in the hopes to marry it with measures aimed at (i) capacity building in infrastructure and financial systems; (ii) skill development for human capital and technology upgrade for physical capital; (iii) raising internal demand flooding export markets to tackle trade deficit. Instead of focussed investments on one stage and relying on linkage effects for dissemination of resources, such objectives warrant initiatives at all levels of a market economy. India adopts explicit investment strategies such as its Consolidated FDI Policy to attract foreign investment. This policy push enhances domestic capital, technology (for physical capital) and skill (for human capital) to accelerate economic growth. To be specific, the direct investments operates somewhat to the effect of establishing a lasting interest in an enterprise that is nationally resident, additional to the investor.

B. The GVC Factor

A prime engagement for FDI is also the integration of an industry into GVCs. A wider adoption of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in firms across India has provided multiple opportunities to improve productivity and boost capacity building measures. Through this upgrade, the industrial sector is no longer fettered to a singular focus of just manufacturing. Through its GVC participation owing to IT-based outsourcing operations, India’s trade operations is part of the global trade linked to production networks of MNEs (around 80 per cent).

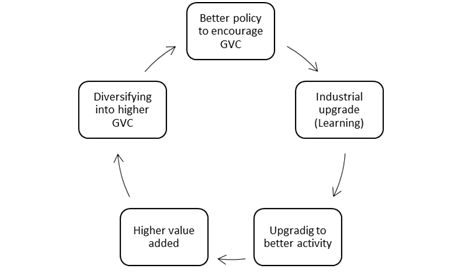

Modernised industrial policy connotes importance to GVC and GVC-led development strategies to encourage export-generation across industry value chains, based on competitive advantages. In focussing on GVC participation, India needs to consistently deliver quality products on time. GVC works on such deliveries being made within the value chain, with a combination of goods and services facilitating it. Therefore, the regulatory mechanisms that India needs to follow must address the increasing significance of private standards in global markets. It technically creates a virtuous cycle:

2. Fig. 02

Indian industrial policies interact closely with (foreign) investment policies. While the former directs on the usage of FDI in the economy, the latter provides the government with the rationale to maintain conduciveness in the markets. Additionally, investment into the Indian economy brings along a set of regulatory instruments – exclusive to each of the money-pots (industries) the FDI has flown to – as well as the endorsement to integrate domestic industries into GVCs and the technological upgrading of the domestic base. In this synergistic operation, the kind of policy tools the country uses is determined by performance requirements. There can be some mandatory requirements (like incentive based proliferation) or voluntary (investment choices based on an industry matrix). Broadly speaking, skilled labour management, trade-related physical capital, proximity to markets, tariff rates, compliance with standards, etc. are some of the many variables that can be had at India’s disposal to formulate said policy tools. Additionally, there is good reason behind GVC being an important factor in the canon of ‘new industry’. Along with the value chain comes facilities such as export promotion, job creation, technology transfer, infrastructure upgrades, etc. Indian development strategies have historically been heavily reliant on industrial pushes, formulated keeping in mind financial support programmes. One of the many such programmes comes in the form of global incentives.

Therefore is it normal to strategise on promoting exports and increase participation in GVCs as an integral part of investment policy? Therein lies a matter of contention for India. Even after being part of the revised ambitions for the new (investment-based) industrial policy, GVC continues to be a developed country story. What we might look at to explain the problem is how the gains are shared, and at what stage. The only countries playing a key role in the forward and backward linkages are the developed economics (US, UK, Japan, etc.). This is possibly because they are the only ones who add more value to other countries’ exports than the value added by countries like China or India in their exports. For instance, China adds a low value to the imported inputs despite having a high participation in GVC. Hence the gains are low on the Chinese end. Owing to GVC, an iPhone of retail price $700 will only have $9 worth of value added in China. The lead firms (Party 1) in the developed end of the GVC integration outsource the lower-value-adding activities to a China or an India, while retaining control over the higher-value-adding areas of core competency. The lead suppliers profiteer out of the fierce competition among numerous participants at the lower end of the integration. What happens with the network suppliers (Party 2) is that they lack specialised skills and readily available physical infrastructure to effectively coordinate value chains. Hence, the higher ends comprising of R&D, Intellectual Property (IP), design and distribution yield more than (let’s say) a final assembly of an iPhone. GVCs invite a discrepancy in market power – a high-VA adding country has the financial authority over a lower-VA adding nation on distribution of gains. As the network suppliers have difficulty accessing technology, inputs, market information and credit, local producers (low-VA end) face hindrances in upgrading their capacity. An Indian producer’s unit price of $20/m, is retailed at 5-6 times in the US markets, the required finance for upgrade will majorly be swallowed by the retailer before reaching the producing unit. Even a bargain is not forthcoming, as a sector with a low entry barrier witnesses high competition. A competitive market increases substitution possibilities in the low-VA end, thereby felling the bargaining power of any one firm. Indian manufacturing sector stands witness to the decreasing barriers to entry – at the same time facing stricter barriers in the branded marketing sector.

However, in an economy where shifting comparative advantage leads to the expulsion of producers from the market, the manufacturing sector in would generate a very low VA in a GVC.

Idea in Industrialisation

The idea of industrialisation is founded on the allied concepts of implementation plans and their accompanying legislatures. The alliance (of plans and legislatures) typically set out horizontal measures 8 supporting the technological upgrades and skill building. Although the classical industrial policy instruments continue to be a part of the toolbox, the newer methods have overwhelmingly taken over – most strategies specifically detail policy objectives to attract investment required for industrial development. In the initial days after the Indian independence, policymaking was based on low level of domestic industrialisation 9 and the need to protect local companies at its early stages. This idea required the environment of the Indian industries to incubate nascent industries or promote temporary tariffs.

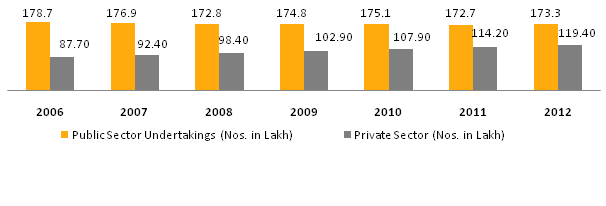

The industrial sector has also stood witness to Public-private partnerships (PPPs) – either purely for financing purposes, or to link public and private research or educational institutions. Such partnerships symbiotically stimulate activity in niches where private investment is reluctant. The rural areas, for example, is a case where PPP is envisaged. Almost 90 per cent of industrial policies strategise private investment, out of which almost 60 per cent is dedicated to FDI promotion.

Conclusion

The economic impetus behind the establishment of the industrial policy the way it has been, is a work in progress for India. As the country steps from strengths to strengths, so does the policy package – the adoption of new technologies in industrial value chains to realise increased productive capabilities.

The content and focus of key policy instruments, including investment policy tools, differ across countries and evolve depending on development paths and objectives. The evidence from the survey of industrial policies of over 100 countries has also shown that they are increasingly multifaceted and complex, addressing myriad new objectives such as participation in GVCs, strategic positioning for the new industrial revolution (NIR) and support for the achievement of the SDGs.

For modern industrial policies to contribute towards a collaborative and sustainable development strategy, they need to be part of an integrated framework. Overall development strategy, industrial policy, macroeconomic policy, trade and investment policies, and social and environmental policies are interdependent and interactive. This requires a holistic and “whole-of-government” approach to mutually reinforce and create synergies among different sets of policies in order to avoid inconsistency and offsetting effects. A crucial condition for successful industrial policies is effective interaction with investment policies, with the aim to create synergies. Countries need to ensure that their investment policy instruments are up-to-date, including by reorienting investment incentives, modernising SEZs, retooling investment promotion and facilitation, and crafting smart foreign investment screening mechanisms. The new industrial revolution, in particular, requires a strategic review of investment policies for industrial development.

Policymakers of foreign investment in any sector of India, must acknowledge the role markets play – a critical role in resource allocation, catalysed by the enabling support from the government against market and system failures. Investment and industrial policies are essentially national-level policy efforts having extensive consequences for the international communities. In the era of the New Industrial Revolution, global integration has compelled the strengthening of regional and multilateral collaboration. Paper exercises on industrial policy deliberations will fail to achieve developmental goals if the practicality of ‘openness’ is not realised. High-level policy formulation, and its effective implementation is ensured by empowered institutions, flexible policy-monitoring, and correction systems built on feedback. For the impetuous run of India’s tall ambitions, an embrace of the global world is deeply necessary.

Biography –

Adri Chakraborty- Adrij Chakraborty is currently working as an Economic Analyst with the University of Mumbai (School of Economics and Public Policy). He is an alumnus of Edinburgh University and his areas of interest are Applied Economics, Labour Economics, Empirics and Econometrics, and Development Studies.

Bibliography

Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development

https://dipp.gov.in/sites/default/files/po-ann3.pdf

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/814101517840592525/pdf/India-development-update-Indias-growth-story.pdf

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/twec.12660

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.633.1092&rep=rep1&type=pdf

https://unctad.org/en/PublicationChapters/diaeia2018d3a1_en.pdf

https://dipp.gov.in/foreign-direct-investment/foreign-direct-investment-policy

Ferole Akinci (2011)

http://www.uh.edu/~bsorense/FDI_Tech_Spill_Over.pdf

https://static.investindia.gov.in/s3fs-public/inline-files/FDI%20Policy%20with%20Amendments_0.pdf

https://www.un.org/ffd/statements/indiaE.htm

https://www.ukibc.com/india-guide/how-india/fdi-restrictions/

http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/GVCs%20-%20INDIA.pdf

https://www.die-gdi.de/uploads/media/OECD_Trade_Policy_Papers_179.pdf

https://www.oecd.org/countries/angola/Participation-Developing-Countries-GVCs-Summary-Paper-April-2015.pdf

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cjas.1455

References:

1 Restrictions are mostly confined to transportation and media inter alia because of their operational sensitivity (Source: World Bank).

2 Balassa’s Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) Index

3 A system of borderless production, where the production processes is fragmented in several stages performed across different countries and connected by services links. GVCs are typically coordinated by transnational corporations (TNCs), with cross‐border trade of production inputs and outputs taking place within their networks of affiliates and contractual partners.

4 New Indian Industrial Policy Directions in Box 01; more themes of industrial policies are included in Box 02

5 GII depends on technological indicators including the incubation for stat-ups, priorities in blockchain systems, and AI

6 More explicit explanations can be found in UNCTAD’s Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development (IPFSD).

7 The automatic route does not require approval from RBI; the Government Route requires prior approval from the concerned Ministries/Departments through the Foreign Investment Facilitation Portal (FIFB), jointly administered by the DIPP and Ministry of Commerce and Industry

8 Economic growth, Job Creation and Competition

9 This was in pursuance with the vertical policies of sectoral development