“Independence isn’t just about international recognition, it’s about internal coherence and the will to remain distinct.”

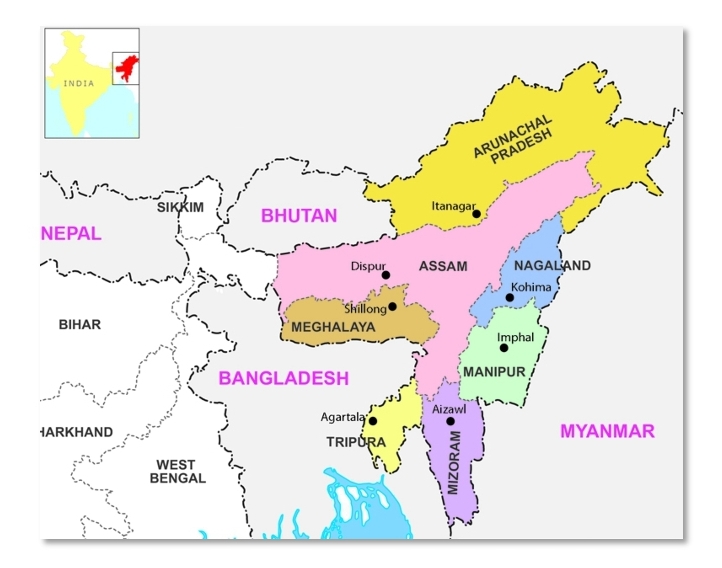

The View from the Roof of the World

When I look at the map of South Asia, my eyes don’t just see the Himalayas. I feel them. I smell the cold, crisp air that bites the lungs at first and then fills you with a strange calm. I hear the crunch of my boots on fresh snow, the faint clang of a prayer bell somewhere up the slope, and the laughter of children chasing a worn-out football along a mountain path. To most, these mountains are a jagged border on paper. To me, they are living, breathing companions, vigilant sentinels who have stood guard over us longer than memory itself.

I have served at these heights, where the clouds drift so low you can touch them, and the stars feel close enough to take in your hand. In Mustang, Nepal, I remember sitting in a tea shop run by the widow of an old Gurkha soldier. She poured my cup with the same steady hands that once fed her husband, and she told me how the mountains keep people honest, how every steep climb reminds you of your smallness. Travelling further to Lomangthang from Mustang, standing in the courtyard of a dzong at dusk, with the walls glowing orange in the setting sun, monks file past in silence. One of them stopped, looked at me for a long moment, and said, “Soldiers stand on both sides.” I’ve never forgotten that.

Nepal and Bhutan aren’t pawns, nor are they“buffer states” between India and China. They’re proud nations, full of grit and grace, shaped by centuries of hardship and joy. Their people have endured earthquakes, blockades, and the slow creep of modern politics, yet they’ve maintained their dignity. They know how to stand with you, and they also know how to walk their path.

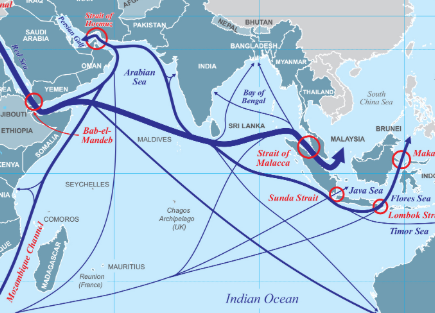

Today, China’s shadow stretches longer over these delicate valleys, and the Siliguri Corridor, our ‘chicken’s neck’, feels more vulnerable than ever. I’ve stood guard there in the monsoon rain, knowing that if trouble ignites in these mountains, the tremor will be felt all the way to Delhi. Out here, strategy isn’t just about maps and troop numbers. It’s about whether the road remains open after a landslide, whether the lone bridge over a roaring river holds, and whether a festival proceeds peacefully.

For me, these lands aren’t just part of a strategic frontier; they’re places where I’ve shared bread, sipped tea, and laughed with strangers who felt like family. And that’s why the stakes here are more than political. They’re personal. Because when you’ve looked into the eyes of the people who live beneath these great mountains, you understand that protecting them isn’t just about securing borders, it’s about keeping a promise.

A Legacy of Geography and Strategy: The Enduring Buffer

When you’ve served in the Himalayas long enough, you realise that geography isn’t just about mountains and rivers; it’s about how those mountains and rivers shape the destiny of nations. Nepal and Bhutan sit right at the centre of it all, not by choice, but through history and terrain. They have always been more than mere dots on a map; they represent the space between two giants, where survival depends on knowing when to advance, when to retreat, and when to stand very still.

Prithvi Narayan Shah of Nepal understood this better than anyone. He called his kingdom a “yam between two boulders”, a perfect way to describe it. You don’t crush a yam unless you squeeze too hard from either side, so Nepal learned to be careful, watching both neighbours and leaning one way or the other when the moment demanded it. Bhutan followed a similar path, only more quietly. Its rulers kept their distance, allowing just enough trade and religious contact with Tibet, but never too much from either India or China.

Then came the British. They regarded Nepal and Bhutan as cushions, buffers, to safeguard their empire from whatever emerged from China. Consequently, they drew lines on maps, signed treaties, and established protectorates. When India gained independence, we didn’t just inherit the land; we inherited that entire mindset. We signed treaties with Bhutan in 1949 and with Nepal in 1950. On paper, these signified friendship and security. In reality, they also implied that we were the safety net; if trouble arose from outside, we would be the ones to respond.

Of course, from Delhi’s perspective, this was logical. From Kathmandu or Thimphu, it sometimes felt like we were acting as the overbearing big brother. I’ve heard it in conversations over tea in mountain towns, that blend of gratitude and quiet resentment. But even with the politics, the arrangement endured. Trade continued, soldiers trained together, and people crossed the borders freely. Beneath it all was an unspoken understanding: if the mountains were ever threatened from the north, India would stand its ground.

Buffer States as Imperial British Strategy

By the 19th century, the British in India understood one thing very clearly: if you want to keep an empire safe, you don’t just defend the borders, you push the danger further out. For them, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, and even Tibet for a while became the outer moat. These weren’t just names on a dispatch from Calcutta; they were the first line of obstacles between the Raj and rival empires—Qing China to the north, Tsarist Russia creeping in from Central Asia.

The British didn’t leave anything to chance. They drew borders, sent out survey teams, signed treaties, and, when necessary, marched in with bayonets. I’ve walked some of those same ridgelines where surveyors and soldiers once stood, looking north toward Tibet and beyond. You can see why they wanted those buffers; the land itself is a fortress if you hold it right.

Nepal, under Prithvi Narayan Shah’s successors, had been expanding rapidly, fighting in Tibet with Chinese backing, and pushing into smaller kingdoms in North India. That kind of momentum worried the British, so when it came to blows in the Anglo-Nepalese Wars, the Raj threw everything it had. The Treaty of Sugauli in 1816 cut Nepal down in size, but here’s the clever bit: the British didn’t dismantle the kingdom. They kept the Shah dynasty in place, knowing Nepal’s mountains and its Gurkha warriors were worth more as allies and buffers than as conquered land.

In the decades that followed, Nepal played a cautious game, paying tribute to China after 1792, but by the late 1800s, it leaned heavily towards Britain. The 1923 treaty between the two formalised this arrangement, clearly signalling to Beijing: Nepal remains independent, and Britain will ensure it. In return, the British provided arms, training, and recognition—precisely the kind of support that enables a small kingdom to stand tall without standing alone.

Bhutan’s story ran parallel, though bloodier in parts. After losing the Duar War in 1865, it relinquished the fertile Duars to the British under the Treaty of Sinchula. The monarchy retained control over domestic affairs, while Britain strengthened its hold on foreign policy, all the while paying an annual subsidy. When Chinese interest in Tibet began to intensify, the British responded once more. The Treaty of Punakha in 1910 guaranteed Bhutan’s internal autonomy but placed its external dealings firmly under British “guidance.” In simple terms, Bhutan could manage its affairs, but when it came to looking beyond the mountains, Britain held the map.

From a soldier’s point of view, it was a neat arrangement: mountains held by friendly forces, enough autonomy to keep the locals invested, and a line of defence well beyond the plains. The Raj may be gone, but you can still feel the shape of that old strategy in the way we look at these borders today.

From Buffer to Protected State: Evolution after Independence

When British rule ended in 1947, the subcontinent’s northern frontier entered a new phase of uncertainty and change. Would the principle of buffer states endure after the Empire’s collapse? For India, maintaining these arrangements seemed both sensible and essential. The memories of Chinese intervention in Tibet and the imperial fear of Russian advances continued to influence Nehruvian foreign policy thinking.

India acted swiftly to secure the Himalayan rimland. In Bhutan, the 1949 Treaty of Peace and Friendship mirrored many aspects of the Punakha system. Bhutan consented to Indian “guidance” in foreign policy and defence, in return for recognition of independence, a promise of non-interference in domestic affairs, and economic aid. The result was to keep Bhutan as a buffer, but now within India’s rather than Britain’s sphere.

Nepal’s status was formalised in the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950, signed on 31 July 1950 in Kathmandu. This treaty reinstated and broadened the open border, provided for mutual defence consultations, and, importantly, permitted unrestricted movement, settlement, and property ownership for citizens of both nations. The context was urgent: Communist China had recently consolidated control over Tibet, and both Delhi and Kathmandu feared its armies could suddenly cross the high passes. India thus aimed to secure a closer alliance with Nepal than ever before, safeguarding its sovereignty while expecting complete strategic loyalty.

The Balance of Dependency and Resentment

“Survival in the Himalayas has always been about reading the winds correctly; some kingdoms learned this lesson better than others.”

China’s brutal takeover of Tibet in the 1950s remains one of the most significant geopolitical upheavals of the modern era. Before 1950, Tibet was a peaceful, largely autonomous buffer between the Indian subcontinent and the Chinese heartland. The People’s Liberation Army’s swift and ruthless military campaign shattered that balance. The so-called “liberation” was, in reality, a calculated annexation characterised by suppression of Tibetan cultural identity, destruction of monastic institutions, and a brutal campaign of political control. By 1959, the flight of the Dalai Lama into India, along with tens of thousands of Tibetan refugees, revealed to the world the true nature of Beijing’s ambitions. What had once been a high-altitude shield for India and the smaller Himalayan kingdoms was now a militarised forward base for Chinese expansionism.

For Nepal and Bhutan, both much smaller in territory, economy, and military capacity, the fall of Tibet served as an existential warning. They had long depended on geography, with towering mountains and difficult passes functioning as a natural defence. Tibet’s absorption by China demonstrated that terrain alone could not guarantee safety against a determined and resource-rich aggressor. In the years following the takeover, Beijing consistently expanded its influence by building roads and airstrips, stationing troops near their borders, and conducting diplomatic campaigns to pull these nations into its sphere of influence. For these small Himalayan states, the shadow of the PLA was no longer a distant concern; it was an immediate and persistent reality.

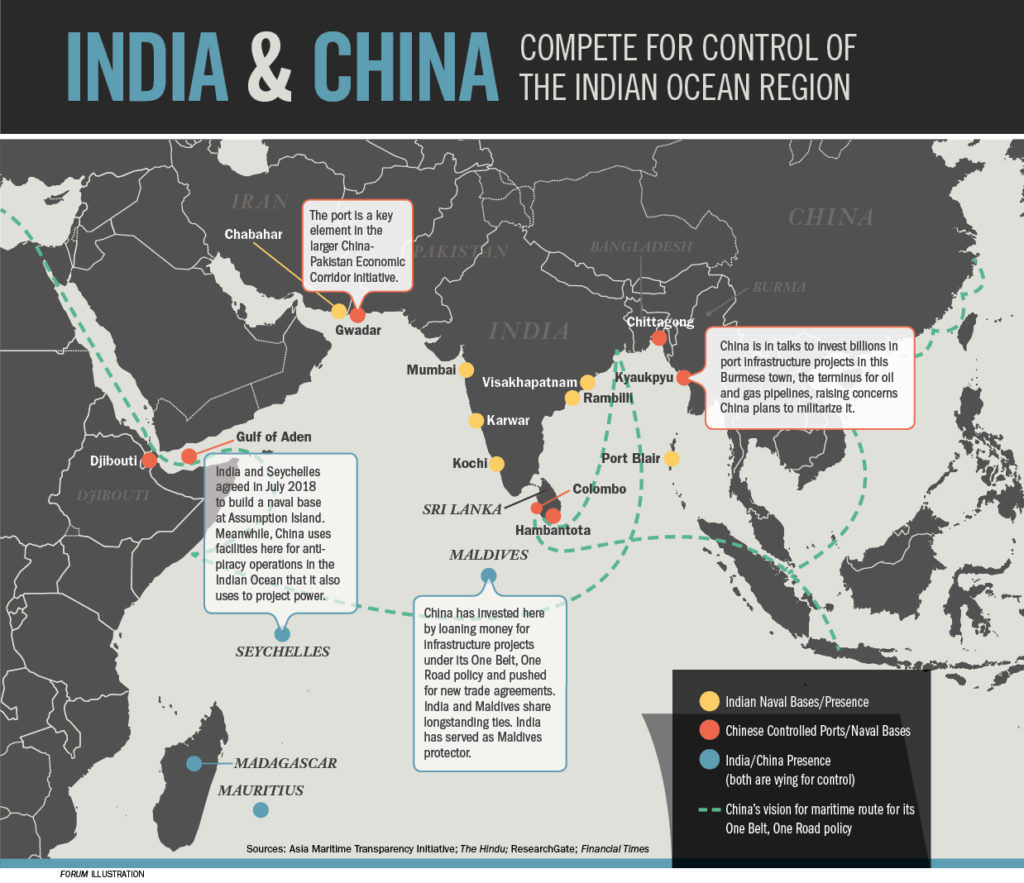

India, too, perceived the shift in its strategic environment with urgent clarity. Suddenly, Chinese forces were no longer thousands of kilometres away; they were at our very doorstep, eyeing the vulnerable Siliguri Corridor and the approaches to the Indo-Gangetic plains. The security of India’s borders became intrinsically linked to the stability of Nepal and Bhutan. Any encroachment or coercion against them would inevitably weaken India’s defences and expose its heartland. It was this realisation that prompted New Delhi to assume the role of protector, not out of expansionist ambition, but out of necessity. India’s aim was not to dominate these nations but to ensure they retained their sovereignty and remained shielded from Chinese military or political subjugation.

In Bhutan, India’s partnership intensified through defence cooperation, economic aid, and infrastructural support, ensuring Thimphu could preserve its independence while resisting Chinese pressure in unresolved border sectors. In Nepal, despite political differences and occasional friction, India continued investing in roads, hydropower projects, trade facilitation, and humanitarian aid, reinforcing the realisation that its interests aligned with Nepal’s survival as a free and sovereign state. India’s military deployments, joint exercises, and constant vigilance in the Himalayan region were never about aggression; they were about deterrence. By maintaining a credible defence posture, India prevented Beijing from exploiting these smaller nations as strategic stepping stones for force projection into South Asia.

The lesson from Tibet is clear and lasting: when a smaller nation stands alone against a determined hegemon, appeals to international morality rarely halt the advance of tanks and troops. It is only through credible security guarantees and tangible support that sovereignty can be upheld. For Nepal and Bhutan, India’s role as a security partner is not an imposition; it is the vital counterbalance that prevents the red flag from soaring over their capitals. For India, this is not just altruism; it is the realisation that the defence of the Himalayas is also the defence of India itself.

India’s concerns about China’s desire for dominance were never unfounded; they stemmed from a complex reality. In 1959, when Tibet rose and the Chinese army crushed it, tens of thousands of Tibetans fled across the mountains. I still recall old-timers of the Assam Rifles, of which I later became the Director General, discussing the initial waves of exhausted and hungry refugees, monks, traders, and families crossing into India, Bhutan, and Nepal. The Dalai Lama himself arrived in India. That moment didn’t just alter borders; it changed our perception of the passes. Suddenly, China was sitting much closer, not only politically but physically.

For India and Bhutan, our treaties stopped being polite words on paper. They became a real shield. Our military presence in Bhutan, which includes training their forces, building their roads, and setting up defences, isn’t charity; it’s necessary to protect ourselves. It was a clear message: this buffer must stay strong, and it must remain friendly to us.

Of course, even strong arrangements can cause friction. Over time, many in Nepal and Bhutan began to feel that our assistance came with conditions. Nepalese critics argued that their treaty with us was signed by the old Rana rulers, who were unpopular and out of touch, and that some clauses, such as the requirement to “consult” us on arms imports, felt like a leash. In Bhutan, some elites quietly questioned how “independent” they truly were if every diplomatic suggestion and foreign contact flowed through Delhi.

Nepal and Bhutan have remained independent for three main reasons. First, leadership. Both had rulers and governments who knew when to flex and when to stand firm. Second, geography. Bhutan’s rugged mountains and sparse population made it difficult for any invader. Isolation benefited them. Third, they played their cards wisely, maintaining decent relations with both big neighbours without leaning so heavily on one that the other felt threatened. Nepal’s approach was different. Its monarchy managed to balance India and China, keeping genuine autonomy intact. Its size, population, and diversity made any forced annexation complicated.

Ultimately, surviving in the Himalayas is about more than just defending your borders. It requires strong leadership, unity at home, favourable geography, and enough skill to be valuable to all sides without becoming so useful that someone decides to seize you before the other side does.

Sustained Buffer Statecraft: Diplomacy and Survival through the 20th Century

“The art of survival lies not in choosing sides, but in making yourself valuable to all sides.” –

The buffer state logic outlasted the British era and, in many ways, became more sophisticated. After India’s independence, both Bhutan and Nepal found themselves not only as objects of Indian geostrategic concern but also as targets of China’s ongoing ambitions.

For Bhutan, the annexation of Tibet by China (1951) and the Tibetan Uprising (1959) strengthened its alignment with India. Chinese claims over Bhutanese enclaves in Tibet faded, but the kingdom felt threatened by the Chinese military posture on the plateau. India responded by increasing economic, military, and development aid, embedding its strategic interests through infrastructure and the army support missions.

Nepal became the literal linchpin for the Himalayan strategy. The Indo-Nepalese friendship grew complicated during the Sino-Indian War of 1962, when both India and China courted Kathmandu. Although Nepal remained neutral, Indian defence strategists stayed vigilant, strengthening northern borders, constructing roads, and fostering pro-India political leadership.

Contemporary Resonance: Buffer Logic in the 21st Century

‘Nepal and Bhutan, as living embodiments of the buffer state, offer extraordinary lessons in how geography, diplomacy, and history intertwine. While treaties and protectorate arrangements once cemented their roles as protective bulwarks for greater powers, their continued survival has relied as much on native ingenuity, leadership, and luck as imperial calculation.’

Even in today’s multipolar world, the buffer state logic still lingers. China’s rise and its “Belt and Road Initiative” have added new urgency to how India and its smaller neighbours conduct diplomacy and security policy. Nepal, once again, aims to play both sides, using its buffer status to gain economic and security benefits from both Delhi and Beijing, while remaining aware of historical patterns of intervention and “guidance”.

Bhutan’s monarchy and its decision makers have proceeded cautiously, engaging steadily with both Asian giants, but have wisely avoided establishing formal diplomatic ties with China, aware that too much overture to China could disrupt the delicate balance that has maintained its sovereignty for many centuries.

Their experience reveals the paradox of buffers: to be truly useful, they must be strong and independent enough to resist being pulled into an adversary’s camp, but not so forceful as to threaten the interests of their protectors. The legacies of the 1816 Treaty of Sugauli, the 1910 Treaty of Punakha, the 1923 Nepal-Britain Treaty, and the pivotal 1949/1950 Indo-Himalayan treaties still resonate in the corridors of power in South Asia, and the lasting sense among Nepalese and Bhutanese that their fate remains, precariously and perpetually, caught between the ambitions of giants.

In this contest of geography and strategy, Nepal and Bhutan remain as much agents of their destiny as pivots of regional manoeuvre, a tribute to the enduring power and peril of the Himalayan buffer.

The Siliguri Corridor and the Sinews of National Unity

“India’s anxiety for these buffer zones is rooted in strategic hard geography. The Siliguri Corridor, only 22 kilometres wide at its narrowest, is no abstraction. It is the literal bridge between “mainland” India and the diverse, sometimes restive, Northeast.”

If adversarial powers, including now an increasingly antagonistic Bangladesh, were to try to close it, the consequences would cascade well beyond military loss; they would strike at multi-ethnic integrity, economic vitality, and national psyche.

Bhutan’s Doklam Plateau and parts of Nepal’s eastern border have gained a significance disproportionate to their size. The 2017 Doklam standoff clearly showed how even the plateau’s barren rocks and icy terrains can become the centre of a global confrontation. It rekindled fears that span from intelligence reports in South Block to the daily routines of farmers in North Bengal.

Shifting Tectonics: Strategic Challenges Post-2015

‘I’ve watched the relationships with Nepal and Bhutan shift over the years, and it’s been like adjusting your footing on uneven mountain ground, steady in places, slippery in others.’

Bhutan’s journey from protectorate to equal partner has been slow, careful, and deliberate. Since the 2007 revision of our Friendship Treaty, they have become more open to the world, even engaging in border talks with China in 2021 and again in 2023. That confidence didn’t arise by chance. Decades of building roads, dams, schools, and hospitals — much of it with Indian assistance and Indian rupees — provided them with a stronger foundation. In Bhutan, most people I have met still see India as the one steady presence maintaining their sovereignty, even as their leaders explore new diplomatic avenues.

I have experienced Nepal’s story firsthand, having served as India’s Defence Attache in Kathmandu, and I am aware of how difficult the journey has been for Nepal. The end of the monarchy, the Maoist years, the transition to a federal republic, and a form of nationalism that often depicts India as the “big brother” have changed how Kathmandu looks southward. I’ve heard the resentment in tea shops and market stalls. Yet, when the 2015 earthquake struck, it was our aircraft, medics, and engineers who arrived first, long before China. We’ve laid pipelines, built rail links, opened check-posts, and even delivered vaccines during COVID. But in 2024, Nepal still signed onto China’s Belt and Road. Clearly, Nepal was not seeking loyalty, but rather playing both sides to secure the best deal for itself.

The China Factor – Changing the Crossroads

I’ve spent enough years in these mountains to recognise when a road is simply a road and when it’s something entirely different. What China has been doing here isn’t neighbourly outreach; it’s a slow, calculated push southward. The Chinese don’t just arrive with handshakes; they come equipped with roads carved into impossible cliffs, fibre optic cables strung across passes, hydropower plants humming where silence once reigned, and loans that seem generous until you notice the strings attached.

In Nepal, they talk about the Lhasa–Kathmandu railway as if it’s a gift. I’ve walked those high passes, and to me, the Kodari highway can be turned into a ready-made corridor for tanks and troops. High-altitude roads that can transport convoys straight down to the Indo-Gangetic plains. You don’t need to be a strategist to understand the map, just a soldier who has marched on it and studied it.

Bhutan has been cautious, holding the Belt and Road initiative at bay. But the pressure never ceases. Beijing continues to push for settling its western and northern borders, which are most critical to our Siliguri Corridor, that narrow strip of land that keeps our Northeast connected to the rest of India. Lose ground there, and the map changes irreversibly. These frontiers must be guarded. This isn’t about dominating neighbours; it’s about ensuring the heartland remains secure, and that Nepal and Bhutan aren’t left isolated in the great-power games that have destabilised other nations.

Strategic Uncertainty – Doklam, the Wake-Up Call

To many, what happened in Doklam in 2017 might have looked like a small border spat. To me, it felt like the opening scene of a limited war. Chinese crews were pushing a road toward the trijunction of India, Bhutan, and Tibet. The standoff ended with the diplomats smiling for the cameras, but anyone who’s been there knows it didn’t end. The road work slowed, but it didn’t stop. The Chinese are patient; they move metres, not miles, changing the ground reality without pulling a trigger.

Doklam taught us two things: where our red lines are, and what it means to stand on them. India held its ground and did not blink. For Bhutan, it was a reminder that we won’t let them face that pressure alone.

The Economics of Crossroads: Aid, Infrastructure, and Competition

India remains, by a large margin, Bhutan’s biggest investor, donor, and economic partner. India’s development policy in Bhutan lays less emphasis on direct financial aid and more on creating a “web of dependence” that ensures both prosperity and alignment. Over 95% of Bhutan’s hydropower output, its main export, is sent to India. Indian grants and soft-loan funds have financed schools, highways, telecommunications, and even the transition to democracy.

Yet Bhutan, increasingly conscious of the risks of overdependence, has sought diversification. The 13th Five-Year Plan (2024–29) incorporates green hydrogen, digital literacy, and private sector entrepreneurship, all with Indian support, but also with Bhutanese and multilateral initiatives. Indian officials see this growth as a double-edged sword: it boosts Bhutan’s resilience, yet also expands its diplomatic choices.

Nepal: The Battle of Infrastructure and Identity

Nepal’s trade volume with India remains dominant, accounting for nearly two-thirds of recorded goods, but the past decade has seen a sharp increase in Chinese imports and investments. Today, even small Nepali towns are dotted with Chinese brand outlets, road crews, and telecom installations.

India has responded with “connectivity diplomacy”: funding railways (Jayanagar-Bardibas), petroleum pipelines (Motihari-Amlekhgunj), cross-border transmission lines, and quasi-official “Track-II” dialogues. These projects, though slower and sometimes hindered by bureaucratic delays, present a model of what Indian officials term “consent-based development”: direct negotiations, engaging local labour, and transparent data sharing.

Yet, for many Nepalis, China’s readiness to fund “shovel-ready” projects trumps drawn-out Indian processes, especially when Delhi is perceived as dragging its feet for political reasons. Indian policymakers are acutely aware that every delayed project, or whiff of high-handedness, risks pushing Nepal closer to Beijing.

The Debt Question and Soft-Power Tug-of-War

A key concern for Delhi is China’s pattern of providing credit for large projects and later using debt leverage to gain strategic concessions, a pattern observed in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port. Nepal’s cautious approach, focusing mainly on grant aid and concessional loans instead of large-scale commercial debt, is also shaped by lessons learned elsewhere.

India, emphasising grants and technical cooperation, presents its model as “mutually beneficial, non-predatory,” relying on cultural links, scholarships, Bollywood, language, and shared religious heritage to win hearts in ways megaprojects often cannot. However, digital competition is intensifying; China’s investments now encompass popular digital apps, think-tank exchanges, and social media, gradually diminishing India’s advantage among Nepali youth.

Security Webs and Unstable Borders: Joint Security and Military Assistance

India’s partnerships in the security sector remain strong for now. Bhutan’s Royal Army is still mainly trained, equipped, and (when needed) reinforced by India; annual exercises, intelligence sharing, and high-level visits ensure communication stays open during risks. Bhutan, careful to appear neutral, has never accepted a formal Indian “military base,” but in reality, it is closely integrated. Nepal’s situation is more nuanced. A history of military cooperation, with thousands of Nepalis serving in India’s Gorkha regiments, joint training, disaster response, and even counter-insurgency against Maoist rebels, has provided stability for years. However, Kathmandu’s non-aligned stance and its desire to assert complete control over its security policy mean India’s influence is maintained more through economic means and shared protocols than through direct leverage.

Borders: Contested and Incomplete

Both Bhutan and Nepal continue to negotiate their international boundaries with China, often feeling squeezed between their giant neighbours’ agendas. Recent years have seen incremental Chinese advances in “grey-zone” tactics, infrastructure expansion, “village-building,” and ambiguous patrol lines. Indian intelligence agencies regard such moves as designed not only to shift ground realities but to send a message: Beijing is ever-present, and only Delhi stands between the status quo and a new Himalayan order.

Politically, Bhutan has maintained a delicate balance, discreetly negotiating with China over boundary issues while consistently consulting with Indian officials. Nepal has occasionally appeared more inclined to play both sides, minimising or dismissing reports of Chinese encroachments in the Humla and Dolakha regions. At the same time, louder protests are raised over often minor Indian activities on its southern border.

Domestic Shifts: Nationalism, Identity, and the Limits of Leverage

Much of India’s difficulty can be traced to Nepal’s vibrant but unstable politics: multi-party jockeying, ideological shifts, and an undercurrent of identity politics rooted in ethnic and regional diversity. The rise of the Madhesi issue, with Indian-origin communities in Nepal’s southern Terai feeling marginalised by Kathmandu, has created complex new challenges. Blockades, citizenship disputes, and sporadic violence serve as reminders that even open borders can become flashpoints rather than bridges. Indian overtures to Madhesi leaders have sometimes strengthened these sentiments but also increased resentments among “hill-centric” Nepali elites in Kathmandu, thus fueling anti-India sentiment.

Bhutan: Managing Change, Preserving Stability

Bhutan’s social fabric remains tightly woven, guided by the principle of Gross National Happiness and a culture wary of both Indian and Chinese advances. However, as young people grow more restless, seeking education, migration opportunities, and greater digital connectivity, Indian engagement at the grassroots level becomes increasingly important. From digital scholarships to volunteering in disaster relief, India must act with sensitivity, respecting Bhutanese pride while striving to surpass Chinese “economic diplomacy.”

Green Power – A Different Kind of Race

Bhutan’s rivers have already lit many of our towns back home, and new projects in the east and south aim to strengthen our economies even further. Nepal has a similar resource in its waters, holding enough potential to transform its fortunes if the deals are fair and the transmission lines actually cross the border.

However, Chinese teams in sharp suits offer terms that sound more appealing than ours. They speak of exporting Nepal’s power north into Tibet and beyond, turning rivers into instruments of influence. It’s not as dramatic as a road leading to a border post, but make no mistake, the race for green energy is its own battlefield. And in the long run, it could shape these mountains even more than the roads or railways we have fought over.

Digital, Cultural, and Soft-Power Frontiers

In both countries, the competition for future influence is increasingly digital. India’s new initiatives in digital cooperation, scholarships, start-up funding, and cross-border e-governance platforms aim to attract the under-40 demographic, who will be shaping policy tomorrow. Chinese firms, for their part, offer free devices, online commerce opportunities, and innovative city designs, often operating ahead of local regulatory capacity.

Media, film, sports, and joint festivals all pour oil on the waters when diplomacy grows tense. Both Bhutan and Nepal continue to send thousands of students to Indian universities, still see Bollywood as a lingua franca, and depend on Indian journalists and think tanks for much of their global engagement. However, social media, often vulnerable to nationalist manipulation, can ignite conflicts with alarming speed.

Regionalism and Multilateral Diplomacy

India’s response has been to reinforce regional institutions such as SAARC, BIMSTEC, and BBIN, where consensus, collaborative infrastructure, and people-to-people contacts create redundancy and “lock-in” to pro-Indian orientations. Delhi’s approach is subtle: foster a sense of shared ownership, distribute benefits across social groups, and diminish the appeal of China-led bilateral deals.

The Road Ahead: Strategies for a Precarious Future

The upcoming decade will challenge India’s Himalayan leadership like never before. Success will depend not only on money, soldiers, or agreements, but also on India’s ability for patient cooperation and prudent restraint.

In Bhutan, India’s challenge will be to support modernisation and sovereignty without ever allowing strategic priorities to seem more important than local ownership; to strengthen an alliance of equals, not a master and dependent relationship.

In Nepal, India must navigate complexity with empathy, respecting Kathmandu’s desire to hedge, being receptive to trilateral initiatives with China when suitable, and basing relations on youth, culture, and economic ties, not solely on old military links.

Trauma, Cooperation, and the Power of Example

The earthquake that devastated Nepal in 2015 served as a test for regional cooperation: Indian military and disaster relief efforts crossed the border, reinforcing India’s image as a first responder. However, the aftermath—marked by politicised aid, reconstruction disputes, and heated rhetoric—showed that even well-meaning actions, if poorly managed, can have negative consequences. The lesson? Humility and a focus on local priorities should guide even the most well-intentioned strategies.

Coping with the Unexpected

The region is characterised by Himalayan unpredictability, earthquakes, coups, sudden border crises, and youth movements that go viral. In such volatility, a “whole-of-society” approach, leveraging universities, religious organisations, private companies, and media, provides India with its strongest safeguard.

Conclusion: The Steward of High Places

Ultimately, India’s “strategic interests” in Nepal and Bhutan cannot be reduced to a contest of fences, funds, or flags. These are living relationships, shaped as much by stories, memories, and aspirations as by treaties or balance sheets. The actual test of Indian statecraft will be in keeping the Himalayan crossroads open, breathing, and secure, so that, whether in crisis or opportunity, the “roof of the world” remains a place of shared hope, not division.

In these high places, where the storms of history meet the calm of the snows, India’s future will be determined not by how strongly it holds its neighbours, but by how effectively it helps them stand tall together.

Author Brief Bio: Lt Gen Shokin Chauhan, PVSM, AVSM, YSM, SM and VSM, was the Chairman of the Cease Fire Monitoring Group, Nagaland and North East India in August 2018. He was the Director General of Assam Rifles, India’s oldest and largest Para Military Force. He has had held several key appointments during his long career in the Army. He has served at the Apex level in the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Home Counter Insurgency, Counter Terrorism, Border Guarding and Human Resource Management. He also has vast experience in military diplomacy since he was the Defence Attaché in the Indian Embassy in Nepal for three and half years (2004- 07). A strong business development professional, Gen Chauhan holds a PhD in International Relations and Defence Studies from the Panjab University, Chandigarh.

References

- “Bhutan’s Unique Position in India’s Regional Strategy.” Indian Express, March 3, 2025. https://indianexpress.com/article/upsc-current-affairs/upsc-essentials/bhutans-unique-position-in-indias-regional-strategy-9861627/

- Centre for Social and Economic Progress. “Crossroads of Power: Strategic Aspects of India’s Economic Relations with Neighbours to the North-East.” CSEP Working Paper, 2024.

- Kaul, Nitasha. “Beyond India and China: Bhutan as a Small State in International Relations.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 22, no. 2 (2022): 297-325.

- “India-Bhutan Relations | Current Affairs.” April 15, 2024.

- Johny, E. “Foreign policy strategies of Nepal between China and India.” International Politics (2024).

- “The Collapse of India’s Himalayan Buffer: Chinese Interference in Nepal and Bhutan.” Indian Defence Research Wing, July 24, 2025.

- Inner Call. “India’s Unique Bonds with its Himalayan Brothers.” August 8, 2025.

- “Perspective: Indian Diplomacy in 2024.” January 3, 2025.

- Thapa, M. “Geopolitical rivalry between India and China in Nepal.” JSDP Journal 3, no. 1 (February 2025): 111-129.

- Joshi, S. “India, Nepal Love-Hate Relationship.” Ummid.com, May 25, 2025.

- “India-Bhutan Development Cooperation Talks.” July 1, 2025.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. “Bhutan Development Cooperation Talks (June 30, 2025).” Press Release.

- Kim, J. “India on One Side, China on the Other: Small-State Security in the Himalayas.” United States Institute of Peace, Jan 8, 2025.

- “How Nepal and Bhutan Navigate the India-China Rivalry.” Intellinews, May 28, 2025.

- “China’s Influence in India’s Neighbourhood is Growing Fast.” The Print, Feb 11, 2025.

- “India-Bhutan relations: Current Affairs.” Jan 22, 2025.

- Sanyal, D. “Indo-Nepal Relations are Ever Expanding, says South Block Official.” Rising Nepal Daily, July 4, 2025.

- “View of Foreign Policy of Nepal: Strategic Approach to the Changing World Order.” Unity Journal, Sept 10, 2024.

- Bank, Andrzej. “The Role of Regional Powers in Ensuring Security and Stability in South Asia.” Polish Political Science Review (2024).

- Sood, Rakesh. “India, China, and the Himalayan Battlelines.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 2024.

- Maskey, Ritu Raj. “Border Security and Strategic Challenges in the Indian Himalayas.” Asian Affairs, Jan 2025.

- Habib, Haroon. “Increasing Indian Influence in Bhutan: Opportunities and Challenges.” Journal of International Affairs, 2025.

- Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. “India–Nepal Relations.” Bilateral Brief, March 2025.

- “India is Losing South Asia to China.” Council on Foreign Relations, May 28, 2025.

- BBC Monitoring. “Bhutan cautious as China eyes disputed border region,” April 2025.

[23]

[23]